The South African

The South African

The desert campaign

By the end of July 1941, we had received and sorted our new equipment, were joined by the rest of the 1 st Field Regiment, South African Artillery, and were almost immediately moved to El Alamein, 120km west of Alexandria, to a site located within a kilometre of the sea. There was no tented village here. Instead, we were introduced to the general principle of dispersing vehicles and digging ourselves into the ground. Lt Woodrow McGibbon and I shared a dugout lined with sandbags and covered by a small two-man tent.

At El Alamein, the newly arrived regiment set about accustomising itself to the realities of war in the desert. Intensive training with new equipr:nent, sentry duty at listening posts on the beach at night to warn against enemy landings, adjusting to water and food rationing, all this was the order of the day. There were a few diversions - bathing parties in the sea once a week and, less attractive, assisting with the digging of the El Alamein defences, a backbreaking task in the hard, rock-strewn sand. It was during this early period in the desert that we witnessed a huge pall of smoke on the seaward horizon. Some sort of transport vessel had met its end, we thought. In fact, we had witnessed the sinking of the newly commissioned British battleship, HMS Barham, by a submarine at a time when enemy actions had virtually neutralised British dominance in the Mediterranean Sea.

Calibration of 25-pounder guns by South African gunners in the desert

(Photo: By courtesy. South African National Museum of Military History)>

In early 1941, the situation in North Africa had changed. On the side of the Axis powers, there was a new formation - the Deutsche Afrika Korps (DAK). At its heart were the 15th and 21st Panzer (Armoured) divisions and the 90th Motorised Infantry Division. Under the aggressive leadership of General Erwin Rommel, the Allied forces were driven eastwards, back through Libya to the Egyptian border. By 15 April 1941, the line was held at Buq Buq-Sofafi and a lull set in while the two opposing forces reorganised.

Return to the frontline

In late November 1941, three subalterns, including myself, were attending a course at the Artillery School at Almaza, close to Cairo. The course ended and we heard the news of considerable fighting taking place some 350km to the west. In one swift counter-attack by Rommel's forces, then in retreat, they had virtually annihilated the 5th South African Brigade at Sidi Rezegh. Convinced that our regiment must have been involved in the general operations, the three of us were anxious to re-join our comrades as soon as possible. Hopeful and in high spirits, we set off for the Cairo railway station where we were certain that the Railway Transport Officer would be able to direct us to our regiment's present location. Eventually pinning him down in a seething mass of civilians and soldiers, we were disappointed to find that he had never heard of the regiment and thus had no idea about their location. Nonetheless, he gave us three tickets for the next train bound for the western terminal, Mersa Matruh, on the Egyptian coast.

We boarded the crowded train without any idea of our next move and, by mid-morning, were steaming westward. At 21.00, in absolute darkness, we reached our journey's end. Together with five other soldiers, we alighted and were met by an officer with a feeble torch. He led us, stumbling, down a tortuous path to what he termed 'a rest camp', fed us, and provided an empty tent and a lantern. Bidding us a good night, he remarked, 'Take it easy, stay as long as you like. There's no hurry.'

On the following morning, we pressed him for information on how to find our regiment. He advised us to walk a kilometre into what remained of Mersa Matruh, find the rear headquarters of the British 8th Army, and make some enquiries there. This we did. Amongst the rubble and the few buildings still standing, we came across an unoccupied office, open to the road, with a large map festooned with a myriad of little coloured flags. This must be it, we thought, and examined the map closely until an irate major stormed in and delivered a severe reprimand, threatening to have us arrested as spies. After convincing him of our intentions, he offered to send a signal requesting the position of our regiment. Hopeful, I asked when we could expect a reply, thinking, in my naivety, that it might take an hour or so. 'Well,' he replied, 'it could take up to a week.' Not good enough, we thought. We thanked him for his help and, with tongue in cheek, said that we would call back.

Crestfallen, we trudged back along the dusty road, past the 'rest camp', to the railway station. There, we found an individual in very casual dress who seemed to know all about the comings and goings of the local trains - the station master. Explaining our dilemma, we asked if he knew of any way by which we might reach the front lines. 'Sure', he replied, 'Take a ride to railhead. They know everything there.' When we asked how to get there, he responded, 'Well now, if you can be back here before 09.00 tomorrow, I might be able to squeeze you into a freight train. It's illegal, of course, and, mind you, it will be uncomfortable. It's just a single home-made track through the desert, no food, no water, and [pause] no guarantee. Hot as hell!' Railhead, he went on to explain, was a distribution point of military equipment to the fighting troops, with all manner of transport moving continuously to and from the battle zone.

A typical distribution point in the desert, where black South African drivers

brought truckloads of supplies for distribution to frontline units.

(Photo: SA National Museum of Military History).

Needless to say, the following day found us clanking our way slowly over the low escarpment in a dusty, wooden goods railway truck. The sun set over an endless sea of rocks and sand and we continued at a slow pace. At about midnight, we awoke to find the train stationary in an eerie stillness. On climbing out of the truck, we found another stationary train alongside and, in the bright moonlight we could see a mass of something spread over the desert some distance away. The drone of a lone aircraft sent us scuttling away from the train to settle into some soft sand for the rest of the night. No air raid followed.

The station master had been true to his word. As morning broke, we found a huge sprawl of tents, huts and acres of equipment, and plenty of vehicular movement. A day after our arrival, we found a captain who agreed to transport us as far as Sidi Omar. His small convoy of Bren gun carriers set off through the featureless terrain, trailing clouds of choking dust. Navigation was by compass and by looking out for the numbered 44 gallon drums set in the desert for this purpose. We passed through a gap in the stout barbed wire fence which stretched from the coast in the north near Fort Capuzzo to the horizon in the south and served as the border between Egypt and Cyrenaica. During this trip, I learned from the driver that the main opposition forces were locked in battle to the west and that, in their retreat, the Axis forces had left some strong points - Bardia, Sollum and Halfaya Pass - to harass the Allied supply lines.

At Sidi Omar, not far from the border fence, we pondered our next move, still without any idea of the whereabouts of our regiment. A dot on the map, amongst dozens of other dots, Sidi Omar was a mess, the scene of a savage conflict two days earlier. The debris of war lay strewn about. There were crumbling slit trenches, shell holes, burnt out and overturned vehicles, and steel helmets, their owners now buried in shallow graves. Strangely, we took heart from this dismal scene, for it made us feel closer to our goal. Quite unexpectedly, we found out how close to our goal we really were - on the outer edge of this destruction was a gathering of 3-ton trucks and a handful of men, amongst whom stood our Regimental Quartermaster. We learned that the 1st Field Regiment was part of an investing force, located on the western perimeter of Bardia, and, sadly, that Capt Wakefield, 2nd Battery, had been killed by inadvertently driving towards an enemy machine-gun post while searching for a water point. As the regiment's first casualty, the news of his tragic death was indeed a great shock.

Bardia

On the following morning, 17 December 1941, we set off on a 40km ride in the 3-ton trucks, with black drivers, carrying mail and supplies to the regimental headquarters. The small convoy must have been spotted by the enemy in the Bardia Fortress for we were welcomed by a sudden shower of about ten deadly shells bursting across our zig-zag path. Until then, I had only seen the enemy as passive prisoners of war, sweeping paths in the Cairo area. Now, he was out there, somewhere, deliberately aiming and hurling missiles at us. There was no damage done and we arrived at our respective battery positions later that afternoon. The 2nd Battery's guns were neatly tucked away in a wadi and had just concluded a sharp duel with the enemy. The smell of dust and cordite still hung in the air and hot shell cases lay around the gun positions. The sky clouded over and a light rain began to fall. During a skirmish in the afternoon, one of our signallers was pinned down by enemy fire while repairing cable. Any puff of wind flapping a piece of his clothing drew unwanted attention to him - and a burst of machinegun fire. It was not until after dark that we were able to extricate him, unharmed but very wet and shaken.

As the cold winter days passed with occasional rain, one became accustomed to the desultory shelling by each side, and the rattle of machine-gun fire. It was a holding game while, unbeknown to us, larger actions were being planned. Christmas Day 1941 dawned with an overcast sky and was celebrated with a lunch boasting slightly more than the stock diet of bully beef or 'spam' and biscuits. The Regimental Quartermaster had risen to the occasion and provided extra tinned potatoes, some small Christmas puddings, and an extra supply of beer. In the cooler weather, there was an added treat - the tinned margarine had managed not to separate. We were inventive. Someone had found a trestle table and another enterprising soul had attempted to decorate it using a handful of local vegetation stuffed into an empty shell case.

Artillery button

A few days later, we received orders to relinquish our wadi hideout to another unit, and to move to a new position south-east of Bardia. A determined effort to take Bardia was planned for 1 January 1942. To this end, a large force was congregated on the south and south-east sectors. At 01.00, a signaller and I went forward in bitterly cold drizzle to establish a forward observation post close to the enemy defence line. An hour later, a well-planned artillery barrage commenced and continued at pre-determined intervals until 03.30. The enemy response was immediate and, through the rain squalls, we watched as all hell broke loose. The velvet blackness was splashed with sheets of flame and clouds of orange smoke as vehicles exploded and burnt. Against this fiery background, tracer ammunition, like long strings of pearls, streaked back and forth across the sky. This pyrotechnic display was accompanied by the clamour of bursting shells, gunfire and machine-gun clatter. At 04.00, the main tank and infantry attack was launched and the noise was deafening.

By midday, the sky had cleared and the first objectives had been reached and secured. A minor dust storm blanketed the area and the scene quietened. More rain fell later in the afternoon during a redeployment in preparation for the next attack, planned for 22.00 that night. Another night marked by whining shells, smoke and flame passed slowly and diminished as the dawn broke. At 09,00 on 2 January, General Schmitt, the German Fortress Commander at Bardia, surrendered unconditionally to General I P de Villiers, commander of the 2nd South African Division. The battle for Bardia was over.

Point 207

Other German strongholds continued to threaten our lines of communication. On 4 January 1942, we were on the move again, heading south into the desert to eliminate the enemy at Point 207, a mere dot on the map. After a quiet two weeks without any serious effort on our part, the fort capitulated. What I remember most about this episode was the experience of being engulfed in a sandstorm that approached silently from the east as a huge wall of swirling stand. It was about 100m high and slowly blocked out the sun, bathing the desert in orange-tinted light. I felt the sharp sting of flying sand and pebbles and started to choke as the fine, powdery dust found its way into my nose and throat. As

the guns and vehicles vanished from sight, I cowered in my dugout with a wet handkerchief over my face. For roughly an hour, I had an alarming feeling of self-asphyxiation

as breathing became very difficult. Sand-storms, I learned later, lent another dimension to the progress of battles in the desert as contesting tanks, shrouded in thick dust, would often pass each other unwittingly.

Artillery flash

48 hours

After the capture of Point 207, we proceeded eastwards down the rugged Halfaya Pass, through Sollum to a site on the coast for a stay of rest and recuperation. Our rugged 'resort' reminded me very much of the Natal South Coast, with sea-washed rocks and a stretch of typical coastal vegetation, a very welcome change from the starkness of the desert. At leisure, we settled in, bathing and cleaning up our equipment. A great silence fell over the desert and the only sounds were the gentle splash of surf and the distant rumble of military transport on the coast road as the British 8th Army continued its advance into the west. Our rest period was short-lived, however.

Rommel's withdrawal had ended 560km to the west, near to his supply depot at Tripoli. With his forces replenished, he turned and pushed eastwards forcefully. The Allied forces, with their overextended supply lines, were soon in full retreat and suffering heavy losses. At its seaside 'resort', our regiment remained blissfully unaware of this turn of events for 48 . hours. Then it received orders to pack up and hurry back to the front line. Refuelled and fully stocked with ammunition, the column joined the coast road, where progress was hampered by long columns of miscellaneous vehicles, mainly air force personnel and their equipment, trundling back from abandoned air fields in the forward areas. 'Give them hell, boys, and good luck', they yelled as we passed, and 'You dunno what you're in for. . .' (using more expressive vocabulary, of course).

South African servicemen 'up North' enjoy a welcome dip into

the cool waters of the Mediterranean Sea. (Photo: SANMMH).

The Gazala Line

Our new destination was yet another dot on the map, Tmimi, where the 1st South African Brigade was assembled and in urgent need of artillery support. After a 250km journey, we joined the brigade at 21.00. Then it was decided that the Tmimi position was untenable in the face of the Axis advance, so the entire brigade made an extraordinary night move in bright moonlight across the desert to Ain el Gazala, about 32km to the east. About halfway to our new destination, I was detailed to take up a position straddling a desert track, with two guns and a company of infantry. Our purpose was to pick up any stragglers and to delay the enemy advance at all costs to allow the main body sufficient time to occupy the new positions. Fortunately, the enemy slowed its advance and we were pulled back to the new line early the next morning. During our brief watch, a sentry brought in a lone Indian soldier, immaculately dressed, who had escaped from capture and had been walking back through the night in the hope of finding the Allied lines. Several Free French Brigade escapees also passed through our patrol.

The new line of defence, known as the 'Gazala Line', was hurriedly designed as a series of fortified 'boxes' stretching about 80km southwards from the coast, ending at the fortified well, Bir Hakeim. The small port of Tobruk, lying some 80km to the east, was the largest 'box' in the defensive triangle into which the British 8th Army then poured as much armour and other reinforcements as could be mustered. The defence of Tobruk was in the hands of the 2nd South African Division, together with some other Allied units. The northern half of the 'Gazala Line' was manned by the 1 st South African Division, and the remainder by various British and Free French brigades.

We took up our assigned positions and hastily dug gun and vehicle pits using picks and shovels, the engineers blasting hard rock where necessary. After establishing forward observation posts and registering the guns on prominent features, we settled down to await the Axis onslaught, but the desert ahead remained silent. Having learnt his lesson about overextending his supply lines, Rommel had halted at Tmimi.

A search-and-destroy venture

During the two-month lull that followed, both sides played cat-and-mouse, probing into no-man's land with small, armed reconnaissance groups. I was part of a search-and-destroy venture that set out with four guns, a company of infantry, . and two anti-aircraft guns. At 04.00, on a cold morning, led by an engineer, we wound our way slowly and cautiously through a broad minefield - a very unnerving experience - until we were let loose into the open desert. After spending an hour or two wandering through wadis, with no sign of the enemy, we stopped for a break. When a lone fighter ripped past some distance away, disappearing over a crest, the men felt sure 'it must have been one of ours', but were wrong. A few minutes later, the same aircraft was spotted flying low, travelling very fast and heading directly for our column, machine-guns blazing. Bullets clattered as we ducked for cover, shouting and cursing. Seconds later, the attack was over and the aircraft disappeared again, but an armour-piercing bullet had penetrated the breach block of one of the guns, rendering it unsafe for further use. Then we were instructed to open fire. The response was immediate, about seven shellbursts splattering around our gun position. One splinter was very familiar - part of a '25-pounder' shell, the type of ammunition we were using. Was the enemy using captured guns or was this a sign of something even more serious? It soon transpired that another Allied column, to our south, had failed to display the agreed signals and had failed to respond

to ours, causing our column to engage them. Fortunately, there were no casualties and no damage during this embarrassing 'close shave'.

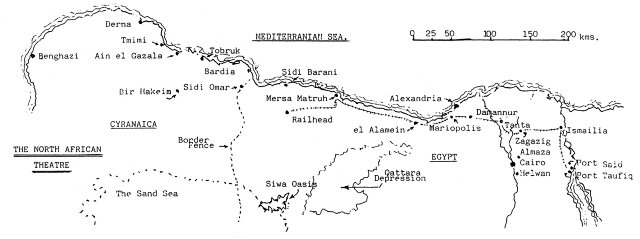

The author's hand-drawn map of the North African theatre of operations as he experienced it in 1941-2.

The enemy remained scarce and, late in the afternoon, we started our return journey. With the sun fading, it was a race to find and negotiate the minefield before dark. Perhaps the lead vehicle strayed from the path, for, about halfway through the minefield, there was a sudden loud thump. A gun-towing vehicle, known as a 'quad', struck a mine and was damaged, its driver suffering minor head injuries. This incident brought the column to a halt and we had to spend the night in the middle of the minefield, not permitted to leave our vehicles. We sat nervously through the darkness and, with the approach of dawn, our apprehension increased - we could be 'sitting ducks' to enemy aircraft prowling the skies. An hour later, we were rescued by a group of engineers. All in all, it had not been a productive operation.

A 'Quad' gun porte pulls a 25-pounder gun and limber

through rough desert terrain (Photo: SANMMH).

Outflanked

In April 1942, Rommel made his move. The Axis forces began to flex their muscles, making their presence felt by intermittent bombing attacks and shell-fire. Our forward observation post was situated on the forward slope of a low rock-strewn hillock overlooking a long, wide wadi. In front, our infantry occupied their slit trenches and, shimmering through the hot air, at a distance of about 1 DOOm, one could just discern the outlines of the enemy forward positions at the far end of the wadi. One day, while on duty at the post, I heard a rumbling noise coming towards the dugout. Stepping outside, I came face to face with a large, unexploded shell gently rolling down among the stones. I froze as it bumped its way down to come to rest against the rock wall of the observation post. Somewhat shaken, I explained the situation to the signallers and that night we covered it ever so gently with sandbags.

In another incident at this post, we once observed a large Italian aircraft circling slowly above us before descending to land 200m ahead of our infantry lines on the flat surface of the wadi. At first, nothing happened. Then, Lt Maughan-Brown, who was nearby, raced down in his Y2-ton truck and took into captivity several high-ranking Italian officers, along with important documents intended for the German Command. The aircraft was subsequently destroyed by gunfire.

At 04.00 on 6 April 1942, an enemy artillery barrage opened the first deliberate attack on our sector. As the sun rose, enemy infantry started the long advance up the wadi towards our front line and we initially held back, practising the old army adage, 'wait until you can see the whites of their eyes'. Then, suddenly, there was rifle fire, machine-gun fire, mortar fire, all pouring into the advancing men to devastating effect. Under the withering fire, the Germans fell to the ground, scraping and clutching about for any available cover. Any attempt to continue the attack was met by renewed fire and they were pinned down for most of the day, many offering themselves as prisoners. Our men suffered only limited casualties, but we knew then that a major battle was imminent.

Artillery cap badge

As it turned out, this skirmish was clearly a diversion to mask a much more sinister move by Rommel. A couple of days later, while continuing to apply pressure to the northern sectors of the Gazala Line by increased bombing and shelling, he directed his powerful 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions, with supporting troops, down south towards Bir Hakeim. Other ranks in the British 8th Army were in awe of Rommel at the time; the rapidity and destructive force of his return along the coast road from El Agheila had created so strong an impression of a leader with supernatural abilities, that the Allied High Command had issued instructions that Rommel was an ordinary person like anyone else.

During this period of intensified air and ground activity, Lt McGibbon and I, in our gun position, heard the usual drone of aircraft in a clear blue sky. Glancing up instinctively, we located a formation of nine Stukas moving slowly in a wide arc ahead of us. Stukas were slow-moving but highly efficient divebombers, to be taken very seriously when flying in one's air space. They slowly turned and when almost above us, rolled into a graceful dive. At first, my gun partner and I stood there, rivetted to the spot. Then, we saw the bombs leave the belly of the leading aircraft and I heard McGibbon shout, 'My God! They're coming straight for us!' Diving onto the dusty floor of our dugout, tin hats on our heads, we heard the scream of the bombs as the earth reverberated around us. Sand trickled down in little rivulets between the sandbags and my portable 'Zenith' radio jumped about with every thunderous explosion during the attack. Afterwards, we leapt out into a great blanket of swirling dust and smoke. We could hear the repetitive bark of the Bofors anti-aircraft guns. It was hard to imagine that anything might be left intact, but, to our surprise, the damage was minimal. A bomb splinter of jagged metal had ripped through our tent cover and into our van, dug-in nearby. Men and guns were unharmed, but a 44 gallon drum, filled with water and used to dampen the dust in front of the guns, had disappeared entirely and the ground was pock-marked with craters. Four times during the course of the afternoon, our gun positions were attacked again, but casualties remained light. One transport vehicle was destroyed and Sergeant-Major White, in charge of the battery transport, was killed. After one of the raids, when the Stukas slowly climbed away towards the sea, chased by the tracer shells from the Bofors guns, we were gratified to see two of the aircraft fall into the sea, trailing plumes of smoke.

By May 1942, Rommel had succeeded in outflanking the Gazala Line in the south, bypassing Bir Hakeim and sweeping in great numbers up into the heart of the Gazala-Tobruk-Bir Hakeim triangle. This area, 'Knightsbridge', was held by a Guards Brigade with much armour. A fierce and prolonged tank battle developed in the area, which came to be known as the 'Cauldron'. Fortunes shifted. At one point, the 8th Army appeared to be succeeding, but failed to accept the challenge, so the battle was lost and the Allies then had to deal with a fighting withdrawal all the way back into Egypt. The gravity of the situation became apparent to us only when we were told that the 'boxes' forming the Gazala Line had been sealed off and that each would have to fend for itself. Rommel's forces were marauding deep behind us in the triangle. The only protection afforded to the coast road, the 'Via Balbia', which was our lifeline to the east, was the escarpment with few navigable passes down its rugged slopes. While we still faced some harassing fire to the west, there was no serious threat from this direction.

A South African gun position in the North African desert. (Photo: SANMMH).

Tobruk

At midday on 11 June 1942, the 1st Field Regiment was suddenly ordered to prepare for withdrawal from the 'Gazala Line'. The afternoon was spent in a frenzied rush to destroy all excess material and, by dusk, we commenced the treacherous descent down the 'Serpentine Pass' onto the coast road, pushed forward by some sporadic shelling by the enemy, but with no casualties or damage. We arrived at Tobruk at dawn on 12 June. Then, to our dismay, 2nd Battery was detached from the regiment and placed under command of the 25th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, while the remainder of our regiment moved through Tobruk and scampered back into Egypt with remnants of the 8th Army . The reassignment of 2nd Battery was to boost the thin artillery support in the Tobruk garrison. Under orders, we took up a designated position in the south-easterly area in close support of two infantry units, the 2/5th Mahrattas and, on their left flank, the 2/7th Gurkhas. The 2nd Cameron Highlanders held a position to the right of the Mahrattas.

The gun pits provided were in a bad state of repair. In fact, the whole site was an open piece of desert, dominated by a single high feature, known as 'Dummy Railhead', which lay outside the perimeter and was already in the hands of the German forces.

Retreat from the Gazala Line. Military transport hastens eastwards

to avoid encirclement by Rommel's Afrika Korps advance.

(Photo: SA National Museum of Military History).

The situation did not look good, but when our battery commander, Major Morris, reported his dissatisfaction at a battery commanders' conference, he was considered a pessimist. As subalterns were seldom presented with all the facts, we assumed that we were in for another 'Tobruk Siege', as had occurred 'the year before. With this idea in mind, I wrote and proposed to my sweetheart, Solveig. The letter must have caught the last post; three days later, Tobruk Fortress was sealed off by the Axis forces.

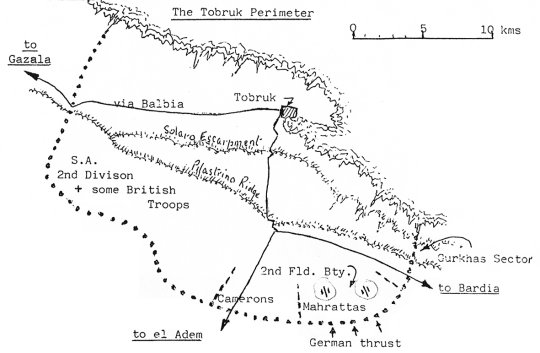

This hand-drawn map by H A Candy shows the desperate situation

faced by the 2nd Field Battery as a result of the German penetration

of the south-east perimeter of the Tobruk defences.

On the afternoon of 18 June, I was to take part in a planned raid from the perimeter as gunnery officer with two guns and back-up troops. My gun partner, Lt McGibbon, very anxious to take part in the exercise, persuaded me to trade places with him. As a result, two signallers and I laid a telephone line later in the afternoon and occupied an advance observation post located just behind the Gurkha sector. After supper, we settled down to routine night watches. The night was very quiet and I heard a distant noise beyond the Mahratta lines. As the hours passed, the noise became discernible-the clanking and screeching of tracked vehicles on the move. This information was repeatedly reported to battery headquarters. The noise ceased shortly after 02.00 and an ominous silence settled over the desert.

At dawn on that fateful morning of 19 June 1942, 2nd Battery forward observation posts close to the Mahratta line spotted enemy infantry alighting from carrier vehicles and, in response, ordered the battery to open fire. These were the first shots fired in this battle for Tobruk. Within seconds, Rommel's forces replied and the Mahratta front exploded under a massive enemy artillery barrage, soon joined by showers of bombs from their air force, based only a few kilometres away at El Adem. With our own airfields out of range, we were deprived of air support.

About 4km away on my right flank, where, only the day before, we had enjoyed a clear view of my battery, there was now only a huge, swirling cloud of dust and smoke. The few signals received from the battery indicated that it was under heavy attack by advancing German tanks and infantry, which had already overwhelmed the Mahrattas. Lt McGibbon and his driver, Gunner How, had been killed, and the battery commander, Major Morris, and a troop commander, Capt Hancox, were seriously wounded. At about 22.00, we finally lost contact with battery headquarters and reported to the 25th Field Regiment, to which our battery had been seconded. We were instructed to remain at the post and to report any enemy activity on the Gurkha sector which lay spread out ahead of us. This front was absolutely quiet. Later in the morning, I watched as several Bren gun carriers left the sector and disappeared into the cloud of dust and smoke moving steadily towards the edge of the escarpment, about 8km behind us.

As the afternoon dragged on, I became disheartened, increasingly convinced that the Gurkhas and the three of us in my observation post were isolated. The sun set over a relatively quiet landscape; the noise of battle growing distant. Columns of black smoke rose from points around the harbour. We spent a restless night, wondering what lay in store for us the next day. On 21 June, dawn broke with the clatter of tracked vehicles and the distant sound of gunfire. We heard footsteps approaching from the direction of the Gurkha sector and, thinking that this was someone coming over to seek information or to give a message, I stepped out to meet him. He was no Gurkha, however. Instead, I came face to face with a German soldier, who thrust the muzzle of his machine pistol in my face. He was trembling and very nervous and burst into a tirade of German, unintelligible to me, but his gesticulations were clear - discard your arms and place your hands on your heads. I had expected that I might be wounded or killed in action, but had never considered that I might be taken prisoner.

A spectacular view of the harbour town of Tobruk, scene of a defensive battle that ended disastrously

for the South Africans on 21 June 1942. (Photo: SA National Museum of Military History).

We were marched out of the wadi, a number of German soldiers evident on the higher ground. We arrived at a rudimentary Axis headquarters, swarming with jubilant German and Italian soldiers. We became more despondent when we were joined by Gurkha soldiers. Each prisoner was allowed to find a greatcoat, a blanket and a waterbottle and then we were marched off under armed guard. Our route took us past bomb craters, shell holes, burnt-out and broken vehicles, and many newly-filled graves. Close by, a battle was still raging - the last stand of the 2nd Cameron Highlanders, who held out until dusk that day. As we descended from the edge of the escarpment, the coastal plain stretched out below us, strewn with more debris. A great pall of smoke hung over the little town of Tobruk. Most depressing of all was the sight of the roughly erected barbed wire enclosure accommodating thousands of khaki-clad men, huddled under any bits of material they could find as shelter from the torrid midday sun. En route to join them, we were greeted by a grinning German tank commander, leaning from his high turret, his mop of bright ginger hair shining in the sunlight, who commented, 'For you, the war is over'.

I wondered whether there were any survivors from my battery, which had taken the full brunt of Rommel's vicious attack on the previous day. After the war, I learned that he had employed his crack units, the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions and the 90th Motorised Infantry Division, during his assault on Tobruk, determined to succeed where he had failed a year earlier. Released into the temporary 'cage', I wandered among the despondent men, finally locating a group of men and officers from my unit. The eight guns of 2nd Battery, 1st Field Regiment, South African Artillery had, been the first to engage the enemy during this fateful battle and, at the battle's end, our two remaining guns were the last in action.

Acknowledgements

The editor would like to thank, firstly, Mrs Candy for granting permission for the publication of her late husband's material, and secondly, Prof Mike Laing of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, for making all the necessary arrangements in this regard.

Readers may be interested to know that Henry Arthur Candy's participation in the battle of Tobruk is mentioned in J A I AgarHamilton and LC F Turner, Crisis in the Desert, May-July 1942 (Oxford University Press, London, 1952):

On p 179: 'The preliminary bombing wrecked communications in the sector of the attack and even the Headquarters of the Mahratta battalion had difficulty in learning what was going on. Much of the information came from the Forward Observation Officer [Lt H A Candy] of the 2nd South African Field Battery who was watching the German penetration through field-glasses, and after 1000 hours, when the commander of the Mahrattas destroyed his wireless set, the artillery observation post was the only source of information ... '

On p 216: 'Two units, cut off from the rest of the [Tobruk] Fortress, continued to resist: the Gurkhas among the precipitous wadis where the eastern perimeter meets the coast, and the Camerons just east of the El Adem road block ... (A Forward Observation Officer of 2nd Field Battery who had been cut off in the Gurkha area, but was still uncaptured, remembers an excited voice ringing up in Nepalese and broken English, calling for the fire of guns which had been in enemy hands since the previous noon) ... '

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org