The South African

The South African

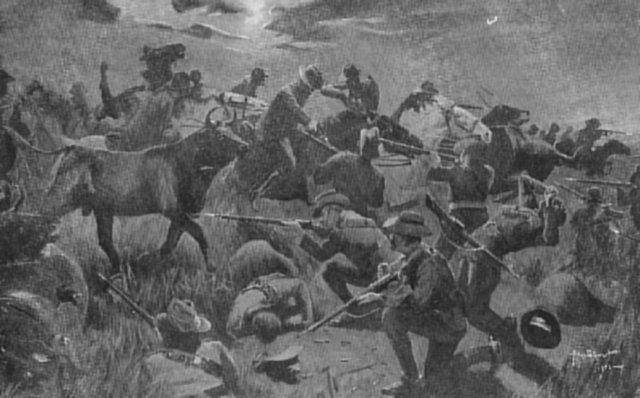

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles in action at Holspruit

(from Wilson,After Pretoria)

On the farm, 'Langverwacht', some thirty kilometres south of Vrede, stands the ruined monument to the 23 men of the 7th New Zealand Mounted Rifles who were killed nearby on the night of 23 February 1902. They had been part of a British column engaged in sweeping the area so as to flush out the Boer commandos operating in that region. Their quarry had been Boer General Christiaan de Wet, who had eluded capture for more than two years. He was not to be captured on this night either as his commandos punched a hole in the British line and disappeared into the night.

Guerilla warfare - The challenge

By early 1902, the Anglo-Boer War was coming to an end but very far from over. Faced with the highly mobile Boer commandos and their guerilla tactics, the British had evolved new technologies which were taking a serious toll on their adversaries. The eastern Transvaal had virtually been cleared of its population and Louis Botha's men had mostly withdrawn to the hills around Vryheid. In the western Transvaal, Koos de la Rey still fell on British columns and convoys whenever an opportunity arose. Jan Smuts was in the north-west Cape, tying down numbers of British troops around O'Kiep. Hertzog and Malan and others operated in the eastern and northern Cape, defying every effort to surround and capture them.

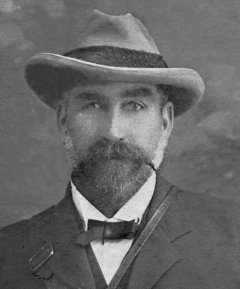

Boer guerilla leader, General C R de Wet

(Photo: SANMMH).

It was in the Free State where the most successful Boer guerilla leader, Christiaan de Wet, operated. De Wet may be said to have been the first to advocate and demonstrate the hit-and-run Boer guerilla strategy that the British at first found very difficult to counter. That de Wet remained at large was an astounding feat since he was always in the thick of the fighting and many times had been very close to a point of capture. His principal tactic was that of surprise and when he managed to surprise his enemies he was invariably successful.

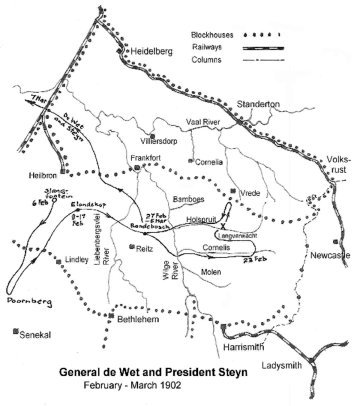

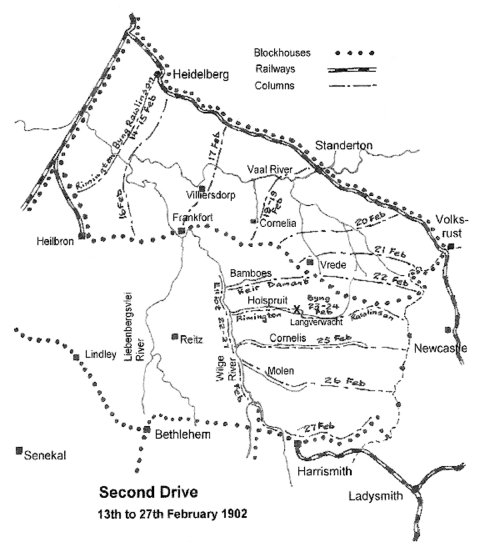

Area of operations of General de Wet and President Steyn

February - March 1902.

To protect the railways, the British built small stone forts or blockhouses at strategic points along the railway lines. These were usually two storeys high and had a garrison of thirty men under a sergeant. They were proof against artillery but took long to build, about three months, and were very expensive to construct, costing between £800 and £1 000 each. As the number of Boer attacks on the railways increased, it became clear that something cheaper and more quickly and easily erected was needed. Major Spring Rice of the Royal Engineers, then in Middelburg, devised a blockhouse made of two concentric cylinders of corrugated iron filled with shingle which was effective at least against rifle bullets and cost a mere £16 to erect. By June 1901, lines of these small forts extended along the railway lines and a start was made on cross-country lines which were to serve as barriers to the free movement of the Boer commandos, who were now to be driven and cornered against them. (The blockhouse system is the subject of a complete chapter in Leo Amery [ed], The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol V, 1907, pp 396-412. See also Richard Tomlinson, 'Britain's Last Castles' in the Military History Journal, Vol 10 No 6, December 1997).

At first, British strategy was to raid the Boer laagers at dawn. To do this, they needed good intelligence of Boer whereabouts and highly mobile columns which could cover long distances at night so as to surprise the Boers at daybreak. De Wet and President Marthinus Steyn with the Free State Government had a number of hiding places in the north-eastern area of the Free State, centred on the small village of Reitz, with heliograph communications from some of the prominent hilltops in the area. Thus, they were able to concentrate their forces when necessary and scatter if a large British force appeared. Places frequented by them in the Reitz area were de Wet's Own farm, 'Blijdschap', and Slabbert's farm, 'Rondebosch'. The ailing Free State president was able to rest at 'Rondebosch' for some weeks and busy himself with the business and correspondence of government.

Early in February 1902, a new system of sweeping was attempted. Before then, the Boers had been able to pass through the British lines when night fell and gaps in the line opened up as the troops bivouacked. With the blockhouse lines now complete and reinforced for the occasion of a drive, British mounted troops were able to form a continuous line, 90km in length. The flanks of the line would be on a blockhouse line and the horsemen were able to maintain that line by riding straight ahead by day. At night, every officer and man would assume picket duty in a continuous entrenched line of pickets. In theory, there would be no gaps in the net and every Boer commando would be hedged in by the line of horsemen, the blockhouses with their wire entanglements and armoured trains operating on the railway lines. To maintain such a line over broken country with hills and rivers to be crossed required discipline and skill, not to mention endurance, since the drives covered fifteen to twenty kilometres per day for a week or more. (A detailed description of the new system is provided in Amery, 1907, pp 467-73; Col M F Rimington's orders are detailed on pp 476-7).

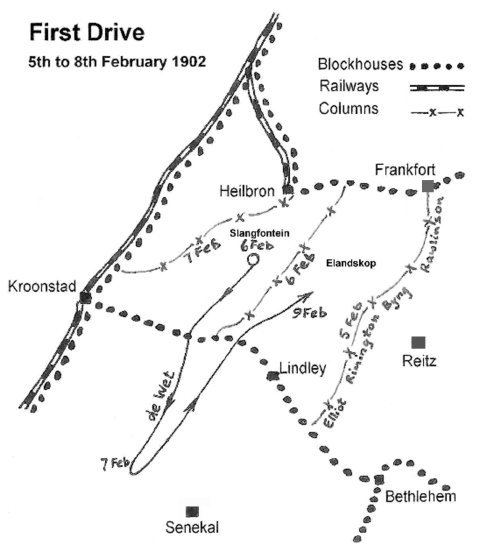

De Wet's whereabouts needed to be established before a decision could be made by the British as to the direction of the first attempt at the new model drive. His base near Elandskop (today the village of Petrus Steyn), was well-known but every attempt to capture him there had thus far failed. Colonel Julian Byng camped at Fannie's Home on a bluff overlooking the Liebenberg's Vlei River early in February 1902. Lt-Col Garatt's column was dispatched to Roodekraal and Armstrong Drift on the Liebenberg's Vlei River, where they came across the rearguard of a Boer force under Commandant Walter Mears on 3 February. Mears had been ordered to bring the guns, captured by de Wet at Groenkop on Christmas Day 1901, across the blockhouse line between Lindley and Bethlehem. Garratt's men included the 7th New Zealand Mounted Rifles (NZMR) who had 'a hard gallop and a running fight of some miles' and succeeded in routing the Boer rearguard and recapturing the lost guns. Major Bauchop, commander of the 7th NZMR, received a personal telegram from Lord Kitchener, while Lt-Col Garratt 'gratified the New Zealanders by assuring them that it was one of the best mounted charges he had ever seen'. The guns would have been valuable to the Boers had they had the opportunity to use them. (There are numerous accounts of this action, but it is impossible to establish exactly where the clash took place. See, for example, J Lourens and J A J Lourens, Te na aan ons hart, pp 49-52; Amery [ed], The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol V, p 475; Christiaan de Wet, Three Years War; and New Zealanders in the Anglo-Boer War [online] for various descriptions).

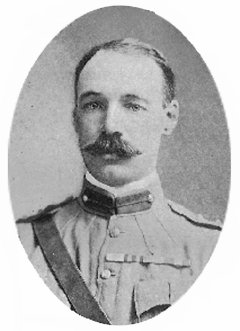

Lt Col F S Garratt

With intelligence that de Wet was in the vicinity of Elandskop, the British line was formed along the Liebenberg's Vlei River in a line that stretched for 90km. The sweep to the west as far as the main railway line was detected by de Wet's scouts and he moved south with his force of 700 men who had joined him at Slangfontein. Managing to avoid the advancing British line on the night of 6 February, de Wet and his men crossed the Kroonstad-Lindley blockhouse line on the farm, 'Doornkloof', heading for the Doornberg, north-west of Senekal. The British swept westwards and, on the following night, closed off the area between America Siding on the main line and Heilbron. Several hundred Boers were known to be within the cordon and every possible means was used to ensure their capture. Some managed to cut their way out, but nearly 300 were killed, wounded or captured.

First Drive

5th to 8th February 1902.

Lt Edward Gordon of the Royal Scots Fusiliers wrote in his diary of the last night of the drive: 'Firing almost continuous all night. There were undoubtedly a number of Boers trying the line at various places all along to find good places for breaking thro[ugh]. About eight armoured trains could be counted on the main line and the Heilbron branch line, by their searchlights going all night. It was a wonderful sight, like a great display of fireworks with the beams of searchlights flashing all over the sky and a continual roar of rifle fire, punctuated by the rattle of a Maxim or the report of a field gun. It was about the most wonderful night I've ever spent and didn't sleep a wink all night.' (Unpublished diary now in the possession of Lt Gordon's son, Major Antony Gordon).

The first drive had failed to capture their principal target. A second, conducted on a much larger scale, was then planned. A segment of the Transvaal that lay to the south of the Natal railway line was identified as the initial target. According to the plan, the line would then wheel right and sweep down through the north-eastern Free State between the Wilge River and the Drakensberg. It would involve the use of almost 30 000 troops and take nearly two weeks to complete. De Wet, hearing that the coast was clear, had returned to Elandskop, crossing the blockhouse line once again. This time, however, he encountered enemy fire and lost two killed and eight wounded. In preparation for the planned second drive, Maj-Gen Elliot reached Lindley on 16 February, making for the Wilge River where his men were to form the line along the river. Receiving intelligence of de Wet's whereabouts near Elandskop, he sent a column under Lt-Col de Lisle to capture him, but, once again, de Wet was nowhere to be found.

The following day, de Wet rode eastwards and joined the Free State Government at 'Rondebosch'. President Steyn had remained there, well outside the limits of the first drive. For once, however, de Wet's intelligence was faulty and, on the approach of Elliot from the west, he made the decision to cross the Wilge River and break through the British line somewhere near the Drakensberg. With the approach of Elliot's men, it was clear that President Steyn and the Government would have to follow. Government documents were hidden in a cave not far from 'Rondebosch', together with de Wet's clothing and some ammunition. (Today, this 'cave' is well-known locally - a hollow within what was once an overhang. Hundreds or thousands of years ago the shelf fell down and access to the hollow is through and over the rubble caused by the rockfall).

Commandant Manie Botha (SANMMH)

On the night of 22 February, de Wet and his men reached the Cornelis River and Commandant Manie Botha and his Vrede Commando joined them. Botha told them of the British force sweeping in a line from the Wilge to the Drakensberg. They were thus in danger of being trapped against the Bethlehem-Harrismith blockhouse line. The British sweep caused a wide variety of people to flee and join up with de Wet and his commandos.

Commandant J A Alberts (SANMMH)

Commandant Alexander Ross

Amongst them were two Boer commandants, Alexander Ross and his men from Frankfort and Hendrik Alberts and some men from Heidelberg, as well as significant numbers of people and their animals who had left their farms and were fleeing southwards. On 23 February, the crowd followed the commandos as they moved along the left bank of the Cornelis River. By late afternoon, they had arrived at the farm 'Brakfontein' to the south of the Witkoppe. De Wet had intended to skirt the Witkoppe to the east and travel north up the valley to Strydplaas, but his scouts told him that the British held a strong position at the head of the valley. (The name of the farm 'Brakfontein' was changed some years later to 'Blijdskap', presumably in recognition of de Wet's short visit on that day).

Second Drive

13th to 27th February 1902.

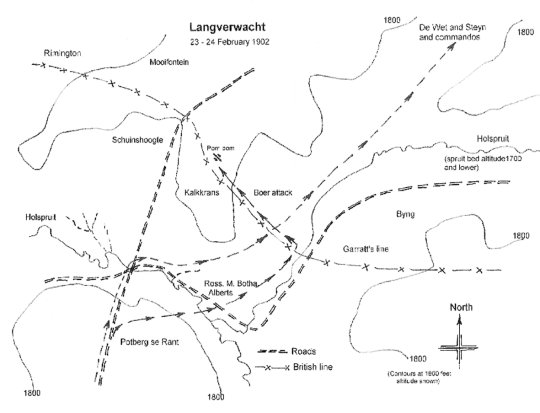

Unable to delay until the next morning, de Wet resolved to break through the British line at Kalkkloof. Col Michael Rimington's line stretched from Pramkop, which practically overlooked the Wilge River, to Mooifontein, where it joined up with Col Julian Byng. The rolling grassland from Vrede southwards enabled the columns to maintain their line with little difficulty. The line swept easily over the low hills of the Bothasberg, but the Kalkkloof provided more of an obstacle. The left of Byng's line, formed by the 7th New Zealand Mounted Rifles, filed down across the valley of the Holspruit and reformed their line along the crest of the next section of high ground to the south, on the farm 'Langverwacht'. To join up with the left of Rimington's line, Lt-Col Cox's 3rd New South Wales Mounted Rifles, Byng had to stretch his line up a kloof leading to the farm 'Mooifontein' towards Rimington's line, which was north of the Holspruit. At the head of the kloof, Captain A R G Begbie, Royal Garrison Artillery, placed a pom-pom gun in a small, quickly erected redoubt of stones.

Col Michael Rimington

Col J H G Byng

The Boer scouts, noticing this kink in the line, assumed that there was a gap, but there was none. The New Zealanders were entrenched in pickets of six men except where the line crossed the Holspruit. Like all the rivers and streams in this vicinity, this stream, with its high banks, constitutes a natural barrier to the easy passage of horses and vehicles.

The Boer multitude left Brakfontein after dark and retraced their steps of that afternoon along the valley of the Cornelis River, the commandos leading the way, followed by the crowd of carts and spiders and the herds of cattle and horses. They arrived at the Holspruit at midnight. De Wet and Steyn and his mule wagon crossed the river at a ford where there is a bridge today. The three commandos, constituting a force of about 700 men, mostly veterans, skirted the road to the east and moved towards what they supposed would be an undefended portion of the line. They advanced in two groups, one quietly up the bed of the Holspruit.

The New Zealanders, having heard the noise caused by the Boer multitude for some time, were alert. Sentries had heard the 'lowing of cattle, the rumbling of wagons and the voices of women' and had roused the men who had been asleep after a good meal of roast mutton. The Boers in the donga, the bed of the Holspruit, managed to get in behind the line while the rest of the force rushed one of the pickets. Of the six men in the trench, five were killed. Ross and Manie Botha and their men turned left and advanced along the line of trenches in a half-circle. The New Zealanders were concerned about hitting their own men if they fired along the trench line, but, under fire from all sides, soon put up a stout resistance. 'The fire was something terrific. Bullets! They were just like hail stones falling on cabbage leaves' was how Trooper Lytton Ditely later described the skirmish, while in hospital in Harrismith where he had been taken after the fight.

Sergeant Minifie of the 7th New Zealand Mounted Rifles was stationed with the pom-pom and had run out of ammunition but heard that a new case of ammunition was coming up. He rallied his men and managed to hold on for about another fifteen minutes. The pom-pom fired twenty or more rounds before becoming jammed. Captain Begbie was killed and, to prevent the gun from being captured by the approaching Boers, Minifie and his men managed to run it down the hill where it ended up in a small ravine. The further advance of the Boers up the kloof and onto the high ground of the farm, 'Mooifontein', was stopped by the 3rd New South Wales Mounted Rifles. Colonel C F Cox 'fought like a tiger' and had formed a line across the head of the kloof with four pickets. No medals were awarded for this action but Kitchener's chief of staff, Lt-Gen Ian Hamilton, wrote to Lord Roberts on 27 February to say that 'the New Zealanders, who are about our best men ... did not belie their reputation on this occasion.' (For accounts of the action, see Amery [ed], The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol V, pp 489-90; Christiaan de Wet, Three Years War; New Zealanders in the Anglo Boer War [online]; Chamberlain and Drooglever, The War with Johnny Boer, which includes an extract from Major G K Ansell's staff diary of Rimington's column and letters from members of Cox's 3rd NSWMR; Andre Wessels, Lord Roberts and the war in South Africa, 1899-1902, provides the full text of Hamilton's letter to Lord Roberts; J G Kestell, Through Shot and Flame, contests versions that contend that the Boer attack took place behind a large herd of cattle).

De Wet tried to encourage all his men to charge the line and resorted to his sjambok to persuade the slackers to move forward. Many of them fled, probably because of the unexpected resistance. A gap had been created in the line and this enabled many of the fighting men to get through with some of the cattle and horses. They rushed along the flat ground on the right bank of the Holspruit and up a valley which brought them to safety and onto the high ground. De Wet and Steyn were with them and the two men in charge of de Wet's little wagon also managed to get through. They headed for the Bothasberg and spent the night on the farm, 'Bavaria'. Here, a wounded member of President Steyn's bodyguard died as well as a young boy named Olivier. The next day, they returned to the site of the fight to find that the British had departed after burying the Boer dead.

Twenty-three New Zealanders were killed in the action and a further 44 were wounded, most hailing from Canterbury and Otago on South Island. They were buried in a mass grave on 'Langverwacht' farm and in 1903 a monument was erected on the burial site. (The monument remained intact until 2003 when a nearby oak tree, evidently planted at the time that the monument was built, collapsed after a grass fire, demolishing the stone column and damaging the marble plaque with the names of the fallen. The author hopes that the memorial will be restored as it forms an important link with the events of that night in 1902). Captain A R G Begbie of the Royal Garrison Artillery was one of those killed, so too Bombardier J Ryan. Three men serving with Col Cox were apparently wounded, but there is no record of them in the casualty roll. Boer casualties were also high. De Wet admits to having lost eleven dead and twelve wounded, but the Boer practice of carrying away their dead could mean that more were killed.

The monument at Langverwacht, as it appeared in 2000.

The damaged monument at Langverwacht, 2006

Langverwacht

23-24 February 1902.

Only three days after the action at 'Langverwacht' nearly 600 Boers under Commandant Jan Meyer surrendered to the Imperial Light Horse, part of Colonel Sir Henry Rawlinson's column, on the farm 'Strathnairn' in the Harrismith district. 'Langverwacht' was thus the last engagement of any consequence in this part of the Free State. De Wet and President Steyn, who had become seriously ill, managed to break through the blockhouse lines in their path and cross the Vaal River to meet up with Koos de la Rey. (According to Meintjies, President Steyn, p 172, the President was suffering ataxia or lack of control of the limbs, caused by some kind of neurological disorder, and de la Rey's respected doctor, von Rennenkampf, was unable to give much relief). Lacking the inspired leadership of de Wet, the commandos remaining in that part of the Free State could do little more than evade capture in the last three months of the war.

Col Sir Henry Rawlinson

Apart from the memorial at 'Langverwacht', there are two places in New Zealand where the men who took part are remembered. Farrier Leonard Retter was from Johnsonville, now a suburb of Wellington on North Island. His father was a blacksmith with two other sons in the New Zealand contingents during the Anglo-Boer War. A monument to Retter stands in Moorefield Road in Johnsonville and a short distance away are memorial gates at the entrance to the public park. In Amberley, which remains a small village north of the city of Christchurch on South Island, there is a monument to Farrier Sergeant O H Turner with the inscription: 'To thine own self be true'. These words had been written on a piece of paper found on Turner's body. No monument to the Boers exists at 'Langverwacht', but, according to Willem L E Naude, Maar doodkry is min, pp146, 153, 155, the names of members of the Vrede Commando who died there - and elswhere - are inscribed on a memorial in the Vrede Dutch Reformed Church Garden.

De Wet and President Steyn left 'Rondebosch' on 5 March 1902, heading northwards to the western Transvaal. De Wet's mule cart was abandoned at a farm, presumably Gen Wessel Wessel's 'Lovedale', and his personal effects and government papers remained hidden. On 4 March, Elliot's column started on a sweep northwards on both sides of the Wilge River. Major Charlie Ross and his Canadian Scouts held one portion of the line and stumbled upon the cave to unearth '310 000 rounds of small-arm ammunition, several hundred shells for field artillery, ... three sets of field signaling apparatus, all this from under the feet of a British garrison of long standing' (Amery, Vol V, p 476). Two weeks previously, on 22 February, the South African Light Horse from Elliot's column guarding the Wilge River had skirmished along Rus-se-Spruit without finding the cave. Ross also found de Wet's embroidered sash of office, now in the possession of author Neil Speed in Australia. In his book, de Wet explains that, on his journey northwards, 'I had only the clothes that I was then wearing. I would have sent for another suit had I not heard that the enemy were encamped close to the cave where our treasures lay hidden.' (De Wet, p307; Lourens and Lourens, pp 54-59 [for detail of the action along Rus-se-Spruit]; Neil Speed, Born to Fight, pp 126-30, concerning the discovery of the cave ).

The entrance to the de Wet cave on General Wessel Wessel's farm.

Sources

Amery, L S (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Volume V (Sampson Low, Marsten and Co, London, 1907).

Chamberlain, Max, and Drooglever, Robin, The War with Johnny Boer (Australian Military History Publications, Loftus, Australia, 2003).

De Wet, Christiaan, Three Years War (Archibald Constable and Co, London, 1902).

Gordon, Lieutenant E I D, 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, unpublished diary.

Hall, DO W, The New Zealanders in South Africa 1899-1902 (War History Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1949).

Kestell, J D, Through Shot and Flame (Methuen and Co, London, 1903).

Lourens, J, and Lourens, J A J, Te na aan ons hart (Privately published, Reitz, Free State, 2002).

Meintjies, Johannes, President Steyn (Nasionale Boekhandel, Cape Town, 1969).

Naude, Willem L E, Maar doodkry is min (Privately published, Vrede, Free State, 2001).

Speed, Neil, Born to Fight (The Caps and Flints Press, Melbourne, 2002).

The South African War Casualty Roll (J B Hayward & Son, Polstead, Suffolk, 1982, reprint of War Office document of 1902).

Wessels, Andre (ed), Lord Roberts and the War in South Africa 1899-1902 (Sutton Publishing Ltd, Stroud, Gloucestershire, 2000, for the Army Records Society).

www.nzrh.org.nz (New Zealanders in the Anglo-Boer War).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org