The South African

The South African

by Emrys Wynn Jones

United Kingdom

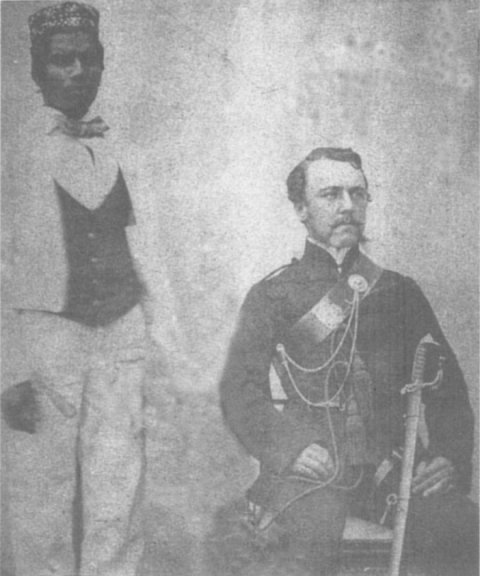

Ensign Benjamin Simner in Poona, December 1858.

Inscribed: 'My dear Parents - I send you this in

commemoration of my twenty-first birthday'

(Reproduced by kind permission of Mrs Wendy Roderick,

Simner's great-great-granddaughter).

At the end of the Crimean War, the British Government had to wrestle with the future employment of the members of the foreign legions raised to provide seasoned troops for the Crimea but never used in action. A scheme was devised to send former legionaries to the Cape as Military Settlers and, in Part 2, their progress there was followed and their performance assessed. When the Indian Mutiny broke out, reinforcements were urgently required, and a contingent of about 1 000 of the Military Settlers departed for India towards the end of 1858. Ensign Benjamin Simner accompanied the Military Settlers to the Cape, and was one of the volunteers who later went to India.

The first detachment of German volunteers, consisting of nine officers (one of whom was Ensign Simner) and 320 NCOs and other ranks, sailed for India in the steamer Prince Arthur in October, arriving in Bombay on 8 November 1858. According to the Bombay Standard for 9 November and 13 and 20 December 1858, further drafts arrived aboard the sailing vessels Ariel, Estafette and Edward Oliver on 10, 11 and 18 December respectively and, as they disembarked, each detachment was sent by train to Poona (now Pune). By Christmas, the German Volunteer Battalion (one of several names by which it was to be known) was fully assembled there, its total strength being thirty officers and 1 038 NCOs and men. (Lists of officers who landed at Bombay appeared in the Bombay Standard and, with allowance for vagaries of spelling, correlate well with the Nominal Roll of officers selected to go to India in OIOC, Military Consultations India, P/48/51, pp 28-9, and with the Army List for July 1856). Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Somerset, commanding the Bombay Army, was complimentary, saying: 'These Germans are a very fine body of men ... will shortly be ready to take the field' (OIOC, P/48/ 56, Letter No 197, Lt Gen Sir H Somerset to Adjutant General, India, 23 December 1858).

Ensign Simner in Poona

Benjamin's travels at this point can be traced through his father's list of letters, which records that he left East London on 18 October and arrived at Bombay on 8 November. Within days, he was in Poona and it was from there that, on 21 December, he sent his parents a photograph of himself in military dress to mark his 21 st birthday. It was in Poona too, that he began his lifelong association with freemasonry, his initiation taking place on 13 December at St Andrew's-in-the-East, a Lodge chartered in 1844 that was part of Scottish freemasonry, and which still exists (Simner Family Papers). His service record for this period relates his experience with remarkable brevity:

The Jager Corps

Wooldridge was intent on keeping his regiment in existence and, on 22 December, wrote to the DAG at Poona, requesting additional German-speaking officers and seeking clarification of the prospects of his existing officers (OIOC, P/48/56, Wooldridge to Deputy Adjutant General, HM's Forces, Poona, 22 December 1858). In his view, none of his subalterns (that is, all but six of his combatant officers) had sufficient experience to be promoted to command companies and, instead, he requested experienced officers of Queen's or Company regiments who could speak German. Failing that, he suggested that captains from the German Military Settlers still at the Cape, or even members of the original Legion, be applied for. At that rate, it was going to be some considerable time before they were ready for action.

The arrival of Major E J Ellerman, an experienced officer of the 98th Regiment, who had served as AAG of the Legion and was present at its disbandment in Colchester, met in part Wooldridge's request for seasoned officers (OIOC, L/MIL/17/4/429, p44, 3 March 1859 [re: posting to GVB], p 205, 13 December 1859 [command of detachment for the Cape], and the Army List generally). He sailed for India in October 1857 and, in 1858, served in the Peshawar Expeditionary Force under Brigadier Sydney Cotton. When the Jager Corps was disbanded in India, he was placed in command of the party returning to the Cape, including men of the Corps who were undergoing punishment in the House of Correction.

Wooldridge also requested that the regiment be styled 'the Jager Corps', arguing that the term 'German Volunteer Battalion' was a misnomer (OIOC, P/48/56, Wooldridge to Deputy Adjutant General, HM's Troops, Poona, 26 December 1858). About 240 ofthe men had formerly served in Jager regiments and the remainder, with the exception of 56 cavalrymen, in the light infantry. What was more, the uniform already authorised for them, black or green, was in the authentic Jager style. The regiment continued to be referred to loosely by a variety of names, but when they were disbanded the order contained the words 'the late Jager Corps', giving Wooldridge the small satisfaction of having had the last word.

Somerset seemed at a loss to know how to deal with this barrage, saying rather plaintively to the Adjutant General: 'The only information I have relative to these men is contained in two letters ... from Sir George Grey, the Governor at the Cape of Good Hope' (OIOC, P/48/56, Lt Gen Sir H Somerset to Adjutant General, HM's Forces, India, 23 December 1858). While Wooldridge's proposals were being considered by the authorities, a letter arrived from the Secretary of State for India, the tenor of which, said the Secretary to the Government of India, 'rendered it unnecessary to pursue them further'. The letter from East India House revealed a marked aversion to keeping together 'a corps of foreigners with its officers, and [in] assigning to the latter a proper position in the armies of the three Presidencies'. It preferred a solution similar to that previously suggested by Grey, namely that any officer not required in India should be sent back to the Cape, and that the men should be 'drafted in suitable proportions to the several existing corps of European artillery, cavalry and infantry of Bengal, Madras and Bombay' (OIOC, L/MIL/3/2224, Secretary of State for India to the Governor General of India, 19 January 1859). Evidently, there was to be no separate identity for the Germans in the new Indian Army. As will be seen, the order was, in due course, carried out, but for some months the Jager Corps continued its anomalous existence, waiting for the axe to fall. There were rumours that it was to remain at Poona and, on 13 December 1858, The Bombay Standard reported that 'the German Legion stand fast for some time to come'.

Arrival of the Germans

Given the events of 1857 and 1858 it was not surprising that the arrival of the Germans excited comment in Bombay, the tone and content of which mirrored the debate that had taken place at home when they had been formed. An article in The Bombay Standard on 11 November 1858 spoke of a new era in which strangers were to be incorporated into the army for the first time. They came, said the Standard, under very exceptional circumstances, which it proceeded to discuss at length, demonstrating in so doing that the Legion's blemished reputation had preceded it. Its members, declared the Standard sweepingly, 'had been recruited from the idle and discontented of German Society', and were 'the worst colonists it was possible to find'. Having delivered this unflattering judgement, the writer mellowed, conceding that 'we cannot see why the ranks of the British army in India should not be swelled by mercenaries', and comparing them favourably with 'the Indian troops like those which the Presidency of Bengal has boasted of far half a century'. (Most of the regiments that mutinied belonged to the Bengal Army.) However, the armchair expert of the Standard advised that care should be taken to ensure that the Germans never outnumbered the British troops in India (The Bombay Standard, 11 November 1858, p 916). There was no danger of that.

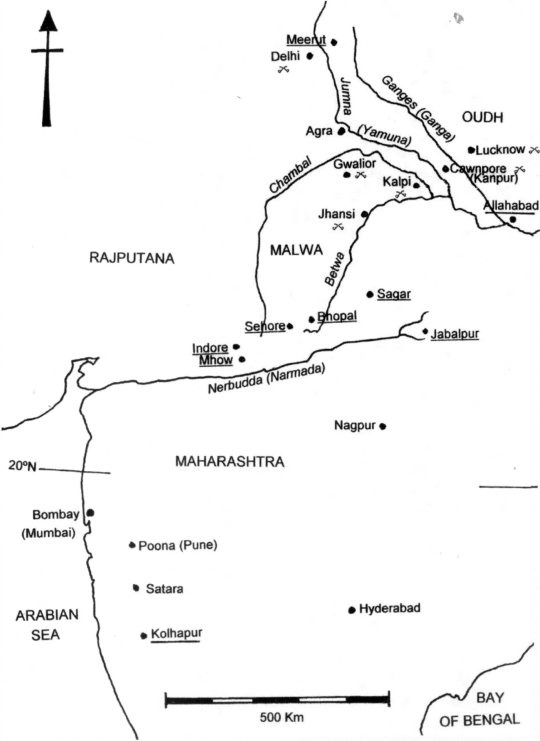

Map: Northern India during the Indian Mutiny, 1857-9, showing the sites

of major engagements and other towns where mutinies took place (underlined).

The German Choristers

The arrival of the Jagers in Poona was welcomed not only for the accession to military strength that they represented, but also for the new dimension that they brought to social and cultural life. The Bombay Standard (3 December 1858, p 1083) reported that 'the choristers of the German Legion (Gesang Verein) delighted lovers of harmony at Poona with an outdoor entertainment at the Ghorpoorie Bandstand on Saturday last, when they sang some of their sweetest melodies'. Ten days later, during a performance at the Station Theatre, some of the German volunteers 'poured in a strain of delightful melody during the interludes. It was only a pity they could not be seen, as the scenery was not raised during the time they sang' (The Bombay Standard, 13 December 1858, p 1146). By this time, the emphasis of military operations had passed progressively to the pursuit of increasingly demoralised groups.

Queen's regiments which had completed their overseas service were preparing to sail for home. The Standard carried reports of the trial of a notable accused of aiding the mutineers, of cantonment affrays between men of British regiments in Poona, and news of the wider world, but found space too for concerts by visiting artistes and recitals by regimental bands. A measure of normality was returning. In February Wooldridge placed what had come to be known as the German Choristers at the disposal of the Governor of Bombay 'to be called into requisition for the amusement of the lieges of Government House'. On 9 March, they appeared at the bandstand on the Esplanade, drawing one of the largest crowds ever witnessed in Bombay. Their singing was all that could be desired, said the Standard, 'but unfortunately a strong breeze was blowing, which prevented such an effect as would otherwise have been produced' (The Bombay Standard, 21 February 1859, p 348 and 10 March, p 469). Invisible in Poona, and partly inaudible in Bombay, the choristers were, nevertheless, winning plaudits. Having volunteered for active, potentially deadly, service, they were now performing on the Esplanade, and seemed destined to survive.

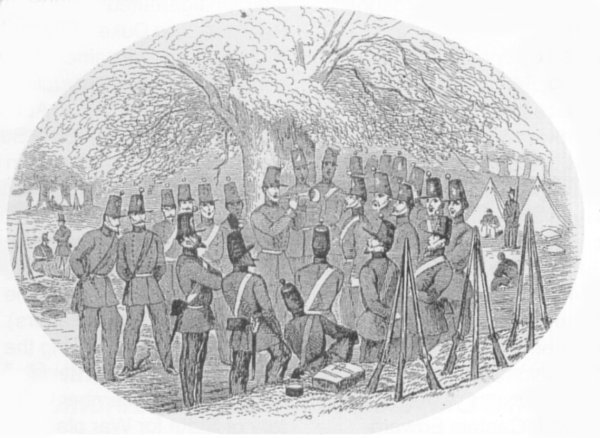

Members of the German Legion sing their national songs.

[Reproduced by kind permission of Michael George, author of Coast of Conflict].

On 5 March 1859, The King William's Town Gazette reported that letters and newspapers had arrived from friends in Poona. It printed an extract from The Poona Observer and passages from a letter lent by a Mr Peterson, both undated. Allowing for the voyage from Bombay to East London, the letters were probably posted in late January. The Poona Observer reported that Sir Hugh Rose, laden with laurels of the recent Central India campaign, had inspected the Corps, and complimented them as 'a fine body of young men'. Rose was in Poona only for a day, and the fact that he found time to visit them might seem unusual, but could be explained when we recall that he was born and educated in Berlin, where his father was Minister, and that he had received some military instruction at the Cadet School there. It may have been there that he had met the man who later, as King of Prussia, conferred upon him the Order of St John in 1842, expressing his pleasure on hearing that 'an early acquaintance' had so gallantly distinguished himself (Dictionary of National Biography, Vol XLIX, London, 1897, pp 233-40). The presence of a German regiment, some of whom were veterans of Continental wars, would have had a special resonance for him. The Gazette also carried a free translation of Mr Peterson's letter, which gave an enthusiastic account of life in Poona, its most pleasing feature apparently being that there were servants to carry out all nonmilitary duties. The officers had been welcomed by their British counterparts, and had repaid their hospitality. Pay was good, a captain receiving £50 a month, and the only complaint was that horses were expensive. The flank of the regiment was expected to go to Satara, some 100km south of Poona, and one of the ancient seats of Mahratta power - 'where we may earn a little glory'. As the letter was written in January, the reference to the movement to Satara ties in well with a report in The Poona Observer of 22 January that 400 men of the corps had recently been ordered for field service, although the order was later countermanded.

Understandably the European residents of Bombay, civil and military, seized eagerly upon any new intelligence. In mid-March, The Bombay Standard (19 March 1859, p 534) reported a rumour that 20 000 Germans were to be permanently stationed in India, two companies to every regiment. If this meant European regiments, and companies of a hundred men, it implied the permanent presence of one hundred Queen's or European regiments of the Indian Army; a tall order, though not perhaps as fanciful as it might seem. The Peel Commission, which submitted its report on 7 March, had recommended that 80 000 European troops would be required forthe defence of India, but could its recommendation have been known at the time that the Standard's story appeared? Could its source be a garbled version of Grey's letter to Elphinstone in September? The Standard was scathing, pronouncing jingoistically' ... if we cannot maintain India with our own strength we had better abandon it to anarchy and descend at once to the humble position which benefits [sic] a nation unable to protect its own'.

On 27 June 1859 a ceremonial parade was held in Poona in the presence of the Commander-in-Chief to mark the investiture of Sir Hugh Rose as Knight Grand Cross. Among the regiments required to provide troops was the Jager Corps, which contributed two companies with their band, confirming that the regiment, or part of it at least, was still in Poona (OIOC, L/MIL/17/4/429, p 120: General Orders, CinC, Poona, 25 June 1859). At the end of July, Wooldridge sought instructions from Somerset about two Germans who had made their own way from Egypt to join the regiment, adding that several others who had served under him in Turkey had offered to make their way from Hamburg if they were permitted to enlist on arrival. He reminded Somerset that 'the Regiment is reduced by cholera much below its establishment'. Clearly, he still hoped for a reprieve for his regiment, but the reply from the AdjutantGeneral's Department (OIOC, P/191/29, pp 68-9, Wooldridge to Somerset, 29 July 1859, and reply of Adjutant-General's Department, 14 September 1859) put paid to that:

'The Corps has been ordered to be broken up, and the men called upon to volunteer for the Bombay Artillery and Infantry, the officers being sent back to the Cape, no orders are necessary with respect to future enlistment in the Corps.'

Men continued to succumb to cholera and other diseases after they later elected to join the 3rd Bombay European Regiment, their German names and home towns in Germany in the casualty lists bringing to a melancholy end the long road and waste of seas they had travelled since they had enlisted in 1855.

Disbandment

Despite Somerset's prediction in December 1858 that the Jagers would soon be ready for action, they were not sent into the field and there may have been good reasons for that.a They arrived with a serious shortage of experienced company commanders. Newly arrived European troops needed a period of acclimatisation and, if thrown into the fray too soon, suffered severely from heat exhaustion and disease. This was now a war of rapid movement by small independent columns, consisting typically of British and Indian infantry, irregular cavalry and light artillery. Despite their sound grounding in Jager and light infantry manoeuvres, it may well have been the view that they might not adapt easily to operations of this kind in the hot season. Crucially too, their disbandment had been ordered. According to the Panmure Papers, Vol II, p 298n, however, '[the Germans] rendered material assistance to Great Britain in the Indian Mutiny', a reference, in all probability, to the deterrent effect that their presence had on disaffected elements in the large city of Poona and its neighbourhood.

On 12 September 1859 the Commander-in-Chief, Bombay, issued an order 'that the German Volunteer Battalion or "Jager Corps" is incorporated with the Army of this Presidency from the 5th instant.' (OIOC, L/MIL/17/4/514, p49, Headquarters, Poona, 12 September 1859). It was to be a choice between service in another regiment in India or a settler's life at the Cape and, when the terms of disbandment reached the Jager Corps, more chose to stay than to go. Thirteen officers elected to join the 3rd Bombay European Regiment, while seven returned to the Cape. The NCOs and men were divided in roughly similar proportions, the 3rd Bombay European Regiment receiving 560, the Artillery, 25, and 372 returning to the Cape (OIOC, L/MIL/17/4/429, p 203, Headquarters, Poona, 13 December 1859).

Benjamin declined both options and made his way back to Britain. In 1859, the 3rd Bombay European Regiment was transferred to Crown control, and later became the 109th Bombay Infantry in the British Army, the presence of so many Germans earning them the nickname 'the Jagers'. In April 1863, there were still four officers and 466 men in the 109th who had arrived at Bombay in the four ships from the Cape in late 1858, most of them bearing German names (OIOC, UMIU12/217, Nominal Roll of the 109th, 1 April 1863). The four officers were Captain (later Colonel) August Schmidt, Captain Edward Valentine, Lieutenant Wilhelm Luckhardt, and Ensign Oscar Schmidt.

The members of the Jager Corps do not appear in the Mutiny Medal Roll, presumably because they arrived in India too late to qualify, and the short-lived German Legion passed almost unnoticed into oblivion, leaving few traces other than weathered gravestones at Scutari, in the Eastern Cape, and in the cantonments of India. Of the thirty officers who went to India, Schnell says that only four - Herbing, von Bothmer, Loftier and Jacquet - returned to their original position as military settlers in Kaffraria. However, a list of grants of land in Kaffraria to men of the Legion contains the names of other officers who were disbanded in India, suggesting that they too may have returned to the Cape to claim their property (Schwar & Pape, 1958, pp 29-37).

After the Legion - Simner's later career

Despite the vicissitudes which he and his comrades had endured - the anti-climax when the BGL did not see action in the Crimea, the uncertainty and affrays before they were disbanded in England, the long voyage to the Cape, the disillusionment with a settler's life in Kaffraria, the adjustment to the climate, diseases and uneventful cantonment life in India, and finally another disbandment - Benjamin's taste for soldiering seemed undiminished. He left Bombay, probably in mid-November, passed through the Red Sea and crossed the isthmus to Alexandria. On 30 November, he sailed aboard the P&O steamer Ripon, and arrived at Southampton on 14 December (The Times, 10 December, p 7, and 15 December 1859, p 4). Within two weeks, he obtained a commission as an ensign in the Military Train, joining the 6th Battalion at Woolwich in February 1860 and accompanying them to Dublin in June 1861. He was promoted to lieutenant in November 1863 and, in December 1864, exchanged into the 53rd Foot. A year later, he exchanged again into the 76th Foot, later amalgamated with the 33rd to form the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellington's (West Riding) Regiment. He remained in the 76th for the rest of his service, becoming Instructor of Musketry and attaining the rank of captain in April 1875. He served with the regiment at Tunghoo in Burma and at Secunderabad and Madras in India, but was stationed at Chatham when he retired from the service in May 1877, a decision possibly hastened by the death of an infant son a few months earlier (Simner's army service is drawn from the PRO, W076/335, the Army List and his commissions, the originals of which are in the Simner Family Papers).

Not long after leaving the army, Simner seems to have regretted his decision to retire at the age of forty, and in September 1882 he wrote to the Secretary of State for War placing himself at his disposal 'for the service of my country anywhere' (Simner Family Papers). He enclosed with his letter a copy of another which he had sent to Lord Kimberley at the Colonial Office with a letter signed by eight Liberal MPs representing Welsh constituencies which recommended him for an appointment and referred to his father's 'valuable service to the Liberal cause in Wales' (Simner Family Papers). Through his father's London Welsh connections, he obtained employment in 1884 as Assistant Secretary in the London office of the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. After the Secretary died suddenly in 1891, he served for some months as Acting Secretary and, when in 1892 the College advertised the post of Registrar, he was one of six short-listed candidates, but was not appointed (University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, Council Minutes, 16 March 1892). Benjamin Simner died in London on 21 June 1903 and was buried in Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington. His brother Abel presented a stained glass window in his memory to the Welsh Girls' School, Ashford (now St David's School).

Notes

a. A few, at least, of the BGL eventually saw action. One of the regiments engaged in the war in Abyssinia in 1867-8, the 33rd Foot, contained 90 men who were said to be the remnant of the BGL 'raised for service in the Crimean War but had not been used and had ended up in South Africa instead. Now, for obscure reasons, they were made a part of HM's 33rd Foot in Abyssinia'. (B Farwell, Queen Victoria's Little Wars, Penguin 1973, reprinted by Wordsworth (Ware) 1999, p 170). Whether they came from the Cape, or from among the Jagers who had joined the 3rd Bombay European Regiment in India is not clear, but the 33rd were based in India when the expedition to Abyssinia was organised. (See also Darrel Bates, The Abyssinian Difficulty: The Emperor Theodorus and the Magdala Campaign, 1867-68, Oxford, 1979).

Bibliography

OIOC - British Library, Oriental & India Office Collections.

PRO - Public Records Office, Kew, now the National Archives (UK).

SFP - Simner Family Papers, now in the custody of Mrs Wendy Roderick and referred to with her consent.

University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, Council Minutes, 16 March 1892.

Dictionary of National Biography, Vol XLIX, (London, 1897).

Douglas, G & Ramsay, G D (ed), The Panmure Papers, Vol II, (London, 1908).

Schwar, J F & Pape, B E, Germans in Kaffraria, 1858-1958, (King William's Town, 1958).

The Bombay Standard, various dates.

The Times; 10 & 15 December 1858.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org