The South African

The South African

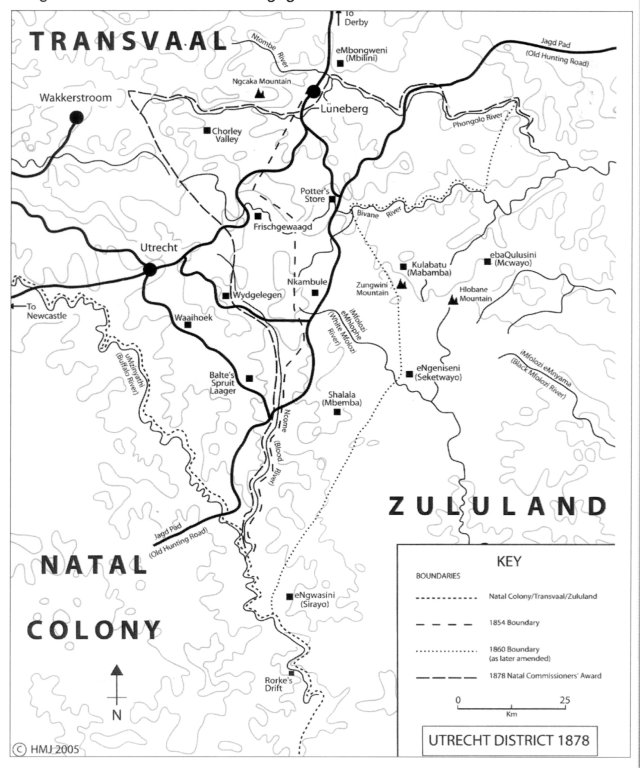

In 1879, the small village of Utrecht and its surrounding district was the most remote administrative unit of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR), bordering Natal to the west and the Zulu country to the east. Its turbulent internal history over a short period of some thirty years and quixotic relations with the neighbouring Zulu polity played no small part in the genesis of the Anglo-Zulu War that started on 11 January that year.

Topography and early inhabitants

Topographically, the Utrecht district included the upper Phongolo basin, the Balelasberg to the south and the lands beyond sloping down to the Mzinyathi (Buffelsrivier/Buffalo) River. About the mid point of the nineteenth century, the basin and hills to the east were occupied by royal Swazi refugees, Nyamayenja waSobuza and Malambule waSobuza as well as the Mazibuko under Phutini kaMatshoba. In the south were the Hlubi, controlled by Mthimkhulu kaBhungane from his homestead, Nobamba, near the future site of Utrecht village. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a sequence of events generated primarily by unusually prolonged droughts, subsequently labelled the Mfecane, had completely changed the political landscape ofthe area. Initiated by the Ndwandwe of Zwide kaLanga, more aggressive control over natural resources generated several military engagements and the subsequent rise in political influence of Shaka kaSenzangakhona, a mercenary commander of a section of the Mtetwa forces of Dingiswayo kaJobe.

Aided by Dingiswayo, Shaka usurped the leadership of his own small Zulu group and then consolidated his hold on neighbouring polities. The efforts of Shaka and his successor Dingane kaSenzangakhona permanently to extend their influence north of the lower Mfolosi were largely ineffective. It was the third leader of the nascent Zulu polity, Mpande kaSenzangakhona, who first threatened the people of this area from 1841 onwards. And he soon came to rely on the influence of a new political power source, the trekboers who had first tried to settle south of the Thukela and then been forced by the British back over the Drakensberg. Whilst the majority of burghers settled on the highveld around the political foci of Potchefstroom and Ohrigstad, several families remained in the Klip River area. Mpande's attempts to involve the British in his plans for expansion to the north-west proved fruitless and he came to rely on A T Spies and burghers from Klip River who were negotiating with him to free their area of British control. Mpande also opened contacts with A H Potgieter in Ohrigstad and in 1847, when his promised support for a coup against the Swazi heir proved ineffective, Malambule was induced to settle south of the Phongolo. In February 1848, Mpande was emboldened to force the Mazibuko and Hlubi to withdraw south of the Mzinyathi into British-controlled territory. The Zulu made no attempt to settle the lands thus vacated north and south of the Balelasberg. About this time Mpande consolidated his north-western frontier by moving the principal homestead of the Qulusi people, ebaQulusini, to the northern slopes of Hlobane Mountain and associating with it remnants of smaller groups such as the Mazibuko, Zwane, Khumalo and the Swazi refugees.

Two closely related Zulu sub-groups were also moved the Mdlalose to between the Ncome (Blood) River and Mfolosi Mhlophe (White Mfolosi) River under Sekhetwayo kaMdlaka, and the Ntombela to the lower Bhivane valley under Lukwazi kaMagwana. The peoples living beyond acknowledged either Swazi or Zulu hegemony as circumstances dictated; north of the Phongolo Swazi control was acknowledged by all.

A T Spies (Source: Utrechtse

Eeufeesgedenkboek,1854-1954).

Advent of the Trekboers

The vacuum left by the departure of the Hlubi did not go unnoticed. Dik Cornelis (C J) van Rooyen from Olifantsklip in Weenen district secured the agreement of Mpande to farm north of the Mzinyathi, a claim strongly repudiated by later Zulu authority. Boer settlement in this area was a process complicated by internal political and religious rivalry. Not the least of these was the fact that van Rooyen was also acting as the agent of A J Pretorius, president of the ZAR, in his attempts to secure a coastal outlet for his land-locked republic. News of the reported grant of land in August 1852 brought burghers flocking to the Buffelsrivier Maatschapij, as the early settlement was known, among the first being J C Klopper and later Spies who had left Klip River to farm near Lydenburg. Concern about the security of their title to the land led the residents to negotiate with Mpande and an agreement was concluded with him on 8 September 1854. In effect the boundary as defined excluded the upper Phongolo basin and in practice the line of the Jagd Pad, the hunting road connecting Natal with the Swazi country avoiding Zululand, became the de facto eastern boundary of the community. The ZAR refused both to recognise and absorb the district of Utrecht as it was named in 1855 and the Lydenburg Raad also withheld approval. However, religious schism and personal rivalries resulted in amalgamation with the Lydenburg Republic.

C J van Rooyen (Source: Utrechtse

Eeufeesgedenksboek, 1854-1954 ).

Early relationships with the Zulu were subordinated to the intense struggle for power between Cetshwayo kaMpande and his brother Mbuyazi that culminated in the former's success at Ndondakusuka in December 1856. Mpande's physical decline in the following years allowed Cetshwayo to dominate the politics of the Zulu state. Initially he sought Boer assistance in legitimising his claim to succeed his father and asked M W Pretorius to perform the same function that his father A J Pretorius had performed for Mpande. Overanxious that the apparent claims of a younger brother were about to be recognised, Cetshwayo ordered the killing of the boy and his mother. The attempt was badly botched, his father's residence violated, the mother publicly hunted and murdered and the boy forced to flee to Waaihoek in Utrecht district for sanctuary with two izinduna, people and cattle. The return of the refugees, Cetshwayo's initial offer to extend the eastern boundary of the district and his subsequent denial of any involvement were part of a long, complicated series of negotiations over the next fifteen years. With his father still alive, Cetshwayo needed a cause with which he could be identified. In the absence of a suitable neighbouring African polity that would have provided a focus in earlier years, a group of weak, disunited Boers with no major political backing provided a suitable substitute. Northern encroachment became one of his policies from about 1861 onwards as the emGazini people crossed the Phongolo into Swazi country lately ceded to the Boers. Further west the Qulusi did likewise, and Zulu settlers now streamed into the areas apparently ceded to the Utrecht farmers. In June 1868, Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza arrived at eKhombela mission, west of the German settlement around Luneburg and north of the Phongolo River in Wakkerstroom district, with instructions to take control of the area. For the Utrecht burghers the amalgamation of the Lydenburg Republic with the ZAR (and thus of their district) complicated relationships with the Zulu, bringing strangers to discussions about land cessions solely concerned with Pretorius's continuing attempts to establish a maritime outlet on the eastern littoral.

After the death of the Swazi ruler Mswati II in 1865, his eldest son Mbilini attempted to succeed, but was forced into exile, taking refuge eventually on Mbongweni Mountain overlooking Luneburg. As a royal refugee, he was welcomed by Cetshwayo and lived at Ondini for two years. In an area whose inhabitants, black and white, were living in a state of considerable unease, Mbilini heightened tensions by frequent cross-border raids. These became the focus of negotiations between Cetshwayo, who had succeeded on his father's death in late 1872, and G M Rudolph, appointed landdrost of Utrecht in January 1874. Rudolph was an able administrator, developing close relationships with the Zulu by whom he was highly regarded.

British Annexation

With the British annexation of the Transvaal in April 1877, the politics of the north-western Zulu border changed dramatically. No longer able to play off British and Boer, Cetshwayo was now faced solely with the British in the person of Sir Theophilus Shepstone, the erstwhile Natal secretary for native affairs, now Transvaal administrator, whom he despised. Shepstone inherited a confrontational situation in which farms along the Jagd Pad in the face of Zulu threats had been abandoned and looted. Cetshwayo was, however, hopeful that prior British coolness to Boer territorial claims meant that Shepstone would immediately support Zulu expansionist ambitions. At a meeting at Conference Hill south of Utrecht in October 1877 with Mnyamana kaNgqengele Buthelezi and large number of leading izinduna, Shepstone's failure to announce a boundary settlement and agree with pretentious Zulu land claims caused bitter resentment. Cetshwayo intensified his aggressive posturing in the upper Phongolo basin causing Sir Henry Bulwer, the lieutenant-governor of Natal, with the backing of the high commissioner Sir Bartle Frere, to initiate a process of arbitration. Shepstone could only concur and the Transvaal was effectively removed from control of the border situation. Bulwer appointed three commissioners from Natal to elicit the facts and the Transvaal and the Zulu were invited to send representatives.

In late 1877 the tiny village of Utrecht had become the de facto seat of the Transvaal administration. From here, without staff, records or any of the other appurtenances of government, Shepstone tried to prepare a case for the boundary line demarcated in 1864, one that he had come to believe had validity. Sitting at Rorke's Drift in March and April 1878, the Natal commission forced the Transvaal to establish the case for the 1864 boundary, the Zulu representatives being allowed to go no further than deny anything the Transvaal witnesses said. Only one of the Natal commissioners had ever visited the area in question, Lt-Col A W Durnford, RE, who had made a brief reconnaissance of the border district in May 1877.

This had clearly not been part of his military duties, then concerned with establishing a British military presence in Pretoria, and was probably made at the behest of Bishop Colenso, a supporter of Cetshwayo's territorial ambitions and with whose daughter Durnford had formed a strong attachment. It was Durnford who wrote the commissioners' report and drew the maps. In London, a senior civil servant forecast that the 'enquiry will be a farce' and so it turned out. The vague line recommended by the commission was one never before discussed, but it followed precisely the one that Cetshwayo had laid down as his north-western boundary. Utrecht district below the Balelasberg was accepted as a de facto settled area, but the land to the north of the Klein Bloed Rivier including the whole of the upper Phongolo basin was declared Zulu territory.

Frere realised that the commission's proceedings had been slanted against the Transvaal, its report filled with factual inaccuracies, and its findings the germ of further conflict rather than its resolution. A political realist, however, he accepted its conclusions from the start after assuring himself of the meaning of several of the report's ambiguities. Rather than Frere's prevarication, publication of the conclusions was delayed by Bulwer's bureaucratic incompetence and insistence on secrecy. Bulwer sent the report and accompanying documentation to Frere on 15 July. On the following day he sent the report alone to the colonial office which considered that without the maps, minutes of evidence and documentary evidence, no satisfactory opinion as to the validity of its conclusions could be formed. On Frere's insistence, Bulwer eventually sent the report to Shepstone for comment on 26 August, but again without supporting documentation. The Zulu were never consulted. By the time publication for the findings arrived, Frere had prepared his case for war with the Zulu and they were announced simultaneously with the contents of the 'Ultimatum' document.

British Preparations for War against the Zulu

As it had been the focus around which discussions of a contentious boundary had escalated into open hostility and been seized upon as the pretext for war, Utrecht now became an important focus for the prosecution of those hostilities. Already during 1877 and 1878 it had been an important British garrison (the 80th [Staffordshire Volunteers] Regiment and the 90th [Perthshire Volunteers] Light Infantry). In Lt-Gen Thesiger's (later Lord Chelmsford) plans for an invasion of the Zulu country, Utrecht was one of the five starting points and it was there that he posted Lt-Col E H Wood VC, in September 1878. As commandant, Wood found a village of 248 white inhabitants, 56 being men capable of bearing arms; in the surrounding district there were some 1 600 white people, of whom 319 were men capable of bearing arms, and some 3 000 Africans. The district had four laagers at Utrecht, Balte's Spruit, Burghers' Laager on the Bhivane River, and Luneburg north of the Phongolo River in Wakkerstroom district. Wood immediately began to purchase waggons, oxen and maize. Mbilini attacked homesteads in southern Swaziland in early October dramatically escalating fear throughout the communities, but particularly around Luneburg. Here Zulu messengers arrived shortly afterwards telling residents to leave within three days. Wood ordered two companies of the 90th Regiment to their defence and Maj C F Clery was posted as local commandant. Military stores began to be moved from Newcastle to Utrecht, parties of soldiers started improving local waggon routes, laagers were strengthened and new forts constructed.

Participation of Local Residents

In addition to establishing his commissariat, Wood was also concerned to seek assistance from local burghers. For this purpose he visited Swart Dirk Uys and field cornet P F Henderson in Wakkerstroom as well as A L (Rooi Adriaan) Pretorius on his farm Welverdiend in the Versamelberg. Bitter opposition to British annexation precluded burgher cooperation. Civil and military relations in Utrecht village were poor. Wood had arrived with considerable misconceptions as to his legal status in the ZAR and was rapidly disabused of the idea that orders and laws obtaining in Natal applied in the Transvaal also. Rudolph ordered Wood to remove his tents from the streets and warned him not to interfere in the laagers which belonged to the burghers. N M MacLeod was appointed civil and political assistant for Utrecht district and the Swazi border without the knowledge, let alone the approval, of Shepstone and the Transvaal government. With orders that seriously impinged on the landdrost's authority and that of the Transvaal secretary for native affairs, this was just one example of the high-handed approach taken by Frere and Chelmsford. Not unnaturally, the Swazi ngwenyama Mbandzeni would not recognise MacLeod, whilst Chief Justice J G Kotze refused to give him any 'commission empowering him to act magisterially' in the Transvaal.

Having failed elsewhere, Rudolph convened a meeting in Utrecht on 4 December for Wood to'make proposals for burgher participation in what was regarded as an inevitable war. Senior officials and prominent citizens attended from both Utrecht and Wakkerstroom districts and Wood received indications that some support might be forthcoming. Whilst Wood might expect voluntary white participation, he was anticipating the need to impress Africans. But his insistence on the declaration of martial law was rejected as being a concept not recognised in ZAR law. Instead, the provisions of the Krijgswet were used to instruct field cornets to prepare lists of burghers who could be enrolled. The boundary commission, however, had held open sittings and, from the conduct of the enquiry, it was evident to all that the Zulu claims would succeed. This vitalised Zulu confrontations and hardened the burghers against helping the British. 'Why should they be asked to fight in the interests of Natal when Transvaal interests were being handed over to the Zulu?' was their reaction.

Only those burghers with a personal agenda were prepared to fight and even they would not accept payment from the British. At the head of a small unit called The Burgher Force was Petrus Lafras Uys who had no respect for the British, but fought because his father and brother had been killed by the Zulu and because his farm Wydgelegen was 15km south-east of Utrecht and just within the boundary designated by the Natal commissioners. He brought his four sons and they were joined by the Combrinks, Meyers, Craigs and van Rooyens (closely related by marriage), the landdrost's brother J Andries Rudolph and the Rathbones from Chorley Valley. Some 35 burghers served with the Burgher Force, but only twenty-seven names have been identified and are appended to this paper. Others would not cooperate and there was a breakdown in the civil administration. Field cornets resented being ordered to prepare lists of burghers as commandeering was widely rumoured and Lukas Meyer, Naas Ferreira and Louis Viljoen left their wards with their families and stock and trekked north. Further meetings of burghers failed to elicit positive assistance.

Wood's attempts to impress Africans met with similar rebuffs. An early proposal to recruit Africans was rejected outright by Shepstone on the grounds that the male members of the sparse population living mostly on farms would be loathe to leave their families exposed to Zulu attack. Before Shepstone's response was received, Chelmsford ordered Wood to organise a levy to be called 'Wood's Irregulars' (WI) and Frere was forced to use his political weight to lean on a most reluctant Shepstone whose administrative position and political standing he was steadily undermining. Local opinion was against arming Africans, but on return to Utrecht on 23 December from a visit to Pietermaritzburg, Shepstone was forced to give in to another request from Wood and on Christmas Day gave the landdrosts of Utrecht and Wakkerstroom authority to furnish Wood with the force of up to 2 000 Africans he demanded. Local whites were recruited as officers, the prime criterion for selection being the ability to speak siSwati/isiZulu.

Commanding the 1st (Wakkerstroom) battalion of the WI was field cornet P F Henderson. Other officers included Edward Hazelhurst, proprietor of the Travellers' Home Hotel in Wakkerstroom, A M J Laas who had been prominent in negotiations with both Swazi and Zulu, and L P Henderson. The 2nd (Utrecht) battalion was initially commanded by W von Linsingen, but he was soon replaced by R G Roberts, Rudolph's clerk/interpreter, with T L White, P Mare and C J Hook as company captains.

Commandeering proceeded at a brisk pace. On New Year's Day 1879, 50 mounted and 200 dismounted men of the 2nd Bn left Utrecht for Column No 4's assembly point at Balte's Spruit. On the following day, some 300 men from Wakkerstroom arrived in Utrecht on their way south.

Advance into Zulu land

Wood had a limited number of imperial troops from which to assemble his No 4 Column for the advance into Zulu territory. At Utrecht was the 90th Light Infantry, two of its companies having been moved to Luneburg to protect that community before being relieved by two companies of the 13th (Somerset) Light Infantry (LI) who were in turn relieved by the arrival towards the end of December 1878 of the Kaffrarian Riflemen, a unit of mainly German volunteers recruited from the Eastern Cape under Cmdt F X Schermbrucker. The remainder of the 13th LI arrived in Utrecht 'all tattered and torn' after their long march from the Pedi country on 23 December. During that month, waggon trains with between 30 and 50 waggons constantly trundled between Utrecht and Balte's Spruit where Wood established his forward base. Early in the New Year, the 90th LI and the 13th LI left Utrecht for this base, leaving the village and the military hospital to be guarded by the residents and 100 men of the 13th LI, most of them 'non-efficients for campaign service'.

With typical disregard for diplomacy or its political ramifications, Wood took his column across the Ncome River into Zulu territory six days ahead of the expiry date of the British Ultimatum on 11 January. The column made its base at Shalala, a hill known to the British as Bemba's Kop. Here they were joined by Uys and fifteen mounted burghers as well as a contingent of the 1st Bn WI under Henderson. The Burgher Force was soon employed scouting towards the Mfolosi Mhlophe, coming across large numbers of Zulu in groups of 15-20 who told the burghers that they were out hunting.

With a keenness that did not escape notice or criticism, Wood's column was immediately engaged in seizing cattle. By 12 January, some 2 500-3 000 head had been rustled, a herd of 2 317 being sent back to Utrecht under Henderson with a note from Wood telling Rudolph to divide the herd into three groups, one to be held in Utrecht, one driven to Newcastle and the other to Wakkerstroom for sale at each place 'for the benefit of the captors'. Rudolph had neither the staff nor the inclination to accept such instructions and Henderson decided to trek on to Wakkerstroom with the complete herd. Not only was the landdrost annoyed, some burghers threatened to drive the herd back into Zulu country to forestall attempts by the Zulu to reclaim it.

As the British threat to the northwestern Zulu frontier became patently obvious in late 1878, Mbilini assumed control of preparations for its defence on the Zulu side. As the only commander pitted against the British who had had any military training or experience, he was particularly well suited to this topographically open frontier, bringing with him a familiarity of Swazi military strategy and tactics.

In mid-December, he not only controlled the Qulusi, essentially a group of Swazi refugees, but also the Ntombela and Mdlalose as well as the Kubheka under Manyonyoba waThulasizwe who lived north of the Phongolo near Luneburg, essentially in the rear of Wood's column. On the concentration of British forces, Mbilini ordered people, cattle and food stocks to retire into the hills, principally Hlobane Mountain, and he left his Mbongweni homestead for another of his residences, Ndhlabeyitubula, close to Hlobane.

The First Battle of Hlobane

Assuming incorrectly that the main force opposing him was concentrated on ebaQulusini, north of Hlobane, Wood directed his slow-moving column in that direction. On 24 January, it arrived at Zungwini's Nek, between Zungwini and Hlobane Mountains, where it came under heavy and accurate fire. After a short, inconclusive engagement which became known as 'The First Battle of Hlobane', the British and Qulusi respectively withdrew to their local bases. It was during this engagement that a runner brought news of the Isandhlwana debacle. Wood's response was to set his ponderous column in motion once more and, after a week of indecision, to establish camp on the Jagd Pad at kwaNkambule (Khambula), high on the hills between Zungwini and the Skuurweberg (Nqaba kaRawana). Strategically this was an inept location that provided neither cover for the exposed districts of Utrecht and Wakkerstroom in his rear nor a commanding view of the country through which it was intended he should advance. There was little activity save for routine patrols, sports days for the imperial soldiers and short moves of the camp to more salubrious locations. Here his mounted force became further depleted by the refusal of 72 troopers of the Frontier Light Horse to extend their contracts. From Hlobane, Mbilini mounted raids directed against places from which it was known that large numbers of African residents had been impressed by the British, one on 10 February with an impi 1 500 strong against homesteads in the upper Phongolo basin well in the rear of British forces.

Relations between the WI levies and their officers were far from satisfactory and in early February the majority of the 1st (Wakkerstroom) Bn, instead of returning to Khambula after an infructuous raid on the Kubheka, simply went home taking their rifles, horses and blankets with them. The result was closer imperial control, Maj W K Leet (13th LI) being appointed corps commandant. Henderson, Enoch Klopper and other locals were dismissed and replaced mainly by English militia officers. Wood was also failing to control the drunkenness then rampant in and around Utrecht of imperial, colonial and African soldiers under his command. Night scares caused by drunken soldiers discharging their firearms, the burning of houses and occasional riots later gave Chief Justice Kotze cause to question the efficiency of military discipline in the district.

Despite his apprehensions at Wood's activities and his personal grief following the loss of a son at Isandhlwana, it was on Shepstone's instructions that Wood's column was reinforced with the irregular horsemen that it badly needed to become operational. The Transvaal Rangers under Cmdt P E Raaff had reached Middelburg on their way to campaign in the Pedi country when they were diverted to join the column being formed by Col H Rowlands VC, at Derby and later, in February, Wood's column at Khambula. Shepstone also ordered B Troop of the Border Horse, raised for service against the Pedi, to leave Pretoria post-haste for Makati's Kop south of Luneburg. But these activities were not enough for Frere and, in February, Shepstone was replaced as administrator of the Transvaal by Col W O Lanyon.

The Second Battle of Hlobane

On 12 March, as dawn broke, Mbilini struck again behind Wood's position, attacking a British supply convoy guarded by imperial troops and laagered at Meyer's Drift east of Luneburg, waiting for the swollen Ntombe River to subside; 79 soldiers and civilian conductors were killed and arms and ammunition were seized. Wood's only response to this lapse in his control of the area was to lead, in person, another raid against the Kubheka, achieving little except burning abandoned homesteads and empty mealie fields. This expedition took three days and, on the night he returned to Khambula, 26 March, Wood determined to mount what he called a 'reconnaissance' to Hlobane the following morning. The mountain had been under close observation for several weeks and it was known that it was difficult to access, rendered even more so by walls of stone newly erected by the Qulusi. It was also known that on the well-watered plateau there were thousands of head of cattle. The reasons for Wood's sudden decision to mount this assault, for such it really was, are unclear. Chelmsford had suggested a demonstration about this time, but Wood made no reference to that point in his official report. Only later, when news of the severity of his defeat at Hlobane on 28 March became widespread, did Wood insist that he had moved only on Chelmsford's orders, a point repudiated by Chelmsford himself.

Rowlands, by this time, had been banished to Pretoria and Wood's column strengthened with the units that had been under his command. With the exception of sections of the Royal Artillery, Wood refused to engage imperial troops and used only his impressed African levies and colonial irregular horsemen, the Burgher Force among them, against the Qulusi on Hlobane. The propensity of Wood's column to rustle cattle has been noticed and it was certainly the means to supplement the pay of colonial troops. Some, if not all, of the burghers who rode with Uys thought hat acquiring cattle was the main objective with at least the tacit promise of a reward of farms. Henrique Shepstone, the former administrator's son and Transvaal secretary for native affairs who was in Utrecht at this time, blamed Uys for urging Wood to make the assault. A local history subsequently noted that Uys had opposed the attack and predicted danger.

It is more likely that it was Maj R Buller, in overall command of the horsed detachments in the column, whose pugnacious character and concern for the welfare of his own unit, the Frontier Light Horse, persuaded Wood to assault Hlobane.

The Burgher Force, comprising 32 burghers, were part of a column led by Buller which also included the 2nd (Utrecht) Bn WI with 277 levies. The 1st (Wakkerstroom) Bn WI of240 levies, now commanded by 2nd Commandant T L White, formed part of Lt-Col J C Russell's western column together with Hamu's People, lately impressed from those who had fled Zulu land with Hamu, commanded by Capt C A Potter. Uys and the burghers led Buller's column from the Nkongolwane valley up to Ityenteka Nek on the eastern side of Hlobane. The African levies with Roberts and Potter, both local men who knew the mountain well, led Russell's column up the western end of Ntendeka or Little Hlobane. Some 2 000 head of cattle were soon seized by Buller's column and driven along the flanks of the mountain by the levies to Ntendeka and down to Zungwini's Nek. When this operation was well under way, Mbilini ordered his force up on to the plateau of Hlobane from the flanks and from Ityenteka driving Buller's units westwards and cutting off their line of retreat. Their only hope of escape was down a steep, narrow and rocky krantz at the western end and here there were chaotic scenes as men and horses jostled to evade the fast-approaching Qulusi.

Despite the panic at what soon became known as "The Infernal or Devil's Pass', just seven of the total of some 200 who died in The Second Battle of Hlobane were killed here. Among them was Piet Uys, stabbed between the shoulders with an assagai as he reached the foot of the krantz. The principal casualties were the horses, the four Uys brothers escaping on their two remaining horses, whilst other burghers were forced to share mounts. During the course of the morning, a large Zulu impi was seen to the south, crossing theMnyati range, moving in the direction of Khambula. Apart from cutting off isolated groups south of the mountain, this impi had virtually no impact on the course of the battle, save to provide Wood with exaggerated excuses for the disastrous situation into which he had led his colonial and African troops.

Casualties among the African levies were relatively light, except among Hamu's People (80 to 100 killed). Not only had they recently been impressed and were thus quite untrained, but they also seem to have failed to hear the orders to abandon the cattle and make for Zungwini Mountain; as recent defectors, they were also a likely target for revenge. Their commandant, Charles Potter, whose father ran the nearby store at the Jagd Pad crossing of the Pemvane River, was the only other local casualty, killed while still leading his force in the vicinity of the later Tendeka railway station.

That evening, most of the burghers were given permission by Wood to leave for Utrecht and their homes. Whilst the white officers and their men had struggled back to the safety of Khambula laager, the African levies had been left to fend for themselves. Angered at being left unprotected during the retreat and apprehensive at the presence of a large Zulu impi nearby, the levies, waggon drivers and voorlopers also left that night, some making for Utrecht to report to Henrique Shepstone as did some of the burghers. Wood described them as deserters, hardly a suitable description from one so careless of their welfare. The Wakkerstroom landdrost, F S Hutchinson, refused to impress more African levies for Wood to replace those who had gone home; Henrique Shepstone supported Hutchinson, who told Wood that he lacked the authority to give him orders.

After the successful repulse of the Zulu attack on the fortified camp at Khambula on the following day, Wood spent the time compiling reports that were a mixture of confusion and deception. Mbilini ignored the activities of the impi and carried on with pre-arranged attacks heading north towards Dumbe Mountain with his own impi. Here small groups rendezvoused, were given orders and then split into two groups, one section moving up the Bhivane valley and the other up the Ntombe valley. Mbilini led the first group into the upper Phongolo basin, seizing some 3 000 head of cattle as he went. Several farms were attacked, including that of the Rathbones at Chorley Valley and those of the Kloppers, widow du Plessis and the Meyers. The other impi under Manyonyoba raided the Luneburg cattle kraal and burnt deserted houses including that of the Rabie family. The raiding lasted for several days until a British patrol from Luneburg intercepted a small group of Qulusi driving horses; in the pursuit, Mbilini was mortally wounded, but managed to reach his homestead at Mbongweni. Eventually, some burghers returned to Khambula where J A Rudolph was elected commandant, P L (Vaal Piet) Uys, Junior, having turned down his selection.

Aftermath

Chelmsford visited Utrecht in early May as he planned the second invasion of the Zulu country, but the focus of operations shifted southwards to Landman's Drift in northern Natal. The Burgher Force was posted to the Burgher's Laager to defend the area between Balte's Spruit and Luneburg. A composite WI battalion under White continued to serve with what now became known as Wood's Flying Column and participated in the battle of Ulundi on 4 July.

Although he sent a party to locate and bury Charles Potter's remains, Wood ignored the dead on Hlobane and it was left to J J (Kruppel Koos) Uys, his son Cornelius and P L Uys's youngest son, Dirk Cornelius, to climb on to Ntendeka to look for the remains of their relative in the following September. They found the skeleton, identified it by a waistcoat and knapsack, and brought it down to Wydgelegen for burial, later erecting a monument on the spot where he had fallen. Wood was, however, quick to initiate compensation for the Uys families on 13 April and title deeds to three farms in Wakkerstroom district were issued by Henrique Shepstone in February the following year. In 1883, a monument was erected in Utrecht from contributions made by burghers and soldiers who had fought in Wood's column. The end of the Anglo-Zulu War led not to peace in the area but to another tortuous phase in Transvaal-Zulu relations.

Composition of the Burgher Force

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org