The South African

The South African

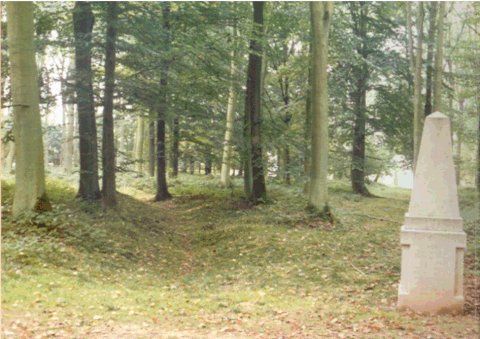

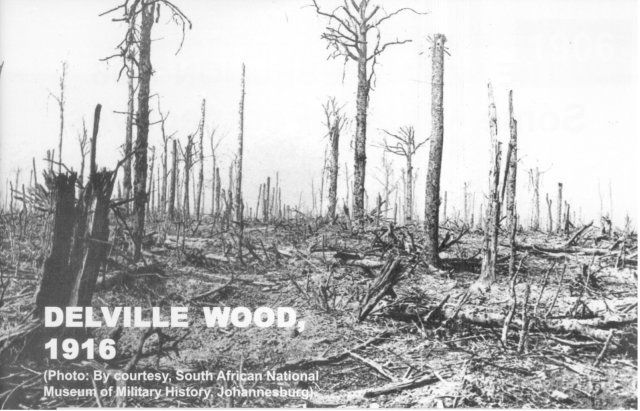

The battlefield of Delville Wood, France, as it appears today [2006]

Ninety years ago, this was the scene of heavy fighting between South African defenders

and the German Army. By the end of the battle, which raged from 15 to 20 July 1916,

only one tree remained. Remnants of the trenches are still visible. (Photo: By Courtesy, SANMMH)

This image was on the inside front cover of this issue

Photos: SANMMH

by Paul Battin, Ottawa, Canada

Constructing a memorial (and later museum) at the site of South Africa's 'bloodiest battle' during the course of Great War, Delville Wood, was, however, as much a political statement as it was a public commemoration for fallen soldiers. Although the memorial at Delville Wood was originally conceived to pay homage to the fallen men of the Union, it served as a political tool. It was designed to celebrate the cooperation of the two white 'races' (English and Afrikaans), united in a common purpose, fighting alongside the Allied forces in the Great War. The commemoration of the fallen took a backseat to politics, however. While commemoration the original purpose of the memorial - should be at the centre of the memorial, a look at the history of the memorial project and the architectural symbolism makes it clear that South African politics were at the heart of this public commemoration.

Background

With the outbreak of war in Europe, South Africa, as a British Dominion, was at war as well. The degree to which she would contribute to the war effort was, however, left to her own discretion. In July 1915, Prime Minister Louis Botha responded to Britain's request to send soldiers overseas by forming a brigade of 5 808 white South African volunteers (Ian Uys, 1993). At the time, it was believed that a brigade would be all that South Africa could raise, owing to the size of the only viable source of soldier grouping available - white males. Each of the four battalions of the brigade was associated with the region where it was formed and from which it drew most of its men - 1st Battalion, Cape Province; 2nd Battalion, Natal, Border and the Orange Free State; 3rd Battalion, Transvaal and Rhodesia; and 4th Battalion, South African Scottish (Ian Uys, 1983, p 1).

Of the total number of men committed to the brigade, only 15% were identified as being of Dutch descent; the rest being English-speaking. Commanded by Brigadier-General H T Lukin, the brigade was composed of well educated, middle-class men who were not part of the Permanent Force of Union Defence, which remained in South Africa to control the unstable political situation there (Uys, 1983, pp 2-3). The South African Brigade arrived in France and formed part of the Somme offensive of July 1, 1916. As part of the advance, they soon found themselves fighting near the French village of Longueval.

During the fight for Delville Wood, at Longueval, the South African casualties were high - 2 536 men out of a total of 3 153 (Bill Nasson, 1997, p293). The site of fierce hand-to-hand combat in heavily forested conditions, Delville Wood became to South Africa what Vimy Ridge became to Canada: a place to assert its identity, no longer as a Dominion of the Crown, but as a force of its own to be recognised on the international stage.

This image was on the Contents page of this issue

The South African Memorial

In early 1919, work began for a memorial to remember those from the Union of South Africa who had fought in service of the Empire during the War. Gen Jan Smuts wrote to the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, expressing his desire to have the remains of South African soldiers who had died in Europe returned to the Union, as a means of commemorating their loss. According to Bill Nasson (2004, pp 57-61 ), it was uncommon for the Imperial authorities to return soldiers' remains to the colonies, consistent with idea of having soldiers of the Empire fighting, dying and resting, shoulder-to-shoulder, with their comrades. Smuts warned that failure to recognise the contributions that white South Africans had made to the Empire would mean that 'the fate of the white race in the Union is going to be very dark. '(Nasson, 2004, p 57).

There had been ceremonies at the site of the Delville Wood offensive in 1917 and 1918, and it had become a popular symbol of identity for the South African Brigade. 'As the high water mark for South African war participation, it [Delville Wood] was trumpeted as a "profound" or "spiritual" legacy of national achievement and sacrifice' (Nasson, 2004, p 62).

Sir Percy FitzPatrick, a wealthy South African industrialist who had lost one son, Nugent, in the Great War, pressed forward and purchased the land for a national memorial from Frenchman Vicomte Dauger for £1 000, later donating it to the government of the Union (Nasson, 2004, p 67). FitzPatrick later became chairman of the memorial committee, touring Europe to raise funds for its construction (J P R Wallis, 1955, p 235).

He approached Herbert Baker (an architect with the Imperial War Graves Commission) to design the memorial which Baker would later describe as 'a special labour of love' (H Baker, 1944, p 90). A personal friend and protege of Sir Cecil Rhodes, Baker had spent time with him in South Africa before the outbreak of war and was therefore familiar with South African / Dutch colonial architecture. These familiarities would serve him well in the design and construction of the memorial. While it may seem that those devoted to the hands-on work of designing and constructing the memorial were doing this as 'labours of love', South African politicians saw in it more than a site of commemoration. Rather, they saw it as a tool to propagate the image of a unified, white South Africa. As Bill Nasson (2004, p 57) notes, 'from its inception, it was envisaged as a spiky political commemoration of Dominion identity and achievement in war, a tracing in granite and marble of the colonial strengths of the South African character across French soil'. This writer agrees with this view. The memorial was used to exploit the sacrifices of South Africans for political purposes in post-1918 South Africa in the hopes of bringing calm to the Union and ending the polarisation of the white population, a precursor to the 1934 Fusion creating the United Party under Smuts and General Hertzog.

Herbert Baker was a proponent of the idea that war memorials were the spirit of a nation. The spirit that he and FitzPatrick, as direct project leaders - and as extensions of other South African politicians following Smuts' lead - wanted to convey, was one of unity. Even though South Africa had been made a Union in 1910, there was still a division between the Afrikaans and English-speaking whites. There was, however, one moment in which they had stood as comrades, not as foes, and that was in July 1916 at Delville Wood.

This idea of 'white unity' can be seen throughout the memorial, a sort of common national history for South Africans, realised in 1926 during the monument's inauguration. Linking the foreign space of Delville Wood to the memory of South Africans would not be easy, however. Baker selected elements of South African architecture to connect the memorial at Longueval in northern France to the Cape.

Unity through architecture

The idea of projecting unity through architecture was not new to him. In designing the Union buildings in Pretoria, Baker had wanted to show the Union of the four colonies in 1910 as well as the 'union' of the two races: Afrikaans and English. To do so, he had constructed the Pretoria buildings in a concave depression (an open air amphitheatre) with 'two high dome-capped towers, symbolising the two races of South Africa' and a 'large low dome, a greater symbol of final union ... a shrine of the great of all [white] races in South Africa' (Baker, 1944, p 60). This same concave depression can be seen in the Delville Wood Memorial, where flanking walls end in two covered buildings that are designed not only to resemble the general form of the Union Buildings, but also to incorporate Dutch architecture found in South Africa, notably the Summer House, built by Simon van der Stel [17th century governor of the Dutch East India Company] on the slopes of Table Mountain above Groote Schuur (Uys, 1983, p 234). Baker even went so far as to restore the vegetation around the memorial using plants native to South Africa, to make the memorial look more 'at home' (Nasson, 2004, p 75).

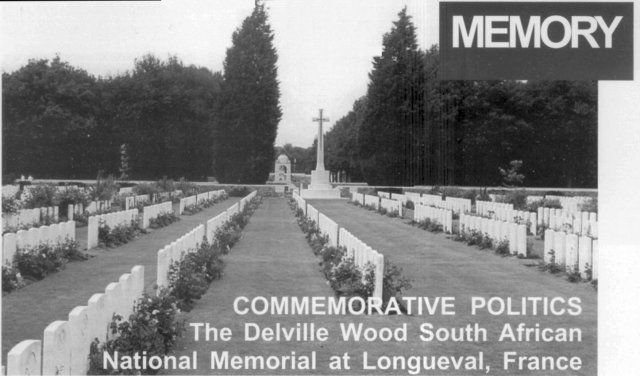

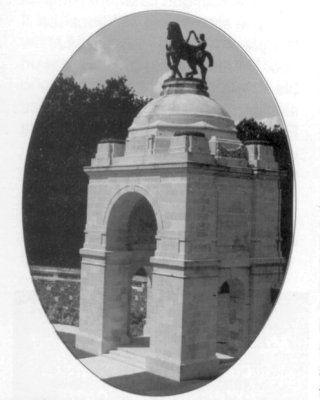

The South African Memorial at Delville Wood,

featuring, above, the representation of brothers

Castor and Pollux controlling a war horse

The stone dome feature at the centre of the Union Buildings in Pretoria was incorporated into the memorial at Delville Wood too, at the point where the two walls meet one another. Atop this massive stone arch is the most obvious political statement of the memorial. Baker had envisioned this space to be filled by a springbok, the mascot of the South African Brigade, but decided that this was not a sufficiently 'heroic' motif. Instead, a bronze statue, depicting two men controlling a 'war horse' rests upon the central arch. Designed by the British artist, Alfred Turner, this statue is a symbolic reference to Thomas Macaulay's poem 'Battle of Lake Regillus', describing twin brethren Castor and Pollux crossing the seas to fight together for the good of Rome (Uys, 1991, p144). For Baker (1944, p 90), it seemed an obvious analogy given the context of the memorial and the South African Brigade: 'Might it not seem miraculous, as the coming of the mythical Brethren did to the Romans, that Dutch and English, such recent enemies, should have come overseas to fight for the British Commonwealth against a common foe?' It is here that the political message of the memorial's original 1926 planners rings the loudest: a bronze statue to show unification of the Dutch and English. (Replicas of the statue would later be erected in Cape Town and at the Union Buildings in Pretoria).

Original inscriptions on the memorial are in English and Afrikaans, another symbol of the unity of the two races that would be put into legislation in 1925, recognising both languages. The inauguration ceremony in 1926 included an Anglican priest as well as a Dutch Free Reformed minister, using religion to symbolise unity and common purpose on the battlefield in 1916 (The Times, 11 October 1926, p 18).

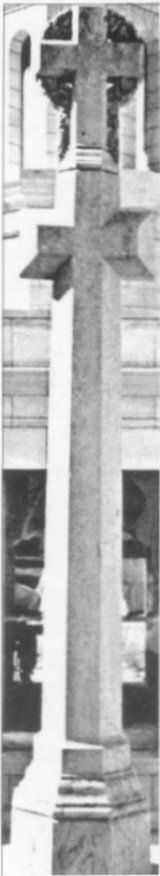

History rewritten

The politics of Jan Smuts and the Union of South Africa during the Great War are not the only ones represented at Delville Wood. The National Party, which gained power in South Africa after the general election of 1948, made their own additions to public commemoration. Between 1948 and 1952, a Voortrekker cross was constructed, bearing witness to the Great Trek of 1836 and the wars fought by the Afrikaners (Boers) against British colonialism and African 'savagery' (Nasson, 2004, p 83). Daniel Malan's Nationalist Party, by adding the cross, had now superseded the original intentions of the memorial - to show unity. Instead, this is an example of an early pro-apartheid government's rewriting of history through a public memorial, emphasising the struggle of the colonial Dutch of the 1830s above that of the South African infantrymen in July 1916.

The Cross

Black participation

While the 'two races' of the Union are represented as the central theme to the memorial, black South Africans are not. Serving mainly in a non-combatant capacity, more than 21 000 black South Africans formed the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) in the First World War (A Grundlingh, 1987, pp 54-5). The SANLC served in France from November 1916 until the end of the war to compensate for a labour shortage in French ports and battlefield infrastructure (B P Willan, 1978, pp 62-4). While the British Imperial War Office welcomed black South Africans (and even requested that the force be increased in size), First World War Unionist policy was much different. With more intermixing taking place between black South Africans and white Frenchmen, Union politicians began to worry about the effect that this would have on the South African social order at the end of the war.

Blacks being seen as equal to whites was exactly what the South African authorities hoped to avoid, accomplished by not allowing blacks to wear a uniform nor allowing them to serve in combat zones in the same capacity as whites. ' ... [I]f black and white were acknowledged to be fighting with and against each other on equal terms this was likely to seriously undermine the future maintenance of the existing state of black/white relationships by devaluing the concept of race as an effective means of forestalling the emergence of class as an alternative, overt, basis for the organisation of social and political relations' writes Willan (1978, P 63). Maintaining the colour bar in South African society remained the highest priority, as reflected in these words quoted by Jason Jingoes in A Chief is a Chief by the People (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1975): "'When you people [blacks] get back to South Africa, don't start thinking that you are whites, just because this place [Europe] has spoiled you. You are black, and will stay black'" (Willan, 1978, p 82). (A similar policy applied to the French colonial empire, which did not consider using black colonial troops until the myth of endless numbers of men in the Empire was dispelled through manpower shortages [C M Andrew et al, 1978, p 14]).

Not only did they serve as a much needed labour force, but black South Africans also played an important part of the South African European war experience. Blackening their faces with soot, white South African soldiers often engaged in Zulu war chants and dances, largely as a method of creating an imaginative haven from which to escape the horrors of war and as primitive intimidation tactics (Nasson, 1997, p 292).

The memory of the SANLC exists on smaller memorials (for example, at Arques-la-Bataille, France, and at Mthatha, South Africa), but there is no mention of them on the Delville Wood South African National Memorial, other than on a bronze bas-relief which displays them as half-naked, disembarking from what appears to be a colonial period vessel. The colour bar policy of the South African government in relation to the SANLC has penetrated public commemoration of the First World War experience at Longueval.

France, too, pays little, if any, recognition to the efforts of its black soldiers (Andrew et al, 1978, p 15). As a national memorial, Delville Wood is pluralistic public history, selective in the individual war experiences it commemorates.

Public memory overseas

Both FitzPatrick and Baker would have preferred to have the national memorial on Union soil, complete with a tomb of an unknown South African in a setting with typical Unionist architecture. However, in selecting the location in northern France, Delville Wood had to be valorised as a place of public memory and commemoration. In placing this national memorial in a foreign country, a new dimension is created in commemoration: 'Il ne s'agit pas seulement de voir que la memoire s'incarne dans les lieux, mais bien de montrer la dimension spatiale de la commemoration. Loin d'etre un simple acte de localisation geographique, la mise en espace est une condition de la commemoration.' (A Hertzog, 2003, p 2, online) In other words, it is in this spatial dimension that the Delville Wood Memorial attempts to legitimise itself as a national memorial which is physically separated from the country it represents.

By transplanting characteristics of South African history and identity into the memorial, it is seen as an extension of South African history in France. This was reaffirmed by the addition of a national military museum to the Delville Wood Memorial complex in 1986. Modelled after the Cape Town Castle, the museum was built around the Voortrekker Cross, previously mentioned, to enhance the modernity of the national memorial in relation to the Second World War and the Korean War. This was the second amendment to the original memorial designed to showcase white unity during the First World War. In the 1986 changes (along with those of 1948), apartheid history has distorted national history. While it would have been an ideal time to include blacks in the national military narrative, their presence in the new museum is almost 'quasi-inexistent', according to Anne Hertzog. Bas-reliefs that show the origins of Afrikaner heritage are more numerous than those showing black heritage (Hertzog, 2003, p 9). This is one of the most recent examples of the Delville Wood Memorial becoming sullied by politics which then distorts the national history narrative.

The message of war memorials

Internal politics has played a major role in the history of the Delville Wood South African National Memorial. From its creation as a monument to commemorate the cooperation of the whites of South Africa, to an assertion ofVoortrekker heritage and finally the contributions of white soldiers in subsequent warfare, political agendas shape its past and design. Jay Winter (1995, p 82) writes that this is the nature of war memorials, often using the deaths of soldiers as a way to advance political messages: 'Commemoration [in 1914-1918] was a political act; it could not be neutral, and war memorials carried political messages from the earliest days of war. .. each nation developed its own language of commemoration .. .' War memorials also had to be 'noble and uplifting and tragic and unendurably sad' (Winter, 1995, p 85). The noble portion of Delville Wood would be the theme of cooperation; the tragic would be the massive loss of life and the exclusive nature of its history. While other nations selected memorials that signified the loss of life, Commonwealth memorials emphasise loss of life and the war itself and how it shaped populations (A Becker et ai, 2000, P 215). The Delville Wood South African National Memorial does indeed show how the white population was brought together (in a physical sense at least) in common action. It also shows the loss of life during a specific battle. It is the explicit statements of white Afrikaner nationalism, however, which have tarnished its original purpose and character, using the memorial politically to shape the national narrative.

This is much different to the original purpose envisioned by individuals such as Percy FitzPatrick, who had lost family members on the Somme. These South Africans, of all backgrounds, wanted a memorial to identify and recognise the final resting place of loved ones, regardless of political imagery. The many changes to the memorial comment not only a great deal about politicians' aims to dictate the history of South Africa, but also their wish to sculpt South African identity. As John Gillis (1994) writes, just as the memorial has been changed to reflect the history (selective as it might be) of the South African forces in the First World War, South African identity will change as well:

'That identities and memories change overtime tends to be obscured by the fact that we too often refer to both as if they had the status of material objects memory as something to be retrieved, identity as something that can be lost as well as found. We need to be reminded that memories and identities are not fixed things, but representations or constructions of reality, subjective rather than objective.'

Conclusion

The Delville Wood South African National Memorial at Longueval was designed with a twofold motive in mind. Originally conceived as a monument to commemorate the fallen South African soldiers of the First World War, it also serves as a means of reflecting South Africa's dominant internal and competing political ideologies through time, a political motive which overshadows the former. Even though it is located within another sovereign state, the symbols used both in its original form and in its subsequent alterations, leaves no doubt about its connection to the South African state. Architectural designs familiar to South Africa define it as a piece of South Africa in France, as national soil in a foreign land. Tampering with its original design and purpose by the ruling parties of South Africa, has turned the memorial into a statement of apartheid philosophy, hiding behind the veil of commemoration as a public monument and interpretive centre. By looking at Delville Wood with a critical eye, it is clear that these deliberate' assertions overshadow its original commemorative nature. Instead, it is the history of exclusionist apartheid policies and their impact on a divided population and its public history that is commemorated.

Sources

Audoin-Rouzeau, S and Becker, A, 14-18, Retrouver la guerre (Editions Gallimard, 2000).

Andrew, C M and Kanya-Forstner, A S, 'France, Africa, and the First World War' in The Journal of African History 19(1), 1978, pp 11-23.

Baker, H, Architecture and Personalities (London, Country Life Ltd, 1944).

Becker, A, La guerre et la foi: De la mort a la memoire, 1914-1930 (Armand Colin, 1994).

Buchan, J, History of the South African Forces in France (New York, Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd, 1920).

Cave, N, Delville Wood (South Yorkshire, Leo Cooper, 1999).

Garson, N G, 'South Africa and World War I' in The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 8(1), 1979, pp 68-85.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org