The South African

The South African

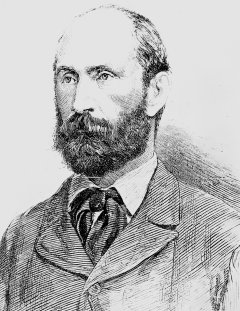

Maj Gen Sir G P Colley, KCSI, CB, CMG,

killed at Majuba, 27 February 1881.

Rather than narrate the well-known events of the 1880-1 War, this article will serve to examine the psychological state of Maj-Gen G P Colley in the last six weeks of his life. It will show how, as reflected in his own increasingly distrait writings and in the privately expressed views of the men he commanded, Colley progressively degenerated into a haunted, withdrawn shadow of the confident, efficient commander he had been at the outset of the campaign, to the extent that he proved incapable of responding appropriately to the final catastrophe that would engulf him. The article will also explore why Colley failed so badly in his three engagements with the Boers, and pose the question whether this was due to the task he had been given being beyond the resources available to him or to his own deficiencies.

History is not always fair. In retrospect, Colley and the men serving under him were probably on a doomed expedition when they set out in early January 1881 to relieve the various besieged garrisons in the Transvaal and to quell the rebellion there. Numbering well under 2 000 men of all ranks, the force was hopelessly inadequate for the task and, in the end, failed to even enter the rebellious colony. Eventually, reinforcements did arrive, but these only served to replace the heavy losses already incurred. What would emerge in the course of the 1880-1 War, difficult though it was to believe at the time, was the realisation that, man for man, the British regular troops - despite all their training, physical toughness and undoubted courage - were no match for the Boers, and that only a significant advantage in numbers would enable them to prevail.

All this may be true. Certainly, during the Second AngloBoer War, 1899-1902, the Boers were able to demonstrate that

their triumphs two decades earlier had been no mere fluke. But, at the time, Colley's contemporaries expected him to succeed and were less willing to make excuses for him. Even before Majuba, his own officers had been privately questioning his abilities as a field commander. This doubt began to surface openly after he had suffered another severe mauling, at the battle of Schuinshoogte (also called Ingogo) on 8 February 1881, as recalled by Sir Philip Marling of the 3/60th Rifles (1931, P 41):

'He was a great hand at making speeches and writing dispatches, and a more charming and courteous man you could not meet. I heard one old officer who had seen considerable service say after the Battle of Ingogo that he [Colley] ought not to be trusted with a corporal's guard on active service. It is an extraordinary thing that he made such a mess of it, as he was absolutely the star turn in what was known as the "[General, later Field Marshal Lord Garnet] Wolseley gang" in those days. He had seen active service in Ashanti, China and India and was thought so highly of that he had been offered the command of the Staff College, but he was certainly not a success in the field.'

How fair, and indeed accurate, is this rather damning assessment of the luckless Colley? Would another, more able, commander - Sir Harry Smith, for example, or even Wolseley himself - have fared any better? The answer to this question may well be 'no'.

Underestimation

Boer proficiency came as an unpleasant surprise, not only to Maj-Gen Colley, but also to Colonel Philip Anstruther. The latter was mortally wounded and his column cut to pieces in the opening engagement of the 1880-1881 War, at Bronkhorstspruit on 24 December 1880. In this, a straight firefight lasting less than half an hour, 77 British officers and men were killed or mortally wounded. In the same action, there were only two Boer fatalities.

Even before the Bronkhorstspruit disaster, the British should have known better than to under-estimate their Boer opponents. Even as far back in history as the battles of Muizenberg (1795) and Blaauwberg (1806), burgher irregulars in the Dutch ranks proved themselves to be formidable opponents against British regular troops. In the Natalia War of Independence (which is as good a name as any for the clashes that took place between the Voortrekkers and the British invading column around Port Natal in 1842), the British were soundly repulsed at Congella and subjected to a prolonged siege that only the arrival of substantial numbers of reinforcements was able to lift. At the 1848 Battle of Boomplaats, the Trekkers (they had yet to be referred to as 'Boers') were soundly defeated in the end by Sir Harry Smith. However, a closer look at even this engagement shows that Smith was given a tough fight and succeeded only because of the substantial advantage he enjoyed in terms of superiority in numbers and in artillery.

Yet, at the commencement of the First Anglo-Boer War, the British appear to have been unaware that the task facing them was not going to be an easy one. Instead, the record of previous encounters with the Boers was overlooked and the Boers' failure to prevail against the Pedi chief, Sekhukhune, just prior to the British annexation of the Transvaal in 1877, was overemphasised.

The repulse of the British at Laing's Nek on 28 January 1881 underlined the inadequacies of the forces entrusted with carrying a strong defensive position occupied by well-armed Boer marksmen. There had been nothing wrong in particular with Colley's plan of attack. In summary, this had involved the launch of an infantry assault by several companies of the 58th Regiment up a spur leading to the plateau, with a small mounted squadron sallying out in support to the right and the 3/60th Rifles and Naval Brigade deployed in reserve in the centre and left rear. This assault was preceded by a short artillery bombardment (which was undoubtedly called off too soon on the mistaken assumption that it was having no effect on the Boers). The attack quickly went awry, the mounted men deploying too far to the right to attack a hill, being ignominiously repulsed and playing no further part in the battle. The 58th, by then enfiladed on both flanks, were forced by their over-eager, mounted officers to ascend the steep slopes at an exhausting pace in the morning heat. On finally ascending the crest, they attempted a charge but were quickly mowed down by a withering fire from the Boer riflemen safely positioned behind stone sangars. British casualties were 83 killed (including seven officers) and over a hundred wounded, a number of these subsequently succumbing to their wounds. Only fourteen Boers lost their lives.

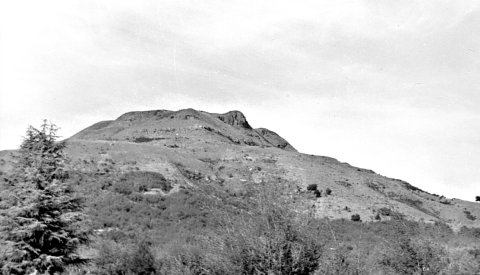

The site of Colley's last stand, as it appeared ten years ago

[i.e. in 1996 - Photo D Saks]

What shook Maj-Gen Colley at Laing's Nek was not only the relative ease with which the Boers repulsed his forces, but the high death toll as a result of it. Apart from Isandlwana, this was the highest casualty toll for British regular troops in any earlier engagement in South Africa (slightly more had been killed at Hlobane during the Anglo-Zulu War, 1879, but most of these had been colonial irregulars). For Colley, whose previous military experience had been confined to the comparatively bloodless from a British point of view Ashanti Campaign of 1873-4 and the Anglo-French Expedition to China in 1860, this was something new. Having to preside over the burial of many of his fellow officers, who only a few hours before had been his friends and confidants, was a deeply traumatic experience. It would be the fatal wounding of yet another colleague, Commander Francis Romilly of the Naval Brigade, early in the Battle of Majuba that would seem to demoralise him utterly and contribute to the ensuing chaos in the British ranks when the Boers began pressing home their advantage.

The one-on-one superiority that the Boers enjoyed over their opponents, already proven at Bronkhorstspruit and Laing's Nek, came to the fore again at Schuinshoogte. Here, the British were unexpectedly attacked in the course of what had been intended as a demonstration of strength to discourage Boer interference with Colley's lines of communication. Colley's force was severely mauled and only extricated from its precarious position under the cover of night. More than seventy of Colley's men, mainly from the 3/60th Rifles, were killed or died of wounds, including a number who drowned in the Ingogo during the retreat. Despite their having gone onto the offensive during this action, there were only ten Boer fatalities. The British disasters at Laing's Nek and Schuinshoogte, apart from their obviously demoralising effect, resulted in a combined total of nearly 500 casualties out of a total force of no more than about 1 800. Almost as many were killed or died of wounds as were wounded, a distinctly high fatality ratio.

A view of Majuba, scene of Colley's last fight (Photo: SANMMH).

A crucial battle The action at Laing's Nek effectively halted Colley's advance in its tracks and left him in no position to renew the attack for a full month, during which intensive negotiations took place between the British and Boer governments, President Brand of the Orange Free State playing an important mediator role. What helped the cause of peace was that, even in Britain, the 1877 annexation of the Transvaal had not been universally welcomed. For the British public, the annexation had caused yet another costly colonial war and this gave credence to the voices of its dissenters. Had Colley succeeded in forcing the Laing's Nek passage, which would have enabled him to relieve the besieged British garrison at Standerton, Boer leverage at the negotiating table would have been greatly weakened and their military resistance may have collapsed altogether. It could be argued reasonably, therefore, that Laing's Nek, and not Majuba, was the crucial battle of the First Anglo-Boer War.

It is nevertheless understandable that Majuba, fought on 27 February 1881, is generally viewed as the decisive battle of the 1880-1 War. The magnitude of the British defeat on that fateful hill clearly demonstrated to the British Parliament that to re-win the Transvaal, a significantly greater commitment in men and expenditure would be necessary. Following two expensive ventures against the Zulu and the Pedi in 1879, not to mention the 9th Frontier War (1878) and the campaigns in Griqualand and Basutholand, this was seen as one colonial adventure too many. While undoubtedly sealing the Boer victory in the War of 1880-1, Majuba may have been superfluous. A peace agreement had almost been reached and thus the military engagement which can really be said to have decided the outcome of the war was Colley's failure at Laing's Nek. Without the Boer success at Majuba, would the negotiations have been concluded in favour of the Transvalers regaining their independence? This is an open question and no doubt influenced Colley's final, increasingly agitated, dispatches, showing his growing obsession with the likelihood that politicians would try to deprive him of an opportunity to make amends for his previous military failures.

While appearing outwardly as cool and collected as always, it is all too evident that, towards the end, Colley was undergoing a progressive emotional breakdown. Tormented by the perceived 'disgrace' of Laing's Nek and aware that the Schuinshoogte fight was being widely interpreted as a British defeat despite his best efforts to represent it as a success, Colley was desperate for a redeeming victory before it was too late. Philip Marling (1931, p55) later wrote of Colley that 'after Ingogo, he hardly slept at all, and used to be writing, always writing, in his tent half the night' . An unidentified officer told the correspondent for the Natal Mercury that 'another defeat will kill Colley'. It was later suggested that Colley's ambitious wife, in Pietermaritzburg, to whom he wrote incessantly, pouring out his hopes, ambitions and fears, had been pressing him into doing something to salvage his disintegrating reputation. According to rumour, in one particular letter, which mysteriously disappeared, she is said to have sharply criticised her husband for not acting decisively before matters were taken out of his hands. This is a theory which, though plausible, is unlikely ever to be proven either way.

Following the Schuinshoogte engagement and with a peace deal beckoning, Colley turned his eyes obsessively onto Majuba, the imposing bastion on the far right of the Boer position. It was Majuba that he eventually chose as his vehicle to redemption, not only for himself, but for his men too. It was apparently for the sake of his men that he decided to include contingents from all the regiments under his command when he set out for Majuba. A London war correspondent for the Standard, John Cameron, believed this to be the case, when he wrote in his report on the battle: 'I learn that General Colley, feeling himself assured of success, wished that every regiment in his camp might have a share in the victory he expected to win. He hoped that the 58th would wipe out Laing's Nek, and the Rifles the Ingogo' .

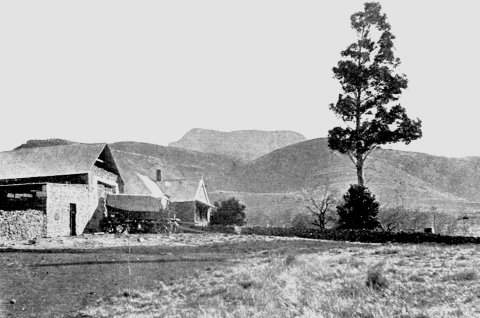

O'Neill's Cottage (below Majuba), where the 1881 peace treaty was signed

(Photo: SANMMH).

However worthy the sentiment behind Colley's thinking may have been, this decision turned out to be a serious error. As the battle progressed, the various detachments became hopelessly intermingled. In the confusion that followed, regimental cohesion, esprit de corps and troop morale began to disintegrate rapidly. This helps to explain why the British fought so very badly at Majuba in comparison with the two previous engagements where, despite their losing cause, they had shown great courage and discipline.

One could argue that Colley's obsession with keeping up appearances and being seen to be doing the honourable thing at all costs was at the heart of his error of judgment. This obsession may also have been a factor in his decision to attack Laing's Nek with an obviously inadequate force rather than await reinforcements and risk being accused of timidity in the face of the enemy. The crowning disaster of Majuba could have been avoided in its entirety had Colley not been so desperate to make one last attempt to redeem himself as a military leader.

Colley's handling of the Laing's Nek affair had not been demonstratively inefficient and the coolness and personal courage he displayed at Schuinshoogte could not be called into question. The assessment of his performance at Majuba must, however, be criticised more harshly. From the firing of the first shot, Colley failed to take control of affairs and allowed the increasingly confident Boers to dictate the course of events. At this moment of crisis, both he and the demoralised men serving under his command were found to be sadly wanting.

Survivors of Majuba later commented on the surprising passivity shown by Colley once the summit of Majuba had been occupied. He showed no intention to do more than hold the position and await the next move by the Boers, possibly hoping that the Boers, finding that they had been outflanked, would simply abandon their positions. Perhaps he anticipated, as he had commented to Sir Garnet Wolseley, at last having his 'Kambula after his Hlobane' - a wistful reference to how, during the Anglo-Zulu War, his colleague, Sir Evelyn Wood, had been able to nullify the impact of the Hlobane disaster by bloodily repulsing a Zulu attack on his Kambula camp the following day. Colley had long hoped that the Boers would try to assault his Mount Prospect camp and be soundly beaten. Evidently, he was confident that his men would be able to hold so naturally strong a position. One can only speculate as to what went through his mind as the Boers, instead of retiring, set about attacking in force.

Lieutenant (later the renowned General Sir) Ian Hamilton was one of the few on the British side to emerge with credit from the disaster of Majuba. In his own account of the fight, 'A Subaltern at Majuba' in the Tiger and Sphynx, Vol 3, No 16, 20 March 1927, pp151-4, Hamilton describes how Colley dismissed his repeated warnings that the Boers were preparing to storm the summit, as well as his plea for a bayonet charge to be launched after the loss of the crest. The last straw for Colley appears to have been the fall of yet another fellow officer and close friend, Commander Francis Romilly of the Naval Brigade, mortally wounded in the abdomen by a long-range shot from below. Survivors later commented on how silent Colley became after this event. 'It is said that when the wounded officer was brought back to the hospital at the wells in the hollow, the face of the General wore a grave and reserved expression,' wrote Colley's biographer, Lt-Gen Sir William Butler (1899), 'Another old friend had fallen by his side.' With the Boers mustering just below the crestline on the northern face of Majuba, and despite Hamilton's insistence that they be dislodged with a bayonet charge before they were ready to make the assault they were all too evidently planning, Colley even lay down to sleep for a while!

After hours of careful build-up, the Boers launched their main assault on the northern crest of the summit. For Colley and his men, the end came quickly. The British - mainly 92nd Highlanders - were rocked by a devastating close-range volley and seconds later the attackers swarmed over the crestline. (According to Hamilton, the first two of these were black men in European dress). Their panicking opponents were herded into a hollow, their flanks and rear enveloped. Colley's apologists state that he remained 'as cool as on parade' while attempting to steady his men. Hamilton's recollections are more telling, describing a man practically in a state of shock and no longer capable of taking charge of events: 'He appeared to be quite cool and was pacing slowly up and down with his revolver held in his right hand and looking on the ground. He said nothing and appeared to be thinking of things far away'.

The end of a general Pinned down by a ferocious and accurate fire and progressively infiladed on their right flank and rear, the British line suddenly and dramatically collapsed and panic-stricken soldiers, first in twos and threes, and then en masse, broke and fled. Within minutes, they were stampeding down the hillside, but few escaped the lethal fusillade directed against them from the triumphant Boers swarming along the crestline above them. Colley was not amongst them. He had been shot at close range, the bullet passing through the right side of his forehead. Amongst the last of the main British line to begin retiring, it seems that Colley, after taking a few steps, turned around once more to face the enemy, thereby receiving his death wound. He was buried in the military cemetery at Mount Prospect, where so many of his fellow officers already lay interred.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

In his 1931 memoir, Rifleman and Hussar (London 1931, p 55), Philip Marling was respectful but unsentimental in his appraisal of Colley's abilities as a field commander: 'Everybody was sorry about Colley, he was a most lovable person, but his death was a most fortunate thing for him, and as someone said, for the Natal Field Force too'.

It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to defend Colley's poor performance at Majuba. Once on the summit, he effectively abdicated all responsibility, choosing instead to playa waiting game and allowing the Boers to hold the initiative throughout the action. Following his competent, if not particularly brilliant, handling of his troops in the two preceding engagements, this ineptitude is surprising. It lends credence to the theory that Colley was by then in a state of mental and emotional crisis. For the Boers, the First Anglo-Boer War was a memorable triumph over the world's most powerful empire. The failure of George Pomeroy Colley shows the other side of the coin. It encapsulates the poignant tragedy of a brave and fundamentally decent man thrown into a situation beyond his capabilities and paying for it with his reputation and, ultimately, with his life.

Sources

Butler, Lt Gen Sir William, The life of Sir George Pomeroy Colley, KCSI, CS, CMG, 1835-1881 (London, 1899).

Hamilton, Gen Sir lan, 'A Subaltern at Majuba' in Tiger and Sphynx, Vol 3, No 16,20 March 1927, pp 151-4.

Marling, Sir Philip, Rifleman and Hussar (London, 1931).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org