The South African

The South African

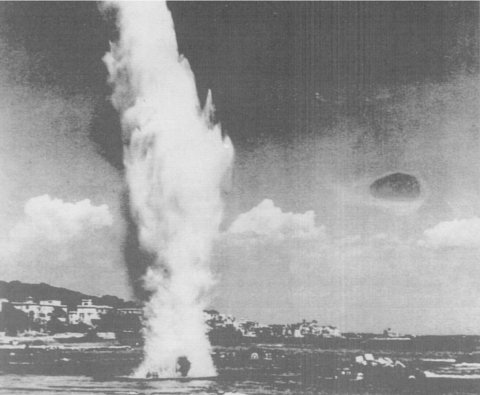

A shell from Anzio Annie explodes on the beach.

(Source: Purnell, History of the Second World War, 1973).

Ask any Second World War veteran the name of a famous gun and almost certainly he will answer: 'Anzio Annie!' The age-old military doctrine that 'the longest arm has the hardest punch' gave rise to a family of guns with extreme range as their dominant feature. It also gave rise to some famous names, such as 'Long Tom,' 'Atomic Annie', 'Heavy Gustav', 'Long Max' and, possibly the most famous of them all, 'AnzioAnnie'.

Long range required mass and size and, with their heavy load and rapid movement capabilities, railroads offered, in the railway gun, a viable alternative to the limitations imposed by road transportation. Rail transport had geographic limitations, but it offered a unique feature - tunnels. As we shall see, Anzio Annie made good use of this feature.

Development of the railway gun

Most armies have tried their hand at designing a railway gun, but none more so than France and Germany. The reason for this is clear - the extensive rail network of Europe favoured its military use. However, the inherent inaccuracy associated with long range dictated that the role of the railway gun would be to disrupt rear assembly points of troops and supplies. Not all armies thought this way and, after the First World War (1914-18), with the increasing dominance of air power, many railroad guns were relegated to the bone-yard of obsolescence.

With the cessation of German arms production after the First World War, that country's remaining guns and machinery went to the melting pot. Instead of stifling arms design, however, this created opportunities for innovators to design new weapons 'without the constraints of existing machinery or stock lists. Victorious armies did not have this advantage; existing guns could not just be discarded, since they had been paid for and were on the stock list. In 1920, therefore, when limited arms production was resumed in Germany, new designs for long-range guns were already on the table.

The new family of guns was classified according to their design range. Thus, the K12 E (where 'K' stood for 'Kanone' [gun] and 'E' for 'Eisenbahn' [railway]) was designed to fire 120 km, whereas K5 was to reach 50km. Calibres ranged from 280mm to 800mm. Many designs used barrels intended for the Navy, to obviate unnecessary duplication and, sometimes, as a ruse to conceal their real purpose. Primarily intended for rear area interdiction, the massive fortifications of the Maginot Line constructed by France were considered possible targets in case of war. In addition, the new guns afforded a laboratory for the testing of rocket-assisted and other special purpose projectiles, such as the Peenemunde arrow shell. The optimum range gun of this series, the K12, was used to shell Kent at a range of 160 km, firing from the French coast near Calais. This gun was not particularly successful and only two were completed.

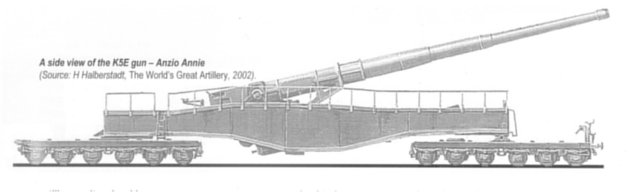

Without question, the most successful gun of the series was the K5E, of which a total of 21 were built during the late thirties. The well-known artillery writer, Ian Hogg, describes the K5E as 'probably the most successful railway gun ever built'.

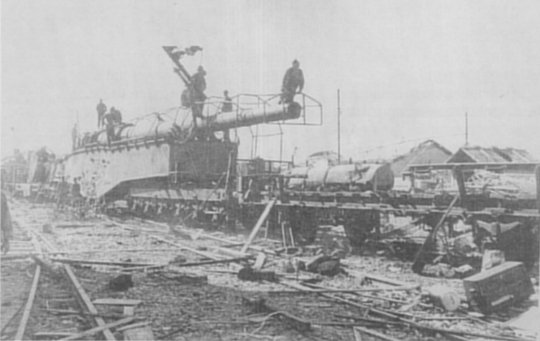

A side view of the K5E gun - Anzio Annie

(Source: H Halberstadt, The World's Great Artillery, 2002).

Anzio Annie

But who was Anzio Annie and what made her so famous? Anzio Annie was just one of the 21 K5 E guns built in Germany by Krupp Steel, the traditional supplier of heavy guns to Germany. Through the years, Krupp acquired a reputation for building famous guns, such as Big Bertha, Heavy Gustav, and the Paris Gun.

Anzio Annie's vital statistics were quite impressive:-

| Calibre: | 280mm |

| Barrel length: | 21.5m |

| Overall length: | 41.2m |

| Mass in action: | 218 tons |

| Mass of HE shell: | 260kg |

| Muzzle velocity: | 1 128m/s (Mach 3.3) |

| Maximum range: | 63km with HE shell, 151km with the special Peenemunde arrow shell |

| Breech: | Horizontal sliding block |

| Rate of fire: | 15 rounds per hour |

| Traverse: | 2° |

Her 218 ton mass was spread by means of a huge rectangular box girder holding the gun trunnions and supported over two railcars, with twelve axles in total, giving exceptionally clean and slender lines to this gun.

The best contemporary British railway gun at Dover, the 343mm 'Gladiator', could fire a 570kg HE shell to a maximum range of 37km. For this bigger shell, of course, range had to be sacrificed. The South African National Museum of Military History's own 155mm G5 gun can fire a 45kg shell to a maximum range of 39km. But the G5 is a road gun and South Africa's only contribution to railway guns was the 152mm naval guns used by the British during the Boer War, which could reach 14km. This could outrange the Boer Long Toms, but then these guns were rail-bound, whereas the Long Tom could go anywhere - and did!

The German gunners, quick to invent an fitting name, called the series the' Schlanke Bertha' ('Slender Berthas'), which was most appropriate owing to their lean profile.

The first shots fired in anger by these guns were the 36 shells fired from Calais at the English coast - some at the Dover radio towers - at the beginning of the Second World War. This was more for experimental and range purposes than to take out specific targets. Thereafter, the guns were held in readiness in Europe.

Anzio Annie into action

The real Anzio Annie saga started in January 1944, when the Allies landed at the Italian port of Anzio in order to short circuit the deadlock at Cassino, where German resistance had stopped the march to Rome. Under US General Mark Clark, with General John Lucas as local commander, 35 000 troops landed at Anzio beach, increasing to 50 000 by Day Four. It was an easy landing, with negligible losses and minor opposition. Mark Clark was a West Pointer and a First World War infantry veteran. During the Second World War, he showed great skill in handling troops of mixed nationalities, was energetic, ambitious and strong-willed, but even he found Anzio a tough nut to crack. Opposing him were 10 000 quite unprepared Germans under General Albert Kesselring, with General Eberhard von Mackensen as local commander, who quickly reinforced his troop numbers to 60 000 men. Between the wars, Kesselring, a First World War artillery veteran, transferred to the Luftwaffe, and showed himself to be a resolute and skilful defensive commander, nearly defeating the Allied effort in Italy, and bringing the invasion to a standstill at Cassino, which precipitated the Anzio landing.

With two Grand Masters at the chessboard, the deadly game was ready to begin. From then on, every move was followed by a carefully considered countermove, with each player striving for the masterstroke that would give him a decisive advantage. One of the first moves made by Kesselring was to send two railway guns to Anzio. An opportunity was missed when the Allies fired on, but failed to intercept, a train of railway guns moving through the morning haze on the Naples-Rome line. It was to cost them dearly. British intelligence actually predicted no more than light gun emplacements with maximum size of 88mm to oppose the landings, and railway guns were not considered. Due to excellent German security, Allied intelligence remained largely ignorant of the existence of these railway guns.

The first German guns to shell the landings were those from a captured 280mm French battery now commanded by Captain Borcherds, who used 'shoot and scoot' tactics to escape the usual aerial retaliation that followed a bombardment.

The strategy

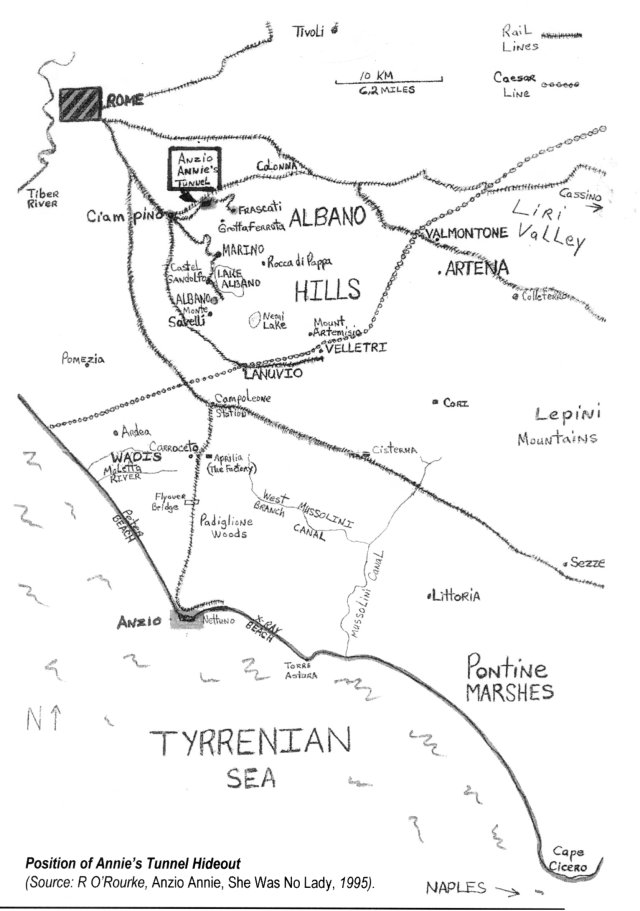

By then, two K5E batteries (ie two guns), named Leopold and Robert, had arrived from Rome and the game began in earnest. Col Frederik Filzinger was put in command of the railway guns, and he worked out a strategy to bombard the Allies to the point of withdrawal. Railway guns have the disadvantage that camouflage and concealment are difficult, but, at Anzio, the solution presented itself in the form of a tunnel at the right place and the right range. Not even the most ingenious of experts could have invented a better hideout for a railway gun than in a tunnel. From there, it could run out and open fire and, as the inevitable aerial and artillery retaliation followed, run back to its retreat. Safe from observation and bombardment, it was the ideal hideaway.

Col Frederik Filzinger, Annie Commander

(Source: R O'Rourke, Anzio Annie, She Was No Lady, 1995).

The tunnel that Filzinger decided on was on the Ciampino-Frascati branch line, approximately 12km from Rome, and 30km from the Anzio beachhead. It was an ideal position for long-range interdiction, well within Annie's range, but outside the range of Allied artillery. The US 155mm Long Tom, the top of the Allied range, could only reach 23km, still 7km short of touching Annie. Filzinger appointed Capt Borcherds, a First World War artillery veteran, as the on-site commander of the two teams of K5 batteries,with Sergeant Sauerbier as one of the bombardiers. (Borcherds died in 1984, aged 93.)

The technicalities

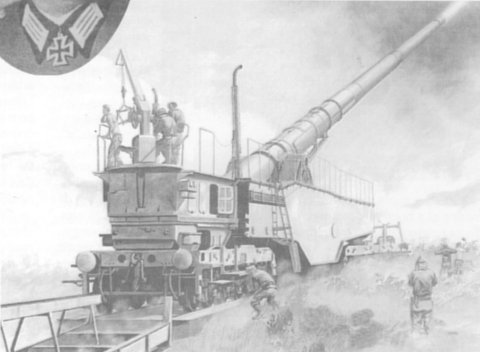

A gun train consisted of six special railcars, one for the crew, a kitchen car, an air-conditioned munitions car for keeping the powder at a constant temperature of 10°C, a maintenance car, an anti-aircraft gun car, and, of course, the gun itself, all powered by a diesel locomotive. Two such trains were used, with the less important cars, like the kitchen and maintenance car, placed near the tunnel entrance to minimize damage in case of a raid.

Diglycol was used as powder, three bags of powder per round, and this and the shell were pushed out on a cart and lifted by crane to the gun platform. A special loading pole with grooves was used to ensure correct engagement of the twelve splines on the shell into the barrel rifling. The last bag of powder was enclosed in a brass case to ensure obturation. As much as possible of this was done in the tunnel. Usually only one gun fired, the other staying in the tunnel, but at times both guns were in action. For air defence, each gun train had two 4-barrel 20mm AA guns and one 88mm AA gun.

Anzio Annie in action. A soldier can be seen yanking the lanyard.

(Source: Joachim Engelmann, German Railroad Guns in Action, 1976).

The next step was to create systems of deception in order to render detection of the guns, from the air or otherwise, as difficult as possible. To this end, Filzinger had a number of dummy guns built in wood and iron, painted like the real thing, and covered with camouflage netting. The dummies were dispersed at railway yards in the vicinity. To confuse the spotting of muzzle blast, flash simulators were erected at various sites as well as at the dummy gun sites. These simulators were fired to coincide with Annie's shots. As we shall see, these efforts proved to be highly successful. This addressed the basic problem faced by any artillery battery operating in the open. Once the smoke, sound, or flash of a gun is spotted, a retaliatory bombardment will surely follow. To escape this, the battery would have to move to a new position, requiring setting up and range-taking all over again. Annie's hideout obviated all this.

When the gun was ready, with the target position worked out beforehand, it was pushed out of the tunnel by a diesel locomotive into the rail yard, quickly sighted, and fired. Traverse was achieved by using curved rail tracks, apart from the inherent 2° traverse. Reloading was done at the double. At night, the muzzle flash was 30 to 40 metres long, and could be seen for many miles. To reduce detection, Deuneberger salts were added to the charge to reduce muzzle flash to just a thin, pencil-like, flame.

First shot was a special ranging shell, raising a massive black smoke plume to make it easily visible. An observation post would radio the fall of shot and corrections were made on this. Eventually, only 45 seconds were needed to report the fall of each shell to the gunners. After firing six to eight rounds, requiring some four to seven minutes per round, the gun was pushed back into the safety of the tunnel. Important maintenance work could then be done.

Annie's effects

Soon the heavy and bitter taste of the German genius and artillery expert - Krupp Steel - would be felt. With the beachhead only 30km away, it was the classic irresistible force meeting an immovable object, as both sides strove for the advantage. Suddenly the Allies realised, the hard way, that the railway gun was far from being obsolete.

Annie's targets presented themselves as ammunition dumps, gasoline dumps, ships in harbour, troop concentrations, supply dumps, and harbour installations. The landing force did not have the immediate opportunity to disperse these; being on a beach, space was limited and there was no place to hide. Thus, Annie could virtually pick and choose her targets. A prime objective was to force supply ships to anchor further away from the beachhead, thus obstructing and delaying the delivery of supplies, since barges and ferries had to be used, creating even more targets. Observation posts kept Annie continuously informed of possible targets.

The bombardment

On 5 February 1944, thirteen days after the landing, the gun known as Robert opened fire first, landing fifteen rounds on the beachhead. The effect was stunning, since no artillery fire of such magnitude had been expected from that direction. The Allies actually thought there was only one K5 gun, and quickly dubbed it 'Anzio Annie'. It would also become known as 'Whistling Willie' or 'Anzio Express', the latter name no doubt due to the shell sounding like an express train as it roared overhead. The immediate reaction of the those on the beachhead was to locate the position of the gun in order to take it out.

On 16 February, Robert and Leopold fired fifty rounds and repeated requests to silence the guns were followed by fighter-bomber attacks with 500kg bombs landing on suspected positions. Due to the safety of the tunnel, however, only minor damage was suffered.

Position of Annie's Tunnel Hideout

(Source: R O'Rourke, Anzio Annie, She Was No Lady, 1995).

What followed for the next three months was a cat and mouse game in deadly earnest, the mouse running to its hole when the cat approached. Well, it was some cat, and some mouse! Allied losses due to Annie were adding up. On 18 February, she destroyed a harbour utility vessel and damaged a destroyer and a freighter. This forced the supply ships 5km out to sea to avoid being sunk. The British cruiser, Mauritius, was ordered to take Ciampino rail yard under shells, but she would not take the risk and, with her 24km range, could not take out Annie in any case.

On March 9, using air reconnaissance photographs, Annie fired eight shells at night and took out a fuel dump, causing a massive fire that lasted for three days, setting back the Allied effort for more than a month. Thus the game of hide and seek continued for almost three months, without for almost three months, without the 'Annies' suffering any damage at all.

By then, Allied reconnaissance planes had noticed two 'Annie' guns at Ciampino rail yard, covered with camouflage netting, and an attack by eight P-40 planes carrying 250kg bombs followed. The aircraft reported direct hits on two guns and the destruction of the rail link Borcherds heard over the radio that he was probably dead and his guns destroyed. It sounded good, but in fact the Annies were safely in the tunnel and the attack had merely destroyed two wood and iron dummy guns. It was the way that dummies worked! After the attack, Annie fired four rounds to show that she was alive and well, and the next day sank a liberty ship to emphasise this.

Clark was exasperated. Annie's threat was also psychological, and the troops lived in constant fear of the next shell from Annie. The scream, 'Here comes Annie', sent the GIs running for cover. The shell's passage was compared to a freight train passing overhead and blasting a hole big enough to swallow a Jeep. It paralysed the thought and actions of the men. Once, the glint from an officer's white map board drew fire from Annie and the story went around amongst GIs that you could not even talk to each other without Annie chipping in. Veterans said that Annie was as timely as a Swiss watch. General Mark Clark, in his memoirs, mentions the harrowing sound of the shells as they roared overhead, causing him many sleepless nights.

Allies fight back

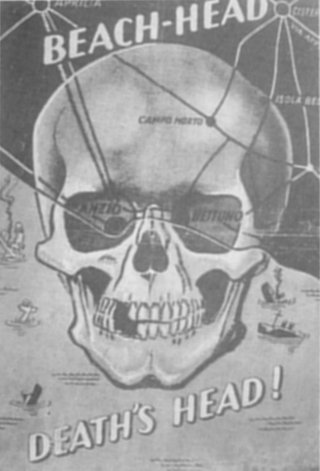

General Lucas then launched a strike force to cut the German supply routes and at the same time take out Annie. It was a disastrous failure, with only six men of the attacking force of 767 returning, the rest being lost or captured. The Germans responded with a counter-attack in strength, hoping to drive the Allies off the beach, but due to massive bomber attacks from Cassino, supported by artillery and broadsides from two cruisers, the attack petered out and the beachhead held, even if precariously at times. The Allies were actually being driven back, if only metre by metre, and the ghastly spectre of an ignominious withdrawal actually loomed at times, but they held on. The Germans knew this and exploited the discomfiture of the Allies by dropping a special pamphlet behind their lines.

A German propaganda poster dropped at Anzio

(Source: Purnell, History of the Second World War, 1973).

The two Annies could not really stop the Allies, but this might just have been possible with, say, six. At one stage, things really looked bad for the Allies and General Lucas, who showed signs of despondency, was replaced by General Truscott in an attempt to instil more stamina.

The tunnel puzzle remained unsolved and more air photos were requested in order to pinpoint Annie's position. This effort was seriously hampered by the German flash simulators and other deception measures.

The Annies' performance depended, of course, on regular ammunition supply and every day three rail trucks with shells and powder arrived from La Spezia. At times, the rate of firing was curtailed by the lack of ammunition, giving the Allies some much-needed breathing space.

The notches on Robert and Leopold's barrels grew in number as the guns picked off more targets, concentrating on ammunition dumps. On one day alone, they destroyed 182 tons of ammunition; on another, 353 tons of ammunition; and on yet another, they took out 233 tons of ammunition and 5 000 gallons of petrol and sank an LCT in the harbour. They once engaged and severely damaged a destroyer and a freighter at a range of 50km. In one month alone, the two Annies took out 1 500 tons of badly needed ammunition, but by then their hits on ships had been reduced, since these targets anchored 10km out at sea, keeping them out of the Annies' range. On one day in particular, Borcherds fired 72 shells, the pinnacle of the Annies' bombardment achievement and, by the end of April 1944, they had fired 5 523 shells onto the beach. Some fragments of an Annie shell were recovered and identified by a British officer as the type of shell fired on Dover, either 280mm or 350mm. By then, no dud rounds had been salvaged.

It is impossible to determine the extent of the damage or casualties caused by the Annie guns, but certainly it was enormous. Their objective was not the troops as such, but ammunition dumps, fuel dumps, vehicles, ships, and harbour installations. Unfortunately, the exact count of the number of these taken out by the Annies is not available. However, the disruption of the beachhead organisation and logistics, and the discomfort and fear induced in the troops, were some of the nonmeasurable objectives. On 2 May, the Annies fired eighteen shells on shipping, 10 to 12km out at sea, but they did not succeed in sinking any.

The operation of both Annie guns was often slowed down due to ammunition shortages. At one stage, the Annies suffered a severe shell shortage due to the bombing by Allied aircraft of the shell factory at La Spezia. Their inventory, at one stage, was down to a mere thirteen rounds. This resulted in a silence of 21 days in April 1944, much appreciated by the men on the beach.

Solving the Annie mystery

The Americans introduced the Black Dragon gun, which had almost the range of their Long Tom, but with a heavier 160kg shell. They also had two 200mm guns, with supercharged ammunition, that could have reached Annie, but again the effort was hampered by lack of knowledge of her exact position. The Long Toms pounded her suspected positions, one battery firing 3 240 shells in one day. More reconnaissance flights were requested when it became obvious that the Annies were still not being destroyed, despite many claims to the contrary. Eventually, a dud shell was excavated and examined, so at least the calibre of Annie became known, but this information did not make much of a difference.

Raiding parties were sent forward in an attempt to take out the Annies. Operation Ginny was launched to destroy rail connections between Genoa and La Spezia, thus hoping to stop supplies from reaching the Annies' sector. The first raid, scheduled for 27 February, was aborted and the second was cornered within days and the raiders captured.

By then it was suspected that the guns could be in caves - but where? It remains a mystery why Allied intelligence, aided by local informers, was still unable to discover the Annies' position. Eventually, almost by chance, fighter planes discovered the Annies' lair when panicking men fled into the tunnel. The game was up.

The suspicious tunnel was raided, with fighter-bombers dropping heavy bombs, and the French cruiser, Emile Bertin, firing 350 rounds in three days at the hideout. With both guns way back in the tunnel, however, only the forward-placed kitchen cars were damaged. From the gunners' point of view this was, of course, a serious matter as it interfered with their meals. On 13 May 1944, the Allies broke through at Cassino, and advanced towards Rome. With the hideout discovered, and with the increasing Allied aerial and ground strength, Filzinger decided to remove the guns. As in chess, the endgame was now being played, and he either had to evacuate or lose the guns.

On 18 May, Leopold and Robert fired their last sixteen rounds and then escaped after dark along the coastal rail route into the rail yard in Civitavecchia, in preparation for evacuation towards Rome. The net was closing, however, and escape became impossible. With a heavy heart, Sergeant Sauerbier decided to destroy the guns that had served him so well. Time was running short, with the Allies advancing, and he only managed to blow up the breech blocks and elevation generators before he himself escaped towards Rome. In a way, this was fortunate for posterity, for both guns were thus saved for future generations to admire.

Annie captured. Here the remains of the camouflage covering can be seen.

(By courtesy National Air & Space Museum - USA).

Three days after Sauerbier had spiked the guns, there followed the first successful raid on them. Their entire train was bombed in Civitavecchia yard, the locomotives and the cars overturned, and the guns damaged. The Anzio Express had made its last run. General Truscott, unaware of this development, had already decided on a masterstroke to take out the guns with massive aerial bombardment of the tunnel. Two days after the capture of the guns, bombers with 5 000kg Tallboy bombs blasted the tunnel, one bomb penetrating the tunnel roof through 25m of earth before exploding. The tunnel was now useless and the hideout destroyed, but the guns were gone. Leopold and Robert were already in Allied hands, and soldiers climbed on them like children with a new plaything, or like big game hunters who had bagged two rogue elephants. Officers of all ranks flocked to the yard, and everybody started picking off souvenirs until guards were posted. Only then was it realised that there had been two guns, and not one Anzio Annie as everybody had thought.

The aftermath

The cost in men had been terrible. The Anzio landings left behind 20 900 Allied, and 10 300 German, casualties - another example of defence having the edge in this type of warfare. Fortunately for posterity, the Americans decided not to destroy the guns as they had done with Heavy Gustav, but to send them to the USA for evaluation. In fact, Leopold and Robert are the only remaining K5 E guns in the world. They signify the end of the era of the railway gun - the last of the dinosaurs. But only Leopold emigrated to America. Robert stayed in Europe and is now on permanent exhibition at the Atlantic Wall Museum at Cap Griz Nez in France, installed next to the Batterie Siegfried gun emplacement. Leopold arrived in Taranto some months later and, by means of a crane and a barge, was loaded on to the liberty ship, Robert A Livingstone. On 6 July 1944, she docked in New York and, in September the same year, Leopold arrived at Aberdeen Artillery Proving Ground, where, today, it remains on permanent display. It is a fitting resting place for one of the most famous guns in the world.

Thus ended the Anzio Annie saga. It was a classic example of how two guns of excellent design, well positioned, well served, and well camouflaged, held an army to ransom for more than three months, and almost succeeded in getting the better of it. Second World War veterans on both sides, maybe for different reasons, will always remember Anzio Annie.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bishop & Warner, German Weapons of World War Two (Grange Books, Kent, 2002).

Engelman, J E, German Railroad Guns in Action (Squadron/Signal Books, Texas, 1976).

Hamberstadt, H, The World's Greatest Artillery (Amber Books, London, 2002).

Hogg, IV, German Artillery of World War Two Greenhill Books, London, 1997).

Hogg, IV, Twentieth Century Artillery (Prospero Books, Ontario, 2000).

Hogg, IV, The guns of World War II (Purnell Books, Abington, 1976).

Hogg, IV, Encyclopedia of Ammunition (Apple Press, London, 1985).

Mayer, IS, The Best of Signal (Bison Books, London, 1985).

O'Rourke, RJ, Anzio Annie, She Was No Lady (Fort Washington, Maryland, 1995).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org