The South African

The South African

by Emrys Wynn Jones

Wales, United Kingdom

In Part 1, the reasons for the British Government's decision, in December 1854, to raise a foreign legion to provide seasoned troops for the Crimea were outlined, and the process of recruitment and training discussed. The granting of a commission to Ensign Benjamin Simner in the 5th Light Infantry, British German Legion, was recorded. Four of the nine infantry regiments embarked for the Crimea in late 1855, but got no further than Scutari, where they spent several months.a When peace was declared the German Legion returned to barracks in Britain pending a decision as to their future. They did not take kindly to the tedium of barrack life, and there were incidents involving men of the Legion and soldiers from British regiments. Some legionaries went home, some settled in Britain, some emigrated to the Americas, and others awaited the terms that the Government might offer.

Badge of the 5th Light Infantry, British German Legion

(reproduced courtesy of the SANMMH).

When the Crimean War ended, the Government, left with a large force of mercenaries on its hands, began the search for employment for them, strongly urged to do so by the Queen, who was determined to obtain honourable treatment for her husband's countrymen (Panmure Papers, ii, p 150, The Queen to Panmure, 11 March 1856). In May 1856, Panmure sounded out Mr Robert Vernon Smith MP, the President of the Board of Control for the Affairs of India, about the possibility of employing men of the BGL in the Company's armies. He was confident that the men would welcome such an opportunity, and was 'satisfied that the tranquillity of its dominions and the honor of its arms would suffer no diminution by the introduction of these Troops into the Indian armies' (PRO, W06/196, Panmure to Vernon Smith, 1 May 1856). That tranquillity was soon to be rudely shattered, when many of the Company's native regiments mutinied and a conflagration spread rapidly through the territories under British rule in the plains of the Ganges and the Jumna.

At the beginning of April 1856, the Government sent Major J Grant, assisted by Captain Ernst Hoffman, DAQMG on Stutterheim's staff, to the Cape to study the possibility of stationing part of the Legion there to guard the eastern frontier. On his return, Grant submitted a substantial report to Panmure and, by September, a detailed scheme, with conditions of service drawing on Grant's recommendations, had been agreed (Schnell, 1954, 1999 reprint, p 60). The proposals took root quickly, the Queen was said to be gratified, and The Times welcomed the plan as one combining proper provision for the legionaries with improved security at the Cape. Hoffman, too, had returned, and on three successive days in September gave a detailed account of conditions at the Cape to the six regiments encamped at Colchester (Chelmsford Chronicle re-printed by The Times, 13 Sep 1856, p 9). The 5th Light Infantry attended on the third day, and we can be fairly certain that Ensign Simner was present with his regiment. Hoffman painted a glowing picture of life in Kaffraria in the eastern Cape - the equable climate, fertile soil, abundant water, absence of frost, and the warm welcome to be expected from the colonists - and advised the single men to find a wife before they left Europe.

The arrival of the British German Legion at East London, February 1857.

Oil painting by C C Henkel. (Reproduced with kind permission from the East London Museum).

Many followed his advice, and a remarkable number of weddings took place at Colchester and Gosport, aboard ships at Portsmouth (including 67 in one day on the depot ship, Britannia), on the voyage to the Cape, and in the settlements in Kaffraria. Unsurprisingly, given the haste in which it was done, many of the marriage records were questionable or incorrect and, to remove all doubt regarding their validity, the Cape Parliament passed an Act (Number 13 of 1857). Two Proclamations were made under its authority. The first, on 22 July 1857, contained what was intended to be an authoritative list of the legionaries and their wives, with the date and place of each marriage; the second, dated 12 January 1858, contained numerous corrections to the first.

Hoffman repeated the performance for the Light Dragoons in Aldershot, and the 1st and 3rd Light Infantry at Portsmouth. Many of the legionaries were not deceived by Hoffman's rhetoric, and treated his remarks with scepticism.

Disbandment

The Legion's disbandment took place in style at Wyvenhoe Park, near Colchester, on 30 September 1856. Stutterheim, now a major-general, reviewed all the regiments of the Legion, with the exception of the two stationed at Browndown under Wooldridge. After elaborate manoeuvres, directed by von Hake, he addressed the men from the saddle. Drawing a diplomatic veil over the disturbances at Aldershot, Plymouth, Gosport and Colchester, he thanked them for their good behaviour, urged them to accept the Government's terms for service at the Cape, and announced that he would be accompanying them 'considering as he did that it was a sacred duty to stand by them so long as he could do anything to promote their welfare' (The Times, 1 October 1856, p 7. Stutterheim did not stand by them for long, for in October 1857, to the dismay of Grey, he asked leave to retire and returned to Germany). By this time, little more than 7 000 of the original 9 000 remained on strength. That muster was further reduced by the departure of men who went home, were rejected for misconduct, settled in Britain or emigrated, and the contingent for the Cape eventually numbered little more than 2 300 men.

The vultures gathered rapidly. The King of Naples offered a bounty of fifty dollars to men who entered his service; the Dutch held out a premium of £5 to men prepared to join their forces in Batavia; and France and Argentina were suspected of designs on these 'soldiers of fortune'. Describing these approaches as 'a variety of underhand influences', the Thunderer' was blimpish, the burden of its complaint seemingly being 'how dare these foreigners make off with our foreigners?' (The Times, 1 October 1856, p 7). What did the Government offer to head off these blandishments? The terms to which Stutterheim referred at Colchester were published by the War Department on 24 September. They ran to 38 clauses, but despite the free passages for all ranks, the scales of pay (enhanced during periods of active service), the allocation of land and money for house building, and the right to unfettered title to such property at the end of seven years, the results cannot have been as Panmure, Stutterheim and the Governor at the Cape had hoped (The Times, 29 Sep 1856, p12; two clauses were added later).

Enquiries into the outbreak at Browndown progressed slowly. The first intelligence of the outbreak received at Horse Guards was a letter from Major-General H W Breton, commanding South West District, dated 22 October, as a result of which six ringleaders were tried by courts martial. It was not until mid-November that the General Commanding in Chief heard, in an anonymous memorandum, of any irregularity in the mode of carrying out the sentences. Major Charles Mills was ordered to investigate, and submitted his report on 18 November (PRO, W03/329. Mills was Brigade Major). Five of the six offenders had been publicly flogged in accordance with their sentences, but the sixth, a Private Duncker, was flogged 'privately and in a very irregular manner by order of the Lieutenant-Colonel and in direct disobedience of the orders of Colonel Woolridge [sic]'. To make matters worse, it was found that Duncker, who had been discharged from the Legion, had been restored to his regiment by von Hake, and had sailed for the Cape (PRO, W03/329 - two memoranda from Horse Guards, Major General G A Wetherall to Military Secretary, 26 November 1856 and 10 January 1857). Cambridge now informed Panmure of von Hake's misconduct and recommended his removal. Panmure concurred, and gave instructions that von Hake was to be removed from command of the 1st Regiment of Settlers (PRO, W06/113, Panmure to Lt Gen Sir James Jackson, 2 January 1857. The author is indebted to Stephanie Victor, Curator of the Amathole Museum, King William's Town, for information about Panmure's change of heart, and for her patience in answering his enquiries). He relented later after urgings from Stutterheim, who knew how useful von Hake would be in settling the Germans in Kaffraria.

Benjamin's father left a list of his son's letters, although the letters have not been found (Simner Family Papers [SFP]). Between 30 November 1855 and March 1856, he wrote eleven letters to his parents from Heligoland, the last of which, on 10 March, was written immediately before he left the island with members of his regiment. By 15 March, they were at Shorncliffe and his next letter, dated 17 March, bore that address. Later, after a brief stay in Aldershot, the regiment moved on 14 July to Colchester, and it was probably while he was there that he took the momentous decision to volunteer for the Cape. The record of Benjamin's movements kept by his father shows that on 31 October he had a private interview with the Duke of Cambridge at St James's. On 11 November, he received a letter from the War Department informing him that he had been 'appointed and selected for the Cape Rifles BGL' (SFP, 'Cape Rifles' is incorrect). He was to be one of 44 junior officers of the BGL who were designated as 'Gentleman Cadets'. They were to receive the pay and other advantages of non-commissioned officers, and would be liable to do the duty of NCOs when the Military Settlers were called up for service, but off parade they were to be free to associate with the officers 'upon an equal social footing' (PRO, W06/113, Panmure to Lt Gen Sir James Jackson, 2 January 1857; and W015/1, Nominal Roll of Gentleman Cadets who went out as Military Settlers at the Cape of Good Hope).

The Secretary of State for the Colonies, Henry Labouchere, had been corresponding with Sir George Grey, the Governor and C-in-C at the Cape, about the imminent arrival of this body of German Military Settlers, abbreviated to GMS, and now Panmure, aware of their somewhat anomalous status, and of the possibility that at some stage they might constitute a part of the Colony's armed forces, wrote to Lieutenant-General Sir James Jackson, the general officer commanding and Lieutenant Governor (PRO, W06/ 113, Panmure to Jackson, 2 January 1857). They numbered, he told Jackson, 2 309 officers and men, and were to be divided into three regiments. There were also 556 women and children. The force was fully equipped with arms, ammunition, tents and camp equipment, portable forges and tools. A quantity of clothing had also been shipped, but that was to be the limit of the department's generosity in the matter of clothing. Finally, Panmure told Jackson that, as the settlers were discharged soldiers, they would have to be dealt with under local enactments rather than the Mutiny Act or Articles of War. An Act 'for establishing more effectually the Settlement in this Colony of certain Military Settlers' was duly passed for this purpose (Act No 5, 1857, Cape of Good Hope, 29 June 1857).

To the Cape

During November, the GMS departed for the Cape in six sailing vessels - Abyssinian, Covenanter, Culloden, Mersey, Stamboul and Sultana - and HM steamer Vulcan, with Stutterheim and Wooldridge aboard. Benjamin departed for Gosport on

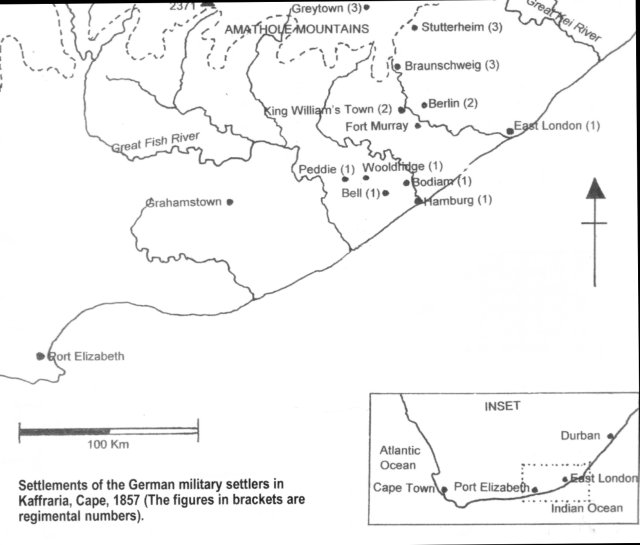

17 November and sailed on the Mersey two days later. His anxious parents were able to follow their son's voyage by means of reports by ships that spoke to Mersey, and thus learned that, on 28 November, she was off the coast of Portugal, on 9 January 1857, off the coast of Brazil in Lat 11°55'N, Long 32°4 TW, and that she arrived at Cape Town early in February. By the end of February, all ships had arrived at East London and, to avoid congestion, the Settlers were quickly moved inland to Fort Murray, some 50km up the Buffalo River, near King William's Town. By 9 March, all were assembled there, awaiting orders as to the location of their settlements. Three regiments were created, the 1st, under Wooldridge, establishing its camps along the coast from Peddie and Wooldridge in the west to Panmure and Cambridge in the east. The 2nd Regiment was commanded by the reprieved von Hake, but the following year, after a riding accident on his way to take the salute at a parade at Potsdam to mark the Queen's birthday, he died on 1 August 1858 and was buried on his farm at Berlin on 3 August. His death in Kaffraria was reported in The Times on 5 October as that of 'Colonel von Haken [sic], of the British Legion, a Waterloo hero who fought under Blucher'. His regiment settled along the line of the Buffalo and its tributaries, giving German names to its settlements, from Potsdam in the south to Wiesbaden in the north. The 3rd Regiment, under Lieutenant-Colonel Kent Murray, established settlements in and around the Amathole Mountains in the north, their principal station being given the name Stutterheim. By the end of April, Stutterheim was able to report that the GMS had all left Fort Murray (For the dispositions in this paragraph, see Schnell, 1954 [1999 reprint], pp 86-9).

Contemporary accounts of the appearance and conduct of the GMS covered a broad spectrum of opinion. Colonel E A Holditch, 80th Foot, ADC to Jackson, described the scene when, on 23 February 1857, Stutterheim reviewed the troops assembled at Fort Murray: 'At 3 pm Baron Stutterheim arrives & after luncheon at Col. M's [Colonel John Maclean, Lieutenant-Commissioner of Kaffraria] reviews the German Legion 1 700 - under arms - and a remarkably fine body of men, clean & steady under arms ... they promise to be good settlers.' (Boyden [ed], 2001, p 145).'

Settlements of the German military settlers in Kaffraria, Cape, 1857

(The figures in brackets are regimental numbers).

In November, however, Grey told the Colonial Secretary in a dispatch that 'although the German Legion contained many excellent men, it also included many desperate characters, collected from several nations, and that murders and unnatural crimes had been committed by some of them' (The Times, 14 July 1858, p 5). The crime sheet for the period between June 1857 and March 1859 recorded two cases of murder, two of culpable homicide, three of wounding and two of assault, unnatural crimes and theft. Less serious offences involving imprisonment reached a peak of eighty in May 1858 (Schnell, 1954 [1999 reprint], p 128). In fairness to the Germans, it has to be said that some of the worst crimes were committed by non-Germans, of whom there was a fair sprinkling in the BGL and the GMS, but the prejudice against the GMS as a whole had taken root. The King William's Town Gazette aired that prejudice in a letter that it published on 15 January 1859, shortly after a contingent of legionaries departed for service in the Indian Mutiny, saying 'No one in his senses would set down the recent importation of apparently honest and industrious Germans in the same list as the majority of the Legion ... The people of British Kaffraria have been, however, sufficiently experimented on to hold at a safe distance any who claim connection with the BGL. The recent deportation of a large portion is looked upon as a most providential occurrence by all good men.' Against that must be set the fact that as the regular forces at the Cape were thinned to provide reinforcements for India the presence of the GMS had come to be seen by Grey as an effective deterrent to insurrection in Kaffraria (Schnell, 1954 [1999 reprint], p 121).

Benjamin wrote his first letter home from Fort Murray on 12 March. Soon after the Germans arrived in Kaffraria there was adverse press comment about them and 'Lieutenant Simner of the 1st Regiment came forward in defence of the Legion' (Schwar & Pape, 1958, p 24). The rank given in the report may be erroneous, and it is likely that Benjamin remained a Gentleman Cadet - insecure, poorly paid, neither officer nor NCO, and precluded from hiring out his labour - until he left Kaffraria for India. It is possible that the reference to the 1st Regiment is also an error, for his father's list of Benjamin's letters refers to correspondence from Greytown and Dohne Post (Stutterheim) in the 3rd Regiment's territory, and his presence at Greytown is confirmed in a note in Schwar and Pape (1958), p 27, on the disposition of the Settlers. Benjamin's name appears in a list of the settlers in Kaffraria, as do the names of several of his brother officers in the former 5th Light Infantry. He does not appear, however, in the list of officers of the GMS to whom titles were granted for land and house, presumably because he did not return from India to rejoin the GMS for the remainder of his service.

Early in 1857 there was a crisis on the Cape's eastern frontier, and talk of an impending uprising by the local black population. In this outpost of Empire, decision-making was a solitary duty for the man on the spot, and duty's voice at times was indistinct. Uncomfortably aware that his forces were weak, Grey became convinced that the GMS must be part of the solution, but only if they could be kept in full military readiness. Acting on his own initiative, he decided to keep them on full pay, well aware that this had not been sanctioned. Predictably, Grey's decision pleased the colonists, but displeased his parsimonious masters (For full pay and Labouchere's observations, see Schnell, 1954 [1999 reprint], pp112-6; for the colonists' view, see Boyden [ed], 2001, p 145). His knuckles were rapped by Labouchere b in September and, on 4 February 1858, Panmure decided that full pay must end on 31 March and sent Jackson, through the Governor's hands, a memorandum confirming this decision. By the time these communications arrived at the Cape there had been a change of government, Palmerston having resigned, and in Derby's new administration MajorGeneral Jonathan Peel, Sir Robert Peel's brother, replaced Panmure as Minister for War. Peel felt that he had no discretion to change his predecessor's decision, and insisted that it be carried out (Schnell, 1954 [1999 reprint], p 115-6).

Crisis in India

While this was going on, the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny at Meerut in May 1857, and the need to rush reinforcements to the scattered and hard pressed garrisons, created a new crisis for the British government and the military. Grey found himself torn between the demands of his superiors in London for the release of troops for India and the expectations of the colonists that he provide the means to preserve them from the depredations of what they, and the British press, called the 'Caffres'. The pressures upon him could clearly be seen in an exchange of dispatches between London and Cape Town that appeared in the press in April 1858 (The Times, 17 April 1858, p 10). In one, dated 5 February, Labouchere assured Grey, in silky diplomatic language, that he was reluctant to urge him to weaken the defences of the Colony beyond what was in his [Grey's] judgement indispensable, while at the same time urging upon him the pressing need for reinforcements for India, reminding him of the blinding truth that the Cape, being nearer to India, could supply reinforcements sooner.

In July 1858, Grey received a request from Bombay for more troops and, as tension in Kaffraria had eased, felt able to respond positively. The September monthly summary of the Cape Town Mail recalled that when the mutiny broke out, the whole of Kaffraria was in turmoil. News of the mutiny had, the Mail asserted, been disseminated widely in the interior to promote 'a general combination against British power'. The threat was theatrically described by one commentator: 'They have guns and horses in pretty good condition, are excellent shots, and possess ... the material for the finest light infantry in the World.' (The Times, 25 May 1857, p 8). A sudden reduction in the forces available to Grey would, the Mail said, have had dire consequences, but now that conditions had improved strong reinforcements were assembling (Cape Town Mail, monthly summary, 20 September, reported by The Times, 30 October 1858, p 10). On 4 September, Grey wrote to Lord Elphinstone, the Governor at Bombay, to say that he was sending him a total of 2 931 officers and men, including volunteers from the GMS (British Library, Oriental & India Office Collections [OIOC], UPS/5/523, p101). Despite a lack of information about longer term prospects (OIOC, UPS/5/523, p 105, setting out terms described as 'liberal' by The Bombay Standard, 3 January 1859, p 15), many Germans volunteered, and 1 068 officers and men travelled to India with Wooldridge, Ensign Simner being one of them. For all their shortcomings as settlers, reports of their conduct before and during the voyage were good, praising their drill and discipline.

Those who stayed behind

About a thousand officers and men remained at the Cape. Throughout 1859 and 1860, their numbers declined steadily - by the end of 1859, a total of 102 legionaries had died, 96 of dysentery and other diseases, five by suicide, and one, Captain Heinrich Ohlsen (after whom the settlement at Ohlsen, near Stutterheim, was named), was murdered near Fort Murray in February 1857, receiving assegai and axe wounds. By March 1861, all the remaining Settlers had been paid off (Schnell, 1954 [1999]. p 145). What might have seemed at the outset, in London, to be a fairly straightforward operation proved in practice to be a challenging task for Grey and his advisers, who had to solve the conundrum of

keeping the men contentedly at work despite their dual role as settlers and soldiers. The GMS were expected to clear land, plant crops, build houses and behave generally as ordinary settlers, while at the same time providing an effective military response to any threat of disturbance in Kaffraria. Not surprisingly, affairs did not go strictly to plan. A settler's life was uncongenial to the more adventurous spirits; progress in house building and cultivation was slow; the wilder elements committed crimes large and small; and inevitably there were desertions (Schnell, 1954 [1999 reprint], pp 134-8, 268).

In the longer term, many former members of the GMS gave valuable service to South Africa, as can be seen in a section entitled 'The Contribution of the British German Legion to South Africa' in Germans in Kaffraria. To that list can be added Major Charles Mills (later Sir Charles Mills), brigade major of the BGL, and Military Secretary for the GMS. Mills was born at Ischl in Austria-Hungary, and was educated chiefly at Bonn. He served in the ranks with the 98th Regiment in China and India, and was wounded in Gough's Pyrrhic victory against the Sikhs at Chillianwallah in 1849 (medal). In 1851, he was commissioned as an ensign in the 98th, serving for a period as adjutant. He was promoted to lieutenant in the 50th Foot in 1854, but in August 1855 joined the 3rd Light Infantry of the BGL with the rank of captain, becoming brigade major of the 1st Brigade and travelling with them to Constantinople. At the Cape, he succeeded Major Follenius as Military Secretary, and in due course received a grant of land in Stutterheim. He served for a period as Sheriff of King William's Town and as Secretary to the Government of Kaffraria. In 1866 he was elected to represent King William's Town in the Cape Parliament, but in the following year entered the colonial service, later becoming permanent under-secretary in the colonial secretary's office. He was Agent-General for the Cape Colony in London from 1882 until his death there in 1895, and was made KCMG in 1885 (Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement v 3,1901, p 175).

Notes

a. At least one member of the BGL saw action in the Crimea. Captain William Gordon Cameron, Grenadier Guards, was serving with his regiment before Sebastopol when, on 18 October 1854, he was severely wounded. Despite his injuries, he was later given command of the 3rd Light Infantry BGL and, in January 1856, led his regiment to Scutari. One of his qualifications may have been his attendance, early in life, at the Military College in Dresden. He went on to a distinguished military career, becoming a full general and, between 1890 and 1894, he commanded the British forces in South Africa. [Army List, Rodowicz, and WO 43/970).

b. In 1859, Grey's independence would again draw the ire of his masters in London, and his recall would follow. In some of his public utterances, he had referred positively to the possibility of a federation in southern Africa, believing that HM's Govemment would look favourably upon such a development. He was mistaken, the Colonial Office took umbrage, and in June he was recalled. This was not well received at the Cape, and as he left Government House the horses were taken from his carriage and it was drawn by a crowd to the dockside. A petition of 2000 signatures, praying for his restoration, was sent to the Queen. By the time that Grey arrived in Britain, Derby's ministry had fallen and the new Colonial Secretary, Newcastle, reinstated him, although he adjured him to say no more about federation.

Bibliography

OIOC - British Library, Oriental & India Office Collections.

PRO - Public Records Office, Kew, nowthe National Archives (UK).

SFO - Simner Family Papers, now in the custody of Mrs Wendy Roderick and referred to with her consent.

Act No 5, 1857, Cape of Good Hope, 29 June 1857.

King William's Town Gazette, 15 January 1859.

The Times, various dates.

Boyden, P B (ed), The British Army in Cape Colony: Soldiers' Letters and Diaries, 1806-58 (Society for Army Historical Research Special Publication No 15, 2001).

Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement v 3, 1901.

Douglas, G & Ramsay, G D (ed), The Panmure Papers (2 vols, London, 1908).

Schnell, E L G, For Men Must Work, (Cape Town, 1954, re-printed 1999).

Schwar, J F & Pape, B E, Germans in Kaffraria 1858-1958, (King William's Town, 1958).

Victor, S, Curator of the Amathole Museum, King William's Town, personal correspondence.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org