The South African

The South African

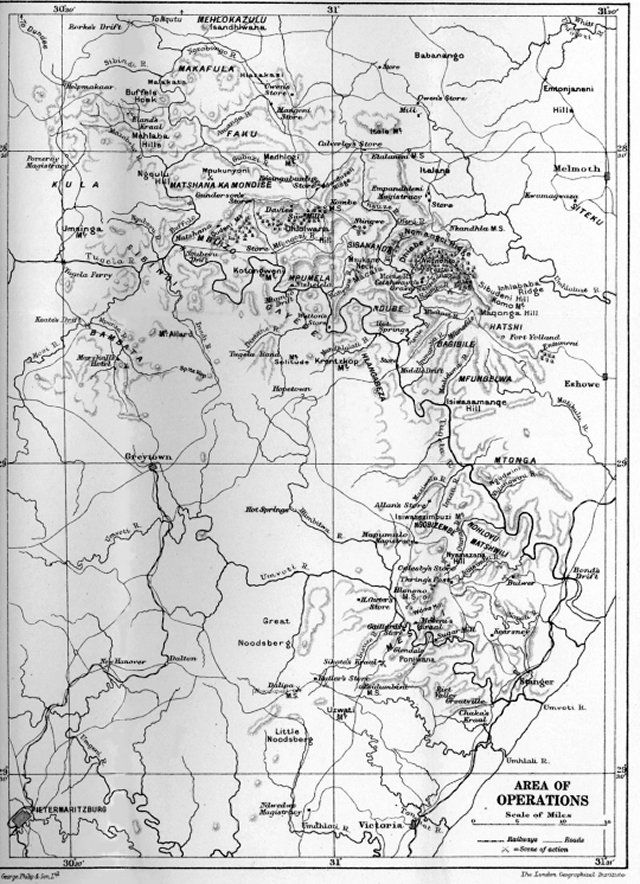

A contemporary map of the Colony of Natal and Zululand

at the time of the Natal Uprising of 1906 (drawn from

J A Stuart, The Natal Rebellion of 1906 [1913], end of index).

The gathering storm

The Umvoti Mounted Rifles (UMR) was one of several Natal colonial Militia regiments which were mobilised on various occasions in 1906 and 1907 to crush black protest against a poll tax introduced by the Natal Government in the previous year. It was the poll tax that gave rise to one of the many names given to the insurrection 'war of the heads' (iMpi yamakhanda). The longstanding grievances that facilitated a climate ripe for militant anger has been covered in detail by writers such as Shula Marks, John Lambert, Benedict Carton and Jeff Guy. Contemporary Natal settler opinion, epitomised by James Stuart and the colonial press, perceived the role of the Militia in the suppression of the protest as a commendable patriotic duty. However, as the centenary year, 2006, approached, the role of the Militia came under more critical scrutiny, perceived, for example as a tool of brutal repression.

Following the killing of two Natal Police members, Sub-Inspector Sidney Hunt and Trooper George Armstrong, in a poll tax protest related fracas at an isolated farmstead, Trewirgie, outside Richmond, on 8 February 1906, the colonial authorities reacted decisively. There were other incidents too, including one on 22 January when incensed amaNtuli chiefdom members of inKosi (Chief) Ngobizembe kaMkhonto threatened the magistrate at Maphumulo, Ernst Dunn, when he arrived to collect the new tax.

On 9 February, Martial Law was invoked. Col Duncan McKenzie, the former commanding officer of the Natal Carbineers, and arguably Natal's most renowned and ruthlessly efficient soldier, was called upon to restore order. On the following day, elements ofthe Natal Militia were mobilised and on 13 February two 'rebels' were summarily executed near Richmond and others taken into custody. A further twelve were executed on 2 April following a court martial in Richmond, held between 12 and 19 March. The white settler leadership in the Colony, including military men such as McKenzie and Lt-Col Sir George Leuchars, commanding the UMR, saw the Trewirgie incident and its fallout as an opportunity to discipline the black inhabitants and reinforce white rule.

The involvement of Natal colonial military forces in the Uprising is contentious, especially in the context of the legitimacy of white rule, and a debate has emerged among historians as to whether the settler response to black protest was exaggerated in concept and excessively ruthless in application. Militia regiments such as the UMR were inevitably infused with the convictions, mores, race attitudes, and fears of this settler ruling class. This mixture, according to Shula Marks, was one of paternalism, fear, and contempt, or in the words of Jeff Guy, 'overbearing attitudes and racist brutality'.

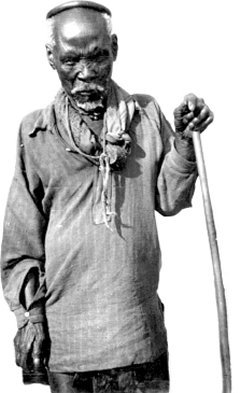

InKosi Bhambatha kaMancinza at a wedding ceremony in 1905 (KZN Museum Service).

Mounted UMR troopers on parade at the time of the Uprising (UMR Archives).

The Natal Government, in the context of the increased responsibilities for defence in terms of the Responsible Government granted it in 1893, was determined to crush this insurgency with minimal involvement from London and was sensitive to criticism of its actions towards this end. Relations between the Colonial and British governments consequently became strained when London criticised as excessively severe the settler response to the perceived threat to its hegemony. The regiments of the Colony, among them the UMR, as well as the Natal Police, and assisted by some hastily raised units from the Cape Colony and the Transvaal, as well as white levies (the Militia Reserves) and black levies, bore the brunt of military operations. The UMR, Zululand Mounted Rifles (ZMR) and Northern District Mounted Rifles (NDMR) were not included in the initial Militia mobilisation that focused on pacifying southern Natal and appeared to nip the insurgency in the bud. In April, however, protest flared up in the amaZondi chiefdom of inKosi Bhambatha kaMancinza in the Mpanza District, close to the UMR's hometown of Greytown, following an abortive effort to secure their payment of the poll tax on 22 February that had led to a panic in the town.

A UMR contingent - armed and ready (UMR Archives).

Fortified Greytown, with the barricaded Post Office, 1906

(Greytown Museum/ KZN Museum Service).

The UMR entered 1906 under the command of Col Leuchars, but when he was appointed OC Troops in Natal; command devolved on Major W J S Newmarch. During the initial phase of operations, in late February and early March, the UMR was involved mainly in the subjugation of inKosi Ngobizembe in response to the incident of defiance on 22 January and in the support of smaller operations in the vicinity of Mpanza. According to UMR Regimental Orders for January 1906, the first stirring of military activity during this eventful year was a series of parades scheduled for that month. There was no hint of the drama to come!

On 22/23 February the Natal Mounted Rifles (NMR), Durban Light Infantry (DLI) and elements of the UMR were mobilised for active service, and marched to Maphumulo, there to rendezvous with other units of the Natal Militia. This force came to be known officially as the Umvoti Field Force, and popularly as the Leuchars Field Force.

The UMR, which had been relegated to subsidiary roles in the Anglo-Zulu and the Anglo-Boer Wars, saw more extensive action in 1906, with deployment marked by the widespread 'drives' characteristic of colonial operations, as well as a roving defence of the strategic drifts over the Thukela separating Natal and Zululand. The UMR took part in 'drives' through the rugged hinterland of Zululand, at Maphumulo itself, Mpanza, Kranskop, Mpukunyoni, Mfongosi, Msimba/Msinda Valley (Thring's Post), Qudeni, and Macala Ridge. This involved deploying troops along the edge of the target area, such as a forest, and having them proceed systematically through it, driving the enemy ahead until they came up against a stop line. The problem was that numbers were often insufficient to execute these drives comprehensively, and the 'rebels' could seldom be brought to battle.

The first major task facing the Umvoti Field Force was to 'discipline' Ngobizembe. On 2 March, Col Leuchars issued an ultimatum to the chief to deliver the defiant men and when, by 4 March, the ultimatum had gone unanswered, the homestead was shelled on the following day by 'A' Battery, Natal Field Artillery, and torched. The colonial force then returned to Maphumulo to await the surrender of Ngobizembe. The UMRdoes not appear to have been heavily engaged on either 5 or 6 March, and on 10 March 1906, the Greytown Gazette, commenting on the 'Mapumulo Trouble', observed: 'On Monday the Umvoti Mounted Rifles took the field in high spirits and were disappointed because they had little fighting.' On 7 March, Leuchars and his troops paraded on a hillside near Allan's Store to receive the surrender of the 'dissident' chief. A fine of 1 200 cattle and 3 500 goats was imposed. Ngobizembe was also divested of his authority over two-thirds of his chiefdom, which was fragmented into three parts. Following the action against Ngobizembe, the UMR marched back to Greytown where it was stood down on 17 March. However, as events soon proved, there was more to come.

A UMR column departing Greytown on active service (UMR Archives).

The success of the Maphumulo operation was confirmed by an entry in Brigade Orders on 6 March:

'The OC [Leuchars] is very pleased with the behaviour of the troops during the operations of yesterday and today. He observed with pleasure the keenness and steadiness of all ranks. The disposition of the troops on both days was excellent, and all movements were executed with precision and promptitude.' Of course, the reported 'zeal and efficiency' of the troops has to be considered in the light of a total lack of opposition in what amounted, in reality, to little more than a rounding up of stock, no doubt as a deterrent. According to Jeff Guy, the 'zeal and efficiency' of the Militia throughout the Uprising included cutting a swathe of terror through the district in order to make an example of Ngobizembe and other amakhosi and their followers.

Intelligence work, normally the preserve of the magistrates and Police, became largely a military preserve during the Uprising, and it was in this context that Sergeants Elias Titlestad and William Calverley of the ZMR were to demonstrate their mettle. On 3 April the UMR was mobilised once more, in response to a further crisis, this time a stone's throw from Greytown itself. Bhambatha had returned to his Mpanza stronghold from a sojourn in Zululand, armed, he thought, with a blessing from inKosi Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo to invoke insurrection, and determined to regain the chieftainship of which the colonial authorities had stripped him. Greytown was once more prepared for defence. Men of the UMR available locally were despatched to patrol the northern approaches to the town.

Insurgency flares up On 4 April, a Natal Police contingent was ambushed at Mpanza. Four men were killed outright in the subsequent melee and this incident sent a clear message to the Natal Government that a new crisis had erupted. As far as the insurgents were concerned, the apparent victory over colonial forces gave impetus to their cause. The Colony prepared for war, and the UMR was reactivated. In the immediate wake of the skirmish, UMR patrols were pushed out to the border of the Mpanza location along the road to Keate's Drift.

Leuchars was convinced that a mere police action, irrespective of its outcome, was insufficient to quell further revolt. He gathered a force comprising elements of the UMR with two Maxim guns, four 15pounder guns of the Natal Field Artillery (NFA) for artillery support, plus a detachment of the DLI, along with transport and ambulances. The Greytown Gazette of 7 April reported on these developments: 'All available men of the Umvoti Mounted Rifles are proceeding to support the Police, and tomorrow special trains will arrive with the Natal Field Artillery, Durban Light Infantry, and some other forces of the Militia.' Leuchars also requested the mobilisation of followers of inKosi Sibindi's amaBomvu as levies. The participation of Sibindi was motivated partly out of appreciation for refuge granted in Natal from persecution in Zululand, and partly on account of rivalry with Bhambatha's people. The levies' war chant was, reputedly, 'bamba Bambata'. The position of Sibindi, as opposed to that of inKosi Sigananda kaSokufa of the amaChube, for example, illustrates the varied, localised, reasons among chiefdoms, notwithstanding the overall plight of black people, for collaboration or protest.

The UMR participated in searching Bhambatha's stronghold from 6 to 8 April. On 6 April, Bhambatha fled once again, or perhaps it was a strategic retreat, this time to Sigananda's rugged Nkandla District. Two days later, Sibindi's men joined forces with a squadron ofthe UMR for the first of several sweeps of the countryside. A correspondent for the Natal Mercury commented: 'The UMR is composed of men used to a country life, and accustomed to being in the saddle for hours daily. They were invaluable as scouts, finding their way across most difficult country, and penetrating into dense bushveld with ease.'

Bhambatha's arrival at Nkandla thrust the aged in Kosi Sigananda into the limelight as one of the major Uprising personalities. In mid-April, Sigananda became the most senior Zulu chief to throw in his lot with Bhambatha and the Uprising. Leuchars realised that more troops were required to combat the spreading insurgency. He faced a harsh geographical reality - the battleground of the Zululand frontier region, with its mountains, gorges and forests, especially the rugged Nkandla district, was ideally suited to evasion tactics and concealment of the 'rebel' impis, and posed a severe challenge to colonial horsemen and infantry.

Leuchars requested the formation of a new field force in Zululand if the insurgency was to be contained. Reinforcements were needed to secure exposed magistracies and check insurgent activity. In 1879, the Zulu maxim had been 'fight us in the open'; now it was 'fight us in the bush'. As events were to prove, the results were disastrous for the insurgents when they abandoned this tactic of evasion in favour of frontal attack, such as at Bobe Ridge (5 May) and at Mpukunyoni on 28 May.

The colonial campaign was ground-breaking. It was the first major military campaign conducted by a British colony without direct assistance from the Mother Country. The main strategy used was to converge on Nkandla Forest, the major 'rebel' stronghold, while the UMR also patrolled the Thukela River frontier zone. There existed an underlying tension based on the premise that those passively sympathetic to the rebel cause might join the rebellion if the colonial forces suffered a reverse. Consequently, considerable caution had to be exercised to avoid providing a spark.

Between 4 and 21 May, the Umvoti Field Force patrolled in the vicinity of Hot Springs in the Thukela River border area of Zululand and the UMR was scattered over several locations. During May Government forces appeared to have stabilised the military situation, and little firm contact was made with 'rebel' forces, but there was plenty of activity nonetheless. Colonial troops set fire to homesteads and confiscated livestock in an attempt to force the rebels into submission. Major drives on 15 May and from 17 to 20 May were exceptions to the generally modest level of operations.

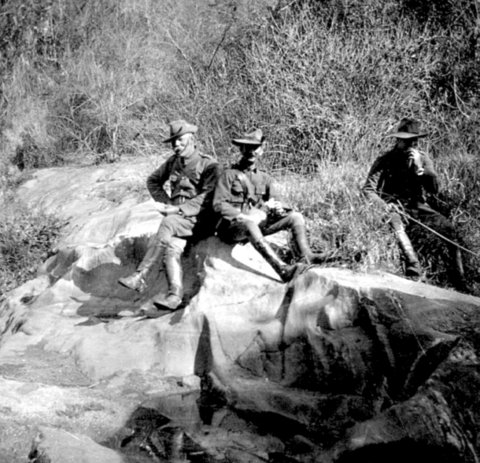

An informal group photograph showing Lt-Col George Leuchars (left),

Major Samuel Carter (centre) and Lt M Norton (UMR Archives).

InKosi Sigananda kaSokufa (UMR Archives).

At this point it became apparent that the Nkombo Bush and Qudeni Mountain had also emerged as 'principal lairs of the enemy', and that this situation called for cooperation between the several columns operating against the 'rebels'. The Umvoti Field Force, together with Sibindi's men, moved on 27 May to join Mackay's troops to operate along the Mzinyathi (Buffalo) River downstream from Rorke's Drift. Considerable destruction was visited upon communities suspected of disloyalty in the region of Qudeni. They then pressed on to Mpukunyoni.

The ZMR first arrived at Nkandla on 9 April. Two troops joined the Natal Police in operations in the vicinity of the Nkandla Forest. On 30 April, the NDMR arrived from Babanango and joined the ZMR in operations in the vicinity of Ntingwe; the two Zululand regiments remaining in the Nkandla region during May and into June. On 5 May, a column, under the command of Lt-Col Mansel of the Natal Police, engaged in an action at Nkomo Hill, in the vicinity of the Nkandla Forest, was attacked by a rebel force, thought to have been commanded by Bhambatha himself. Mansel estimated approximately 60 fatalities, plus numerous wounded, amongst the rebels, while colonial casualties, amounting to a few wounded, were negligible. The heavy rebel losses were a setback for Bhambatha, disspelling his assertion of immunity against colonial guns, and many of his followers deserted.

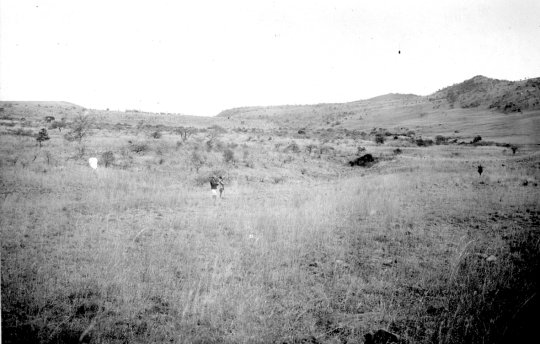

The battlefield of Mpukunyoni (UMR Archives).

On 9 May, Col McKenzie further beefed up the cordon of troops at Nkandla in preparation for a major move on the rebel forces. Several reconnaissance expeditions were mounted. The Zululand Field Force conducted determined sweeps through the Nkandla Forest region from the middle of May to early June. The ZMR and the NDMR joined a column that marched on the Insuzi Valley and Cetshwayo's Grave on 16 and 17 May, leading to a skirmish, followed by the customary confiscation of stock plus the torching of suspected homesteads.

On 19 May emissaries from Sigananda approached Col McKenzie at Nkandla with the purported intention of facilitating his surrender. The ZMR formed part of the military muscle deployed by McKenzie over the next few days to secure this' important surrender. However, the military presence, together with convoluted negotiations with emissaries of the chief, failed to yield the desired result.

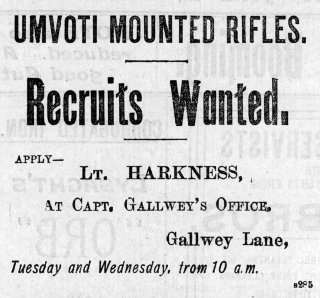

A UMR recruiting notice which appeared in the Natal Witness,

12 June 1906 (KZN Museum Service).

On 28 May, at Mpukunyoni, the Umvoti Field Force encountered 'rebels' in a major clash. The UMR, the Umvoti District Reserves (largely of Afrikaner stock) and Sibindi's levies formed a square to repulse an attack. The rebels sought to envelope the camp in the typical Zulu manner, but ended up making a frontal attack, under the cover of thick bush, on the eastern face held by the UMR. Cattle driven by the attackers across the face of the square held by the Headquarters and City (Pietermaritzburg) squadrons of the UMR to create a diversion, were quickly shot down. Repeated rebel rushes were repulsed on all sides by intense rifle fire, but it was snipers, firing from a ridge about 800m away, using Mausers (and therefore smokeless powder) and concealed in excellent cover, who caused the most damage to the colonial troops.

During the engagement, the UMR men off-saddled and took shelter behind their saddles to do battle. This clever precaution contributed to their minimal casualties. The black levies remained largely inactive within the square, only emerging when the attacks had subsided to pursue and assegai the retreating rebels. Trooper H Scott Steele from the Umvoti Division Reserves was killed by snipers, several levies also lost their lives and a handful of UMR troopers were wounded. The rebels lost heavily, with 80 to 100 killed. On 30 May Col Leuchars departed for Helpmekaar to assume duty as OC Troops in Natal and the Nqutu District of Zululand. Col McKenzie was by then in overall command of the Colonial Troops in the field. Command of the UMR and the Umvoti Field Force devolved to Major Newmarch.

During June and into July the UMR returned to its core function of scouting and reconnaissance, far from the heart of military operations at Nkandla that were to culminate in the decisive events at Mome Gorge on 10 June, although its compatriots in the ZMR and NDMR were closely involved in that crucial action. The NDMR narrowly avoided disaster on 3 June, when, along with Royston's Horse and the DLI, it was ambushed by rebels along the Nkunzana Stream in the vicinity of Mome Gorge. Five men died, heavy casualties for the colonial forces, while the insurgent fatalities were typically heavy, an estimated 140. The ZMR and NDMR were involved in further drives over the next few days. Then, on 9 June, came the electrifying intelligence from the ZMR's Lieutenant J S Hedges and Sgts Calverley and Titlestad, local residents who had formed an intelligence and scouting component within the Zulu/and Field Force, that led to the clash at Mome Gorge. In their efforts to track down the aged but elusive Sigananda, this trio learned that a large 'rebel' force was to congregate at the confluence of the Mome and Nsuze rivers, thus precipitating the decisive engagement at Mome Gorge on the following day.

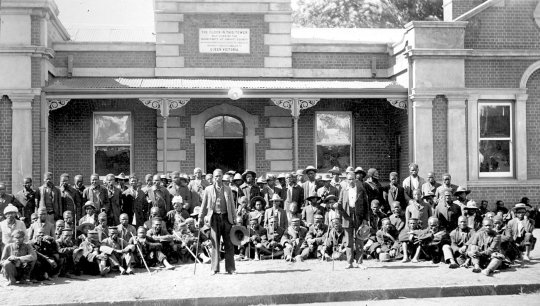

'Sibindi's Levies' outside the Greytown Town Hall

towards the end of the Uprising (UMR Archives).

McKenzie's intention was to surround the rebel force before it entered the Nkandla Forest. To this end, a force under Lt-Col W F Barker was despatched during the night to the mouth of the Mome Valley to intercept. During the night of 9/10 June, ZMR Troopers C W Johnson, W Dealley and G O Oliver carried this crucial order through rebel concentrations in the Nkandla Forest to Barker's Headquarters, arriving at a 1.15. The subsequent battle, a furious though brief one, lasted from 06.45 to approximately 07.50.

The bulk of the ZMR, along with their compatriots from the NDMR, played a significant part in the vicinity of Dobo Forest on the afternoon of 10 June, acting as a blocking force during the pursuit of the rebel warriors scattered in the dawn attack at Mome Gorge. Captain O J C Hulley, adjutant of the ZMR, reportedly urged his men on with the exhortation, 'Buck up ZMR! This is a chance in a lifetime.'

Lt F S Rundle of the NDMR was personally credited with shooting inKosi Mehlokazulu kaSihayo, one of the leading insurgent commanders. The Government forces killed up to 500 insurgents, and almost certainly Bhambatha himself, at the cost of one of their own killed and a dozen wounded. The colonial commanders, Government, and press were all convinced that the Uprising had at last been crushed. On 11 June, the Natal Witness confidently carried headlines such as 'Splendid victory' and 'Rebel power broken'. Subsequently, at Nomanci, Hedges and Calverley were detached to effect the longawaited capture of Sigananda. The elusive chief duly surrendered on 13 June, was courtmartialled at Nkandla from 25 to 28 June, and died soon thereafter.

During the Course of June, nearly 1 000 rebels in the Nkandla District surrendered to the colonial forces. However, despite the colonial success at Mome, talk of the complete Suppression of the Uprising was premature. In mid June, the conflict flared up once again in the Maphumulo region, where followers of Ndlovu kaThimuni, Ngobizembe (the UMR's old nemesis from earlier on in the Uprising, but now himself imprisoned), Mbombo kaSibindi Nxumalo, and Meseni kaMusi of the Qwabe rose in open rebellion. This episode of unrest was motivated in part by the severity of the Militia response to several attacks on white civilians. The Umvoti Field Force was again called into action. Columns comprising the UMR, ZMR and NDMR concentrated at Maphumulo and embarked again on drives to flush out the insurgents. Unrest also threatened the Noodsberg region, in UMR territory, and on 26 June it was proposed to despatch the UMR to stand sentinel there. Operations nevertheless remained focused on Maphumulo and the colonial forces descended on the district with a vengeance.

On the evening of 2 July a wagon convoy escorted by 50 men of the ZMR, 17 from the NDMR, and 72 from the DLI, was attacked by an estimated 500-strong impi at Macrae's Store, some 20km from Bond's Drift. Captain Hulley, with four mounted men of the ZMR, constituted an advance guard, and flanking troops were also in place. Despite these precautions, however, three attacks followed, repulsed by rifle fire and case shot from field guns. Recently introduced Rexer machine-guns also saw service for the first time on this occasion. One man was lost, Trooper Gudmund Coli of the ZMR, as well as the ZMR's dog-mascot, which, running ahead of the wagons, had raised the alarm.

Colonial troops saw further action in early July in the vicinity of Maphumulo and adjacent districts as McKenzie sought to eradicate this final blaze of insurgency, causing heavy casualties amongst the rebels at the Newspaper Mission Station and at the Insuzi River on 2 July. McKenzie then deployed his columns against rebel concentrations in the vicinity of inKosi Meseni's homestead at eMthandeni. On the next day, at Mpumulwana, Wools-Sampson's column inflicted another costly defeat on the insurgents in two separate engagements. In the first of these clashes, NDMR and ZMR contingents, along with a detachment of Royston's Horse, took part in a flank attack on the impi. During a drive that followed, the NDMR beat off a resolute attack. It is this late phase of the Uprising in particular that has aroused the ire of several historians regarding the apparently extreme scorched-earth nature of the sweeps and 'mopping-up' operations, which caused heavy casualties among the insurgents. Col Leuchars was singled out for special criticism. McKenzie, however, probably reflecting the dominant Natal Government and settler opinion at the time, felt that the action taken was necessary and justified.

On 8 July a final, major battle took place in the Izinsimba Valley, when columns under Leuchars, MacKay and Wools-Sampson, including elements of the UMR, ZMR and NDMR, converged on the homestead of inKosi Mashwili kaMngoye of the Mthethwa. An estimated 547 of Mashwili's men were killed in what proved to be the end of the military campaign. On 10 July, the UMR returned to Maphumulo to prepare for disbandment. Four days later, McKenzie suspended offensive operations to allow the remaining insurgents to surrender. The ZMR and NDMR saw out the final days of the Uprising at Kranskop.

Aftermath Demobilisation followed on 30 July. The UMR troops entrained at Tongaat for home on 1 August, and arrived in Greytown early the next morning. An official welcome was extended at the Town Hall.

'Every man, woman and child of Grey town,' extolled the Greytown Gazette, 'appeared to be present, and the heartiest of welcomes was given to [the] returned troops.' Mr W K Ente, chairman of the Greytown Local Board and father of Jacob Ente, NDMR, delivered the sort of grandiloquent address typical of such formal civic occasions: 'The fame of the UMR would live in history and they would stand out in bold relief as the saviours of the country in time of extreme peril.' The considerable exaggeration of the UMR's modest role is apparent.

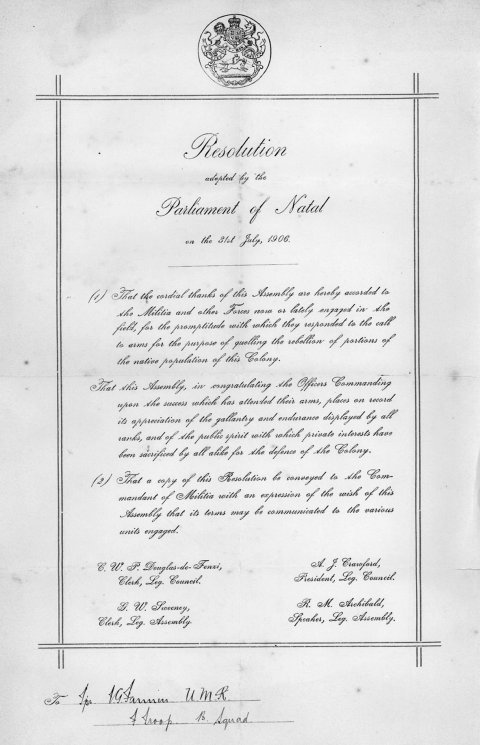

The resolution passed by the Parliament of Natal on 31 July 1906,

praising the colony's military forces for a job well done. This particular

document was issued to Trooper V G Fannin of "B" Squadron, UMR.

(UMR Archives)

The ZMR were also given a warm welcome when they passed through Greytown en route home to Eshowe. The City Squadron of the UMR participated in the general parade on the Market Square, Pietermaritzburg, on 2 August, where the Governor addressed the returning troops with further effusive praise. The residents of Vryheid welcomed the NDMR home on 4 August with more modest fanfare and, in Eshowe, the ZMR were welcomed home with a parade on 7 August. On Saturday, 25 August, a special 'welcome home' gymkhana was held in Grey town for the UMR, preceded by the obligatory Friday Evening Ball. The programme of routine gymkhana events was spiced up with the addition of one event with a special Uprising twist - Event No 8, 'Spearing Bambata', required competitors to negotiate a hurdle while at the same time spearing a stuffed dummy!

Casualties among the Natal Volunteer forces had been negligible. The ZMR had lost Trooper Coli in the convoy ambush at Macrae's Store on 2 July, and Sgt H A James, of the City (Pietermaritzburg) Squadron, who died in Grey's Hospital on 20 October 1906 from dysentery contracted while on active service in the Uprising.

Lt-Col Leuchars made a show of publicly acknowledging and thanking the levies that Chief Sibindi had put into the field in support of the colonial forces. At a ceremony held a few days later at the Courthouse in Grey town, Leuchars acknowledged the risk taken by Sibindi and his followers in respect of the potential resentment of black supporters of the rebels. Sibindi was concerned that the Government might forget the sacrifice of his people and expose them to retribution. In contrast, Col McKenzie, the commander of the Natal troops, held a distinctly jaundiced opinion of their loyalty and efficiency. In his view, the levies only really became useful in clearing up after an engagement, as well as in collecting and driving cattle.

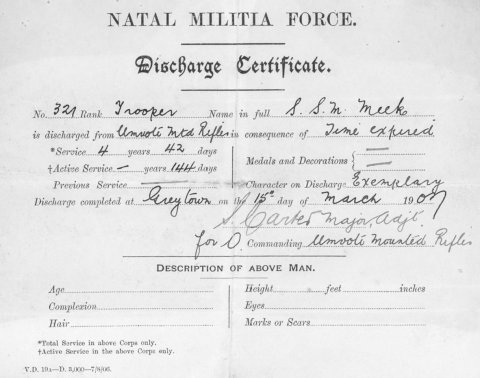

Departure from the military in the wake of the Uprising:

Trooper SSM Meek's discharge certificate from

the Natal Militia Force, 15 March 1907 (UMR Archives).

The political and legal fallout of the Uprising had yet to be resolved. The region remained tense and the Natal Government was determined to use legal action to reinforce the military success it had achieved over the insurgents. Trials took place under Martial Law and against a background of continuing punitive action. The settler population remained edgy and vindictive for the balance of 1906 and into 1907. On top of the agenda for the Natal Government was the arrest of Dinuzulu, who, despite not having taken an active part in the insurrection, stood accused of complicity and high treason, mainly because of his association with Bhambatha and a tangled web of rumour and conjecture surrounding him. Evidence suggests that, regardless of his sympathy with the cause of liberation underpinning the insurgency, it is unlikely that he would again have risked confrontation with the might of white rule after a previous abortive military protest in the 1880s.

On 7 December 1907, Martial Law was re-imposed and the Militia, including the UMR, ZMR and NDMR, assembled once more, this time to apprehend Dinuzulu and to quell the campaign of assassination directed at Government loyalists. It was Major Newmarch who led the UMR when the Natal Militia and Natal Police Field Force assembled at Gingindlovu and proceeded to Somkele and thence to Nongoma and the uSuthu homestead to arrest Dinuzulu without incident on 9 December. It was during this period of mobilisation that the UMR suffered another fatality, and a bizarre one at that. Corporal J J Tissiman was doing his rounds of sentry posts at a camp at Somkele in Zululand when he inexplicably failed to answer the challenge of a sentry and was shot dead using the controversial expanding or 'dum-dum' Mark V variety of ammunition used by colonial forces in the Uprising.

Dinuzulu faced 23 charges, including high treason, public violence, sedition and rebellion during his famous trial, held in the Greytown Town Hall from 10 November 1908, the cornerstone of the Government's argument being Bhambatha's sojourn at the Royal homestead in March 1906 and the support for rebellion that supposedly emanated from it. Judgement was delivered on 3 March 1909. To the embarrassment of the Natal Government, Dinuzulu was only found guilty on a handful of the charges. He was sentenced to four years' imprisonment and a fine of £ 100.

Campaign medals for the recent Natal Uprising, officially called the 'Natal Native Rebellion 1906 War Medals', were issued in terms of Militia Order No 128, dated 9 May 1907, and published in the Natal Government Gazette on 14 May. The Governor of Natal, then Sir Matthew Nathan, presented 422 medals to the UMR at a parade on Wednesday, 12 August 1908. The minimum period of qualifying service was twenty days in Natal and/or Zululand between 11 February and 3 August 1906.

Apart from the campaign medal, Col Leuchars was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), and Major Samuel Carter was awarded the Medal for Meritorious Service, along with Major W A Vanderplank and Lt J S Hedges of the ZMR. The ZMR also garnered no fewer than five Distinguished Conduct Medals, the recipients being Squadron Sgt-Maj William Calverley, Sgt Elias Titlestad, and Troopers W Deeley, W Johnson and G W Oliver. Good Service decorations were awarded to Troopers T J Bentley and R W Sharpe of the NDMR.

Some concluding comments In this Centenary year of the Natal (or Bhambatha) Uprising, historians and other interested parties are dissecting its causes, conduct and significance. At face value, the disjointed Uprising had been crushed, and the colonial forces, with the assistance of black levies, had inflicted heavy losses (an estimated 1 500 killed) at negligible loss to themselves. Modern weapons and military efficiency had seen to this, and it was primarily the irregular nature of the fighting in the remote and rugged interior of Zululand that drew the campaign out over several months.

Historians will generally agree that the Natal Uprising was a tragic episode. It cost many lives, the vast majority of them black inhabitants of the regions scoured by colonial troops. It traumatised thousands more, as an anxious Natal settler government, fearful of surrendering its authority, sought to crush the insurrection with all the resources at its disposal. For many years, the Uprising was considered to be the 'last of the Native wars in South Africa', and it has since acquired status as the foundation phase of concerted resistance to white rule. The Centenary provided Reserve Force regiments of the post-1994 democratic dispensation, such as the UMR, with an opportunity for reconciliation with former foes.

The role of the Militia regiments, foot soldiers of the settler colony, has so far received cursory treatment. Regimental histories have traditionally been blandly neutral on the topic of the Uprising. Academic history has been more critical. Jeff Guy, in his book, The Maphumulo Uprising - War, Law and Ritual in the Zulu Rebellion (2005), has, however, controversially asserted that the troops of the Militia regiments, such as the UMR, who participated in military operations to suppress the Uprising, were little more than 'armed racists' and terrorists. Regiments such as the UMR, the ZMR and the NDMR were inevitably spawned by the paradigm of white hegemony, Empire, masculinity and colonialism. Did their involvement in this campaign make them gratuitous killers? The reader is asked to consider this question and judge these men in the context of their time and place. On the question of alleged atrocities, there are several claims to be considered, including the assertion that, at Mome Gorge, colonial forces offered amnesty to wounded warriors and others if they emerged from hiding, only to kill them in cold blood when they complied. Oswald Smythe, son of the Natal prime minister, Charles Smythe, was reportedly sickened by events at Mome. What also, as a concluding thought, is to be made of the use of expanding or 'dum-dum' bullets, designated Mark V and VI ammunition?

SOURCES

The following archival resources were consulted in the compilation of this article:

Greytown Museum

Umvoti Mounted Rifles, Diary of Operations, 1906 (Original, UMR).

Umvoti Field Force and Umvoti Mounted Rifles, Regimental Orders, January-June 1906, 9 June to 29 July 1906.

The Natal Native Rebellion as told in Official Despatches, from January 1 st to June 23rd, 1906, With Introduction and Diary of the Day-to-Day Operations in the Field (Pietermaritzburg, P Davis and Sons, 1906).

Natal Carbineers History Centre

'Northern Districts Mounted Rifles, Natal, 1902-1913'.

'Natal (Bambatha) Rebellion 1906', Report by Colonel Duncan McKenzie to commandant of Militia, September 1906.

UMR Archives, Red Hill, Durban

UMR Minute Paper, 'Visit of Troops to the "Usuthu" Kraal, December 1907'.

Photograph Album (brown, black, gold-Ieafj, 'UMR and General, Anglo-Boer War and Natal Uprising'.

Zululand Historical Museum, Fort Nongqai, Eshowe

'Zululand Mounted Rifles', file including ZMR history transcribed from the Zululand Times Annual, 25 December 1924.

'Titlestad family', file.

'Umvoti Mounted Rifles', file.

'An Account of the Bambata Rebellion Written by Mr Benjamin Colenbrander who in 1906 was Magistrate of the Magisterial District of Nkandhla.', typescript.

Articles and publications

Ferguson, R, 'The Umvoti Mounted Rifles, 1865 to 1906', in The Christmas Nongqai: The Natal Police Magazine, Pietermaritzburg, 1907.

Gillings, K G, 'The Bambata Rebellion of 1906: Nkandla Operations and the Battle of Mome Gorge, 10 June 1906', in Military History Journal, Vol 8 No 1, June 1989.

Greytown Gazette and Lion's River County Herald.

Mitchell, F K, 'The Natal Native Rebellion 1906 War Medal', in South African Numismatic Journal (Journal of the South African Numismatic Society, nd).

Redding, S, 'A Blood-stained Tax: Poll Tax and the Bambatha Rebellion in South Africa', in African Studies Review, 43/2, September 2000.

Thompson, P S, 'Isandlwana to Mome: Zulu Experience in Overt Resistance to Colonial Rule', in Soldiers of the Queen, 77, June 1994.

Thompson, P S, 'Bambatha's Personal Rebellion', in Natalia, 33, December 2003.

Books

Bosman, Walter, The Natal Rebellion of 1906, (London, Longmans, Green and Co, 1907).

Du Plessis, A J, The Umvoti Mounted Rifles, 1864-1975 (Greytown, 1975).

Forsyth, D R (compiler), The Natal Zulu Rebellion 1906 (medal roll), (Roberts Medals Publications, 1990).

Guy, Jeff, The Maphumulo Uprising: War, Law and Ritual in the Zulu Rebellion, (Pietermaritzburg, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2005).

Lambert, John, Betrayed Trust: Africans and the State in Colonial Natal, (Pietermaritzburg, University of Natal Press, 1995).

Marks, Shula, Reluctant Rebellion: The 1906-1908 Disturbances in Natal, (Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1970).

Stuart, J, A History of the Zulu Rebellion 1906, (London, Macmillan and Co, 1913).

Thompson, P S, An Historical Atlas of the Zulu Rebellion of 1906, (Pietermaritzburg, 2001).

Thompson, P S, Bambatha at Mpanza: The Making of a Rebel, (Pietermaritzburg, 2004).

Thompson, P S, Incident at Trewirgie: First Shots of the Zulu Rebellion 1906, (Pietermaritzburg, 2005).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org