The South African

The South African

The Eighth Frontier War was played out in a wide array of theatres, from the dense jungles of the Fish River Bush, to the Amatola Mountains, along the line of garrisoned frontier forts, Fort Armstrong and Fort Cox amongst them, in the Alice - Keiskammahoek - Fort Beaufort triangle and northwards across the Kei. On one memorable occasion, Fort Beaufort actually came under all-out attack and was the scene of chaotic street fighting. Further north, the military villages of Auckland and Woburn were overrun while the hamlet of Whittlesea was subjected to a prolonged siege. The theatre of operations that has most captured the imagination of historians, however, is that of the Waterkloof, stronghold of the legendary Xhosa chieftain, Maqoma, and scene of some of the war's bitterest campaigning.

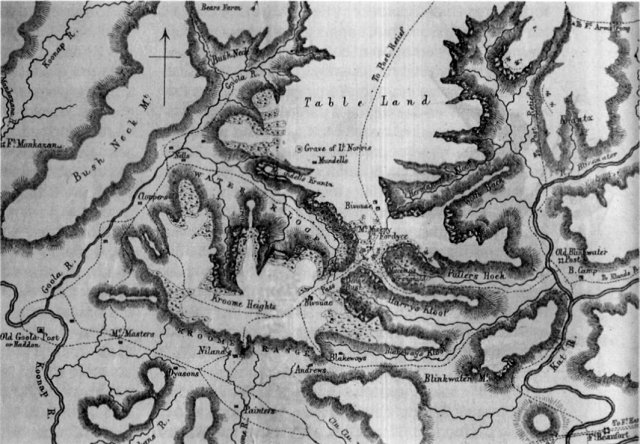

The Waterkloof, located roughly ten kilometres north-west of Fort Beaufort, forms part of a sprawling series of high hills and plateaus, intersected by deep, heavily-forested valleys, gorges and ravines. The Waterkloof itself is a deep, narrow valley, six kilometres long, bounded by the Kroomie Heights to the south and to the north by a second series of majestic ridges falling away to a rolling plateau. Running roughly south-east and open at its western extremity, it comes to a head in a high, grassy tableland fringed with bushes and gigantic trees. To the east, this tableland falls away into another deep, heavily-forested gorge, known as Fuller's Hoek. It was in this gorge, in a gigantic overhanging cave of a type that proliferates in the area, that Maqoma had his headquarters. The plateau is linked to the Kroomie by a narrow ridge and where this joins the plateau is a 'horseshoe-shaped flat', approximately a square kilometre in area and fringed by towering forests. References to 'the Horseshoe' (although the shape of the ground is far from obvious once you are actually there!) abound in the surviving first-hand accounts of the fighting that took place there. In due course it would be named 'Mount Misery' by the troops who fought in or near there.

The Waterkloof had not been the scene of any significant fighting in previous Frontier confrontations as between it and the main concentration of Xhosa power in the Amatolas to the east lay the Kat River Settlement. Here lived a large number of mixed-race settlers (referred to at the time as Hottentots and now generally, if not strictly accurately, called Khoi), loyal to the Cape Colony and comprising a high proportion of former soldiers who had served the Colony with distinction in earlier Frontier wars.

The Kat River Settlement, whose confiscation was a rankling bone of contention between the Xhosa and the Colony, had formed an effective buffer between the Amatolas and the Waterkloof-Kroomie heights and prevented serious Xhosa infiltrations there. By 1850, however, the situation had changed dramatically with the outbreak of the Kat River Rebellion. Hundreds of disaffected Khoi went over to the Xhosa side, capturing and briefly holding Fort Armstrong and making a fierce, if badly coordinated and ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to storm Fort Beaufort. The rebellion not only ensured that the anti-Colonial forces no longer had the Kat River barrier with which to contend, but also provided the Xhosa, and Maqoma in particular, with some of their most effective fighters. Certainly, the presence of sharpeyed, well-trained coloured marksmen helped offset the Xhosa's notoriously poor shooting skills. It also helped that the Khoi, having been in the Colony's service, knew all the bugle calls.

A serious threat

The seriousness of the Waterkloof threat was brought home to General Sir Harry Smith, Governor of the Cape, when a large patrol under Lieutenant-Colonel John Fordyce of the 74th (Highland Lightlnfantry) was forced to retire in some confusion following an ill-planned sortie against the Kroomie in September 1851. Early in the morning of 7 September, 613 men, mainly comprising the 74th, but also including detachments of Mfengu and Cape Mounted Rifles, ascended the Kroomie, marching through the dense forests before emerging on the rolling tableland on the summit. All was quiet at first, but later in the day the column began to be assailed by large number of Xhosa warriors sweeping down from the Fuller's Hoek area across the valley. Apparently led by Maqoma himself, riding a grey horse, these warriors swiftly began threatening to cut off the column's line of retreat. Fordyce was holding his own with ease, but it would have been suicidal to remain where he was as his men were already rapidly running out of ammunition. The column commenced its slow retreat, forced to walk in single file and pick their way with difficulty through the dense bushes and trees. Before long, they were being assailed from all sides by charging warriors and a desperate hand-to-hand fight ensued all along the line. The attack was eventually beaten off and most of the column eventually made their way to safety, having lost fifteen dead and about the same number wounded. The men had expended virtually all their ammunition by the time they made their way to safety.

For a young German bandmaster named Hartung, the horrors were just beginning. He had ended up joining the column through a misunderstanding and, during the retreat, was captured. The Xhosa, who had suffered heavy losses in repulsing the sortie, were not in a humane mood. One of their women subsequently recounted how the prisoner was systematically mutilated over two days before being finally shot. The Xhosa were destined to pay dearly for these and other wanton excesses once the Colony regained the upper hand, just as, three decades later, the Zulus would pay a disproportionate price when their uncompromising 'take no prisoners' policy saw the British respond in kind after the tables were inevitably turned.

Map of the Waterkloof

[Source: W D King, Campaigning in Kaffirland, London, 1853].

The campaign

The best known of the Waterkloof campaigns, on which Maqoma's military reputation largely (although certainly not exclusively) rests, took place shortly after the Kroomie debacle, from 12 October until 10 November 1851. Governor Harry Smith, recognizing that the war could not be won until the Waterkloof was decisively cleared, committed a considerable part of his available forces to that theatre. These included detachments of the 74th (Highland Light Infantry), 91st, 2nd Queens and 12th Regiments, Cape Mounted Rifles, Mfengu and some colonists. (Here it is worth noting that the Mfengu ['Fingo'] people, largely originating from Mfecane refugees entering the Eastern Cape from the north, as well as from marginalised groups within Xhosa society, were inveterate enemies of the Xhosa, serving the Colony with ruthless zeal during the later Frontier wars). This force was divided into two columns, commanded by Fordyce and the 91st's Colonel John Michel (Mostert, 1992, p 1117), all under the overall command of the veteran General Henry Somerset. There were four guns, later increased to six. (There is some confusion in the sources about Colonel Michel. John Milton, 1983, p 211, gives his regiment as the 2nd Queen's, while the editor of Thomas Baines' Journal of Residence in Africa, 1842-1853, 1964, P 227, claims it to have been the 6th.)

The son of former Cape Governor Lord Charles Somerset, Henry Somerset was by then a much-maligned figure in South Africa, certainly in the colonial press, which was bitterly critical of how the war was being conducted. Cape Governor Harry Smith privately railed against his incompetence, but strangely enough persisted in entrusting him with important assignments. This may well have ended up costing Smith his political career, since it was the failure of the second Waterkloof offensive that was decisive in his being dismissed and replaced as Cape Governor by Sir George Cathcart. It is fair to add that Somerset seems to have been popular amongst, if not perhaps particularly revered by, his men. Nor should his military abilities be too hastily dismissed. At one point in his memoir, Reminiscences of the Last Kaffir War, when describing a particular engagement, the 74th's Sergeant James McKay makes a point of stressing Somerset's coolness and decisiveness under pressure despite what his critics might say about him: 'Somerset - let people rail as they will - was equal to the emergency. His orders were calm and distinct. .. ' (McKay, 1970 reprint, p 147. McKay's Reminiscences incorporate one of the most compelling first-hand accounts of the campaign and has been heavily relied upon by such contemporary writers on the period as Noel Mostert, John Milton and Jeff Peires to recreate the events in which he was an active participant throughout. Captain W D King's Campaigning in Kaffirland, 1851-2, London, 1853, is another much-used source.)

The official war artist who accompanied the force was Thomas Baines, destined to achieve worldwide (if largely posthumous) fame but, at the time, considered to be no more than a competent journeyman artist. (He would no doubt have been astounded to know what prices the paintings and drawings he turned out with such dexterity would one day fetch.) It was fortunate for posterity that this highly gifted man was on hand to record the ensuing drama. In addition to the large number of oils, watercolours and sketches he completed - as haunting and vivid as any photographic record and aesthetically much more pleasing - the lively diary he kept provides an invaluable first-hand account of the campaign. Baines also participated, as the mood took him, in the actual fighting. Certainly, he frequently came under fire and on one occasion was nearly captured.

The second campaign

The month-long second Waterkloof campaign featured no set-piece battles, with clear-cut winners and losers. It was essentially an extended game of cat and mouse, made up of countless skirmishes, pursuits, ambushes, advances and retreats. As Noel Mostert put it, it became almost a war within a war, a self-contained struggle for mastery conducted in wild, isolated terrain, the awesome scenic beauty of which contrasted jarringly with the merciless nature ofthe actual fighting. Through gorges and ravines and dense, primeval forests, amidst thick bush and across rolling, grassy plateaus, Somerset's toiling columns pursued their elusive foes, sometimes inflicting considerable damage yet unable to inflict the knockout blow. Much of the fighting took place on and around the ridge linking the Waterkloof and Fuller's Hoek valleys, the aptly named 'Mount Misery'. For their part, the Xhosa and Khoi rebels alternated between attacking and retreating. Their greater mobility and intimate knowledge of the terrain was invaluable in enabling them to consistently take the British by surprise, although the generally poor marksmanship of the Xhosa, coupled with the inferior nature of their firearms, meant that the opportunities created to do real damage were seldom exploited.

Cairn in memory of Colonel Fordyce and the small wood

used as a temporary hospital by the British during the campaign.

This was located on the high ground on Mount Misery, commanding

the ridge between the Waterkloof and Fuller's Hoek gorges.

The physical demands made on Somerset's men were staggering. These included marching on occasion for eighteen hours at a stretch, usually on totally inadequate rations, and sleeping without tents in the open. Captain W D King of the 74th (1853, p 105) recounts how night marching in a state of semi-exhaustion led to hallucinating, something he found so unpleasant that he pinched his arms 'black and blue' in trying to shake it off. The persistent rain, and occasionally even sleet and hail, intensified the men's discomfort, and under the circumstances it is to be wondered at that only two soldiers are listed as having died from non-combat-related causes during the campaign. It is testimony to the men's stoicism that they managed to endure it at all, although this endurance was stretched to breaking point as the apparently fruitless treadmill of the campaign stretched on. McKay records two episodes of soldiers accidentally injuring themselves and then being accused of having done so deliberately. Both men were ultimately cleared of the accusations, but the fact that they had been accused in the first place is revealing. Given the hardships to which they were being subjected, it is not surprising that several men cracked under the pressure.

A private of the 74th, named Durbon, effectively committed suicide when, in apparent protest at being unreasonably marked down for special drill, he rushed into the bush where the enemy fire was thickest and was never seen again (McKay, 1970 reprint, p 149. By his own admission, McKay was not always completely accurate when recalling the various details of the campaign. There is no 'Durbon' listed as having been killed in the official records, possibly because his body was never found and therefore he remained officially 'missing'. It is possible that McKay was referring to the 74th's Frederick Duerdon, killed 23 October). Captain W D P Patten, also of the 74th, earned the scorn of his men by his cowardly behavior in action, something that did not, however, prevent him from trying to play the parade ground martinet once the danger had passed. The campaign abounded with haunting vignettes: the sound of Sunday hymn singing by the rebel Khoi wafting across the valley; a soldier risking his life to carry away the body of his slain brother; the mocking shouts of the Xhosa from the depths of the forests; perhaps above all the persistent stench of rotting corpses. The British were able to bury most of their dead - Maqoma's men did not enjoy that luxury. Nor were any of them to record, or systematically have recorded by others, their own no doubt equally harrowing experiences. Inevitably, our perspectives of the campaign are heavily one-sided.

It was a cruel war, with no quarter given on either side. McKay (1970 reprint, p 136) unsentimentally records, for example, how an old, wounded Xhosa warrior who attempted to save his life by feigning death was shot after his wound was discovered to be still bleeding. On another occasion, some Mfengu, rather than being bothered with guarding a captured Khoi, instead hung him from a tree and used him for assegai practice until he was dead. Sometimes, Xhosa women took part in the fighting. The 74th's Lance-Corporal McAlistair 'had two hollows, wherein might have been placed a good-sized hen-egg' made in his skull by knobkerries wielded by Maqoma's amazons. ('He lived', notes Sergeant McKay, 'but he was intellectually weak ever afterwards'). One Xhosa woman was caught trying to smuggle gunpowder to Maqoma. The Mfengu levies instructed to convey her to captivity in Fort Beaufort found it more convenient to tie a large stone around her neck and pitch her unceremoniously into the river.

Catastrophe

On 6 November occurred the catastrophe that was probably decisive in Somerset calling off the operation. That day began with the most concentrated British offensive yet, the plan being for four divisions to make a simultaneous attack from different directions and converge on Mount Misery. Somerset, with as many mounted troops as he could muster, was to ascend the Waterkloof while divisions of infantry and levies moved in from the Fuller's Hoek and Kroomie directions. Fordyce, with the 74th, 91st, two guns and Mfengu, was to advance from the north, across the plateau.

It was on Fordyce's division that the brunt of the day's fighting fell. This division was the first to arrive at Mount Misery, and was soon being fired upon from all directions from the bush and forests lining the flat. No.2 Company, 74th, which had been instructed to assault the section between the Kroomie and Waterkloof passes, instead began inclining too far to the right and, moving along a hollow, failed to observe the enemy in their front. With his men 'skirmishing in every direction around him ... charging and hurrahing', Fordyce shouted to the straying company to keep to the left, but his voice was drowned in the din of battle. He rushed down the small hillock on which he had been standing and, from an exposed position, waved his cap. It was then that a Khoi marksman shot him through the chest, the ball passing right through him. Within half an hour, he was dead. He is the most senior British officer to have lost his life in all nine Frontier Wars.

Baines, who was with Somerset's' division ascending the ridges of the Waterkloof, recounts how the men of the 74th could be seen extended along the cliffs on the north-west corner of the 'Horseshoe', keeping up 'an irregular fire towards the dark, surrounding forest, while three or four wounded men were being borne by their comrades to the rear' (Baines, 1964 reprint, p 245). These men, presumably, made up the wandering No 2 Company. They had succeeded in dislodging the enemy, but at a heavy cost, including another officer, Lieutenant Carey, and Sergeant Diamond shot dead and a number of other rank and file killed or wounded. The light company, 74th, coming up as reinforcements, also suffered severely - one man was killed and another mortally wounded by a single bullet fired at point-blank range - before the arrival of Somerset's men helped turn the tide. Two more guns were brought into the action and two companies of the 12th took over the position won at so h ig h a cost by the 74th. In addition to their popular Colonel, the 74th lost ten other men killed or mortally wounded, with a number of others seriously wounded. By Frontier War standards, these were heavy casualties, and certainly the loss of Fordyce was a crushing blow.

There was some more skirmishing on 7 November, but very little on the two succeeding days. On 10 November, the campaign was finally broken off and the various regiments were dispersed to other parts of the country.

British mass grave at Mount Misery. Most of the

British dead were buried at Post Retief.

The aftermath

There has been a tendency in recent decades to overstate somewhat Maqoma's achievement in withstanding the offensive of October/November 1851, the most concerted attempt yet to bring him to heel. This is obviously understandable in light of changing political realities and a justifiable desire to do justice at last to the Xhosa in their brave, doomed fight for freedom. It is also not baseless from a factual point of view. Maqoma was indeed still firmly entrenched in the Waterkloof when Somerset's jaded columns trooped wearily away for the last time, and the broader public, notwithstanding intimations by both Somerset and Smith that the campaign had achieved its objective, was well aware of the fact. The Eastern Province News, for one, stated bluntly that Maqoma had 'outgeneralled the first Division at every turn', remained 'proud master of the field' and must have had something 'approaching supreme contempt' for his opponents. This was certainly an exaggeration, characteristic of the often raucously critical tenor of the South African media regarding the conduct of the war and of the wretched Somerset's shortcomings in particular. It was also unfair to the battle-scarred troopers, who had stoically endured hardships and horrors that the carping critics in the comfort of their distant offices could hardly have dreamed about.

Maqoma indeed emerged on top in the second Waterkloof campaign, but, having said that, the extent of his victory must be put into perspective. In none of the innumerable skirmishes had the British suffered anything like a clear-cut setback; even the costly fight of 6 November saw them hold their ground and successfully storm their opponents' positions. Overall, their casualties were surprisingly low given the duration of the fighting, being well under a hundred out of the nearly 3 000 men engaged. The official fatality roll shows that only 27 of the regular troops were killed in action or died of wounds (nearly half of these casualties being accounted for in the 6 November fighting) and while King's and McKay's memoirs suggest that several names have been accidentally omitted, the real figure was certainly well under forty. The losses of the Mfengu levies were not, as usual, recorded, but judging from both Baines' and McKay's accounts, these also do not seem to have been especially high.

British Cemetery, Fort Fordyce. The men buried here

died of disease whilst manning the fort from July 1852.

The relatively low British casualty figure is a revealing indictment of Xhosa marksmanship, even taking into account the generally inferior nature of their weaponry, and which even the accomplished shooting of their Khoi allies failed to offset entirely. On the other hand, while bearing in mind the universal tendency of soldiers to grossly exaggerate the losses of their opponents, the number of Xhosa and Khoi killed during the campaignand this is in addition to the destruction of their homesteads and seizure of their cattle - was certainly not less than two hundred (and, quite possibly, double that figure). Following the first day's fighting alone, King counted eighteen enemy corpses on the particular path along which his regiment was marching, while the stench of rotting bodies concealed in the forests and bush testified to the presence of many more. The Xhosa and Khoi who hid themselves in the forests were generally well protected from musket-fire. Shellfire, on the other hand, accounted for many deaths, as the British patrolling the forests later discovered. By withstanding the invasion, Maqoma could justifiably claim a significant success, but the price paid was heavy and it paved the way for the Colony's increasingly one-sided victories in the three Waterkloof campaigns that followed, in March, July and September 1852.

It took only ten days for Harry Smith, now dismissed as Governor and fighting the last campaign of his extraordinary military career, to storm through the Waterkloof in March 1852. Maqoma's Den, the location of which had since been discovered, was captured and Maqoma himself was for a time forced to abandon his stronghold. Fewer than a dozen of the regular troops were killed in the operation. Maqoma reoccupied the Waterkloof shortly after the British withdrawal, but his power was largely broken. Cathcart's July offensive, during which a fort was built on the high ground of Mount Misery and named after the late Colonel Fordyce, easily dislodged him again. September 1852 saw the fifth and final Waterkloof campaign, and it was a massacre. Assisted by Lakeman's Volunteer Corps, described as 'a volunteer unit of psychopathic cut-throats' (weekend excursion notes, Denver Webb, curator of the Kaffrarian [now Amatole] Museum, October 1994), the British rampaged through the once formidable strongholds, slaughtering a weakened, demoralised foe almost at will and with virtual impunity. (The Roll of Honour of the 8th Frontier War, compiled by L Bagshawe-Smith and available in the Strange Library of African Studies, Johannesburg Public Library, shows that not a single fatality occurred amongst the regular troops during the final Waterkloof sweep.) Many non-combatants were also butchered, which more than cancelled out such atrocities as the cruel murder of Hartung, or of the sergeant of the 73rd who was crucified over a slow fire during the March 1852 offensive. (The unfortunate sergeant was found alive but died shortly after being rescued). It was the end of Maqoma's long and gallant stand in the Waterkloof. For all practical purposes, it was also the end of the war itself, although, officially, this dragged on well into 1853 before the final surrender of Maqoma, his half-brother Sandile, and the other Xhosa chiefs.

The Waterkloof Today

Regrettably, many important Eastern Cape military sites have been abandoned to Nature's remorseless attrition. For example, Fort Cox, where Harry Smith was famously cooped up during the early days of the 1850-3 War, has been reduced to a bare outline of stones, the site almost completely covered by low thorn trees and its small military cemetery so derelict as to be almost indistinguishable from its bush-choked surroundings.

Fortunately, the Waterkloof today comprises part of the Fort Fordyce Nature Reserve, which bodes well for its future as a national heritage site. It has become a popular destination for hikers and rock climbers, but, from an historical conservation point of view, a great deal still needs to be done. A small military cemetery, where a handful of men who died whilst manning Fort Fordyce are buried, is in serious need of renovation. Even more pressing is the need to properly demarcate a cluster of unidentified graves located in a glade next to a small dam not far from the site of the old fort. Unlike the first group of graves, these are almost certainly the final resting places of soldiers killed in the actual fighting, and since most British fatalities were buried, or reburied, elsewhere, notably at Post Retief or near Mundell's Farm on the plain further north, and are therefore already identified, careful research might well determine who these unknown fighters were. Nothing remains of the old fort, but its outline can still be seen clearly and an appropriate memorial plaque for the site is certainly required. Nearby is a rough stone cairn, reputedly located on the spot where the mortally wounded Fordyce finally expired and erected in his memory (this may need to be verified). Also in the immediate vicinity are the 'hospital trees', the same impressive cluster of towering evergreens that acted as a temporary hospital for the wounded during the campaign. The enormous overhang forming the cavern immortalised as 'Maqoma's Den' is more than a kilometre away in the Fuller's Hoek gorge. A great deal of careful field research is still needed to identify other important features where the incidents described above took place, particular in and around the area of the famed 'Horseshoe' flat. This would include identifying, with a reasonable amount of certainty, the approximate area where the 74th Regiment suffered so heavily on the fateful day of 6 November 1851.

Overnight accommodation for visitors is available at Maqoma's Den or Loerie's Rest, two unpretentious but comfortable and reasonably priced guesthouses located within sight of the old fort. One can also camp there with prior arrangement with the manager, Thinus Pienaar (Tel: 046-684 0729 or 082 730 2799). The turn-off to Fort Fordyce is 10km outside Fort Beaufort and continues for a further 14km up the mountain. The thrilling drive and spectacular view from the summit, encompassing the Hogsback, Katberg and entire Kat River Valley, alone make a visit worthwhile.

Further reading

Bagshawe-Smith, L, 'Roll of Honour of the 8th Frontier War', Strange Library of African Studies, Johannesburg Public Library.

Baines, Thomas, Journal of Residence in Africa, 1842-1853, (Van Riebeeck Society reprint, 1964).

King, Captain W D, Campaigning in Kaffirland, 1851-2, (London, 1853).

McKay, James, Reminiscences of the Last Kaffir War, (Struik reprint, 1970).

Milton, John, The Edges of War, (Cape Town, 1983).

Mostert, Noel, Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa's Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People, (Pimlico, 1992).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org