The South African

The South African

It [h]as long been assumed that the cattle horns in the Natal Museum were the work of a Zulu artist attached in some way to the Imperial Forces. In his article, 'A glimpse of colonial life through Zulu eyes: Nineteenth century engraved cattle horns from Natal', (Natal Museum J. Humanities, Vol 2, pp 143-62, November 1990), Dr Tim Maggs states that the horns in question 'include some of the earliest known narrative representation work by Zulu artists who thus give us a glimpse of the alien and dominant colonial way of life.' The writer believes that this is a myth and that, in fact, the horns numbered 176 and 176a (as catalogued by the Natal Museum) were not engraved by a Zulu but rather by a member of the Naval Brigade who was besieged in Eshowe between 24 January and 3 April 1879. The rationale behind this statement is as follows:

Firstly, the type of art form used is known as scrimshaw work. This was popular amongst seafarers of the nineteenth century and, while it was usually done on walrus tusks or narwhal teeth, there would hardly have been a supply of these materials at Eshowe. It was recorded that, during the siege of Eshowe, the daily beef ration was 1.5 lbs per man per day and, with some 1 300 troops besieged there, this would have meant that two or three cattle were slaughtered every day. Thus, there would have been no shortage of horns! (British Intelligence Narrative, p 57, 13 March 1879).

Single horn, No 177, Natal Museum, Pietermaritzburg.

Details from the single horn, No 177, showing motifs of buildings and

fish which strongly suggest tha the artist was a European.

Secondly, there is no record of any earlier Zulu art depicting the human form in the detail as engraved on the horns. The writer was unable to trace any such work until the figures carved in wood by Ntizenyango Qwabi kaQomentaba at the beginning of the twentieth century (Killie Campbell Library and the author's private collection). This lack of any similar or earlier Zulu art is pointed out by Dr Maggs in his article. On the other hand, scenes of whaling and shipboard activity showing human figures are a common feature of scrimshaw work.

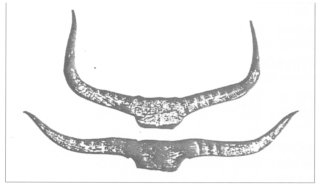

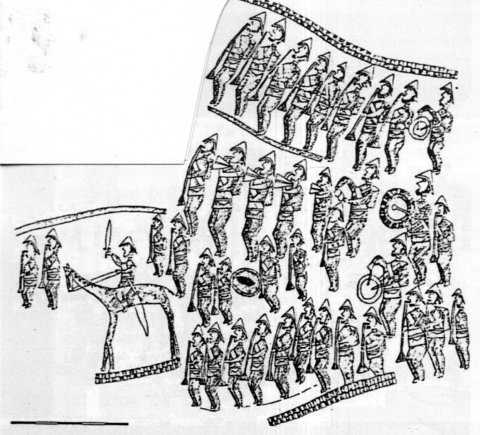

By a different artist? The paired horns, Nos 176 and 176a, at the Natal Museum, Pieterrnaritzburg.

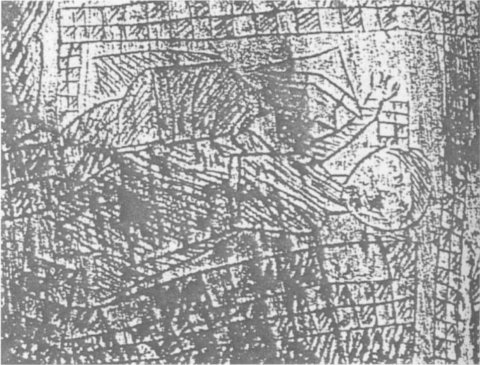

Thirdly, there are several factors inherent in the carvings themselves which support the theory that the horns were the work of a sailor or Marine from the Naval Brigade rather than of a Zulu. The single horn (No 177) appears to have been made by a different artist to the paired horns (Nos 176 and 176a) which are still attached to the skull of the ox, the facial bones having been removed. In the case of the single horn (No 177), very distinctive European characteristics are evident. The writer does not believe that this horn was engraved by a member of the besieged garrison in Eshowe. It is more likely to be the work of someone from a garrison force at Pietermaritzburg or some other large town. The scenes depicted on the horn are mainly of buildings. The fish shown on the horn are very reminiscent of the scrimshaw work of sailors and show a close association with matters aquatic in the mind of the carver. As the Zulu people of that era did not eat fish and saw them as close relatives of snakes, it is unlikely that a Zulu carver would have depicted this subject. This horn is not nearly as interesting or as informative as the others and the writer has not spent time researching its origins.

The two pairs of horns, Nos 176 and 176a, are far more interesting. With the aid of a magnifying glass, one can see, in the case of No 176, that the facial bones were removed using a small toothed saw. Although this type of tool would have been available to Imperial forces, it is unlikely that a Zulu would have been in possession of one at that time. (No carpenter likes to lend out his saw - try asking one!) It is not possible to see just how the facial bones were removed from No 176a as the end of the boss where it was cut is covered in plaster of paris.

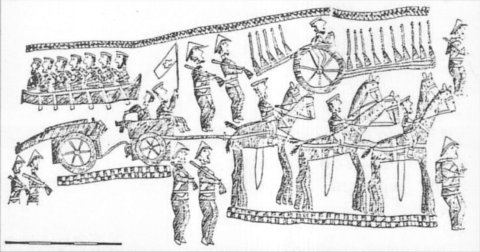

Horn 176a

This could depict the Naval Brigade rowing across the Thukela River on 6 January 1879, when they pulled the cable across the river for the first time. It was washed away in a flood two days later, but the anchor was recovered and the steel hawser re-laid successfully by members of the Naval Brigade on 10 January. With the aid of spans of oxen, this cable was subsequently used to pull the pontoon across the river until such time as a pontoon bridge was built.

The etching of this subject is interesting in that it shows the coxswain in the boat facing the stern, which he would have been doing if the rowers had been pulling a cable across the river. The rowers are shown correctly with their backs to the bow of the boat in true Naval fashion. In contrast, the Zulus used dug-outs, faced forward, and paddled rather than rowed. This is a detail with which someone with a Naval background would certainly have been familiar, but a Zulu craftsman not necessarily so.

A fully-laden pontoon prepares to cross the Thukela River,

January 1879. (Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

The checker board lines

The horizontal lines dividing the engraved figures on the horns are of the same checker board pattern and design as that used immediately below the bulwarks of some 'ships of the Line' in the early 1800s. Whilst this design could be a Zulu motif, it is most certainly a Naval one.

Gun carriage and limber

The detail with which these have been depicted shows a very close knowledge of the unit. Any Zulu recording these weapons in such detail would probably have been shot as a spy!

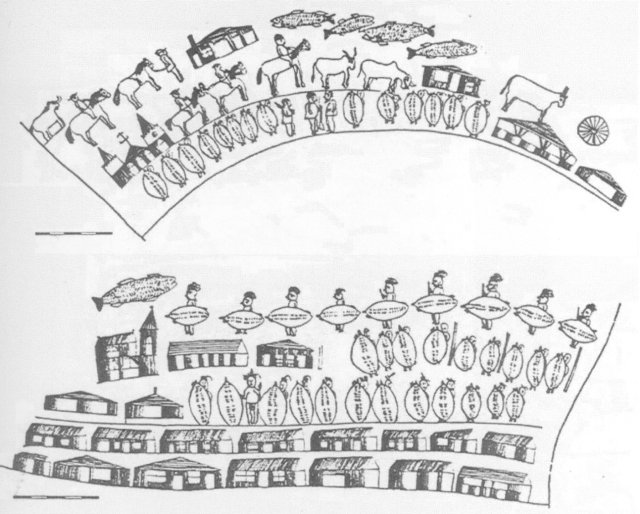

Horn No 176a, left side

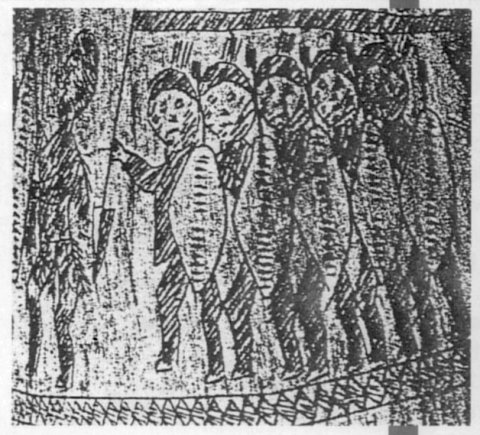

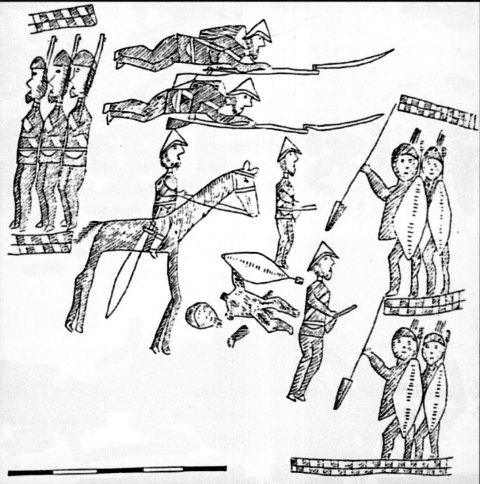

Zulu warriors and marching soldiers

This section showing Zulu warriors holding their shields in formation is problematic. If the horns were the work of a Zulu artist who was sufficiently observant to correctly portray many of the details of the Imperial forces, it seems unlikely that he would have made such a glaring error in the Zulu shields, depicted as having only a single line of lacing. Surely a Zulu would not make such a mistake? It would have been impossible to hold the shields as shown with just a single line of lacing. This error is evident in all the engravings which show Zulu warriors.

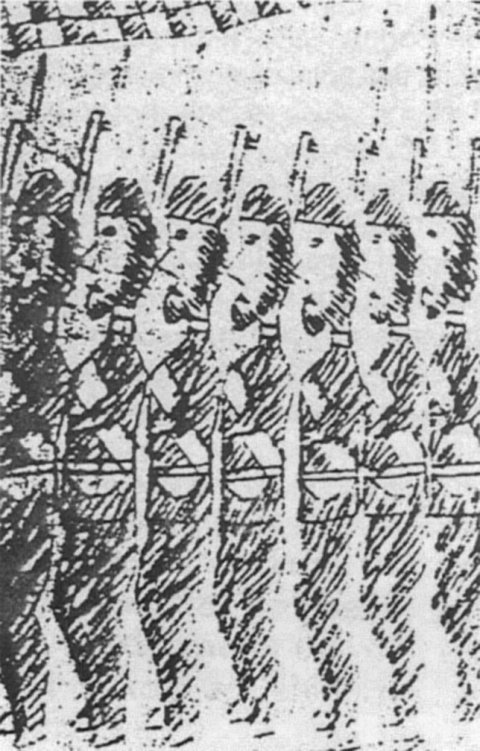

Two armies on the march. Zulu warriors (above)

and British soldiers (below).

In contrast, the second image shows soldiers on the march. The detail of the uniforms and equipment of the Imperial forces are far more accurately depicted than those of the Zulu forces, another indication that the engraver was probably a European.

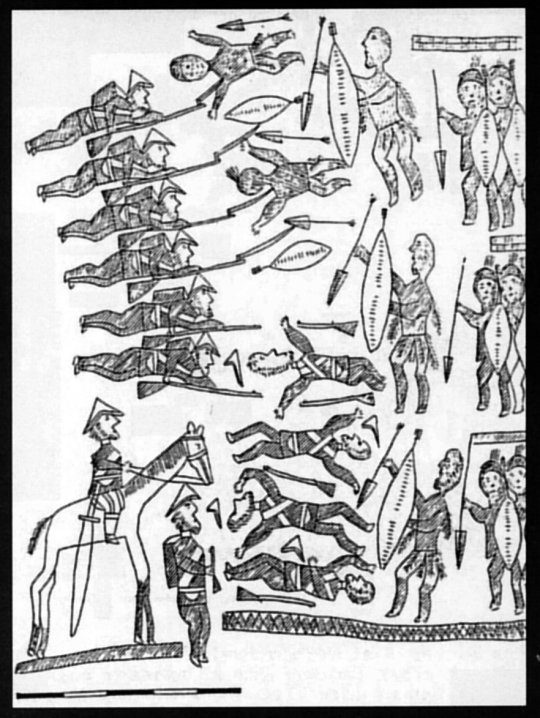

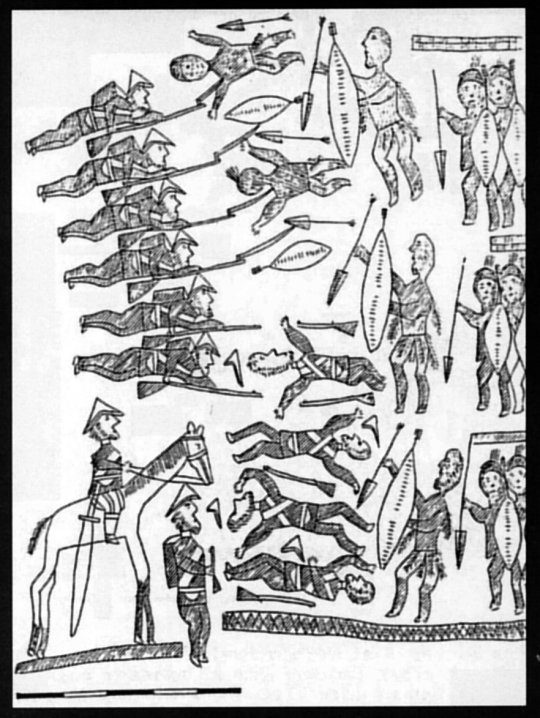

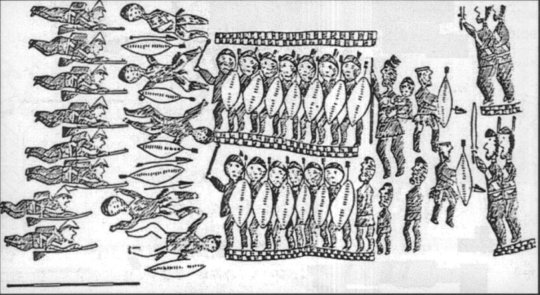

BATTLE SCENES

A battle scene

The first action in which a member of the Naval Brigade would have taken part was the Battle of Inyezane on 22 January 1879. This could well be what is depicted in these 3 images:

(Dr Tim Maggs comments on the unusual tufts at the ends of the Zulu spears, a mistake that could well have been made by someone seeing Zulu warriors in their battledress with their cow tails and feathers waving, but not by the Zulus themselves).

The next two images show dismembered Zulu dead, which Dr Maggs suggests may have been caused by shell fire. The Naval guns were brought into action at Inyezane and caused recorded casualties amongst the Zulu.

Could these two battle scenes possibly be depicting

the Battle of Inyezane, 22 January 1879, the author asks?

This battle scene, like that at the top left, shows a dismembered Zulu warrior.

Are these the results of the devastating power of British Naval guns

brought into action at the Battle of Inyezane?

A battle scene

The image below is interesting in that it depicts Zulu women and children involved in a battle. This might represent the occasion when a force from the garrison of Eshowe attacked two neighbouring kraals, Esqkayne and Enhlanguibo, during a sortie on 1 March (War Office Papers, 33/34, p 365, 1 March 1879). Details of this action are sketchy, but the kraals were surrounded by a force of four companies of the 3rd Regiment (The Buffs), one company of the 99th Regiment, thirty mounted men and twenty Marines. Although most escaped before the kraals were surrounded (British Intelligence Narrative, p56), it is possible that some women and children were caught in the kraal.

The illustration seen here is interesting in that it depicts

Zulu women and children at the rear of the Zulu lines.

Everyday life during a three-month siege

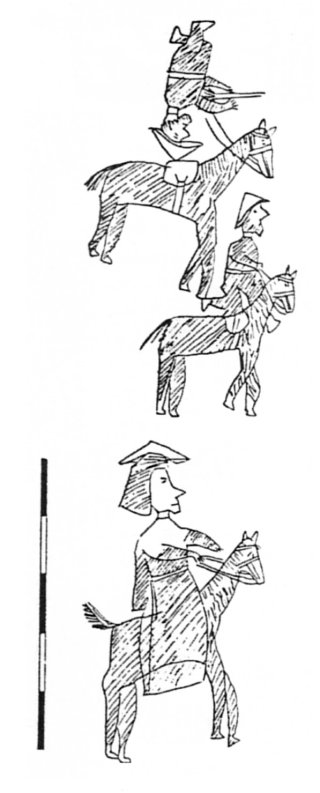

Stunt riders and a lady in a side-saddle

To beat the boredom of the siege, members of the garrison seem here to be showing off their riding skills. Although most of the horses left Eshowe on 29 January with Major Barrow and his men (British Intelligence Narrative, p 54, 29 January 1879), a number of officers' horses and sick horses remained behind. It is estimated that at least thirty such horses would have been left behind, given that this is the number of mounted men recorded as having taken part in the sortie of 1 March described on p 139. Before the march on Eshowe, it is recorded that 'both the 99th and the Buffs vied with the 13th and 90th in their equestrian proclivities .. .' (Ashe & Wyatt-Edgell, p 178). The woman riding in a side-saddle might have some connection to the Embrace described here (right). Here, the workmanship would appear to be attributable to a seaman - only a sailor would have the woman sitting on the wrong side of the horse!

The Embrace

This image depicts a British soldier apparently embracing a woman figure. It seems unlikely that a Zulu craftsman would have dared to use such a delicate subject using Europeans as the central characters, again supporting the notion that the artist was a European.

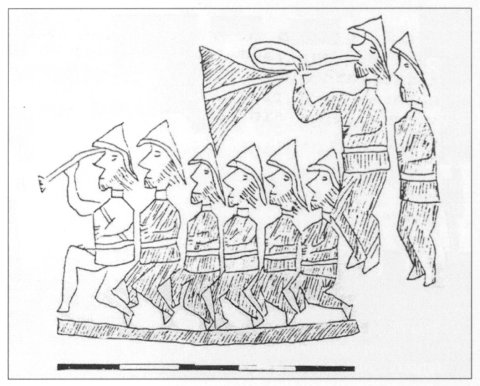

The Marching band

Below is a representation of a marching band. Two bands were besieged in Eshowe, those of the 3rd Regiment (The Buffs) and the 99th Regiment of Foot. Both bands are reported to have played daily (British Intelligance Narrative, p 56, 20 February 1879), no doubt providing an entertainment highlight during the three-month siege and thus worth recording.

Dancing soldiers

Led by an officer carrying a telescope, dancing soldiers are depicted in the illustration below. The daily entertainment provided by the two bands would almost certainly have featured tunes from Gilbert and Sullivan's popular operetta, 'HMS Pinafore', first performed on 28 May 1878. It would therefore seem that the dancing soldiers are performing the song, 'I am the Captain of the Pinafore, and a jolly good Captain too!' During the siege of Eshowe, 'lawn tennis, bowls, nine pins and quoits were devised. Concerts were organised and dramatic recitals on a modest scale were improvised .. .' (Ashe & Wyatt-Edgell, p 178).

Marching soldiers

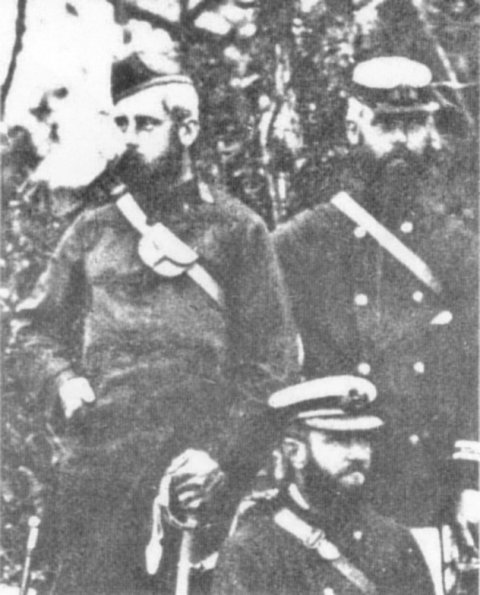

Donning a glengarry cap while on service with the Naval Brigade

during the Anglo-Zulu War is a member of the Royal Marines (above, left).

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH, Johannesburg).

The soldiers seen below are identified by Dr Maggs as members of a Scottish regiment owing to the fact that they appear to be wearing Glengarry caps. There were no members of Scottish regiments at Eshowe, but members of the Royal Marines from the Naval Brigade, who were at Eshowe, did wear this form of headdress. The photograph above, detail from a larger Naval Brigade group photograph, shows a member of the Royal Marines wearing a Glengarry cap.

The angel

The angel depicted here has always led to the assumption that the Zulu artist was a Christian. There is another, more plausible, explanation for her presence, however. While besieged in Eshowe, the Naval Brigade attended regular church services on a daily basis (Emery, p 212). Staff-Sergeant Beatson, of the 99th Regiment, by all accounts a deeply religious man, recorded the church services that were held. A Wesleyan Methodist, he recorded that church services were held in conjunction with Bible classes. 'Sometimes, when our meetings were crowded' he wrote, 'the blue-jackets would go aloft, where they seemed more at home.' It seems logical that it would not take long before the foot soldiers on terra firma began referring to the blue-jackets, aloft, as angels.

Bibliography

Ashe, Major & Wyatt-Edgell, Capt E V, The Zulu Campaign, (1880).

Barthorp, Michael, The Zulu War: A pictorial history, (Poole, 1980).

Bourquin,S, and Johnston, Tania M, The Zulu War of 1879.

Clammer, David, The Zulu War, (St Martin's Press, 1973).

Clarke, Sonia Zululand at War, 1879: The conduct of the Anglo-Zulu War.

Emery, Frank, The Red Soldier, (Hodder & Stroughton, 1977).

Forsyth, D R, The Medal Roll: South African War Medal 1877-8-9, (Privately published, 1978)

.

Gon, Philip, The road to Isandlwana: The years of an imperial battalion, (Ad. Donker, 1979).

Intelligence Branch of the War Office: Narratives of the Field Operations connected with the Zulu War of 1879.

Maggs, Dr Tim, 'A glimpse of colonial life through Zulu eyes: 19th century engraved cattle horns

from Natal' in Natal Museum J Humanities, Vo12, November 1999, pp 143-62.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org