The South African

The South African

Amalinde

The exact site of the battle of Amalinde remains uncertain. It seems unlikely to have been literally on the Amalinde. The old isiXhosa word, i-linde or umlinde, means 'grave mound and/or furrow', hence the descriptive name, Amalinde, used to describe many of them (Kropf, 1915, p 217). No armed force would willingly choose to fight in veld covered by these features. The Amalinde mounds are up to a metre in height and the hollows between them are inconsistent in depth and size, too large to jump over. There is no level ground anywhere. The mounds are also usually covered by worm casts up to 10cm high with a mass of anything up to 800g. The Amalinde mounds and hollows are formed by the activity of giant earthworms (Microcheatis) in the waterlogged conditions occurring there during wet weather. Using their enormous casts, these large worms build up these mounds and retreat into them to avoid becoming soaked. The sodden conditions occur as a result of an impervious underlying rock layer which is also resistant to subaerial erosion (Kopke, 1980, pp 146-55). Men running barefooted over these micro landforms could only do so with the greatest of difficulty, so fighting here would not be by choice. And, yet, the evidence suggests thatthe terrain over which the battle of Amalinde was fought had indeed been chosen in advance. Ndlambe's strategy was that he reputedly stationed his young and inexperienced warriors in the open to serve as bait to draw out his arch-rival, Ngqika. His older and more experienced warriors were hidden and only came into action later after Ngqika's force was scattered and tired after the first encounters with the young warriors (Bokwe, 1914, pp 21-22).

Ngqika's approach

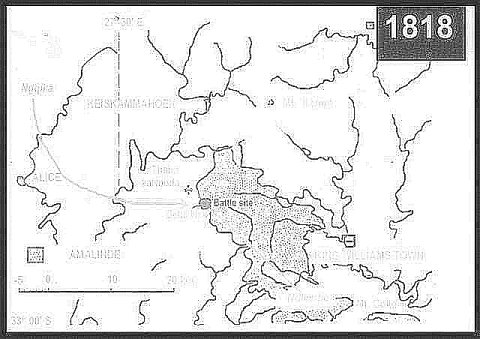

Most sources state that Ngqika and his men proceeded to Debe, the River Valley, the Debe Flats, or the Amalinde-covered area in particular - the hollows are also known as indebe, meaning 'pock mark' or 'a ladle' in isiXhosa (Brownlee, 1896, p 340; Mostert, 1992, pp465-6; Soga, c1931, p 165; Thompson, 1967-8, etc). Air and satellite images of the area in question show the upper portion of the Debe River as a valley which could be described as a ladle-shaped hollow, which may be the origin of the name.

Before the battle, Ngqika would have followed a route that skirted the foothills of the Amathole - the route followed by the roads and railway today. Thus he only arrived at the battlefield at noon, having traveled some 45km that morning. By examining the area and possible sites, it becomes evident that the only cover afforded to warriors was the thatching grass that abounds in the area even today. It is said that Ngqika watched the battle from the hillside, possibly even on the foothills of the Thaba KaNdoda range that flank the Debe River valley to the north (Brownlee, 1896, p 340).

Ndlambe's route

Having the shorter distance to travel to the battle site, it seems probable that Ndlambe would have selected an area which held the greater advantage for him. At the time, Ndlambe's 'great place' was at Mount Coke, only some 25km away from the Debe Nek.

One view with regard to the possible location of the site of the battle of the Amalinde is that, to arrive at the battle site, the Ndlambe had to cross a large area covered by the Amalinde (see dotted area on the map) and therefore, for these warriors, it really was the battle of the Amalinde. One could speculate that they may have waited in ambush in the nek or pass known as Debe Nek, a gap through which Ngqika's forces would have had to pass in order to proceed further to the east in the direction of the enemy's stronghold at Mount Coke. At this nek, the Ndlambe would have found shelter in the thatch grass that covers the area and, because the nek lies slightly higher than the plain of the Debe River to the west, this position would have afforded Ndlambe the added advantage of looking down on the Ngqika warriors. The Nek also marks the abrupt end of the Amalinde covered area as the Debe River makes its way eastward by headward erosion into the level land to the east, giving rise to the nek.

The Ndlambe may thus conceivably have set their trap and exposed their young warriors on the smooth plain of the Debe River while the older, more experienced warriors waited above in the Amalinde, concealed in the hollows and by the metre-high thatch grass that grows there. Given this scenario, the Ngqika warriors would have proceeded east from British Ridge across the Debe flats towards Debe Nek, quite unaware that they were about to be ambushed. Their first sighting of the young Ndlambe warriors would presumably have occurred as they crested the rise where the old Fort White was later built. From there, the upper portion of the Debe Valley is clearly visible up the Nek. Ngqika himself could then have gone uphill to his left while his warriors dealt with the young Ndlambe warriors, whom they outnumbered. 'Today, we have them', one of Ngqika's councillors is reputed to have commented (Mostert, 1992, p 466).

Into the hollow

According to J H Soga, the warriors of Ngqika then proceeded to the Debe Valley (Soga, c1931, p 165). Considering the isiXhosa meaning of the word, this whole area could be considered as a hollow, ladleshaped valley surrounded on all sides by higher ground. There are, however, also other areas in the vicinity with the same characteristics, also with Amalinde, which fit the description of the battlefield. One possibility is the upper valley of the Ngqeqe River which runs due north from Thaba KaNdoda to the valley of the Rabula River. A place name for a col, KwaMakabalekile, holds a further clue in support of the theory that the Debe Valley was the site of the battle. This place name is derived from the word baleka, meaning 'to run'. After the battle, the defeated Ngqika would have run away and this place name suggests the direction in which they ran. The steep route thus indicated leads directly to Burnshill, the site of Ngqika's 'great place' a decade earlier, where the Batavians had visited him in 1803. In 1828, the Rev Laing established the Burnshill Mission there when Ngqika was once again living in the area and where he died and was buried in 1829.

Fires

The matter of the bonfires can also help to give an idea of where the site of the battle was likely to have been. Sources mention large bonfires having been lit as the sun went down so that the wounded, in hiding, could be found by firelight and dispatched. This probably meant that the thatch grass was set ablaze; indigenous bush never burns although the fringes are kept intact by fire that regularly burns the surrounding old grass. The cold weather is also mentioned, possibly indicating a late cold front in October with rain and possibly even snow, which would have made fire-lighting without the aid of matches or tinderboxes almost impossible. It would thus seem that the Ndlambe came prepared for this eventuality, bringing burning coals in clay containers to the battle. This would have enabled them to set fire to the grass, but not to the bush. With the grass alight, the Ndlambe would have been able to pick out the Ngqika wounded, who would have tried to escape the flames.

Did the terrain suit fire-lighting? Bonfires would, at best, light up an area 100m across and would have required large quantities of wood. Couzens (2004, p 70) also suggests that an ambush in rainy conditions would seem more plausible than in bright sunshine. These clues would cast doubt on the site pointed out to him by the headman - this area did not have high ground nearby from which Ngqika could have watched the proceedings; neither is it near to material which could be used to fuel a bonfire in drizzle.

The number of warriors

How many warriors were involved in the action? By all accounts, the warriors of the Ndlambe outnumbered those of the Ngqika. In traditional Xhosa warfare, it was unusual for large numbers to be killed. Engagements were usually short and involved only limited numbers of warriors. Also, most wars were fought over political supremacy and victory was easily worked out by counting the number of cattle captured. The desire to eliminate the enemy was alien (Mostert, 1992, p 466; and Peires, 1987, pp 138-45, giving an overview of Xhosa battle tactics).

The battle of Amalinde appears to have been an exception. Fighting was particularly fierce and the enemy was ruthlessly pursued and killed. Several authors refer to massacres and the 'routing of the enemy'. According to Soga (c1931, p 165), Xhosa tradition held that 500 Ngqika warriors were killed during the battle. If one takes this as a base, bearing in mind the exceptional nature ofthe battle and assuming a 10% kill rate, the total number of warriors could add up to as many as 5 000! Since Ndlambe was assisted by his Transkei allies and it is generally held that his troops substantially outnumbered those of Ngqika, one could imagine up to 10 000 Ndlambe warriors involved at a ratio of 2: 1 to the enemy. These figures broadly correspond to those quoted by Peires, based on reports from Dr van der Kemp, Lichtenstein and Colonel Collins who undertook an inspection tour of the Eastern Frontier in 1809. Though these figures remain estimates only, they do seem to indicate that, in 1800, the Xhosa population was well below 100 000 and might even have been as low as 40 000 (Peires, 1987, pp 2-3). Eighteen years later, it would therefore have been quite possible for Ndlambe and Ngqika to muster forces of about 5 000 men.

Bibliography

Bokwe, J K, Ntsikana (Lovedale, 1914).

Brownlee, C, Reminiscences of Kaffir life and history (Lovedale, 1896).

Couzens, T, Battles of South Africa (Claremont, 2004).

Kopke, D, 'Debe Hollows of the Eastern Cape' in Fort Hare Papers, Vol 7 No 2, 1980.

Kropf, A, A Xhosa English Dictionary (Lovedale, 1915).

Milton, J, The edges of war (Cape Town, 1983).

Mostert, N, Frontiers (London, 1992).

Peires, J B, The House of Phalo (Johannesburg, 1987).

Soga, J H, The AmaXhosa: Life and Customs (Lovedale, c1931).

Thompson, G, Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa (Cape Town, 1967-8, reprint).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org