The South African

The South African

Dr Moller is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at the School for Basic Sciences, Vaaltriangle Campus, North-West University (PUCHO Potchefstroom), South Africa. He has also lectured at the Military Academy, a faculty of the University of Stellenbosch and researched many aspects of military history. He has read papers at national and international conferences and has published several articles. Research for the following article was conducted at archives repositories in South Africa, Britain, and the United States of America.

SAAF Liberator in flight, 1944

(Photograph supplied by courtesy, SANMMH).

Soon after the German occupation of Poland in September 1939, Polish liberation movements were formed to co-ordinate all resistance activities against the Germans. On 1 August 1944, the Polish partisans led an uprising in Warsaw and occupied major sectors of the city. The Germans reacted quickly and isolated the areas occupied by the partisans. Owing to the fact that the Russian forces abruptly stopped their advance towards Warsaw, the situation in the city itself soon became desperate for the partisans. They needed armour and ammunition, as well as medical supplies.

On 3 August 1944, the Polish partisans in Warsaw called for urgent help from the Allies. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to send assistance. He ordered 205 Group, commanded by a South African officer, Brigadier J T (Jimmy) Durrant, to start with extensive flights to Warsaw, despite the extremely difficult circumstances that would seriously hamper these supply flights. 205 Group included 1 586 Special Polish Duty Squadron, 178 and 148 Squadrons (334 Wing) Royal Air Force, and 31 and 34 Squadrons (2 Wing) SAAF. This operation became known as the Warsaw Airlift, also referred to as the 'Warsaw Concerto'.

The flights to Warsaw took place from 13 August to 22 September and represented a round trip of 2 815km. For the greater part of this distance, the aircraft flew over enemy territory and in broad daylight, although they were timed to reach the city in the dark. The aircraft did not fly in close formation, although they left at approximately the same time. In close formation, enemy searchlight batteries would have spotted them and pinpointed them more easily as targets for German night-fighters. They would also have been intercepted more easily. Only the Americans flew in close formation to Warsaw because they enjoyed the protection of P51 escort fighters. This they did on 18 September.

The route from the Italian bases extended from Celone or Foggia to the Adriatic Sea. From there they crossed the Scutari Lake in Albania, flew north over Yugoslavia, across the Danube to Hungary and Czechoslovakia and then over the Carpathian Mountains. Pilots then had to follow the Vistula River for the last leg to Warsaw. Supplies had to be accurately dropped on identified street areas or into specified air-supply zones.

The Liberator bomber used for this exercise weighed 25 480kg (28 tons) and was equipped with four engines, each developing approximately 150kW. Each aircraft carried twelve 150kg metal containers, a total of approximately 1 800kg. Fuel capacity was roughly 9 000 litres. The aircraft could fly a distance of 3 714km and were armed with ten half-inch machine guns.

Only a small amount of ammunition and arms could be carried on each flight since the larger part of the carrying capacity of the aircraft was taken up by fuel. Usually, during ordinary flights, the calculated fuel reserve would be 25% to account for possible emergencies. For Warsaw, the estimated reserve was only nine percent.

The risk of enemy fire or interception over such a long flight distance caused great stress and anxiety amongst the aircrew. Many aircraft were damaged so badly that they had to carry out forced landings. Others were shot down by night-fighters or antiaircraft guns. For most of the flight, navigators were unable to communicate with radio transmission from ground stations, owing to these being out of range. Pilots had to be on the alert to spot high mountain ranges.

On reaching the Vistula, the aircrews would became aware of a dim glow on the horizon. As they approached, it would slowly become bigger until it developed into a bright inferno. This was Warsaw burning. Owing to the thermal effects of the fires in the burning city, the aircraft would shake wildly as they flew over at approximately 350 metres. The hot air and smoke inside the aircraft would become almost intolerable. The fires that lit the sky would make the aircraft easy targets for enemy machine guns positioned on the rooftops. Pilots might be blinded by searchlights. The air would be streaked with tracer bullets, and when a Liberator exploded after a direct hit, it would appear as a small spark against the fiery background.

When Liberator EW1 05 G, commanded by Lt R R Klette, arrived over Warsaw, it was immediately caught in the bright beams of searchlights for approximately fifteen seconds and bombarded by anti-aircraft batteries. Bullets penetrated the fuselage and caused several onboard fires. Three of the four engines were hit and burst into flames, causing a severe fire which threatened to destroy the fuselage. The damaged engines were switched off and the fire-extinguishing systems switched on. The pilot succeeded, with great difficulty, in flying away from Warsaw in a south-easterly direction.

As their altitude was too low, it was impossible for the crew to use their parachutes. They were still flying over densely built-up areas when a clearing suddenly appeared and Lt Klette decided to use the opportunity to make a forced landing. The Liberator finally landed on its fuselage and scraped forward over the ground for several hundred metres. To the crew's amazement, they found that they had landed in the middle of Warsaw's main airfield, which was not in use at the time. Not one of them was injured.

Another outstanding example of bravery was that of Liberator KG 872 V, commanded by Captain W E Senn. It was hit by anti-aircraft fire, and Captain Senn was seriously wounded in the thigh. The mid-upper gunner was hit in the hand. The rudder control cable of the Liberator was damaged; the elevator control was partially cut; and the hydraulic mechanism of the nose wheel was put out of action. Fuel began to leak, which increased the fire hazard. Instruments, as well as the intercom system, were put out of action. Meanwhile, the tail gunner continued firing at the searchlights and shot out four of them.

Captain Senn then gave the preliminary order to the crew to prepare to jump. They did not realise that he had been wounded, and would therefore crash with the aircraft. The buckle of his parachute had been shattered. A fire broke out in the navigational compartment shortly afterwards, but was extinguished by the crew. One of the fuel tanks was shot to pieces, which forced the pilot to reduce speed in order to save fuel. This increased the danger of being shot down.

The 1 450km flight home, without maps and using only the automatic rudder control, was extremely stressful. The Liberator reached the Danube at daybreak, and went on to land safely at Foggia. Captain Senn's crew was at no stage aware that he had been wounded.

Lt J C Groenewald was co-pilot of Liberator EW 248 P on its second flight to Warsaw on 16 August 1944. Of all the narrow escapes during these sorties, his experience was certainly among the most surprising and dramatic. His Liberator reached Warsaw just after midnight. During the flight over the burning city, the aircraft was caught by searchlights and engaged by anti-aircraft fire. Hit several times, it soon became engulfed in flames. The pilot, Major I J M Odendaal, ordered the crew to bail out.

As Groenewald grabbed his parachute, the Liberator was hit once again, and virtually blew up. Groenewald was hurled into the air by the violence of the explosion. He found himself falling with his parachute still clasped like a suitcase in his hand. Fortunately, he kept his presence of mind and managed to fasten the parachute to its harness and pull the rip-chord. He landed uninjured, except for burns to his face and arms.

Using the parachute as a blanket to keep warm, Lt Groenewald spent the rest of the night in the German-controlled area at the spot where he had landed. At daybreak, he succeeded in stumbling to a farmstead, about 2km away. There, a sympathetic Pole took care of him and hid him under some hay. He was taken by horse-cart to a well-equipped little hospital, run by an old professor who had earlier been a lecturer at Warsaw University. Nurses, disguised as farm labourers, manned the hospital. Groenewald was treated there for ten days, during which several skin grafts were performed on him by a Polish surgeon. When he had completely recovered, he was provided with false identity documents and, disguised as an old Polish farm labourer who was too old for military service, he worked on a farm as a foreman. His new name was Jan Galles.

Later, Groenewald joined the Polish partisans and fought with them against the Germans. In February 1945, six months after his Liberator had been shot down, Russian divisions reached the area where Groenewald fought. He was taken to Moscow, where he was handed over to the British Military Legation. From there, he was able to send a cable to his wife, who had been receiving a pension from the widow's fund for several months.

The events surrounding the flight of Liberator EW 138 K, with Lt W Norval at the helm, make it surely one of the most dramatic of the Warsaw flights. It is an excellent example of the extreme stress experienced by the aircrews. On arriving over Warsaw, this Liberator was caught in the beams of a group of ten to twelve searchlights and came under heavy anti-aircraft fire. After a few terrifying moments, Lt Norval succeeded in escaping the lights. But then, without uttering a word, he grabbed his parachute, opened the doors of the bomb bay, and jumped.

The Liberator went out of control and began to lose height as it moved to and fro across the Vistula. The co-pilot, Lt R C W Burgess, succeeded in regaining control only 303 metres above the ground. However, a glaring light in the cockpit indicated that the bomber was once again caught in searchlights. The gunner in the forward turret continued firing at them and succeeded in eliminating them, one after another, until Lt Burgess managed to pilot the limping aircraft away from the burning city.

The compass was out of order, the instruments were defective, and one of the engines had died. The badly damaged aircraft was controlled only with difficulty, and constantly threatened to nose-dive. A fuel problem was overcome when one of the crew, with great difficulty, made his way to the fuel tanks in the fuselage via a narrow bridge, which was then slippery because of leaking oil. Although in constant danger, he managed to pump fuel to the main tanks. Then the propeller of the damaged engine suddenly began to turn uncontrollably, causing the bomber to dive towards the ground at a speed of 435km/h.

With great effort, Burgess succeeded in regaining control at an altitude of only 900 metres. At daybreak, they flew over a village that had an old airfield and Burgess decided to attempt a landing. The aircraft circled the village eight times while the crew struggled to get its undercarriage and air brakes into operation. On the ninth approach, the aircraft landed successfully.

SAAF Liberator in flight, 1944

(Photograph supplied by courtesy, SANMMH).

As far as the Warsaw Airlift is concerned, however, a military lesson is to be learned from this episode: Adventurous initiatives which are unlikely to work should not be undertaken for purely political motives. The flights undertaken from Italy were conducted under the most hazardous circumstances and, as indicated very clearly in the individual flight reports, the crews were battling against overwhelming odds. Their objectives were unrealistic and militarily catastrophic. Seen from a military perspective, this was a reckless operation and should never have been attempted.

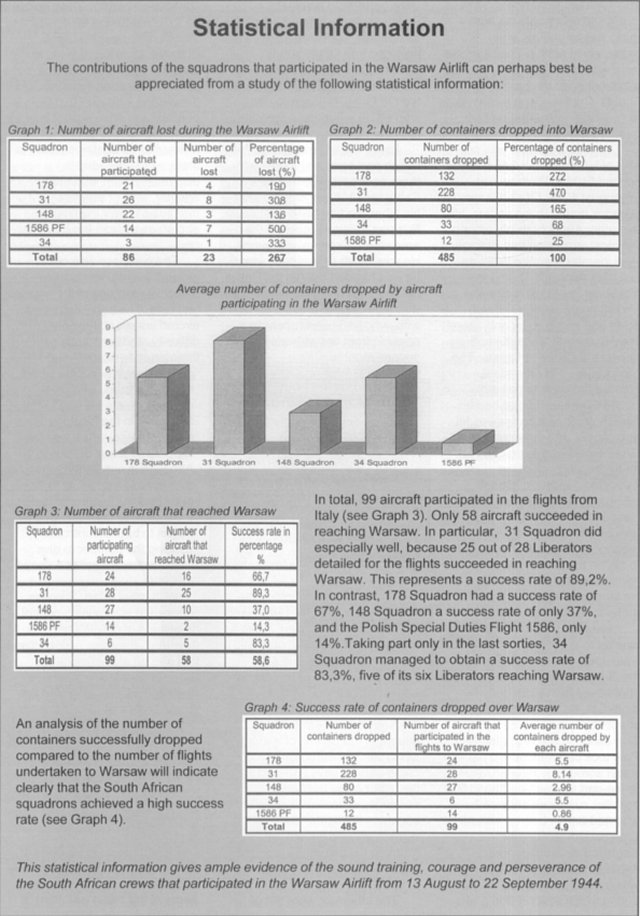

The airlift was, in many instances, futile and utterly senseless. When Bor-Komorowski surrendered to the Germans, the partisans had tried for 63 days, in vain, to liberate their capital. Of the approximately 40 000 men and women who were members of the underground army, roughly 18 000 lost their lives, about 25 000 were wounded (6 500 seriously), and the total number of civilian casualties was estimated at 180 000 people (The Citizen, January 1978, K Swaift, 'Death and destruction in the skies', p 5). Nevertheless, the airlift invokes feelings of deep respect for the aircrews who participated in the flights to Warsaw and risked their own lives.

The Warsaw operation resulted in a firm bond of friendship between the crew members who took part jn the task flights to Warsaw and the Polish community in South Africa. The Warsaw Airlift is, therefore, important from a cultural-historical perspective.

Conclusion

Today, the aircrews are honoured for their brave actions when the Polish community gathers in Johannesburg in September every year to commemorate these events. Squadrons are widely praised for the courageous conduct, perseverance and sense of duty which they exhibited whilst participating in the Warsaw Airlift. Several individuals received awards for gallantry, including the Distinguished Flying Cross. Both strategists and statesmen have commented on these operations. In his book, The Central Blue (1956, p 621), Air Marshal Sir John Slessor refers to the Warsaw flights as 'a story of the utmost gallantry and self-sacrifice on the part of the aircrews who participated'. Josef Garlinski (1969, p 206) says that 'the great sacrifice of the young men who died with the full knowledge that their death could not alter the course of the events, is an example of the utmost heroism', and Winston Churchill (quoted by L Capstickdale in South African Panorama, Nov 1980, p 44) describes the courageous conduct of these air crews as 'an epic of human courage'. It is one of the tragedies of war that sacrifices like those of the Allied airmen who gave their lives to assist their Polish allies were ultimately in vain.

Bibliography

Anon, 'SAAF heroes in Warsaw Airlift' in Paratus, 34(9), September 1983.

Blake, A, 'Die vlug na Warschau' (unpublished document, File B421, SANMMH, Johannesburg, 1981).

British Ministry of Defence, London, Air Historical Branch, London, File 13: Air supply for Warsaw, n.d.

Capstickdale, 'Warsaw: A South African epic' in South African Panorama, November 1980.

Churchill, W S, The Second World War: Triumph and Tragedy (London, Cassell, 1948).

Garlinski, J, Poland, SOE and the Allies (London, Allen & Unwin, 1969).

Isemonger, L, 'Target Warsaw: The Story of South Africa's First Heavy Bomber Squadron'

(unpublished document, Library, SANDF Documentation Centre, Pretoria).

Martin, H J & Orpen, N D, Eagles Victorious (Cape Town, Purnell, 1977).

Orpen, N, Airlift to Warsaw: The rising of 1944 (New York, Foulsham & Company, 1984).

Personal interviews with J L van Eyssen (15 August 1983), R R Klette (by telephone, 13 December

1984), J R Coleman (7 December 1984), R C W Burgess (7 December 1984).

Siessor, J, The Central Blue (London, Cassell, 1956).

Swaift, K, 'Death and destruction in the skies' in The Citizen, January 1978, p 5.

War Diary, SAAF, Container 44, File 1 (SANDF Documentation Centre, Pretoria).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org