The South African

The South African

This article is based on the author's MA research report, 'Robben Island's Coastal Defence, 1931 - 1960', completed at the University of the Witwatersrand, Department of Political Studies, in 1998. The author has recently completed her PhD, also at Wits, entitled 'Land Reform, Equity and Growth in South Africa: A comparative analysis.'

Robben Island's first military purpose was to replace HMS Erebus as a static battleship. On 23 March 1939 it was announced that, from 1 September the monitor Erebus, armed with 15-inch guns, would defend Cape Town. This was arguably necessary because it would take at least four years for the required coastal guns to arrive in South Africa. The intention was to station HMS Erebus close to Robben Island where it would serve to protect the ships in Table Bay Harbour until fixed armaments had been established on the island. However, the Erebus was never used. She was unsuitable for the rough seas around the Cape, and a blast from one of her 15-inch guns could have caused more damage to Cape Town than any enemy battleship. Following the recommendations of the 1928 Imperial Defence Commission, it was decided that a high-angle, 9,2-inch gun battery would be established on Robben Island instead. Thus the island assumed its first military role as a static battleship in the place of the monitor Erebus.

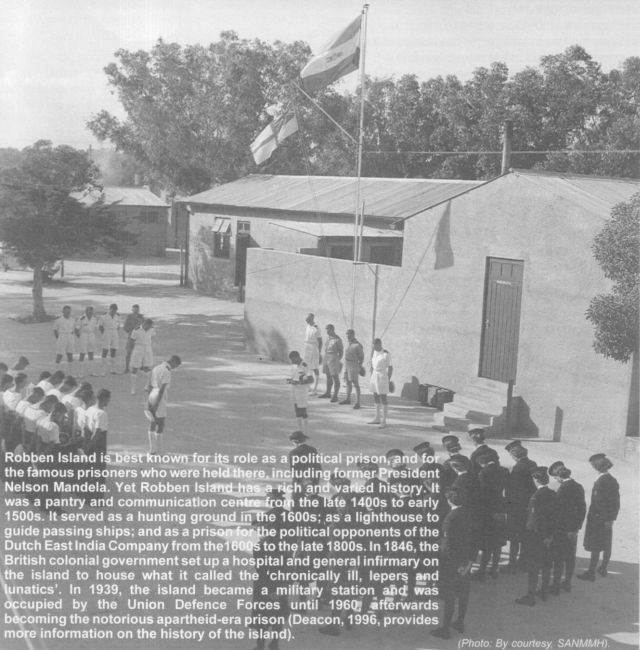

ASWAAS rangetakers in BOP (Battery Observation Post)

Robben Island (From Hill, Look in after 40 years).

Members of the South African Engineer Corps (SAEC) arrived on Robben Island in 1939, to conduct a preliminary survey before construction and fortification could begin. At the time, the island was a virtual wilderness, but within a few years the military had constructed a comfortable settlement for 3 000 people. Fortification involved conveying 150 000 tons of equipment and material to the island, clearing trees and building roads, a harbour, gun emplacements for two batteries, underground magazines and plotting rooms, observation towers, accommodation for thousands, recreational facilities, a runway and more. Old buildings were also renovated. The last building to be completed during this period was the John Craig Recreation Hall.

There were also approximately 2 000 workers on the island. Some estimates put the figure as high as 5 000. A large percentage of these workers were African labourers who were accommodated in a specially created compound separated from the rest of the island's inhabitants. Until 1942, the labour force and some of the engineers were civilians, but in that year all civilians were evacuated in fear of a Japanese attack. The South African Engineer Corps became responsible for all future construction work.

There was no harbour on the Island, only a small jetty at Murray's Bay. This was inadequate for the transport of the necessary personnel and equipment, including 30-ton gun barrels, radar and Asdic equipment, steam rollers for the runways, material for the degaussing range, and building materials. Although the first priority of the engineers was to build the gun emplacements, this could not be done until a new harbour had been provided. The new Murray's Bay harbour was eventually built with stones from the former leper hospitals. It took almost two years to complete.

Work began in June 1939 on the gun emplacements and accompanying military buildings. According to the plan, a 6-inch battery (Cornelia) and a 9,2-inch battery (Robben Island) would be situated on the northern and southern sides of the island respectively. By April 1940, work had advanced sufficiently to allow for the installation of the first 6-inch guns at Cornelia. Although this battery only became operational in July 1940, personnel were drafted there immediately. In May and June 1942, the first 9,2-inch gun was mounted at the Robben Island battery. November 1942 saw the installation of the second 9,2inch gun there. The battery was operational by the end of the year. The third 9,2-inch gun was installed only in 1945. Constructing the gun emplacements also implied building their ancillary points, such as observation posts, a power station, plotting rooms, and magazines. Most of these were 30ft (about 9m) underground.

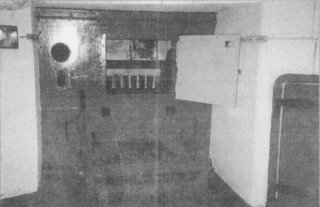

The chain loading system for Robben Island

No 1 Gun, Mk 9. (Photo: Maj Gordon, 1997).

In addition, the island's perimeter had to be fortified. This included the provision of machine gun posts, searchlight stations and barbed wire barriers. By 1940 all was complete. In March 1942 it was also decided to prepare the island against attack from Japanese landing craft. So began the construction of pill-boxes and rifle posts at strategic points.

Accommodation for an estimated 3 000 people had to be constructed. This entailed the provision of separate accommodation for white male soldiers, Coloured male soldiers, female artillery specialists, and female naval personnel. In addition, a mess had to be built, plus naval wardrooms, religious and recreational facilities, a hospital, a hall, sewerage disposal and electrification works, a shop, a bakery, and even a library. It was also deemed necessary to duplicate many of the facilities to meet the ideological requirements of racial segregation. There was no water supply on the island, and five successful boreholes were sunk. Construction of the airfield began in 1940. A domestic power station also had to be built.

With its long coastline, and strategic location at the southern end of Africa guarding the passage between the Atlantic and Indian oceans, South Africa's military preparations had to involve the defence of the coastline and harbours. The closure of the Suez Canal had increased the volume of shipping around the Cape, and the ships needed a safe harbour where they could refuel and undergo repairs. At the height of the war, there was a daily average of fifty ships anchored in Table Bay harbour. Given the absence of a large naval force, fixed coastal defences were seen to be absolutely crucial.

As a result, former coastal batteries were improved and new ones built at Llundudno, the Cape Town docks, Gordon's Bay, Simon's Town, and on Robben Island. This long line of coastal batteries protected the South African coast from about Jacob's Bay, north of Atlantis, right around to Cape Hangklip, including the False Bay area. The powerful gun batteries at Simon's Town, Llundudno and on Robben Island formed the Cape Peninsula's main defences. These batteries were also designed to support each other. Hence, the 9,2-inch gun batteries would overlap to cover the entire coastline and, in particular, the harbour.

The principle function of the batteries on Robben Island was to protect both the approaches to Table Bay harbour, and the harbour itself. The 6-inch battery's role was the close defence of the harbour, and later also the adjacent degaussing range in the Blouberg Channel. The primary role of the Robben Island 9,2-inch battery was to keep sea raiders at a safe distance from Cape Town and the other large coastal towns. These high-angle 9,2-inch guns, with an average range of 30 000yds (27 420m), became the mainstay of the island's defences. They gave Cape Town an advantage over enemy battleships because they were placed well forward. Yet, battleships normally mounted 15-inch guns with a range of 50 000 yds (45 700m), so they could usually out-range the coastal defence guns. By building the 9,2-inch battery on Robben Island, the guns were actually 'out at sea'. Thus the importance of the Robben Island battery was that it could target a battleship before it was close enough to inflict damage on the Cape Peninsula's coastal towns, or on Table Bay harbour. A second advantage was that although these guns were out at sea, they were far more accurate than guns of a similar capacity on a battleship. This meant that a whole convoy could safely be anchored at Table Bay harbour, defended by the Robben Island guns.

A secondary, but also crucial role played by these guns was as a training establishment for coastal and anti-aircraft gunners. Robben Island continued in this capacity until May 1942. The training depot then became the Coastal Artillery School and remained operational until 1944. In January 1944, all operational personnel on the Robben Island batteries were withdrawn, and the two batteries themselves were placed under care and maintenance.

At the beginning of the Second World War, battleships and surface raiders were seen as the biggest threat to South Africa's coastal towns and harbours and coastal defence lay with the South African Artillery in the form of coastal batteries. Towards the latter half of the war, submarines and deadly German magnetic mines became the major threats. The emphasis of coastal defence thus shifted to underwater and other fixed defences. The naval fixed defences for the Cape Peninsula were concentrated on and around Robben Island. The degaussing range was established on the eastern side, in the Blouberg Channel. Robben Island also became the control centre for the submarine detection cable, indicator loops, and other Asdic defences. The degaussing range dealt with an estimated 3 156 ships.

ASWAAS rangetakers on top of the

Battery Observation Post (BOP) Robben Island

(From: Hill, Look in after 40 years).

The coverage provided by radar installations at Signal Hill and Blouberg in the immediate vicinity of Robben Island proved to be inadequate. Short-range radar was thus established on the island in January 1943. Eight female Special Signals Service (SSS) personnel operated the radar system. The purpose of the radar coverage was the detection and tracking of all aircraft, ships, small surface craft and surfaced submarines. Radar was also useful for directing and guiding friendly ships in bad weather or at night. For example, on 9 December 1942, radar detected a 6 ODD-ton vessel about to go aground in heavy fog. The island foghorn successfully warned it off.

Robben Island also played a role in anti-aircraft defence. Two anti-aircraft searchlight posts were located there. Coastal area squadrons also used the landing strip when they ran out of fuel, or encountered other difficulties while on patrol. When Cape Town had its first air raid alarm on 24 November 1941, it was a gun position on Robben Island that first detected and reported the presence of three unidentified, possibly enemy, aircraft.

The coastal defence system was extremely costly, involving hundreds of thousands of pounds. Yet these coastal batteries were never required to fire a shot in anger. Was the expense justified? It can be argued that it acted as a deterrent, and was justified given the importance of South Africa's harbours as safe anchorages for Allied ships to refuel or undergo repairs. It was also the case that many of South Africa's major towns were close to these ports, and were thus especially vulnerable to German and Japanese submarines and surface raiders.

Intense submarine activity and numerous sin kings accompanied the vast increase in the amount of shipping around the Cape during the war. Eighty-one Allied ships were lost in, or close to, South African waters. Perhaps the most dramatic incident was the attack on the German ship, the Watussi, off Cape Point. The Graf Spee was another notorious German warship active in South African waters. By 1942, the Mediterranean had become a battleground, and huge convoys carrying reinforcements and war material were rounding the Cape in a constant stream. Altogether, between 1941 and December 1944, 49 241 ships visited this country's harbours.

German control of Cape waters might have severed the Allied route to the Middle and Far East. The German Navy sent four U-boats in August 1942 to attack shipping in South African waters. On their way to the Cape, they sank the troopship Laconia carrying 1 800 Italian prisoners of war, on the west coast of Africa. On 5 October, the U-68 was 40km off Cape Town, within view ofTable Mountain. That same night, Cal?tain Karl Emmerman, commander of U-172, headed for Table Bay. He stopped within hailing distance of Robben Island, studied the harbour installations and, before submerging again, allowed his crew to come 'up, one by one, to enjoy the magnificent sight of a city unconcerned with wartime black outs'. Emmerman brought his U-boat even closer, and lay at periscope depth between Robben Island and Green Point, awaiting orders to attack. On 7 October, he sank the Firethom and the Chickasaw City, only 96km from Cape Town. In the next few days, his fellow U-boat commanders sank another eight Allied ships.

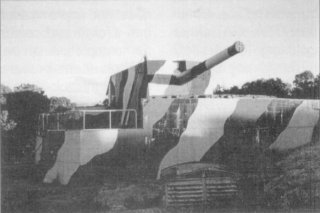

Robben Island No 2 Gun, Mk 7, De Waal Battery.

(Photo: Maj Gordon, 1997).

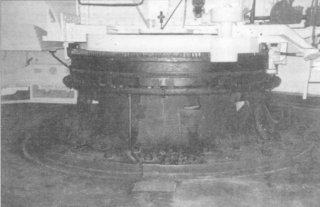

Robben Island No 2 Gun mounting mechanism.

(Photo: Maj Gordon, 1997).

Robben Island No 2 Gun, top of ammunition hoist.

(Photo: Maj Gordon, 1997).

The period between October 1942 and March 1943 saw German submarines take a heavy toll of ships sailing out of convoy in South African waters. In the first four days of the German submarine offensive launched in October 1942, twelve merchant ships were sunk. By late 1942, South African naval forces had rescued over 400 survivors. The greatest individual success gained by a submarine in South African waters was that of U-160. In one night, it torpedoed six ships in a convoy 80km from Durban. In 1942, Japanese submarines sank 21 ships, mostly in the Mozambican Channel and one only 118km from Durban.

Early in 1940, enemy minefields were laid off Cape Agulhus, on the main shipping route around the Cape. Others were laid in the approaches to Table Bay. The German raider, Doggerbank, laid 60 mines only 35km west of Table Bay harbour and another fifteen 8km from Cape Agulhus. The Atlantis laid 92 mines between 8km and 37km from Cape Agulhus.

The first group of military personnel to arrive on Robben Island in September 1939, were representatives of the Directorate of Coastal Works and Fortifications, members of the South African Engineer Corps (SAEC) and gunners of the South African Permanent Garrison Artillery (SAPGA). Other military staff soon followed, including the Artillery Specialists of the Women's Auxiliary Army Service (ASWAAS), the South African Women's Auxiliary Naval Service (SWANS), and Coloured gunners from the Cape Corps. Some of these were to serve on the island itself, and hundreds more were trained as coastal and anti-aircraft gunners on the island. Chaplains, medical and hospital staff and members of the Military Police were also resident there. A further group of South African naval personnel arrived later to operate the degaussing range and other fixed defences. There were at least 2 000, mainly black, labourers resident on the island until 1942, when civilians were evacuated. In addition, Vichy French prisoners of war were incarcerated there.

The contribution of the Cape Corps to the war effort has, until recently, been neglected and distorted in mainstream South African history. A study of Robben Island during this period disproves the myth that men from the Cape Corps served in a non-combatant capacity only. The basic reason for this was the Union Government's policy on 'non-European' military service. Section 7 of the Defence Act of 1912 stipulated that 'non-whites' could only be called up in a non-combatant capacity. However, reality made adherence to ideology impossible. South Africa had very limited manpower and it soon became apparent that many units could not be maintained unless non-Europeans were utilised. Smuts announced that due to 'circumstances prevailing in South Africa' he had no choice other than to bring non-Europeans into the armed forces. He insisted that 'it was out of the question to arm them'.

On 25 May 1940, the Union Government officially gave permission for members of the Cape Corps to re-enlist for service in the South African armed forces. Officially, the Cape Corps did not serve as a combat unit, but rather in supportive and logistic capacities. Unofficially, some Cape Corps men were armed and trained to serve as garrison troops and to guard prisoners of war. Coloured servicemen also served in the South African Naval Service. Over 8 000 Coloured men were trained to work on minesweepers and similar vessels. All Cape Corps recruits underwent training in musketry and rifles, and approximately 2000 of them were trained as anti-aircraft and coastal gunners on Robben Island. On completion of training, they either served as gunners there, or were sent to North Africa as active combatants.

It was as a result of manpower shortages that this unique establishment on Robben Island was formed. White gunners were irritated at being kept back to man coastal batteries. The problem became more acute when the two light anti-aircraft regiments already in the field in Egypt started demanding reinforcements. A policy for the 'dilution' of coastal defences was thus decided on. Accordingly, the Director of Coast and Anti-Aircraft Artillery was ordered to accept Cape Corps men for training as coastal gunners. By September 1940, 2 000 men were concentrated at the Anti-Aircraft Training and Reserve Depot on Robben Island, ostensibly to release white gunners for a third anti-aircraft regiment.

After the extensive training received on Robben Island, men from the Cape Corps were deployed as garrison troops inside and outside Union borders. Approximately 1 000 of them were selected to serve in the Seaward Defence Force as ratings on minesweepers and harbour defence launches on the South African coast. There were also some 350 Cape Corps men stationed on Robben Island itself, manning the two gun batteries. Before the end of 1941, at least 600 Cape Corps men who had been trained on Robben Island had been drafted to join the 2nd Division Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the Middle East just in time for the battle of Bardia. Another 300 joined South Africa's only two anti-aircraft regiments ever to see any real action against the German Luftwaffe.

Men from the Cape Corps, however, had a relatively negative experience on the island. This included ill-fitting uniforms, no mess, segregated accommodation in tents, lower salaries, and smaller pensions. Cape Corps men could not be promoted above the rank of warrant officer first class, and would thus perform duties without receiving the appropriate rank or pay.

The Artillery Specialists (AS) was established as a branch of the Women's Auxiliary Army Service. These women served in gunnery and as radio specialists at various coastal batteries and defence locations around the coast. They were trained at the gunnery school on Robben Island. The ASWAAS was formed in order to release white men for service in North Africa, and their personnel were responsible for range-finding operations. This included close and long-range coastal defence. Close defence meant the protection of the waters surrounding Cape Town and the outer harbours and ports. Long-range defence involved attacking the enemy further out at sea. The women were also trained to operate the battery guns. More than 400 female artillery specialists were trained on Robben Island. By early 1944, ASWAAS personnel had been trained to operate the searchlights on the island as well.

As soon as training was complete, the women would be assigned to various coastal defence stations around the South African coastline, including Robben Island. One of the most important duties performed by ASWAAS personnel on the island itself was working in the underground plotting rooms. These rooms, 30ft (9m) underground, contained the plotting tables and all the other specialised equipment necessary for converting the range and bearing information received from the observation posts into range and bearing for the guns. The basis of their work was 'cross observation'. This involved duties at the Fortress Observation Post. Operators at the two observation posts would track a ship with binoculars and relay its course to the batteries at regular intervals. Daily routine involved adjusting the observation instruments to sea level by means of a datum post.

Specially trained, the SWANS worked at harbour defence. Technical training courses were given on Robben Island. On the island itself, SWANS were responsible for anti-submarine fixed defences, Asdic defences and watch duties, which included Visual and Hydrophone Watch. On Visual Watch at the Battery Observation Post, SWANS would observe the traffic between Robben Island and Table Bay on a 24-hour basis, identifying all passing ships. This duty was necessary because the instruments used for the detection of midget submarines were very delicate. A large ship passing over the detection cables and equipment could give the instruments a jolt and put them out of action for dangerously long periods. On Hydrophone Watch, operators wearing headphones worked in what was called the 'ha-de-dah' room. Operators would listen to the sound of Asdic 'pings' that would indicate the presence of a midget submarine. In the 'Loop Room', recorder rolls were placed along the wall and operators checked the tracing on the recording needles. Variations could indicate the presence of an enemy submarine.

By May 1945, military operations on Robben Island had already been scaled down. Most ofthe operational personnel had left the island by late 1944. A Coastal Artillery care and maintenance unit was given the responsibility for keeping the guns and the buildings in order.

The Coastal Artillery School on Robben Island recommenced activities on 1 February 1946, as a Permanent Force unit. A new period in the island's history was ushered in when gunners ofthe Permanent Force and their families settled there in August 1946. This coincided with the first post-war gunnery course at the Coastal Artillery School. By 1950, a decision was made to expand the South African Navy and, as a result, the Coastal Artillery School became a branch of the navy. The new unit on Robben Island was known as the Marine Corps. In October 1955, the Marine Corps was disbanded. The island then became a South African Naval Training Base, SAS Robbeneiland.

Bibliography

Brain, P, South African Radar in World War II (Newset, Durban, 1993).

Deacon, H, The Island: A history of Robben Island (David Philip, Bellville, 1996). See, in particular, pp 78-92, by A Davey, 'Robben Island and the Military, 1931-1960'.

Gleeson, I, The Unknown Force: Black, Indian and Coloured Soldiers through two World Wars (Ashanti, Rivonia, 1994).

Harris, C J, War at Sea: South African Maritime Operations during World War II (Ashanti, Rivonia, 1991).

Hill, M H, Look in after 40 years: The story of the Artillery Specialists WAAS, 1941-1945 (Marins, Johannesburg, 1986).

Laver, M P H et al, Sailor Women, Sea Women, Swans (Mills Litho, Maitland, 1982).

Mervis, J, South Africa in World War II (Whitnall Simonsen, Johannesburg, 1988).

Smith, C, Robben Island (Struik, Cape Town, 1997).

Weideman, M, 'Robben Island: Coastal Defence, 1931-1960', MA dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1998.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org