The South African

The South African

James Jacobs is currently the Resident Military Historian at the South African Army College. In this capacity he lectures in military history to different courses in the SANDF, such as the Army Officers' Formative Courses, Junior Command and Staff Courses and the Senior Command and Staff Programme at the South African National War College. He joined the SADF in 1973 and served as an armour officer at 1 Special Service Battalion in Bloemfontein. During the period 1977 to 1980, he served in various appointments in the operational areas of SWA and on the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia border. In 1983, he became a lecturer in military history at the Military Academy, Saldanha, and in 1989 became the head of the Department of Military History. He also served at the SANDF Documentation Services (Archives). His academic qualifications include the B Mil, University of Stellenbosch, 1976; BA Hons, Strategic Studies, UN/SA, 1981; Hons B Mil, Military History, University of Stellenbosch, 1984; MA, Cum Laude, History, University of Stellenbosch, 1988; and PHD, History, University of the Orange Free State, 1994. He is currently writing two books that will be completed in 2005. He is married to Sanet and they have two daughters, Tania (20) and Mari (18).

Background

The Union of South Africa entered the Second World War on 6 September 1939. Prime Minister J C Smuts believed that the Union Defence Forces (UDF) had to make a major contribution in the Middle East, deemed to be the most important theatre of operations for the British Empire. The reason for this was that without the oil of the Persian Gulf and the use of the Suez Canal, its war effort would be crippled (Hancock, 1968, pp 366-7).

South African participation in the North African campaign is associated with names such as Sidi Rezegh, Taib el Essem, Tobruk and El Alamein. When South African ex-servicemen annually commemorate the last named event, they refer to the battle conducted during October and November 1942. This was the victory of the British Eighth Army under command of General Bernard Montgomery. What is less well known is that South African forces played a more important role in the so-called First Battle of El Alamein, 1-30 July 1942, a battle that could have cost the British Empire the war in North Africa. Thus, the South African participation in the campaign is also not generally seen in proper perspective.

Before Alamein, it seems as if the British commanders in the Western Desert would never find a way to defeat the Desert Fox, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. However, during this battle, the British commander in the Middle East and of the Eighth Army, General C J E Auchinleck, succeeded in stopping the advance of Rommel's forces and laid the foundation for his later defeat.

General Claude Auchinleck

(Photo: by courtesy,

SANDF Documentation Centre)

The aim of this study is to analyse the role of the South Africans during the First Battle of El Alamein with specific reference to the 1st South African Infantry Division. The activities of this division will be examined within the context of the battle design of the British Eighth Army, with specific focus on 30th Corps, under whose command the South Africans resorted.

The opposing forces and the terrain

The British forces in the Middle East had to defend on two fronts. The Northern Front consisted of Palestine, Trans Jordan, Syria, Iraq and Iran. In the Western Desert, the war encompassed Egypt and Italian Libya. The Northern Front would only be threatened by the Axis powers if their forces in the Soviet Union could break through in the Caucusus region and advance south. However, the biggest threat to the security of the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf oilfields were the Axis forces operating from Libya under the command of Rommel (Calvocoressi and Wint, 1973, pp 397-8).

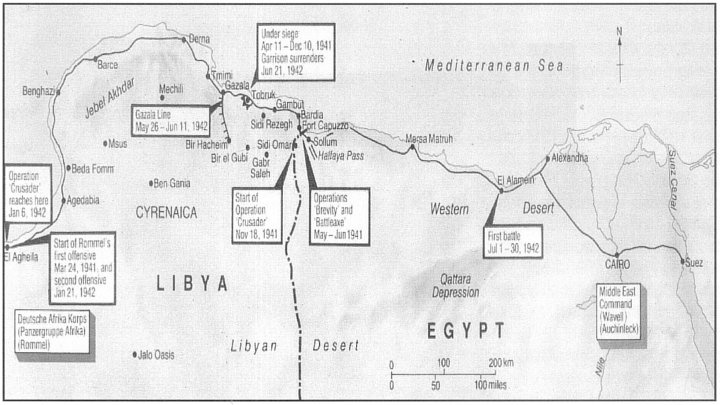

From a British perspective, the situation in North Africa did not look good by July 1942. The Eighth Army evacuated the Gazala line west of Tobruk on 14 June and on 21 June disaster struck when the garrison of Tobruk surrendered and 33 000 men, mostly South Africans of the 2nd South African Division, went into captivity. Initially, the Eighth Army tried to defend Egypt in the vicinity of Mersa Matruh, but this town could easily be enveloped from the south. Thus, Auchinleck decided rather to withdraw to El Alamein, confirming a decision by the British General Staff that this would be the best position from which to defend Alexandria, Cairo and the Suez Canal (Auchinleck, January, 1948, p 328).

The so-called El Alamein Line was the last obstacle between Rommel and the Suez Canal. In contrast to the image of an impenetrable defensive line of fortifications, minefields and barbed wires, portrayed by the BBC and the British papers, it was not much more than a line on a map (Barnett, 1983, p 195). In addition, for weeks, the Eighth Army had only known defeat at the hands of Rommel (Dorman O'Gowan, 1967, p 1 068).

Map showing the Axis advance to El Alamein, 22-28 June 1942

(Source: M Wright (ed), The World at Arms, Reader's Digest Illustrated History of World War II, p 90).

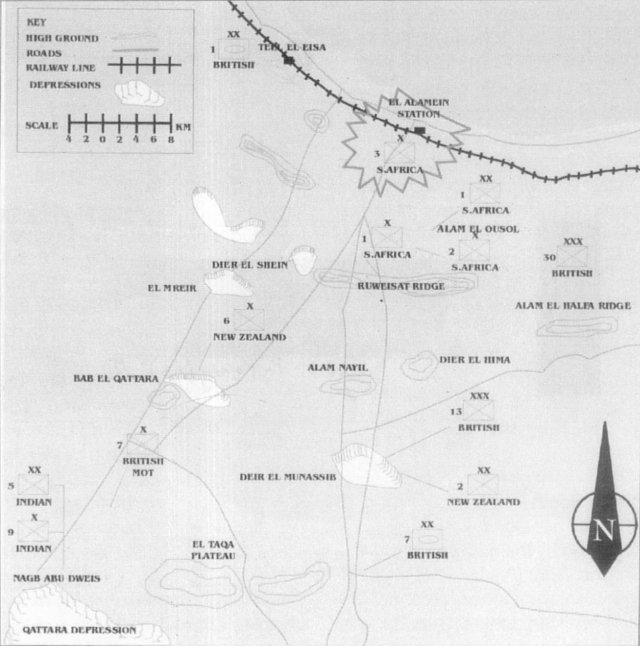

The defensive position was divided into three corps areas with 30th Corps near the coast and 13th Corps in the south. In the Nile Delta, 10 Corps was deployed in depth. In the north, near the small railway siding of El Alamein, a defensive position had been prepared in 1941 by the 2nd South African Division, but by now it was in a dilapidated state. It was from here to the northern slope of the Ruweisat Ridge that the 1st South African Division would be deployed by the end of June 1942 (Agar-Hamilton and Turner, 1952, p 271).

The 18th Indian Brigade was deployed on the western part of the ridge, at Deir el Shein. They had just arrived from Iraq and were placed in hastily prepared defensive positions. They had to cover a gap of twelve kilometres between the left flank of the South Africans and the right flank of 13th Corps. The 1st British Armoured Division was earmarked to deploy east of this position on the Ruweisat Ridge, but was still on its way from Mersa Matruh by 30 June. The tactical headquarters of the Eighth Army was situated to the east of this position on the Alam el Haifa Ridge (Dorman O'Gowan, 1967, p 1 062).

The British 13th Corps had to defend the area from the southern slope of the Ruweisat Ridge up to the Quattara Depression with weakened infantry while, by 30 June, the 7th British Armoured Division was also still on its way from Mersa Matruh. The Quattara Depression, more or less 60km south-west of El Alamein, constitutes an area of 200km2 and consists mostly of salt lakes and soft sand so that even camels carrying a load could not navigate it. (Essame, 1976, p 36). South of this lay the Sahara Desert, also impassable for motor vehicles (Barucha, 1956, p 417). Thus the position could not be enveloped from the south.

Rommel's only chance of defeating the Eighth Army and capturing Alexandria and Cairo was to break through this thin defensive line and to destroy the British Armoured formations before they could recuperate. On the surface, it looked as if this would be easy to achieve. However, Rommel's forces had also been weakened by the continuous fighting since the start of the offensive at Gazala on 26 May. He had only 55 German tanks, 2 000 infantry and some artillery, supplemented by thirty obsolete Italian tanks, 5 500 infantry and 200 guns (War Diary DAK, 30 June 1942; Dorman O'Gowan, 1967, p 1 070). His biggest problem, however, was to keep this meagre force supplied along a long line of communication. Tobruk harbour could only handle a limited quantity of Rommel's supply needs and the only other two suitable harbours, Tripoli and Benghazi, were respectively 2 080km and 1 280km from the front at El Alamein. This situation was aggravated by the weak road and limited railway system along the coast. Also, from Tobruk eastward the Axis supply columns were within striking distance of the Royal and South African Air Forces deployed in the Nile Delta (Van Creveld, 1977, pp 194-7). Thus, everything depended on whether Rommel's forces could break through the El Alamein line and manoeuvre into a good position in the open terrain from there to the Nile Delta in order to destroy the British armoured formations before they were able to recuperate (Macksey, 1968, p 94).

Map showing British Eighth Army positions on 30 June 1942.

(Source: P Young (ed), Atlas of the Second World War, p 47).

Auchinleck realised this and he restructured the control of firepower in the Eighth Army. At this stage, the British had more 6-pounder anti-tank guns available, the control of field artillery fire was more centralised and more extensive use of land mines could be made. Auchinleck realised that it was crucial to slow down the tempo of operations to win time and to allow the Eighth Army to build up strength for a counter-offensive (Playfair, 1960, p 333).

Still, the absence of British armour on 1 July was critical. Furthermore, although the British had 150 tanks left, most were no match for the German panzers and anti-tank gunners. Only twenty Grant medium tanks could match the German forces in a armoured showdown (Barnett, 1983, pp 189-99). Also, by 1 July, the Australian 9th Infantry Division had not yet reached the Nile Delta from Syria.

However, Rommel's situation was aggravated by the loss of reliable information about the Eighth Army. Before this stage of the campaign, a reliable source had existed in Cairo. Early in the war, Italian crypto-analysts had broken the code used by the American military attache in Cairo, Colonel Bonner Fellers. By radio, Fellers had submitted the order of battle of the Eighth Army to Washington on a daily basis, but in June 1942, the British had discovered this and, on 29 June, changed the code. Thus, on the eve of the battle, Rommel had little information regarding the strength and deployment of the Eighth Army.

During the battle, another blow would cripple the Axis. The Wireless Intercept Section under the command of Lieutenant Seebohm was wiped out on 10 July during an Australian counter-attack (Handel, 1990, p 286).

Consequently, without realising it, Rommel let an opportunity slip through his fingers. His tank forces had already arrived in the vicinity of El Alamein by 30 June, but he had too little information on the British forces and, believing the propaganda of the BBC on the strength of the El Alamein line, he decided to attack early on the following day (Liddell Hart, 1974, p 239).

The 1st SA Division

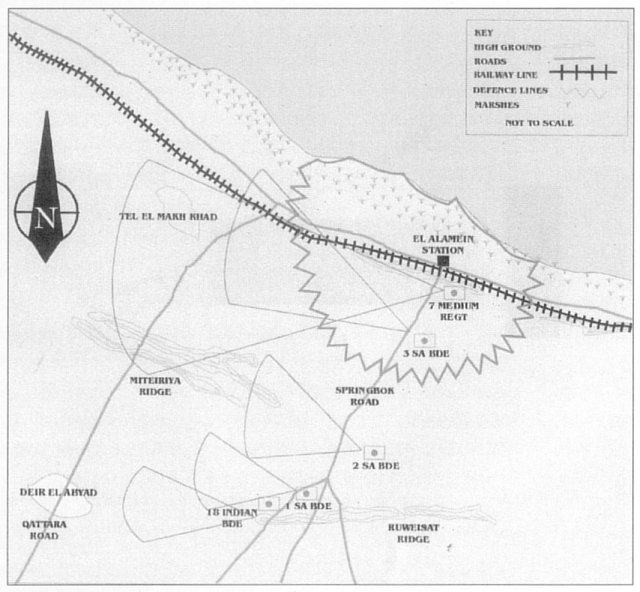

This division, under the command of Major General D H (Dan) Pienaar, had participated in the fighting at Gazala and Mersa Matruh and was deployed in the vicinity of El Alamein on 25 June 1942. In line with Auchinleck's battle design to use infantry in a more mobile role, only the 3rd Brigade was deployed inside the El Alamein Box, while the 2nd and 1st Brigades were deployed in a southerly direction towards the Ruweisat Ridge. The concept was that these two brigades would serve as the mobile component supporting the 3rd Brigade and the 18th Indian Brigade (Divisional Documents, 68, File 64: Operational Report, 1st SA Division, El Alamein Defensive Battle, 29 June - 30 September 1942, p 2).

Lt Col C W M Norrie, corps commander, seen here with the commander

of the 1st South African Division at El Alamein, Maj Gen D H Pienaar.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANDF Documentation Centre).

The division was but a third of its normal strength as detachments to the 2nd Division had been lost in Tobruk and casualties suffered at Mersa Matruh had weakened its position. Thus, in total, the division had only between 3 000 and 4 000 men available. The South African field artillery also had only sixty 25-pounder guns available for the coming battle (Divisional Documents 88, File 1 Div 81/A2, Strengths; June-October 1942). However, their fire-power was augmented by the detachment of 28 medium guns of the 7th British Medium Artillery Regiment for deployment in the El Alamein Box (Bidwell and Graham, 1982, p 239).

Rommel's first effort to break through

Early on 1 July, the German 90th Light Division tried to break through the line between the El Alamein Box and Ruweisat Ridge in an effort to reach the coast east of the South African position. At the same time, the Afrika Korps (21st and 15th Panzer Divisions) advanced south of the 90th Light with the aim of reaching a position east of the British 13th Corps. The rest of the Axis forces conducted fixing attacks against the rest of the Eighth Army. If a hole could be punched in the defensive line and if the El Alamein Box could be captured from the east, the whole Eighth Army position could be rolled up from north to south by defeating the British formations in detail (WD 403, File 34374/3: Report, Panzerarmee Afrika - Commander Southern Front, 1 July 1942).

Initially, a sandstorm aided the 90th Light Division in getting quite close to the El Alamein Box without being detected. However, as soon as the forces made contact, the South Africans beat off several attacks with ease. Thus, the attackers had to withdraw westward to regroup and to try to find another way further to the south. By this time, the sandstorm had cleared, making it easy for the South African and British artillery observers to direct fire onto them (WD 358, File A7/ME 52: War Diary, 3rd SA Brigade HQ, 1 July 1942). No South Africans were killed on 1 July (Div Docs 105, File 1 SAD/A2/2: Battle Casualties, June-July 1942).

The task facing the South Africans was made much easier by events to the south-west of their positions. Unintentionally, the Afrika Korps made contact with the 18th Indian Brigade at Deir el Shein. Although this brigade ceased to exist as a fighting entity as a result of the action that followed, the Germans also suffered losses. By the end of the day, Rommel had only 37 serviceable German tanks at his disposal and could not attack the South African position (UWH, 3224, UWH Draft Narratives: Radio message, 21st Panzer Division - Deutsches Afrika Korps, 05.40, 2 July 1942; Playfair, 1960, p 341). During the afternoon of 1 July, the 1st British Armoured Division arrived at Ruweisat Ridge, thus diminishing Rommel's best chance to break through the El Alamein line (Playfair, 1960, pp 339-41 ).

Rommel's Plan, 30 June 1942.

(Source: P Young (ed) Atlas of the Second World War, p 47).

These events would also have a negative effect on relations between South African and British commanders. The perception already existed that the latter had an irresponsible attitude towards human losses. The 18th Indian Brigade was deployed outside the artillery range of other formations of the Eighth Army. Requests by Pienaar that the brigade be placed under his command and deployed closer to the South African formations had been turned down. Pienaar was determined that the same fate would not befall his own men (Hartshorne, Cape Town, pp 157-8; C L de W du Toit: Herinneringe, III, p 5).

By last light on 1 July, Rommel's forces had not progressed further east than Deir el Shein and the Eighth Army was still in control of the situation (Playfair, 1960, p 341). Thus, in retrospect, the South Africans had thwarted the key component of Rommel's plan. By holding on to the El Alamein Box, the pivot of the El Alamein line was kept intact at a critical stage when the British armour was still on its way from Mersa Matruh to El Alamein. Hence the El Alamein Box would become a thorn in the side of Rommel as the South Africans constantly harassed them with patrols and artillery fire until the end of the battle (Agar-Hamilton and Turner, 1952, p 271).

Rommel's second onslaught against the El Alamein line, 2-3 July 1942

The danger to the Eighth Army had not diminished completely. Rommel threw everything at the Eighth Army during the next two days. The main fighting occurred in the vicinity of the Ruweisat Ridge, involving the 1st British Armoured Division, but the South Africans did not escape unscathed. On 2 July, the 1st South African Brigade was in the brunt of the fighting, being hit by the left wing of attacks by the German panzers. Three officers and fourteen other ranks were wounded, including the brigade commander, Brigadier J P A Furstenburg (Div Docs. 105, File 1 SAD/A2/2, Battle Casualties, 2 July 1942). Also, the guns of the 7th Field Regiment were damaged to the extent that, by last light, they could not participate further in the battle (WD 403, File A15/ME 63: War Diary, 1st Field Regiment, SA Artillery, 2 July 1942).

The 'Desert Fox', Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

(Source: SANDF Documentation Centre).

The sacrifices were worth it, as Rommel's forces were again prevented from enveloping the El Alamein Box. However, Pienaar did not want the 1st South African Rommel forced to defend his Brigade to suffer the same fate as positions the 18th Indian Brigade. Also, if they could not hold on to their positions, the rest of the division would be enveloped from the south. His fears proved to be well founded as, by late afternoon on 2 July, it had become clear that the position could no longer be held. Without the support of artillery, the brigade would not be able to withstand another day's attacks. Also, the promised British column that was supposed to strengthen their position did not arrive! German artillery fire was very accurate and the possibility existed that the panzers could swing the axis of their advance to a more north-westerly direction and destroy the brigade, which had a severe shortage of anti-tank guns. At the same time, the 1st British Armoured Division tried to envelope the Germans, causing a gap between them and the 1st South African Brigade which made the brigade's southern flank even more vulnerable (WD 347, File A3/ME 37: War Diary, 1st SA Division HQ, 2 July 1942).

Pienaar decided that the only solution was to move the brigade to a safer position further east. This led to a serious clash with the corps commander, Lieutenant General C W M Norrie. Eventually Auchinleck was drawn into the argument during the night of 2/3 July and Pienaar got his way (Playfair, 1960, p 343). Pienaar's concern for his men was proved correct the next day, when a column of the British 50th Division (Accol) was driven out of the same position by a German attack with heavy losses, just as he had predicted (Hartshorne, Cape Town, p 158).

Rommel forced to defend his positions

By 4 July, it was clear that it was going to take a major Axis effort to break through the El Alamein line. Losses and exhaustion amongst his German forces forced Rommel to deploy more Italian troops in the front line. Auchinleck reciprocated by focussing his attacks on these Italian units, knowing that they were not of the same calibre as their allies. From 4 until 7 July, the Eighth Army conducted limited counter-attacks against Italian deployments and the South Africans had to despatch several patrols to determine their exact positions (WD 347, File A3/ME 37: War Diary, 1st SA Division HQ, 2 July 1942).

However, the Axis forces were far from beaten and Auchinleck decided to transfer the 9th Australian Division from the Nile Delta to capture Tell el Eisa to put Rommel's forces under more pressure. From this low lying hill west of the El Alamein Box, the Australians could threaten Rommel's line of communications along the coast. On the other side, Rommel concentrated his German formations to break through at Bab el Quattara. However, Auchinleck's attack pre-empted this action, forcing Rommel to rush his German forces to the north, where they launched several counterattacks against the Australians, preventing them from cutting his lines of communication, but failing to dislodge them from Tell el Eisa (Playfair, 1960, p 341). From their position in the El Alamein Box and to the south of it the South Africans provided constant artillery support to the Australians. During the main attack on 10 July the South African occupation of Tell el Makh Khad protected the southern flank of the Australians and retarded Rommel's efforts during the next two days to dislodge them from Tell el Eisa.(Playfair, 1960, p 341).

On 5 July, Lieutenant-General W H C Ramsden replaced Norrie as the corps commander and the 79th British Anti-Tank Regiment was detached to the South Africans (WD 347, File A3/ME 37: War Diary, 1st SA Division HQ, 5 July 1942). This appointment spelled disaster for relations with the corps headquarters. Pienaar and Ramsden had already been at loggerheads at Gazala in May because of Ramsden's callousness regarding human losses (Hartshorne, Cape Town, p 162).

British artillery fire plan, Northern Sector. (Source: S Bidwell, Gunners at War.)

On 11 July, Ramsden visited the divisional headquarters. He hinted that the South Africans had played far too passive a role in the battle and should be more directly involved in supporting the Australians. He wanted at least a South African brigade to attack the Miteirya Ridge to the south. Pienaar replied that, without armoured support, this would be suicide, but, against his better judgement, eventually gave in to the suggestion that a South African column of the 2nd Brigade, supported by seventeen British tanks, occupy part of the ridge with the aim of conducting raids to the south of it.

The operation was a fiasco. Too little time to prepare, movement over unknown terrain, and insufficient reconnaissance, doomed it from the start. Before the column had advanced one kilometre, three British tanks had become stuck in a minefield and were hit by anti-tank fire, while others experienced mechanical problems. The tanks advanced too early and could not be supported by the South African artillery. Luckily, Ramsden realised his mistake and withdrew the force. Apart from the damage to the British tanks, no losses were suffered (C L de W du Toit: Herinneringe, III, pp 8-9).

The German attack against the El Alamein Box, 13 July 1942

Rommel's attack on 13 July was a desperate effort to cut off the Australians from the main El Alamein positions and to disrupt the British defence system. The 21st Panzer Division was instructed to attack the El Alamein Box from a south-westerly position, supported by the 2nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment 104.

In the Box, the Royal Durban Light Infantry bore the brunt of the fighting. They did not have adequate anti-tank guns and the accuracy of the German artillery support cut the telephone cables of the South Africans, making field artillery support difficult. For most of the day, the South Africans beat back the attacks, but by 16.10, German tanks, supported by dive bombers, advanced up to 300m from the South African positions. The field artillery of the 9th Australian Division, as well as the 7th British Medium Regiment in the Box, had to help halt the German advance (WD 347, File A3/ME 37: War Diary, 1st SA Division HQ, 2 July 1942). By last light, the 79th British Anti-Tank Regiment was also deployed near the threatened point but, by that time, the German attack had lost its momentum (Tungay, Cape Town, pp 252-3).

South African losses on this day entailed nine dead and 42 wounded (Roll of Honour, 19391945; Div Docs 105, File 1 SAD/A2/ 2: Battle Casualties, 13 July 1942). Compared to similar events during the war, this was not high, but the significance of their ability to withstand the panzer onslaught outweighed this. The loss of the El Alamein Box would have ruptured the El Alamein line, cut off the Australians from the rest of the Eighth Army and probably forced a general retreat to the Nile Delta.

Auchinleck regains the initiative

The Axis attacks from 11 to 13 July exhausted Rommel's forces. Thus, Auchinleck decided to change over to an offensive posture. Apart from the situation of the Axis forces, British reinforcements arrived at a steady pace and the British war cabinet assured Auchinleck that it would be a long time before the German forces in Russia would be able to reach the Middle East through the Caucasus. Thus, he could use forces from Iraq and Persia to enable the Eighth Army to conduct offensive operations.

However, during the second half of July, Rommel proved not only to be a good commander during offensive operations, but also in defence. Thus, Auchinleck's efforts were frustrated. However, the effort was not wasted as the Eighth Army gained valuable experience in German defensive tactics. Rommel's extensive use of minefields, covered by infantry and small, mobile armoured forces, enabled him to thwart the British efforts that lacked proper coordination and cooperation between infantry, armour and artillery. Based on this experience, Montgomery, Auchinleck's replacement as commander of the Eighth Army, could later find suitable solutions to defeat Rommel at El Alamein (Dorman O'Gowan, 1967, pp 1 072-5).

Apart from this, the British commanders were too inflexible to adapt their tactics at critical junctions in the battle. Thus, Rommel's forces found time to recuperate and retain their positions, with heavy British losses. Before July 1942, British commanders repeatedly launched tank attacks, insufficiently supported by artillery and infantry, into Rommel's defensive positions, making them easy prey to crack German and Italian anti-tank gunners. During this battle, they were extremely hesitant to use their tanks once a weak point had been discovered in the Axis defensive positions. The El Alamein Box still constituted an important component of the British defensive line, but the operations from 14 to 23 July were conducted mainly in the vicinity of Ruweisat Ridge. (Playfair, 1960, pp 347-57). During these attacks, the South Africans played mainly a supportive role. The South Africans were more directly involved in the last operation of the battle, Operation 'Manhood'. The division was tasked to breach the first of two minefields of the Axis between the Miteiriya and Ruweisat ridges. The 69th British Infantry Brigade then had to move through the breach and breach the second minefield so that the British armour could exploit the breakthrough (WD 347, File A3/ME37: War Diary 1 SA Division HQ, Appendix, 30th Corps Operational Order No 68 of 26 July 1942, pp 1-2).

However, the operation failed mainly because the British armour could not move fast enough through the breaches in the minefields. When they eventually did, the element of surprise was lost and they were, as in the past, driven back by German anti-tank fire. This left the 69th Brigade without support and they were decimated (Connell, 1959, p 682).

Another problem was that the British' armour had not been ordered to advance through the minefields at a specific time and it was left to the discretion of their commander to decide when to do so. Realising what was at stake, Pienaar urged him to move his tanks, but both the tank commander and Ramsden wasted even more time because they wanted to personally inspect the breaches, mistrusting Pienaar. The result was that the tanks did not advance before first light, as was the intention, but only at 11.00, straight into killing zone of the waiting German anti-tank gunners (UWH Narratives and Reports, Middle East, Vol II, 1st SA Division, Tobruk to El Alamein, p 1, Interview with Colonel H F C Cilliers on 26 April 1949).

The destruction of the 69th British Brigade ought also to be blamed on the British generals. Apart from wasting valuable time, their planning also left much to be desired. Ramsden sent the infantry into unknown territory, without studying air photographs of the terrain that were available to him (C L de W du Toit: Herinneringe, III, p 10).

The Eighth Army on the defensive, 28 July 1942

By 28 July, Auchinleck decided that he would have to postpone the intended destruction of Panzerarmee Afrika. British losses were already high, while Rommel had by then received some reinforcements (Liddell Hart, 1974, p 300). At the same time, British reinforcements were arriving at such a slow rate that a large-scale offensive before September was out of the question. Therefore, the army headquarters issued instructions to the corps commanders to prepare to defend their positions, bringing the 1st Battle of El Alamein to an end (Playfair, 1960, p 359).

Conclusion

During July 1942, 12 700 officers and men of the Eighth Army were reported killed, wounded or missing in action (Auchinleck, January, 1948, p 330). Total South African losses, from 26 June to 30 July 1942, were 433 officers and other ranks of whom 164 were killed, 253 wounded, and eight taken prisoner of war, while eight received treatment for shell shock (Roll of Honour, World War 11,1939-1945; Div Docs 105, File1 SAD/A2/2: Battle Casualties, 1-30 July 1942). Thus, compared to the rest of the Eighth Army, the South African losses were relatively light. The reasons for this were that, only on 13 July did the German panzers attack them specifically, and Pienaar did everything in his power to prevent a repetition of Tobruk and Deir el Shein. Furthermore, concentrated artillery fire improved the fire power of the defending British forces, while making the attackers' task more difficult.

Owing to several reasons, conflict between British and South African officers was inevitable. South African commanders were extremely sensitive about high casualty rates, knowing that the population of the Union was small and the country was divided on the issue of participation in the war on the British side. Furthermore, the surrender at Tobruk had been a painful experience that nobody wanted to repeat. British officers did not always understand this.

It is clear that the South African division played a decisive role during the battle, but this must be seen in perspective. The division executed a very important function on 1 July, but their losses would have been higher without the action of the brave men of the 18th Indian Brigade at Deir el Shein. Without the help of the 1st British Armoured Division on Ruweisat Ridge and the British and Australian artillery, the South Africans would not, on their own, have been able to withstand the onslaught of the panzers on 13 July. After the capture of the Tell el Eisa hill by the Australians on 10 July, the South Africans only played an active role on 13 July and again in Operation 'Manhood'.

The importance of the South African contribution was that it was part of a team effort. Their contribution prevented Rommel's forces from capturing Alexandria, the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf oilfields. This was of vital importance to the Allied war effort, as it enabled the British forces, in cooperation with their American allies, to drive the Axis forces from North Africa.

SOURCES

Agar-Hamilton, J A I, and Turner, L C F, Crisis in the Desert, May-July 1942 (London, 1952).

Barnett, C, The Desert Generals (London, Pan, 1983).

Bidwell, S and Graham, D, Fire Power. British Army Weapons and Theories of War, 1904-1945 (London, 1982).

Bidwell, S, Gunners at War. A Tactical study of the Royal Artillery in the Twentieth Century (London, 1970).

Butler, J R M (ed), History of the Second World War, UK Military Series (Playfair, ISO (et al), The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume III, September 1941-September 1942. British fortunes reach their lowest ebb (London, 1960)).

Colvocoressi, P and Wint, G, Total War. Volume I, The War in the West (New York, Ballantine Books, 1973).

Connell, J, Auchinleck. A Biography of Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck (London, 1959).

Foss, C F, Artillery of the World (London, 1974).

Hancock, W K, Smuts, Volume II, The Fields of Force, 1919-1950 (Cambridge, 1968).

Handel, M I (ed), Intelligence and Military Operations (London, 1990).

Hartshorne, E P, Avenge Tobruk (Cape Town, 1960).

Howard, M, The Mediterranean Strategy in the Second World War (London, 1966).

Kruger, D W, The Making of a Nation. A History of the Union of South Africa, 1910-1961 (Pretoria, 1971).

Liddell Hart, B H, History of the Second World War (London, Pan, 1974).

Macksey, K, Afrika Korps (London, MacDonald, 1968).

Prasad, B (ed), Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War, 1939-1945. Campaigns in the Western Theatre (Bharucha, P C, The North African Campaign, 1940-1943 (London and Culcutta, 1956)).

Richards, D and H St George Saunders, Royal Air Force, 1939-1945, Volume II. The Fight Avails (London, 1954) .

Sloan, C E E, Mine Warfare on Land (London, 1986).

Tungay, R W, The Fighting Third (Cape Town, 1947).

Van Creveld, M, Supplying War. Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton (London, 1977).

Young, D, Rommel (Glasgow, 1975).

Young, P, Atlas of the Second World War (New York, 1974).

Published articles:

Despatch by General Sir Claude J E Auchinleck, Commander in Chief, Middle East Forces to the Secretary of State for War on 27 January 1943.

Operations in the Middle East from 1 November 1941 to 15 August 1942. Supplement to The London Gazette, 13 January 1948.

Dorman O'Gowan, E, "1st Alamein - The battle that saved Cairo" in Purnell's History of the Second World War, 7, 3/6, 1967.

Du Toit, C L de W, 'Die Herinneringe van Generaal Christiaan Lodolph De Wet Du Toit, Deel III' in Militaria, 10/4, 1980.

Essame, H, 'First Alamein' in War Monthly, 22, January 1976.

Archival Sources: SANDF Documentation Services:

Divisional Documents (Div Docs) 68, File 64: Operational Report, 1 st SA Division, El Alamein Defensive Battle, 29 June to 30 September 1942.

Div Docs, 88, File 1 Div/81/A2: Strengths, June to October 1942.

Div Docs, 105, File 1 SAD/A22: Battle Casualties, June to July 1942.

Union War Histories (UWH) Narratives and Reports, Middle East, Vol. II, 1 st SA Division, Tobruk to El Alamein.

UWH 324, File 34374/3 Reports, Panzerarmee AfrikaCommander Southern Front, July 1942.

UWH 177, File 22926/1: War Diaries Deutches Afrika "Korps, June and July 1942.

UWH 224, Draft Narratives: Radio Message, 21st Panzer Division - Deutsches Afrika Korps, 05.40, 2 July 1942.

UWH 378, Maps.

War Diaries(WD) 343, File C28/33: War Diary 1st South African Division Administrative Headquarters.

WD 347, File A3/ME37: War Diary 1st South African Division Headquarters.

WD 358, File A6/ME 49: War Diary 1 st South African Brigade Headquarters.

WD 361, File A7/ME 52: War Diary 3rd South African Brigade Headquarters.

WD 372, File A 15/ME 63: War Diary 1 st Field Regiment South African Artillery.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org