The South African

The South African

by Emrys Wynn Jones

At the outbreak of the Crimean War in March 1854, the British army was below strength and experiencing difficulty in recruiting. Those who did enlist could not be turned into effective soldiers without a considerable period of training. The Aberdeen ministry decided, therefore, to raise a foreign legion of men accustomed to discipline and trained in arms. In December 1854, a Foreign Enlistment Bill was hurried through Parliament, not without vigorous, even xenophobic, opposition in both Houses, and in the country too (18& 19 Vict. c.2). Some of its opponents were concerned that a large force of mercenaries on British soil could become a threat to the state; some were appalled that Britain should hire foreigners to fight her battles; some believed that mercenaries were untrustworthy and prone to desert in the face of the enemy; and others correctly foresaw that there would be strong objections in the states from which the recruits were likely to come. Although the predicted opposition soon manifested itself in the German states, and despite the measures taken there and in Denmark to stem the flow of recruits, the presence of considerable numbers of unemployed or impoverished officers and men who had served in the Schleswig-Holstein War (1848-50), and a supply of men who had completed their military training, provided a source of volunteers. Even Friedrich Engels, a well-informed and perceptive commentator on military matters, misjudged the position, saying, with ponderous wit, that the use of flogging under the British military code would overcome any temptation to accept the high bounty and good pay (Engels, 1855, p 202). The outcome was undoubtedly a disappointment to the Government, but by no means

a total failure. At their height the Foreign Legions German, Swiss and Italian - reached a total of 15 873 men, of whom 9 071 were in the British German Legion (PRO, W06/196. Bayley, 1977, p 149, gives a slightly higher total).

Benjamin Simner in later life, as a captain of the 76th Regiment.

He was promoted to captain in April 1875 and retired in May 1877.

(Photograph reproduced by kind permission of Mrs Wendy Roderick,

Simner's great-great-granddaughter).

Although the Enlistment of Foreigners Act received the Royal Assent on 23 December 1854, its implementation was delayed by the fall of Aberdeen's ministry in January 1855. His successor, Palmerston, appointed Fox Maule Ramsay, 2nd Lord Panmure, as Secretary for War, and one of Panmure's early tasks was to oversee the recruitment and assembly of a large body of foreign legionaries in the teeth of the opposition of many German states, led by Prussia. At first his attitude was lukewarm, but the needs of the army in the Crimea, and opposition at home to other possible measures to stimulate recruitment, compelled him to act. The task called for leadership and organisation, and here he benefited from action taken by the previous administration. In December 1854, Baron Richard von Stutterheim had been invited to London to discuss the feasibility of forming a German legion (Bayley, 1977, p 67). Stutterheim was a product of the Prussian Cadet School at Cologne. In the 1830s, he had served in Spain with a British Auxiliary Legion commanded by the fire-eating Lieutenant-Colonel George de Lacy Evans (later a full general) in the cause of Queen Isabella against the Carlists. He also fought in the Schleswig-Holstein Campaign, distinguishing himself in the field, but showing less talent for staff work for which, it was said, he lacked 'neatness, conscientiousness, prudence and diligence' (French & Kinsey, 1975). Panmure now authorised Stutterheim to recruit a contingent of at least 5 000 men in Germany and, on 25 April, he was granted the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

By the end of April, Stutterheim was in Hamburg, and recruiting soon started in earnest. Barrack huts were erected on the island of Heligoland, British territory since 1814, and supplies flowed in. British agents were active in north Germany, offering the owners of coasting vessels a bounty of £2 for every man conveyed to Heligoland (The Times, 3 July 1855, p 10). The steamer, Otter, visited 'the banks of the Elbe and the coast of Hanover, Hamburg and Holstein' to embark recruits despite the efforts of the authorities to counteract the operation. Numbers grew steadily and, by 21 July, 1 500 men had arrived at Shorncliffe, near Folkestone. The Times reported that 'most of them are soldiers who have completed their training, and a good number appear by the medals on their breasts to have already smelt gunpowder.' (The Times, 21 July 1855, P 9). Later in July, press reports in Germany, repeated by The Times, disclosed the nature of Stutterheim's brief. He was to raise 10 000 men, at £10 per head, a financial venture which must surely have infuriated those who had opposed the Enlistment of Foreigners Bill on the grounds that its objectives were no better than a sordid trade in flesh and blood. The Legion was to be divided into two brigades, each of four regiments, and each regiment was to consist of ten companies of a hundred men (The Times, 23 July 1855, p 9. At its height, the BGL consisted of six regiments of light infantry, three of Jagers, and two of light dragoons).

Into this exotic and, as will be seen, increasingly dysfunctional formation came Ensign Benjamin Simner, aged seventeen and an unlikely legionary, to be swept away like a leaf on the surface of a turbulent river. He was the eldest son of Abel and Anne Simner, a Welsh couple living in London (SFP and author's personal knowledge). Abel Simner was born and brought up in Denbigh, in north Wales, but moved, at the age of seventeen, to London, where he obtained a post as a clerk in the newly established Poor Law Commission, joining in the same year (1836) as another Welshman, [Sir] Hugh Owen, who rose to be Chief Clerk of the Local Government Board (effectively its Permanent Secretary). Owen was one of the founding fathers of the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, and Abel Simner became his loyal henchman in his tireless labour to promote the College (Dictionary of Welsh Biography down to 1940, 1959, p 706. Ellis, 1972, gives a comprehensive account of Owen's part in founding the College, and in fighting its early battles). The Simners had three sons and one daughter, the first of whom was Benjamin, born in London on 22 December 1837. All three of Abel's sons attended the City of London School, Benjamin and his brother William entering on the same day in 1851, and their younger brother Abel in 1862 (SFP).

How did Benjamin Simner, with no private means, obtain a commission in the British German Legion (BGL)? The answer lies in part in the fact that his commission in the BGL was without purchase. An interview in the right quarter could open doors, and for that an influential introduction was all that was required. One who could well have arranged an introduction was Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Poor Law Commissioner from 1839 to 1847 and, in 1855, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in Palmerston's administration. He would certainly have known Hugh Owen, and probably Simner Senior too. Why Benjamin chose the BGL can only be guessed, but whatever the reason, he obtained a commission as an ensign in the 5th Light Infantry from 21 November 1855 (SFP). No time was wasted, and on 28 November Benjamin, not yet eighteen, departed via Hamburg for the depot at Heligoland.

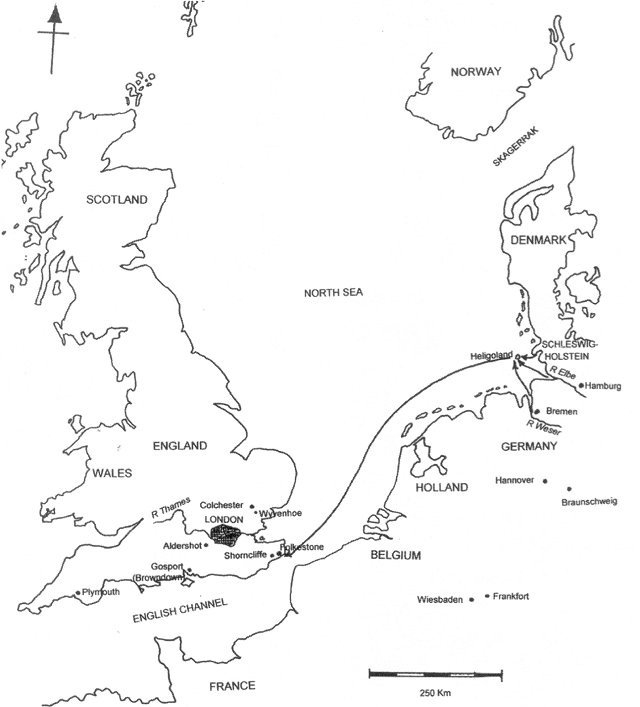

Map 1: Germany, Heligoland and Great Britain:

The recruitment and assembly of the British German Legion, 1854-5.

The difficulties of organising a foreign legion soon became apparent. Attention was quickly given to its legal status, and the military laws of England were translated into the languages spoken by the recruits, but despite the army's experience of commanding troops who knew no English, notably in India, it seems that the difficulty of transmitting commands to formed bodies of troops may not have been resolved. Early in August 1855 a visitor to Shorncliffe Camp told a disturbing tale (The Times, 6 August 1855, p 9):

'We were not prepared, however, to hear the brigadier [Wooldridge] issue his commands for the several movements - to German soldiers not understanding a word of English - in our language, the brigadier's English words of instruction being repeated in German to the battalions by the officers, who understood both languages. We cannot conceive of anything more objectionable than such a system, and we should like to hear the minute directions given in that way for a complicated manoeuvre ... 'a

This was a brigade that was said to be nearly ready for service in the Crimea, but the recent memory of the tragedy that befell the Light Brigade at Balaclava, itself said to be the result of a misunderstanding of an order, must have given pause to those who were to command it in the field as part of what was already a polyglot alliance.

Panmure now turned his attention to the task of transporting the first contingent of legionaries to the Crimea. On 4 August he informed General James Simpson, who had succeeded to the command in the Crimea after Raglan's death, that 'a fine brigade of 2 000 Germans under Brigadier-General Wooldridge leave this [country] in a fortnight', although he later added that they would sail only when they were ready (Douglas & Ramsay, 1908, p 338). They did not, in fact, depart until mid-October, preceded then by a typically gruff commendation from Panmure: 'They are fine looking men, and will do more work than your youngsters, and be more handy.' (Douglas & Ramsay, 1908, p 434). On 11 October, the 1st Jagers, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel August Schroer, nursing a broken arm, left Shorncliffe for Portsmouth to embark on the steamer, Imperatrix.

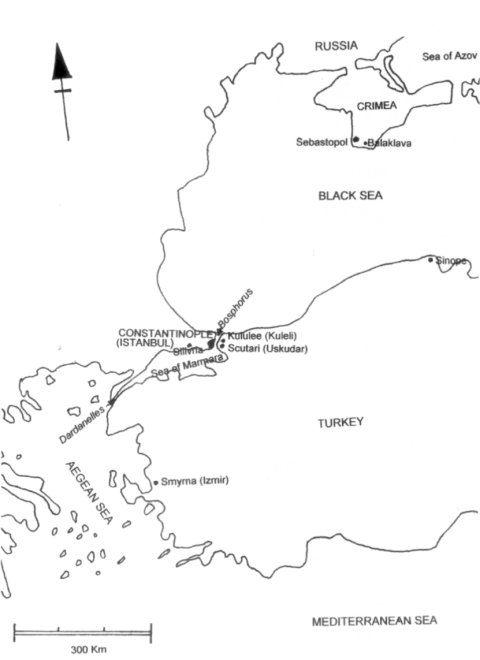

Map 2: Turkey, the Black Sea and Crimea, 1854-6, showing the dispositions

of the brigade of the British German Legion destined for the Crimea but retained

at Scutari, Kululee, Silivria and Sinope.

The Times (12 October 1855, p 10; 15 October 1855, p 10) gave a comprehensive account of the regiment, its officers, its strength and its mountain of baggage (143 tons), providing us with a rare glimpse of their uniforms, arms and accoutrements:

' ... they are all armed with the modern rifle, and their uniform resembles closely that of the British Rifle Brigade; their knapsacks are covered with cowhide, with the hair outwards, and a flap-piece shelters their great coat from the wet. Many of the men wore the Cross of Merit for service in the Schleswig-Holstein war, and King William of Prussia's medal.'

Imperatrix sailed on 13 October, and was followed on 30 October by the steam troopship, Simoom, carrying the 1st Light Infantry under its redoubtable commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Adolf von Hake. In its account of their departure, The Times (31 October 1855, p 10) told a story calculated to charm a Victorian audience:

' ... one of the privates was discovered to be a young woman, and a very fine handsome young woman too, French, the wife of a soldier of the regiment, who is Swiss. This gallant wife regularly enlisted, and passed muster, it would appear afterwards. On the discovery of her sex this fact was reported to the Colonel, who ordered her to be landed, but she begged so hard, and her appeal was so heartily and generally supported by the comrades of her husband, that she has been allowed to accompany him in her capacity as a soldier, pro tem ... '

Wooldridge accompanied neither regiment, but sailed from Dover on the packet Queen on 20 October, reaching Constantinople on 31 October aboard the Marseilles mailboat (The Times, 24 October 1855, p 12 and 12 November 1855, p 7. According to Rodowicz, he was quartered in the Sultan's rooms at the Janissary Barracks at Kulali) .

Events now intervened. Dismayed that he was to receive this brigade so late in the season, Simpson told Panmure that 'he could not hut' them, and that they would be exposed to the hardships of a Crimean winter under canvas (Douglas & Ramsay, 1908, p 463). Panmure reacted quickly, sending a telegram to Major-General Henry Storks, commanding British forces in Constantinople, upon receipt of which Storks undertook to house 3 000 Germans at Scutari. Despite this setback, Panmure was still intent on sending four regiments as far as Scutari, and the movements went ahead. The Jagers arrived early in November (The Times, 15 November 1855, p 8), and were quartered in part of the Barrack Hospital at Scutari: before the month was out many of them had succumbed to cholera (The Times, 29 November 1855, p 8). Cholera was still raging when the 1st Light Infantry arrived towards the end of November, and they were sent initially to Silivria, about 90 km west of Constantinople on the Sea of Marmara (The Times, 7 December 1855, p 8). The 3rd Light Infantry did not depart until 27 December, aboard the steamer, Imperador, and on the same day the steam transport, Thames, sailed with elements of the 2nd and 3rd Light Infantry (The Times, 28 December 1855, p 10). On New Year's Day, the steam transport, Transit, left with the remainder of the 2nd Light Infantry (The Times, 2 January 1856, p 9). Meanwhile, conditions at Scutari had improved, and the sick list was falling. The Times correspondent in Turkey expressed pleasure that Wooldridge, who had been reported dead, was found after all to be alive and well (The Times, 14 December 1855, p 8). There were reports of desertions from the 1st Light Infantry, and talk of shooting some of the offenders (The Times, 28 December 1855, p 7). It was decided that the whole brigade should move to 'Kululee' (Kulali), where they would be under canvas until part of the Hospital was ready. There the two regiments celebrated Christmas Eve in the German manner, decorating their barracks with greenery and tasteful illuminations (The Times, 9 January, 1856, p 9). The Imperador arrived on 15 January with the 3rd Light Infantry under Lieutenant-Colonel W G Cameron, and on 26 January, Transit came in, having been delayed by heavy weather and an enforced visit to Vigo for repairs (The Times, 29 January, p 8, and 8 February 1856, p 9).

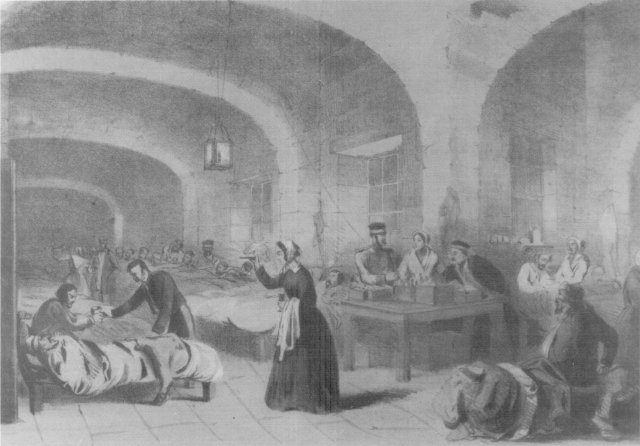

The interior of the barrack hospital at Scutari, showing Florence Nightingale at centre.

Elements of the brigade of the British German Legion were quartered here.

(By courtesy of the Director, National Army Museum, London).

The brigade spent several months at Kululee, a period that the wife of Lieutenant Alexander Gropp of the 2nd Light Infantry nostalgically recalled, nearly sixty years later, as a golden interlude. (For Mrs Gropp's lively but naive account, see www.geocities. com/Wellesley/5819/grandma.html, p 7). Three companies were detached for duty at Sinope, on the Black Sea coast, where a depot had been established for the navy. There they produced a humorous paper, The Lamp of Diogenes, named after the eponymous Cynic philosopher, a native of the place (The Times, 8 February 1856, p 9; Rodowicz). The musical accomplishments of the brigade were recognised and, when the Sultan attended a bal costume at the British Embassy, the band of the 1st Regiment marched at the head of the guard of honour (The Times, 15 February 1856, p 8). A further case of desertion was reported, involving a sergeant and seven men of the Legion who had been assigned to guard the regimental chest, containing £1 500, and had promptly absconded with it (The Times, 11 February 1856, p 10). After the Peace of Paris was concluded in March, the allies began to withdraw their troops from the Crimea and for the Germans, in their camp on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus, the sight of the steady procession of vessels - warships and transports - homeward bound with French, Sardinian and British troops must have added to the frustration they already felt on failing to reach the seat of war. To their credit, they kept their discipline, and attracted favourable comment for their part in a grand review by the Sultan on 7 April, when Stratford Canning (the influential Ambassador) conferred upon the regimental commanders the Sultan's Medidji medal (Rodowicz; The Times, 21 April 1856, p 9). They were among the last troops to leave Scutari in July, embarking on the steamers Colombo, Hansa, Ossian and Himalaya, and arriving at Portsmouth between 16 July and 1 August (The Times, 17 July, p 12; 21 July, p 9; 22 July, p 5; 23 July, p 5; 2 August [Navy & Military Intelligence], 1856).

Aftermath

For the men of the BGL, the latter part of 1856 was a period of uncertainty and mounting discontent. The regiments were quartered at camps in Aldershot, Colchester, Gosport (Browndown) and Plymouth, and did not adapt well to the tedium of barrack life in a foreign country. They developed a growing sense of grievance, misplaced possibly but real to them, about the terms of their engagement, drill, the bounty, pay and deductions. All too easily in those conditions, Satan found work for idle hands to do. In May 1856, a case of insubordination led to something close to a mutiny in the 3rd Jager Corps at Plymouth and, on 6 May, 63 men of the 6th Company were placed under guard. They had complained that their drill was too severe, and that they had only enlisted for service while the war continued. After a court martial, one man received fifty lashes and, within days, Colonel John Kinloch, Inspector General of Foreign Legions, announced the regiment's disbandment (The Times, 10 May 1856, p 11; 17 May 1856, p 10. The 3rd Jagers were raised in North America amid official opposition). On 21 June, there was an affray at Aldershot, involving men of the 2nd Jagers and soldiers of the Rifle Brigade. Knives, sticks, stones and bayonets were used, several men were badly injured, and accusations and counter-accusations flew. There was another disturbance in Aldershot in July, shortly after the 1st Jagers returned from Turkey. A fight broke out at the Carpenter's Arms between men of the 41st (the Welsh) Foot, the 93rd Highlanders and the Jagers. It was alleged that the Crimea medals of the 41st were torn off and trampled on, officers assaulted, several men badly injured (possibly killed), and great damage done. A report from 'The Observer' carried by The Times described, with unpleasant relish, the ferocity of the struggle, likening it to Inkerman without the gunfire. The writer was at pains to identify the 1st Jagers, 'which in the dialect of Aldershott(sic) "mutinized" on board the Transit on their way to Scutari', although the Jagers had in fact travelled, without incident, aboard the Imperatrix (The Times, 19 July, p 9; 21 July 1856, p 7). The other side was put in more measured terms by Major Richard Roney of the 1st Jagers (The Times, 22 July 1856, p 5), who conceded that there had been a brawl, but defended his men, saying '[the report] detracted from a body of men with whom I have been closely associated from their first formation, and of whose orderly behaviour, obedience and respect for their officers ... I have ample and gratifying proofs.' There was an enquiry, but tempers having cooled, the German officers refrained from laying charges against the British, while the latter 'could not say' who was in the wrong (The Times, 25 July 1856). A liberal coat of Aldershot whitewash had been applied, but the events had added urgency to the need for useful employment, preferably far away, for the German Legion.

Like the curate's egg, the legionaries were good in parts, but their detractors preferred to dwell on their failings, some assuming with alacrity that the foreigner was always to blame. One of these detractors was Clarendonb, the Foreign Secretary, who in a letter written at Balmoral told Panmure with undiplomatic bluntness that 'your letter affords the most satisfactory prospect we have yet had of getting finally quit of our Legionary plagues' (Douglas & Ramsay, Vol II, p 295). By this time even Cambridge, who previously had championed them, was keen to see them go, telling Panmure that there had been much rioting at Colchester, now subsiding, and that 'at Browndown there has been a most unpleasant occurrence' (Douglas & Ramsay, 1908, Vol II, p 313).

The incident in September at Browndown, outside Gosport, was a considerable affair, involving an allegation that an officer of field rank had disobeyed the order of a superior. Lieutenant-Colonel Adolf von Hake, a colourful figure, now sixty-four years of age, had, it was said, served under Blucher at Jena in 1806 (at the tender age of fifteen), and saved his regiment's colour. He was with Blucher again at Waterloo, where he had had two horses shot under him and won the Iron Cross. In the Schleswig-Holstein War, he had been a staff-captain in the Freikorps under General von der Tann, and later commanded an infantry battalion. During his eventful career, he had had more than one brush with authority, but his conduct in the face of the enemy had been exemplary. The men of his regiment in the BGL gave the old warhorse, with rueful affection, the nickname 'der alte Dauerlauf' (literally 'endurance run', but perhaps colloquially 'Old Route March') because of his devotion to strenuous route marches as a form of training (Bayley, 1977, pp 151-2; Rodowicz; Parkinson, 2001, p 66. Parkinson places Blucher not at Jena, but at the major engagement fought at Auerstadt [20km away] on the same day, 14 October 1806). True to form, Blucher now fell out with his superior, Wooldridge, was accused of disobeying an order, and placed under arrest. Men of his regiment attempted to release him, threatened to shoot Wooldridge, and attacked a police station (PRO W03/329, memorandum from the Horse Guards, Maj-Gen G A Wetherall [Adjutant General] to Military Secretary, 26 November 1856). The charges were serious disobedience, mutinous conduct, an attack on the civil power, and armed threats to an officer - and the after-shocks rumbled on into the autumn.

Meanwhile, the Government had been anxiously seeking an honourable solution that would free them of this increasingly troublesome burden, hampered by the fact that for many of the legionaries a return to their homes in Germany was not a realistic option. They were only partly successful: some legionaries did indeed return to their homes, some settled in Britain, others emigrated to the Americas, and when the Government finally produced a scheme for their future employment only a rump of the Legion - fewer than 25% of their original strength - took advantage of it.

Notes

a According to a memoir by a German officer of the Legion, Wooldridge did not speak German - see Wolbert G C Smidt, 'Schleswig-Holstein und das Osmanische Reich: Ein vergessenes MemoirenWerk von Theodor Rodowicz von Oswiecimski erhellt Schicksale schleswig-holsteinischer Offiziere nach 1848', in Familienkundliches Jahrbuch Schleswig-Holstein, vol.42, 2003, pp 66-97 [Rodowicz]. Wooldridge's background was unusual. He came from a naval family, but as a young man served in Spain with a British Auxiliary Legion raised for service in the Carlist Wars, and commanded by Lt Col Sir George de Lacy Evans. He was promoted to the rank of major in the 4th Infantry Regiment of the Legion in 1836, and later to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He does not seem to have served in the British Army until his appointment to command a brigade of the BGL in 1855.

b Clarendon was even more severe about the troublesome Italian Legion, saying ' ... the Argentine Confederation is the place to look to for the Italians. They would meet there with what is congenial to their tastes, fine climate, cheap provisions, abundance of land, and an unsettled government, and we should have the advantage of an unpassable ocean between them and England. '

Bibliography

Bayley, C C, Mercenaries for the Crimea, (Montreal, 1977).

Dictionary of Welsh Biography Down to 1940 (London, 1959).

Douglas, G & Ramsay, G D (ed.), The Panmure Papers Vols I and II (London, 1908).

Ellis, E L, The University College of Wales Aberystwyth, 1872-1972 (Cardiff, 1972).

Engels, F, 'The Armies of Europe', in Putnam's Monthly Magazine, 6 (Aug 1855).

French, J H & Kinsey, H W, 'Baron Richard von Stutterheim', in Military History Journal, Vol 3, No 4 (December 1975).

Parkinson, R, The Hussar General (Wordsworth, 2001).

Smidt, W G C, 'Schleswig-Holstein und das Osmanische Reich: Ein vergessenes MemoirenWerk von Theodor Rodowicz von Oswiecimski erhellt Schicksale schleswig-holsteinischer Offiziere nach 1848', in Familienkundliches Jahrbuch Schleswig-Holstein, Vol 42, 2003,

pp 6 697 [Rodowicz].

18&19 Vict c 2.

Public Record Office [PRO], W06/196 & W03/329.

Simner Family Papers [SFP], now in the custody of their descendant Mrs Wendy Roderick, and referred to with her consent.

www.geocities.com/Wellesley/5819/grandma.html. p 7.

King William's Town Gazette, 8 April 1872.

The Times, 3 July 1855 - 2 August 1856.

CORRIGENDA as published in Vol 13 No 3, June 2005

Part 1: "'By Her Majesty's Command" - Ensign Simner's Commission', (Military History Journal, Vol 13 No 2, December 2004, pp 60-5): Readers, please note the following editing error which appears in the sentence beginning 'True to form, Blucher now fell out with his superior, Wooldridge .. .', p 65, column 1, line 19. This should, of course, read 'von Hake', not 'Blucher'. Blucher died in 1819. The editor apologises for the error.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org