The South African

The South African

The March to Modder River

Introduction

Gilmerton House, the home of the Kinloch family, nestles gently into the East Lothian landscape, adjacent to Haddington, Athelstaneford and North Berwick, in Scotland. The Kinlochs were originally wealthy merchants from Edinburgh and Francis Kinloch, Lord Provost of Edinburgh, purchased Gilmerton House, East Lothian, in 1655. He was knighted in 1686 for lending £300 to James, Duke of York. Thus was founded the Kinloch Nova Scotia Baronetcy of Gilmerton. There were originally 329 such titles awarded. Today, only about one hundred remain (see note).

The following account of the peculiar proceedings which followed the return to Britain from South Africa of a distinguished soldier, Lt Col David Kinloch, 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, is the story of the heir to that title. It was only through a careful study of the letters, photographs, documents and diaries of the key players, hitherto lying undiscovered in the Kinloch Archives at Gilmerton House, East Lothian, that some inkling of the political, social and economic forces behind the curious treatment of this soldier could be revealed. The Kinloch Archives are in the hands of the present Sir David Kinloch and the Trustees, who gave permission for this initial research to be carried out.

The questions

Many questions are raised by the extraordinary events that unfolded. Kinloch was a distinguished leader in the Anglo-Boer War who saw action at many of the premier battlefields. He was with Lord Methuen in his advance towards Kimberley. He was also at Poplar Grove and Driefontein, during the operations which preceded the occupation of Bloemfontein by Lord Roberts. What, then, was the social and historical context of Field Marshal Lord Frederick Sleigh Roberts' decision to relegate him to half-pay? What were the social circumstances that precipitated the involvement of the King, the Prime Minister and both Houses of Parliament in this matter? Why did Kinloch's Court of Enquiry have such profound repercussions for the Government and why was the inalienable power of the British military organisation brought into question? Why did this case become a matter of such public controversy? What was the power in the interconnectedness of influences that prevailed? These are questions that demand some kind of answer.

Kinloch in South Africa

Kinloch, born on 20 February 1856, eldest son of the 10th Baronet, was educated at Eton and at University College, Oxford, before being gazetted as second lieutenant in the 96th Foot in May 1878. He was promoted to lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards in July 1881. From April 1885, to April 1890, he was adjutant of the 1st Bn, Grenadier Guards, getting his captaincy in October, 1889. He ).. was promoted to major in September ~. 1894. In 1897, he married Elinor 'Nell' Lucy, daughter of the late Col W Bromley Davenport, Member of Parliament for Cheshire, and sister of his son of the same name, also an MP, who was to figure significantly in what was to be called the 'Kinloch Affair'. When the Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899, Kinloch went to South Africa as second-in-command of the 3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards.

The young David Kinloch, as a student at Eton

A decorated soldier

In 1900, Lieutenant-Colonel Kinloch returned to Britain to command the 1 st Battalion, having been promoted to fill this vacancy in January, 1900. He was Mentioned in Despatches and was created Commander of the Bath for his services in the field. In March 1901, he was made a Member of the Victorian Order. Kinloch's period of active service is lavishly illustrated in his field diary, his letters to his wife, his photographs and his drawings. His military records show him to have been exemplary in his bravery and much loved by those under his command.

After months of active engagement in South Africa, David Kinloch, recalled to take command of the 1 st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, at Wellington Barracks, was coming home to his wife and family. On Wednesday, 2 May 1900, his wife wrote jubilantly in her diary:

'My David is coming back! He is on the sea! He sailed today. I can't believe it, coming back, coming home safe. Neither killed nor maimed nor invalided! It seems too good to be true. I have never had anything so delightful to look forward to. I am feeling rather rested. I think of what Lady Raglan said to me:

"Remember, dear Nelly, joy tires as much as sorrow does", but I don't think so; at least, I don't feel it yet.'

But neither Kinloch nor his wife were to know that this homecoming, which was to be so celebrated, was only the beginning of what would emerge in the year ahead as a reflection of a nation riddled with political and social intrigue, wallowing in the guilt of what had probably been the most significant military fiasco of all time.

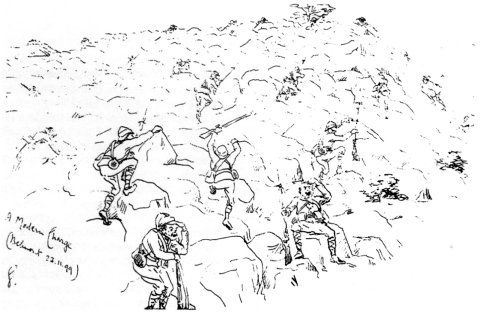

A wartime sketch by Lt Col D A Kinloch,

Grenadier Guards, showing the battle of Belmont

The complaint

In December 1902, three peers, the Duke of Wellington, Lord Belhaven and Stenton and Lord de Saumarez, each a relative of a subaltern in the 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, sought an interview with Lord Roberts, then Commander-in-Chief, in order to complain that young officers of the battalion had been tried by subalterns court-martial for minor military offences as well as for social transgressions, and that sentences of punishment had been passed and carried out.

The irregularity of such practices was manifest, and although it was later established that Lieutenant-Colonel Kinloch had known nothing of these occurrences within his battalion, he was placed on half-pay in February 1903. He did not lack defenders, and his case became a matter of national and public controversy.

What, then, prompted Lord Roberts to initiate the action that he did - of suspending Lt Col Kinloch on half pay? What could have justified this almost unprecedented interference in regimental custom? The answers lie in the Court of Enquiry, the key actors in the drama, and the proceedings which followed. It was a matter of public sentiment and political action which resulted in the involvment of the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the Prime Minister, A J Balfour, and King Edward VII himself.

The scandal

The story first broke early on 17 January 1903, in The Onlooker. Four days later, The Sun gave more substance to this brief mention by specifying a case of 'ragging', or beating, in a 'well-known regiment of the Guards'. So strong was the complaint that Lord Roberts took immediate action by requesting the commanding officer, Lt Col Kinloch, to 'send in his papers'. The three young officers who had been ragged were the Marquis of Douro, the Master of Belhaven and Mr J H Levison-Gower. Their fathers, respectively, were the Duke of Wellington and Lord Belhaven and Stenton, with Lord de Saumarez being the uncle of Levison-Gower. The Lords of Belhaven and Stenton are both names of places adjacent to Gilmerton, the ancestral home of the Kinlochs.

What had been happening in the battalion was a series of subalterns' courts martial in which various young officers were punished for minor infringements such as courting an actress, visiting a hairdresser in uniform, and walking down the Strand in a boater. The punishment that had been meted out to them included being beaten on the bare buttocks by up to twenty fellow officers. On at least one occasion, blood had been drawn and the victim had fainted. Earlier, two little Drummer Boys had been flogged for smoking (Broad Arrow, 28 March 2002). Kinloch, who had been in command at the time, was unaware of the floggings. There was also an extremely unpleasant case of the brutal treatment of a certain Mr Stanford at the Mount Nelson Hotel in Cape Town (The Truth, 2 July 1903, pp 22-4). (In this case, the officers involved eventually agreed to pay £1 500 in damages, and to make an ample apology, which Mr Stanford accepted, although the charge of indecency made by him against them was not withdrawn).

The aristocratic component in this elite regiment was considerable and, as has been noted above, in this particular instance the relatives were extremely influential individuals with high social status. They used this status to personally call on Lord Roberts to air their grievances. Their sons had been charged with refusing 'to ent3r into any of the amusements and sports of the regiment' and their fellow subalterns, determined to 'stop such rot', held the mock trial and found them guilty 'of belonging to the most noble and respected families in the Kingdom, and failing to report themselves as consummate asses.' Corporal punishment was duly meted out in what was known as 'bullying' or 'whipping'. Lord Belhaven drafted the letter to Lord Roberts in which 'he accused Colonel Kinloch of being absolutely unfit to command any regiment, and asked for his dismissal'. At the same time, the mother of one of the aggrieved young officers complained to the wife of a distinguished officer who then passed it on to Lord Roberts.

Lord Roberts wrote immediately to Kinloch, requesting that he forward his papers, but also enclosing a private note in which he intimated that he felt that Lt-Col Kinloch was not culpable and that he was totally exonerated from all blame in the affair.

The reaction

The officers of the Brigade of Guards, together with Kinloch, reacted angrily to the apparent contradiction of the two items and Kinloch refused to send in his papers. Together with two fellow senior officers, Colonel Horatio Ricardo, commanding the Home District, and Major-General Oliphant, Kinloch went to see Roberts and a heated argument took place, but the latter was adamant that his decision was final. It was now quite clear, at least from the point of view of Kinloch and his rapidly growing band of supporters - many of whom were later to emerge as politically and economically powerful - that both the Duke of Wellington and Lord Roberts had committed a gross breach of military etiquette.

The Army, as a whole, was totally in Kinloch's favour. Having failed to obtain satisfaction from Lord Roberts, Kinloch eventually laid the matter before his friend, King Edward VII. Roberts refused to be persuaded by the King to let the matter drop and said that if Kinloch retained his position then Roberts himself would tender his resignation.

Other events of a personal nature now began to intrude. David Kinloch's brother, Major Harry Kinloch, became seriously ill, and his father, Sir Alexander Kinloch, had come from Gilmerton House in East Lothian to be in London with his son . Harry died on 20 February 1903. In addition, the relationship between David Kinloch and his wife began to feel the strain and, in September 1902, their son, David Alexander Kinloch, had been born. In the midst of this turmoil, on what was a very emotional occasion on 4 February, David Kinloch visited Aldershot to take final leave of his battalion. According to the Daily Mail, he met with a remarkably enthusiastic reception.

The Grenadiers were to have a new colonel, but the matter did not end there. The senior subaltern, Lieutenant Swaine, who had also served in the AngloBoer War with outstanding gallantry, was to lose a year's seniority. Like Kinloch, he had had no knowledge of the alleged 'ragging' or thrashing until it was all over but, as in all regiments, he was held responsible for the behaviour of his subordinates. The resignation, on the same day, of Sub-Lieutenant C L Blundell Hillinshed-Blundell, who had been gazetted, at the same time as Kinloch, was not, apparently, connected with this matter, but the consequences of the affair were beginning to look very serious nonetheless. It seemed possible that this debacle, following as it did another scandal in the 1st Life Guards, would result in an entire revision of the privileges enjoyed by the Household Troops in managing their own affairs.

David Kinloch, London, 1899

The other scandal

An earlier scandal in the Grenadiers, in July 1890, had erupted after the 2nd Battalion had 'refused duty', the direct result of excessive guard duties and inspections ordered by Col Mackgill-Crichton-Maitland in addition to their normal duties. When the bugle had sounded the 'Fall-In', only a few men had complied. Although this event had never been described as a mutiny, it had sufficiently shaken the War Office for orders to be given (though these were later countermanded) that the Royallnniskilling Fusiliers were to be moved from Portsmouth to London. The Yorkshire Regiment (the old 19th Foot, and later the Green Howards) were sent instead. Even so, this incident, involving disobedience, has to be seen in the context of the time. The late nineteenth century saw several significant civil disruptions, including the Bryant and May's 'Match Girls' strike of 1888, followed by the 'Dockers Tanner' strike of 1889 and the 1890 strike by London Post Office workers. There was even widespread discontent among the Metropolitan Police who threatened industrial action. In this context, many viewed the 2nd Grenadier Guards' 'refusal' to perform their duties, in July 1890, as tantamount to revolution.

After the fiasco of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), the British military was more than a little sensitive to public opinion. The tide of opinion against Lord Roberts did not improve with his disastrous handling of the Kinloch case. The talk in military circles of Kinloch's summary dismissal was electrifying. Here was a man of exemplary character, courage and decency, well-liked by his men and decorated, but who was now seemingly being made a scapegoat for something about which he had no previous knowledge.

The political and social influence brought to bear by the three peers of the realm was beginning to be seen as a gross intrusion into the traditional autonomy of the regiments of the British Army. In the Guards' Club on the evening of 4 February 1903, therefore, not a voice was raised in defence of the War Office. Every officer present seemed to be convinced that injustice had been done and one distinguished soldier was even heard to ask for 'more social influence!' Not surprisingly, it soon emerged that Kinloch, too, had friends in high places.

Not only had King Edward VII intervened directly in the affair on behalf of Lt Col Kinloch, but Kinloch's highly influential brother-in-law, Bromley Davenport, was the first to raise the question in the House of Commons. The House of Lords soon joined in and some of the most illustrious peers in the land lent their support to Kinloch. Lord Esher, who had been one of Victoria's 'inner circle' at Windsor Castle, also brought his not inconsiderable influence to bear. The Conservative prime minister, Balfour, not only a close friend of Kinloch since his Eton days, but also his neighbour (having been born and brought up in Whittinghame, in close proximity to Gilmerton House) also wanted to intervene on behalf of his friend. However, because of his important position, Balfour was unable to do so.

The political and moral effects of the war

The war in South Africa, from 1899 to 1902 had been an expensive victory for Imperialism. In a very real sense, it had displayed the inadequacies of British defence planning and the fact that the War Office was still entrenched in nineteenth century military thinking.

Against this background, what conclusions can be drawn from the so-called 'Kinloch Affair'? The political and social shenanigans that had been witnessed, especially in regard to the actions of the three peers, were viewed by many as a gross intrusion into and an erosion of the traditional autonomy enjoyed by the British Army. Lord Roberts' popularity had lessened, particularly as many officers and privates viewed his treatment of Kinloch as unduly harsh. It galled them that their Lord Roberts appeared to be susceptible to the influences of social class.

What the 'Kinloch Affair' also brought to the fore was the reality of the serious divisions within the upper echelons of the British military organisation. There were three distinct factions, comprising Lord Wolseley's 'British school', Lord Kitchener's 'Egyptian school' and Lord Roberts' 'Indian school' and they were intensely jealous of each other. British military shortcomings in South Africa at the time were attributed to these divisions. Wolseley had his 'Staff ring' or band offavourite officers, Cecil John Rhodes his 'Lambs', Kitchener his 'Cubs' or 'family of boys', and Lord Milner his South African 'Kindergarten'. Such divisions were likely to have disastrous effects.

Of course, when Lt Col Kinloch had been recalled to England in 1900, the war in South Africa was by no means over. In spite of British expectations, it did not end at the end of 1900 either. Instead, the British occupation of the two Boer republics led to the opening of guerilla warfare that would not cease until the end of May 1902. Thus, many felt that the honours bestowed upon Lord Roberts in 1900 had been awarded prematurely.

Brodrick's handling of the War Office was also heavily criticised. Many perceived that justice was being withheld from many deserving officers in the field, while recruiting figures were in decline and over 7 000 soldiers were in prison.

Erosion of the aristocracy

It also needs to be noted that the British aristocracy in the nineteenth century comprised a relatively small coterie of incredibly wealthy and powerful families. Within the space of a hundred years, these families had lost much of their power, wealth and prestige. The majority of aristocrats had country seats while they also had houses in London. The Kinlochs, for example, had, in addition to Gilmerton House, their London houses in Eaton and Belgravia. War decimated the aristocracy, however, and the Anglo-Boer War saw a disproportionate number of sons from titled families being killed. In the Guards regiments alone, the cost in aristocratic blood was enormous.

After the Kinloch Affair

Eventually, after four harrowing months in a country steeped in military and political intrigue, Lt Col Kinloch was vindicated and all his privileges were restored. In February 1904, he was given the brevet of colonel and in June 1906, he went on retired pay. He commanded the 6th Brigade of the 2nd London Division, Territorial Force, from 1908 to 1912, and in the latter year he succeeded his father in the Baronetcy of Nova Scotia.

At the outbreak of the First World War (1914-1918) Kinloch was appointed to the 70th Brigade of the 23rd Division of Kitchener's New Armies. He took his brigade to France, but relinquished command in September 1915, and was Mentioned in Despatches. In 1917, he was gazetted honorary brigadier-general. He was a member of the Royal Company of Archers (King's [sic] Bodyguard for Scotland), and he was a director of Leslie and Godwin, Limited, insurance brokers. He was the first man, together with Lord Balfour, to play golf in Ireland, and when he introduced the game to Oxford, people mistakenly thought he was practising hockey!

Sir David Kinloch died in 1944 and lies buried in the cemetery at Athelstaneford churchyard, the site where the first glimpse of the Saltire is traditionally said to have appeared in the sky in 832 AD.

About the author

Dr Kenneth Jones, BA (Hons), ACE, Dip Theol, PhD, FRSA, FCollP is a Specialist Tutor with the Open University and a tutor at the National Extension College, Cambridge. He was formerly Professor of Sociology at the Universities of Botswana, Athabasca University, Canada, and the University of Transkei, and lately Medical Sociologist, Queen Margaret University College, Edinburgh.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org