The South African

The South African

A deadly German V1 flying bomb, launched in occupied territory

makes its way towards Britain. (Photo: SANMMH ).)

The war between England and Germany broke out in September 1939, but the invasion of Holland, Belgium and France only started on 10 May 1940. Holland had hoped to be able to stay out of the war (as she had managed to do in the First World War, 1914-1918), but the German dictator, Adolf Hitler, had other plans. I was 12 years old at the time and remember that tenth day of May 1940 very well. It was a beautiful Spring morning and I stood on the balcony of our house in Rijswijk, a municipality adjoining The Hague, and watched German paratroopers descending from the sky.

The Occupation

As the invading Germans approached from above, they were being shot at by Dutch ground forces. My father, 42, had wanted to join the Dutch Army by registering at a local school, but had been turned away for being too old. Even walking in the streets was becoming dangerous. Shots were being heard everywhere and I should not even have been on that balcony.

The Dutch Royal Family lived in The Hague and paratroopers landed in the palace gardens. Because Prince Bernhard, Princess Juliana's husband, was German by birth, the Nazis had hoped to break the spirit of the Dutch nation by taking Queen Wilhelmina prisoner. However, they had miscalculated. Prince Bernhard proudly stood by his wife and mother-in-law. It is said that he used armed force to get them and himself out of the palace and into a car to flee to the Hoek of Holland, where a British destroyer was waiting to take them to England. It was a hazardous journey. A furious Hitler shouted during one of his public ravings: 'Das Oranien Weib sol kein Residenz haben' (The bitch of Orange [i.e. the Queen] shall have no residence').

To the Germans' surprise, the Dutch armed forces put up a fierce resistance. By 14 May, the Germans had advanced no further than central Netherlands, so they decided to force the issue. They bombed Rotterdam, an open city, as they had done previously to Warsaw, Poland. A large section of Rotterdam was laid waste and many civilians lost their lives. The German command then issued an ultimatum to the Dutch - surrender or the cities of Utrecht, Amsterdam and The Hague would suffer the same fate. The Dutch cabinet had no option but to capitulate and, on 15 May 1940, Holland became a defeated and occupied country. An Austrian, Seys Inquard, was made Governor-General of the Netherlands and, shortly afterwards, gave his maiden speech in the parliamentary buildings in The Hague.

The mood of the Dutch was one of 'wait and see'. During that first year of occupation, while the situation at the war front was still in their favour, the German approach to the Dutch was, on the whole, polite and correct. Persecution of the Jewish population had yet to begin in earnest. During the first year, many Dutch were ambivalent in their thinking. What if the Germans should win the war? The Dutch Nazi Party (the NSB), gained prominence. They had been in existence before 1940, but had never amounted to much, their members often being of mediocre ability. The German defeat at Stalingrad and the turning of the tide in North Africa began to change things for the worse in Holland.

The Jews

After that first year, the German noose began to tighten, particularly for the Jews. They were soon being hounded from place to place. They were barred from using trams, trains, or buses and from entering cinemas. The machinery for transporting them to concentration camps, and later the gas chambers, sprang into action. My piano teacher disappeared this way and there was very little we could do about it. We would have gone the same way ourselves. Later, in 1944, my parents managed to help a semi-Jewish family to retain their apartment.

The Underground

As time went by, the Dutch Underground Movement became better organised and the expression of antiGerman feelings in the Netherlands increased. There were terrible acts of revenge on the part of the Nazis. In the village of Putten, for example, the entire male population was shot to pay for the murder of a German commander. By the end of 1942, the Germans had started to anticipate a possible Allied invasion of the Atlantic or North Sea coastline. As a result, the entire coastline, from Denmark down to the Spanish border, became a fortress. Several large cities are located along this coast, not least of which is The Hague, which had a population of 500 000. In 1943, a third of The Hague - the section bordering the coast - was separated from the rest of the city by the construction of canals. The residents were told to evacuate, houses were boarded up and some houses even razed to the ground to create shooting corridors. Residents had to share accommodation in other parts of the city, or leave altogether. My school had to move premises twice, not very conducive to learning. In the same building, there was one school in the morning and another in the afternoon.

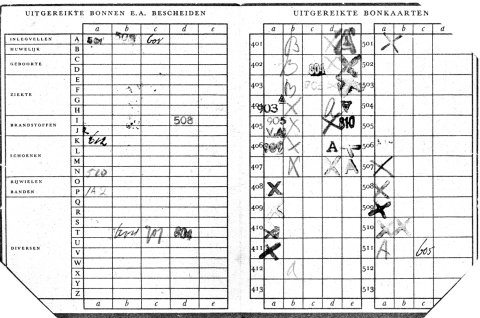

The author's wartime food and clothing ration card, now in the Archives

of the South African National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg.

Royal Dutch Shell Company

My father was an employee of the Royal Dutch Shell Company. Because of the company's dual nationality, there were, at that time, two head offices, one in the Hague and the other in London. The Germans, without an oil industry of their own, coveted the Dutch oil expertise, which had its roots in the then Dutch East Indies. Fortunately, the German war

machine never reached the oil-rich Baku in the southern Soviet Union. If it had managed to do so, I shudder to think what would have happened to us as a family. What I do know is that, on 10 May 1940, all Shell documents, secret and otherwise, were dumped in haste in the swimming pool of the Shell sports club in Rijswijk.

Nazi influence

Nazi influence in Dutch broadcasting grew by the day. Nobody was allowed to perform in the studios, or in public, unless they belonged to the so-called 'cultural chamber'. As the news from the battle front became more and more embarrassing for the Germans, so the format of the bulletins started to change. The bulletins began with five minutes of march music to set the mood, followed by five minutes of news, punctuated with expressions such as 'a victorious retreat', and concluding with another five minutes of march music. Although food was not plentiful and its distribution was strictly controlled, there was still enough to survive. By 1943, the distribution of food was such that most people were guaranteed a slim body, a huge contrast to today's high incidence of obesity.

The Allies invade

By September 1943, the situation in Holland had begun to change rapidly for the worse. The Allied invasion of Normandy had taken place and Allied forces were steadily progressing northwards. By the time they reached Belgium, part of the German front appeared to have collapsed and the Allies liberated Belgium within a week. They entered the southern Netherlands and advanced as far as the Rhine River, at Arnhem. This is where, in September 1944, disaster struck and thousands of Allied paratroopers perished. The Allies had halted here for several days to consolidate their forces, apparently unaware that, north of the river, the Germans were retreating. These few days cost the Allies dearly. When they eventually attacked, the Germans had regrouped and Montgomery was defeated on that front. He then turned his troops eastwards, towards Germany, leaving the whole of western and northern Holland at the mercy of the Nazis. Heavy fighting around Arnhem and at the bridge of 'A bridge too far' fame saw the civilian population crawling at night from garden to garden in attempts to get out of the line of fire.

Meanwhile, north of the river and in the big Dutch cities, the Nazis and their Dutch collaborators panicked and bolted for the railway stations in an attempt to catch a train east to Germany. Rumours were rife that the Allies were now in Rotterdam and would reach The Hague within an hour. This day in September 1944 is referred to in Dutch history as 'mad Tuesday'. Shortly after that, the Dutch railways went on strike in protest to German action and remained on strike until the end of the war. By then, every night, the sky over Holland reverberated heavily with the noise of hundreds of Allied bombers on their way to Germany. Their mission was to destroy the German cities and infrastructure. For Holland, this resulted in the theft, by the Nazis, of Dutch rolling stock, lock, stock and barrel, sometimes without even altering the destination boards. I remember going on holiday in Holland in 1946, travelling in a cattle truck.

A family of horseless civilians pull their caravan through a town in wartime Holland

(Photo: SANMMH).

No food

With no transportation system available to the Dutch people, food became extremely scarce. Central kitchens were erected in the cities at strategic points, allowing each person a meal a day in exchange for a special sticky sweet coupon. By January 1945, this meal consisted of nothing more than a plate of sugar beet soup, plus the weekly supply of a small black loaf of bread. Naturally, this was totally insufficient to sustain life and many people either became ill or died. Those still able went on frequent trips, by bicycle (sometimes fitted with wooden tyres), into the countryside to barter with farmers for food in exchange for cutlery, linen, or whatever else they had. Money had no value and life was down to basics. There was no electricity, no public transport, no shops, offices, schools, radio or telephone service. Water, important for sanitation, was available only for two hours a day.

Into hiding

One morning in November 1944, because so many Dutch males were idle at home, the Germans ordered all men between 17 and 45 years of age to gather at selected street corners in the cities at a certain hour, with a winter coat or blanket. They were to be picked up and transported (in my case, by barge) to work camps in Germany. I remember the trucks driving

around and the announcements being made by megaphone. Failing to report would result in severe punishment. Having just turned 17, I was eligible for the order. My father, who fell outside the order on a slim margin, had already anticipated the order in 1943 and had added a trapdoor to the floor of our ground floor lounge. A large, heavy carpet and a very heavy table went over this trapdoor. The space underneath the floor was probably no more than half a metre high and then there was sand. After hearing the announcement, I was told to get under the floorboards and into the pitch darkness and, an hour later, a German soldier arrived for an inspection and to search the house. He noticed music sheets on our piano and my mother, quite fluent in German, engaged him in conversation. In all fairness, it must be mentioned that not all Germans were Nazis. They all had to join the Hitler Youth and had been conscripted into the army. They were victims of the Nazi creed, whether they realised it or not. The soldier who entered our house no doubt had a family in Germany and knew that every night his country was heavily bombed. From my hiding place, I could hear every word that was said, just above my head. After a while, he left and I became illegal.

My parents kept me under the floorboards for another two hours, in case the German soldiers came back. In the meantime, however, the Dutch Resistance had alerted their counterparts in the United Kingdom as to what was happening on the Dutch west coast. Suddenly, British aircraft came swooping down low over the roofs of our suburb. Their aim was to sink the transport barges that were waiting in a canal nearby. Crouching there in the dark, I thought my last hour had arrived. I had to get out to see that the world was not collapsing on top of me. Later, though illegal, I was able to move around, but had to be very careful of roadblocks.

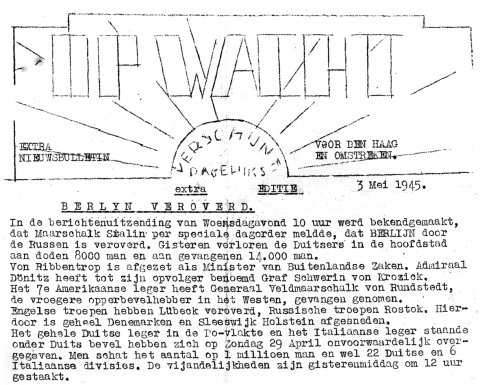

'Op Wacht' newsletter of 5 May 1945, reporting the news that Berlin had fallen.

(This newsletter is one of several donated by the author to the Archives

of the SANMMH in Johannesburg in 2006).

Brave women

With so many men out of the way, the burden of foraging for extra food fell mostly on the women. Once a fortnight, my mother used to go by bicycle, with two women friends, to an acquaintance of ours, who had a cheese farm near Gouda, some 50km away. She would be gone for two days and return with bottles of milk, cheese and butter packed on the carrier at the back of the bicycle and strapped into bags to the side. However, by December 1944 and with no end to the war in sight, my mother took a desperate step. She decided to cycle all the way to the northern province of Friesland, a distance of some 250km. It was a hazardous trip in mid-winter, necessitating.having to sleep in ditches or porticos. It was known that the Friesland farms had food, but there was no transport there. Halfway along the route, at the town of Zwolle, there was a bridge over the Ijssel River, patrolled by the Germans. They would allow people through on the way up, but, on the return, they would confiscate half their food. My mother made it all the way to Friesland to a little village called Balk, where a farmer and his wife took her in. They made a small cart on wheels for her, to be attached to her bicycle, and filled it with lard, cooking oil and grain. Then she was ready for the trip home.

It was well known that barges regularly sailed with basic food kitchens from Friesland to the cities of western Holland across the Ijsselmeer (the old Zuiderzee). My mother talked a skipper into giving her space on board his barge and, in this way, managed to bypass the notorious bridge at Zwolle. She sailed all the way to Amsterdam and then, via canals, to The Hague, arriving in Rijswijk early on Christmas morning, 1944. My dad and I had not heard from her for an entire month and the reunion was one of great joy, a real Christmas experience! My mother was exhausted and emotionally drained. When the war ended in May 1945, she spent three months in a sanatorium.

V1 Rockets

In November 1944, the Germans began launching the infamous 'doodle bug' or V1 Rocket, a flying rocket with wings, from the Dutch west coast, with targets in the United Kingdom. The launching of these contraptions required a runway and the small aerodrome of Iepenburg was ideally suited for this purpose. The first V1 roared over our house one night, leaving us wondering what might happen if it hit us. Some of the rockets never made it to the UK, falling into the sea or coming down on Dutch territory. The V1 was followed, before long, by the V2, considered to be the forerunner of the space rocket. The V2 only needed a launching pad, such as a city square, which had an added advantage. Allied aircraft were hesitant in attacking them. Before a launch, nearby residents were ordered to vacate their homes immediately, and one city square after another would be used as a launch pad for these weapons. At takeoff, the noise was deafening, but, strangely enough, their destructive capacity was less than the Germans would have us believe in their war propaganda.

Food parcels

In March 1945, the Shell Company took steps on behalf of its employees and put together a food distribution scheme. Our house was selected as a distribution point and, twice a week, a truck delivered basic food, such as cabbages, cheese, grape sugar, and so on. The consignment had to be carefully weighed and packed for distribution. The neighbours assumed we were running a black market racket from our home. Shell was able to obtain this food from the provinces in the north, as my mother had done. Fuel for cooking was unobtainable, so people resorted to chopping up any combustible material in their homes for this purpose. Trees in streets and gardens disappeared. Tiny mini-stoves, known as 'majos', became very popular. These used a minute amount of fuel efficiently, lit using wicks floating in oil.

An amazing aspect of war is how, in times of immense crisis, people stand together and disregard individual differences. The situation, in the early months of 1945, had become desperate. There was a very real danger that epidemics might break out, especially typhus or cholera. Even the Germans knew that these diseases would spread indiscriminately. Thus, they allowed the neutral Swiss and Swedes to bring in bread for distribution to the Dutch. This, on its own, was not enough, however. Six million people were starving. Negotiations between the German and Allied commands led to the daily dropping of food parcels from the UK to the Dutch in the western regions. The small aerodrome of lepenburg, near our home, was selected to receive these airborne parcels, as were other suitable areas. I became a member of a collecting team and a system of collection evolved. This involved, firstly, a reconnaissance aircraft, flying high in the sky, setting off a flash. This was the signal to clear the field and that the dropping of food was to commence in fifteen minutes. Dozens of transport aircraft would then typically appear, flying very low and dropping army rations. After the drop, the collecting team would rush out onto the field with wheelbarrows and collect the parcels as quickly as possible. Then the next flash would go off in the sky and the exercise would be repeated, and so it went on, day after day. For some people, this rescue mission came too late. Their shrunken stomachs could not tolerate the vitamin-enriched food.

The end of the War

Radios having earlier been confiscated (some people listened clandestinely using wind-driven generators), news of the progress of the war came to us by way of newsletters, copied using a Gestettner machine and dropped into people's post boxes after the curfew. The newsletters had names like 'Het Parool' or 'Trouw ' and some, after the war, became fully-fledged newspapers in their own right. The Dutch service of the BBC, 'Radio Oranje', gave daily broadcasts and news filtered through. Early in May 1945, the Germans surrendered and Holland, above the Rhine River, became a free country once again (southern Holland had been in Allied hands since September 1944). The festive mood among the population after the German capitulation knew no bounds. In The Hague, for six months afterwards, there were street parties with dancing every night in a different part of town. We heard the sounds of American jazz bands again, after having been deprived of these sounds for five long years, American Negro rhythms having been declared strictly 'verboten'. Nazi collaborators were dealt with severely; some were put to death and others were unable to find employment for years afterwards. Young women who had befriended German soldiers were paraded around with their hair shaved off. Times were hard. Not long after 1945, Holland relinquished its colonies in the Far East and it took the Dutch economy at least twenty years to find its feet again.

Surrendered German soldiers trudge wearily through the Dutch town of Echt,

recently liberated by the Allies (Photo: SANMMH).

The following appeared in the Military History Journal Vol 14 No 1 June 2007

ERRATA

MILITARY HISTORY JOURNAL, VOL 13 NO 6, DECEMBER 2006

Please note that the following errors appeared in the article by Robert Feenstra, 'Occupation! The experiences of a Dutch youth in the Second World War, 1939 to 1945'.

p234: The first paragraph under the heading The Allies invade' should, of course, read 'In September 1944 (not 1943), the situation in Holland .. .'

p235: Under the heading, 'No food', read, 'Central kitchens were erected in the cities at strategic points, allowing a person one meal a day in exchange for a designated coupon. In January 1945, this meal deteriorated into a plate of sugarbeet soup, which tasted extremely sweet, plus the weekly supply of a small black loaf of bread .'

p237: Under the heading, 'Food parcels', read, Tiny mini-stoves, known as 'majos', became very popular. These used a minute amount of fuel efficiently. For lighting, wicks floating in bowls of oil were lit.'

The editor apologises far these regrettable errors.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org