The South African

The South African

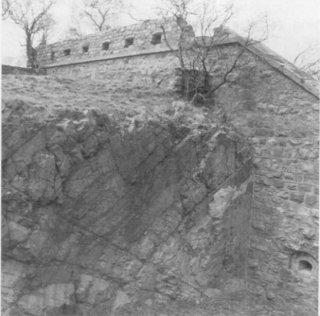

Fort Wonderboompoort, showing additional loopholes

placed above the original curtain wall by the Royal Engineers.

(Photo: Daphne Matcham, Simon van der Stel Foundation).

Thus, the Volksraad set about purchasing modern rifles and improving the commando system. Firstly, they ordered more regular wapenschauws at which members of each wyk, aged sixteen years and upwards, were going to be trained to use their newly acquired Martini Henry rifles - and, at a later date, Mausers - on proper rifle ranges, several of which were built at major centres such as Pretoria. and Johannesburg, etc. The claim that a Boer father would hand a twelve-year old a musket and one bullet and then expect him to shoot his supper and that this was the reason why Boer riflemen were far better shots than the British soldiers, was now a legend. Secondly, the Volksraad looked into the question of purchasing better field artillery and approached the French and German firms of Schneider and Krupp respectively for the purchase of modern up-to-date field guns.

However, their biggest expenditure for defence was to be on the construction of eight forts at Pretoria and a single fort at Johannesburg. The ZAR's Executive Council took the decision to build the forts in March 1896. The Johannesburg Fort was built around the existing prison on Hospital Hill. It was a novel design produced by a military engineer, Mr G H Winsen, and built by local contractors. It was intended to hold in check any rebellious movements or organisations in the town, giving the commandos time to assemble.

The Pretoria forts, however, were designed and built by the same contractors who had supplied the artillery equipments to the republic, namely Schneider and Krupp. When it became evident that the cost of all eight forts was going to be excessive, the decision was taken to build only four: Klapperkop, Schanskop and Wonderboompoort to be built by Krupp; and Daspoortrand to be built by Schneider. The steel used in the construction came from Germany, one firm being NION HORST and the other ROECHLING. (There may have been others).

All four of the Pretoria forts were earthen redoubts with bombproof rooms placed under the earth-protected ramparts. This design had stemmed from a remarkable siege which had taken place at the town of Plevna during the Turko-Russian War of 1877. A part of the Turkish Army, under the command of Osman Pasha, had rushed forward to Plevna in order stop the Russian advance. Here Osman had found a few antiquated stone forts and he proceeded to strengthen these with eighteen hastily thrown-up earthen redoubts. On the arrival of the Russian Army at the town, the stone forts were soon reduced to rubble by the Russian artillery, but the earthen redoubts proceeded to hold out for nearly five months before Osman Pasha surrendered. By that time, Russia was prepared to sue for peace. The Continental military engineers had noted, with interest, the ease with which the earthen ramparts had absorbed the Russian shot and shell. This had set a style of fortification in Europe which would lead to the adoption of this design for the Pretoria forts. All four forts were completed by 1898.

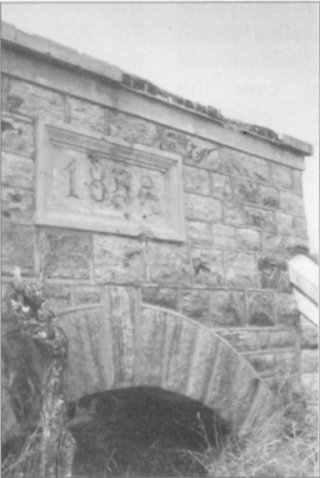

Photo 2: The rear of the portal at West Fort, showing the date '1898'.

This has now been completely vandalised.

(Photo: D Panagos).

In any event, by the time the forts had been completed, they were already obsolete. This was as a result of a major technological advance made in the field of explosives since the Turko-Russian War. The bursting charge for the Russian shells at Plevna had been gunpowder. However, in 1898, the European armies were using High Explosives (HE) in their heavy artillery shells. These came under various names such as Melinite (French) and Lyddite (British) and used the chemical, Picric Acid. The new explosive was four times more powerful than gunpowder and even more powerful than TNT. However, in the early shells, it was not always possible to achieve complete detonation, in which case it produced clouds of yellow/green smoke and a very bad smell. This led to some quaint accusations of the use of 'poison gas' being made against the British in the Anglo-Boer South African War (1899-1902)! However, the number of incompletely detonated shells from Boer guns which landed in the besieged towns of Ladysmith and Kimberley indicated that the French ammunition was no better.

When the British Army approached Pretoria at Wierda Bridge (Six Mile Spruit) on 4 June 1900, the Royal Artillery and the Royal Garrison Artillery had brought along naval 4,7inch guns and heavy howitzers firing Lyddite HE. In addition to two 5-inch howitzers and a battery of 6-inch howitzers with the VII Division, Roberts' siege train had included two massive 9,4 inch howitzers. These were made by Skoda and were sent, post haste, through Trieste to Gibraltar where they were transhipped for delivery to Cape Town. It is evident that the Pretoria forts would not have been able to withstand a bombardment by these guns using HE shells. This was an opinion confidently expressed by the American military observer, Capt Carl Reichmann. Therefore, although one of the Long Toms had been replaced in a fort, even this was withdrawn, to the mystification of the burghers and members of the commandos retreating through Pretoria.

Forts Klapperkop and Schanskop covered the approaches to Pretoria from the south, while Fort Wonderboompoort faced north. The French fort at Daspoortrand was entirely different to the other three, because it served a different purpose, in that it actually faced both south and north. It had been designed to have three guns on the south rampart facing the road from Potchefstroom at Quaggapoort, and three guns on the north rampart facing Horns Nek and the road from Rustenburg. This explains why it had two magazines with electric hoists in order to bring up ammunition to the two separate batteries. It was like a warship with broadsides, stranded on the veld, but, like the other three forts, it was also eventually armed with a single 155mm Schneider siege gun. There were four of these in total. They are often wrongly referred to as 'Creusots' because the Schneider factory was located at a village named Le Creusot, near Paris. The forts were manned by the gunners of the Transvaal Staatsartillerie and effected the protection of Pretoria for approximately two and a half years.

Photo 3: West Fort today, as seen from the north, by air.

(Photo: Prof Ian Copley).

On the arrival of Field Marshal Lord Roberts in front of Pretoria on 4 June 1900, his artillery opened fire on Fort Schanskop, but the gunners soon realised that neither this fort nor Fort Klapperkop had any teeth. The Army's field guns had engaged targets on Gun Hill where today's No 1 Military Hospital is situated and where the Boers had placed their field artillery, while the heavy howitzers moved their sights onto Muckleneuk Hill in an effort to prevent trains from leaving Pretoria Station - without effect. A few Lyddite shells from the 5-inch howitzers landed on this hill and over the town. In the meantime, Col de Lisle with his Mounted Infantry (MI) had moved over the Schurweberg to the west of Swartkop, capturing a Boer Maxim. Here he received a delegation from Pretoria who agreed to proclaim the town an 'Open City', allowing Lord Roberts to march in the next morning, unopposed. This meeting took place at what is now a suburb of Pretoria known as Proclamation Hill.

The Royal Engineers inspected the forts and were impressed with the independent water supplies. However they noted that the ramparts required better protection for riflemen and placed corrugated iron loopholed parapets at all the forts. This consisted of a double skin of iron sheets filled with shingle. This same principle was used in the construction of the prefabricated corrugated iron blockhouses when the Blockhouse Lines were built over the length and breadth of the country from January 1901. The Engineers even added a stone parapet to the east side of Wonderboompoort Fort. Unlike the ZAR loopholes, these were fitted with steel plates. The forts were then incorporated into the Royal Engineers' defences of Pretoria and, for another two years, they were to protect the town with British garrisons. Fort Daspoortrand became known as West Fort, giving this name as well to the leper asylum at the foot of the hill. After the Peace ofVereeniging, the 16th Battery of the Royal Garrison Artillery had placed a 4,7-inch QF gun on a pivot mounting at each fort. These were removed in November of the same year.

After the War, British infantry garrisons remained in the forts. In the case of Wonderboom and West Fort, they left in 1904. However, garrisons remained in the other two up to 1912 , when most of the Imperial forces left the Union of South Africa. At Klapperkop, a bored soldier of the Royal Scots Fusiliers engraved a poor copy of the Regimental Colour design in the plaster of one of the rooms. After their departure, Klapperkop and Schanskop remained unmanned in what became the Military Reserve. However during the Second World War, Schanskop was apparently used as a radio beacon station for Swartkop Airfield and was 'manned' by members of the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). On the south-west corner, a terrace was built for a number of pre-fabricated huts for their accommodation, together with a brick ablution block. A passage was cut through the rampart for access to the fort. An extension of the road was also built around the eastern and southern sides to the hut terrace. It seems that Wonderboompoort and West Fort had become part of the town lands around 1904/5.

Mysterious destruction of Fort Wonderboompoort and West Fort

Soon after the end of the Second World War, visitors to Fort Wonderboompoort and West Fort reported that they were in ruins. Claims were made by people living in Gezina, south of Wonderboompoort, that they had heard explosions coming from the hill just prior to the Second World War and similar reports came from Pretoria North. However, there was a quarry in the Voortrekker Road Nek to the east of the fort. Today, the remains of loading platforms are still present here and modern reservoirs have been built in the quarry itself. Near Pretoria North, there is a quarry next to Bon Accord Dam which is still operating. These quarries may have been the sources of the dynamiting reports.

There are several theories as to why and how the forts were destroyed, suggested in many documents. One is the claim that these two forts were blown up by Field Marshal Smuts during the Voortrekker Centenary celebrations of 1938, or even later, during the War, to prevent the Ossewa-Brandwag or some other anti-war organisation from occupying the forts, although what they were supposed to do with them after moving in remains uncertain. When a similar attempt was made recently at occupying Fort Schanskop, it was simply ignored! Considering the highly charged state of emotion between the parties in 1938/39, it seems unlikely that Smuts, known as 'slim Jannie', would have done something of the sort, which would only have made matters worse. Thus, the writer believes that these allegations can be dismissed out of hand.

Photo 4: West Fort, showing undamaged threads

on the wall bolts. (Photo: D Panagos).

Photo 5: West Fort, showing an example of a nut returned

to its parent bolt. (Photo: D Panagos).

Photo 6: West Fort. Decorative crenellations together with

the heaps of sand shovelled off the roofs of the bomb-proof rooms

without damage to the latter's walls. (Photo: D Panagos).

Photo 7: Fort Klapperkop,

showing interior roof construction.

(Photo: D Panagos).

A maintenance artisan who worked at the West Fort Leper Asylum before the Second World War told the writer that this fort was untouched up to 1940, when he left to go up North with the Union Defence Forces (UDF). On his return after the War, he resumed his duties at the asylum and, by then, the fort had been destroyed. This provides a reasonably good timeframe in which to base the investigation.

A careful inspection of both West Fort and Wonderboompoort Fort revealed two points of interest. Firstly, it should be noted that the rubble in the latter fort was cleared away just prior to 1989, leaving an empty shell. Inspection of the bolts set into the walls at West Fort, however, indicates no evidence that explosives were used to 'blow up' the forts. (In Photo 4, it is evident that, after the top covering of sand had been removed, the concrete platform was neatly broken up with drills and the large nuts on the bolts holding the steel beams over the bombproof rooms were then unscrewed. This permitted the removal of all the beams, none of which are present today.) One of the workmen had even carefully returned a nut to its parent bolt after removal of the beam (see Photo 5).

Secondly, the row of rooms under the rampart were topped by decorative crenellations and these can now be seen lying right below their original positions without damage to the walls of the bombproof rooms (see Photo 6.) This, together with the evidence of undamaged threads on the bolts, makes it clear that the fort was dismantled, probably using pneumatic drills, not dynamited, and the steel taken away. In the case of Fort Wonderboompoort, after the sand cover had been shovelled off, the concrete in which the steel beams had been embedded had then been broken up, allowing for the removal of the beams. Again, it is evident that this fort was dismantled using pneumatic drills. In neither case has any trace of the missing steel beams ever been found! (Photo 7 shows how the steel beams above the rooms inside Fort Klapperkop are embedded in concrete. The photograph also illustrates the relative sizes of the beams, indicating what a large amount of steel went into the construction.)

Who would want high-grade steel in such quantities? As mentioned above, it is significant that the two forts were dismantled at some point between 1940 and the end of the Second World War in 1945. It was during this period that the armaments industry of the Union of South Africa was born. In addition to thousands of armoured cars, the Union also produced 100 2-pounder antitank guns, 330 6-pounder antitank guns, and 391 3,7-inch field howitzers. According to the book, South Africa at War (Purnell, Cape Town), by H M Martin and Neil Orpen, (1979, p 48), a locally-made 3,7-inch howitzer had been displayed at the Rand Show in Johannesburg on 5 April 1940, but that it had been made from imported steel. It was only seven months later that the South African Iron and Steel Corporation, ISCOR, was able to produce 'the special steels' needed for the 3,7-inch guns.

Special steels are produced in furnaces such as an 'Open Hearth Converter' and require the use of high-grade scrap steel. The quality of the German steel from the forts would have served admirably for this purpose. Thus it would seem that the wartime Union Government had a strong motive for obtaining the beams from the forts for the production of the steel required for the manufacture of gun barrels. If this theory is proved correct, then the writer feels that the spirit of the erstwhile commandant-general of the ZAR must have been smiling in approval to see this steel eventually being turned into the field guns which he had always felt were preferable to static fortifications.

Photo 8: The suspect. This proudly South African 3,7-inch Gun-Howitzer

was presented to Field Marshal Jan Smuts and used to stand in front of his house

at Irene. (Photo: D Panagos).

The writer wishes to record his sincere appreciation to Rowena Wilkinson and Gerda Viljoen at the Library and Archives of the South African National Museum of Military History, Saxonwold,. Johannesburg, for their unfailing patience in dealing with his queries. And many thanks also to Brenda Carstens, Head Librarian, ISCOR, for her very valuable help indeed.

Select Bibliography

Ploeger, Col J, and Botha, Maj H, The Fortification of Pretoria - Fort Klapperkop: Yesterday and Today (Publication No 1, Government Printer,1968).

Wilson, H W, With the Flag to Pretoria, Vol II (Harmsworth, London, 1901).

Maurice, Sir Fred, The Official History of the War in South Africa (His Majesty's Government, Hurst and Blackett, London, 1906).

State Archives, Pretoria. Papers of the Military Governor of Pretoria - Orders of the Day.

Montgomery, Field Marshal Viscount, A History of Warfare (G Rainbird Ltd, 1968).

Martin, David, Duelling With Long Toms (D Martin, Ilford, United Kingdom,1988).

Van Vollenhoven, A C, 'Fort Daspoortrand as deel van die fortifikasieplan van Pretoria' in South African Journal of Cultural History, 1990.

Headlam, Maj Gen Sir John, The History of the Royal Artillery, from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War, Vol III (Royal Artillery Institution, Woolwich, 1940).

Brown, James Ambrose, The War of a Hundred Days (Ashanti Publishing Ltd, 1990).

Martin, H J, and Orpen, Neil, South Africa at War (Purnell, Cape Town, 1979). See p 353 for gun details.

Bethell, E H, The Blockhouse System in the South African War (Papers of the Royal Engineers, London, 1904).

Kruger, Rayne, Good-bye Dolly Gray (Cassel, London, 1959). Kruger provides detailed explanations of the introduction of the blockhouse lines, structures, life on blockhouse duties, as well as the importance of the lines.

The Years of Crisis: Record of the South African Metal Industries at war, 1939-1946.

The production of guns called for the use of ' ... particularly high-grade steels', p 13.

Steel in South Africa (Cape Times Ltd, Parow, published on the occasion of the Silver Jubilee of the South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corporation Ltd).

Various treatises on ordnance an ammunition to be found in the Library of the South African National Museum of Military History at Saxonwold, Johannesburg.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org