The South African

The South African

edited by Susanne Blendulf

SA National Museum of Military History

Introduction

Two years ago, in November 2001, the South African National Museum of Military History was honoured to receive a visit from a charming ex-servicewoman and veteran of the Second World War who had a most interesting story to tell. Jackie Moggridge (nee Dolores Theresa Sorour), who lives in the United Kingdom, agreed to take part in the Museum's oral history programme. The following is her own account of her years as a war-time ferry pilot for the Royal Air Force. In addition to her war medals, Jackie earned a commendation for valuable service in the air. Using a small pilot's notebook, she flew more than 1 500 aircraft during the war, 86 different types, in most cases solo.

To take to the skies!

Jackie Moggridge, woman pilot. (Photo: By courtesy, J Moggridge)

Jackie Moggridge was born Dolores Theresa Sorour at 136 Schoeman Street, Pretoria. She never knew her father, who had died of fever before she was born, and because her mother decided to remarry, her grandmother brought her up until she was eleven. She decided to call herself 'Jackie' after Jackie Rissik, a famous hockey player who represented South Africa in England. As a child, she recalls always having been terrified, but she was determined to conquer her fears. She would climb the huge Jacaranda tree in her front yard and pretend to be a pilot, flying the Hawker Furies or Hawker Demons which were in service with the South African Air Force at the time. By the age of fourteen, she knew that she wanted to be a pilot, and took up a correspondence aviation course offered in a flight magazine. For the princely sum of £1 a month, Jackie learned 'how to fly, knew all the engines and how to draw them before I even went up for a flip'. Her aviation dream was supported by her mother, her grandmother having passed away three years before.

Jackie first took to the skies at Baragwanath Aerodrome in Johannesburg where, for £3 per hour, she was allowed one hour's flight training a week. She first flew solo in a double-wing De Havilland Rapide, but instead of flying a circuit as instructed, she flew to Pretoria and landed there, before taking off again and returning to Johannesburg.

'That was my first solo', she smiled, 'I didn't even know navigation by then or how to use a compass!'

Her first parachute jump

Sheer determination and a lot of faith was how the young Jackie conquered her fear. Before qualifying for her pilot's licence, she rode to the Union Buildings on a newly-acquired motorcycle and, wearing her usual khaki shorts, walked into the office of Sir Pierre van Ryneveld, the first man in South Africa to do a parachute jump. She wanted his permission to become the first woman in South Africa to jump with a parachute. Amazed at the girl's audacity, van Ryneveld granted her an interview. Despite his attempts to dissuade her from undertaking the jump - she was too young, sure to break a leg and to walk with a limp for the rest of her life, as he did - she remained fixed on the idea and he gave her permission to do the jump on a particular Sunday.

It was raining heavily on the January, 1938, morning when Jackie was to do her recordbreaking parachute jump. The event had been publicised on radio and a large crowd had turned up. High above them, strapped into a parachute kindly supplied by the South African Air Force, Jackie prepared to jump. She stepped out onto the wing of the bi-plane and, being so light, was immediately blown off and somersaulted through the air. She pulled the ripcord, the parachute opened, jerking her neck, and then she seemed to be standing still in the air. Shortly before touching down, the parachute collapsed and Jackie landed hard in the middle of a polo field, breaking her ankle.

'It was like the poem The ride of the 600 and they were all heading for me on their horses and they picked me up', she explained. While she was in hospital, a parachute instructor from Cape Town came to see the 'silly girl who'd done a parachute jump without any training' and he was horrified to discover that she was 'only a child'. She had written to him before the jump, hoping for some advice, but had never received a reply!

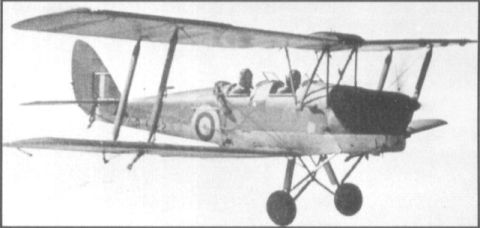

A Tiger Moth takes to the air. (Photo: by courtesy, SANMMH).

To England, to war

On 24 June 1938, Jackie Sorour left South Africa for England to undergo further pilot training at an aeronautical college. By then, she had obtained her 'A' licence and wanted to become a professional pilot. The choice open to her was either to join a flying club in South Africa, in which case it would take a long time for her to clock up the flying hours needed, or to go to an expensive professional school in England. She was still at the college, having clocked up 400 hours, when the Second World War broke out on 3 September 1939. The only woman student doing a professional pilot's course there, which entailed flying, engineering, navigation, astronavigation and so on, she was called up for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) along with the male students. She was posted to the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), but they unfortunately considered her too young to fly RAF aircraft - preferring their pilots to be in their mid-twenties - so Jackie spent the first ten months of the war on the ground, as a radar operator.

In radar

At that time, Jackie explained, 'it wasn't called radar ... it was called RDF' and it was the first line of defence against invading enemy bombers. After three weeks' training, Jackie and two other RAF women were set to work in the tiny RDF hut at Rye Station. The station was very isolated and consisted of a collection of tiny huts, 6x10ft (1,8 x 3 metres) in size. The sleeping quarters were tiny, there was no hot water and only three or four basins in which to wash, and the typical daily meal was baked beans on dry bread. 'It was really very difficult,' she recollected, 'but we were all young and we didn't notice it.' Shifts were eight hours on and eight hours off and the whole operation was shrouded in secrecy. Jackie recalls that she had to pretend to be a cook. In the hut where she worked, the operator would sit in front of a screen and, by observing lights moving across it from left to right or vice versa, she was able to distinguish between enemy aircraft and friendly aircraft, balloons protecting England, mountains, and so on. The radar machine itself was operated from another hut, and yet another served as a plotting room, where the coordinates of suspected enemy aircraft were calculated and placed on a chart. On discovering anything unusual, the radar station would phone the coordinates through to a controller, located underground at Uxbridge, London, providing the height, direction and number of approaching aircraft. Fighter aircraft would then be sent up to intercept the enemy bombers.

'But...funnily enough, the bombers always used to come over at night and of course we couldn't send any fighters up at night because the Spitfires couldn't fly at night at that time. It was very difficult. And so they just went straight through and bombed London - to destruction really ... ' Jackie said. The situation really became desperate when the Germans began to send over hundreds of bombers at a time when there were only a handful of Spitfires with which to intercept them.

'They started taking iron railings from everywhere to build these various aircraft and at that time we were building Hurricanes and Spitfires ... [which were] very good fighter[s] compared with the opposition and so we were somehow or other managing to shoot some of them down, but of course we were being bombed absolutely horrifically ... I don't know how we won the war, quite honestly.'

Jackie was on duty one night when, at 01.30, about two hundred bombers suddenly appeared on the radar screen. The controller at Uxbridge was incredulous. 'Don't be silly, Rye,' came the reply, 'It's late. You're probably half asleep. You don't know what you're doing!' When Jackie insisted that she was right, they sent up four or five Spitfires, which were all that were available, and horrific bombing ensued. Soon afterwards, the shortage of qualified pilots became critical, and on 29 July 1940, Jackie was whisked away from radar operations and seconded to the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) as a ferry pilot. It was at this time that Jackie met her husband, an engineer.

The Air Transport Auxiliary

Jackie started off flying light aircraft, and was stationed for a year at De Havilland Place in London. Here, the De Havilland brothers were testing all the new types of aircraft. 'They were flying the new Mosquito which was a marvellous aeroplane, all made of wood.' she explained, 'Very fast, it would take off and do a slow roll from the ground on one engine ... They (the brothers) were both killed eventually, they were the test pilots ... and then we went down to the south where all the factories are in the south of England near Southampton and then we started flying everything .. .' It was through this experience that Jackie developed her preference for certain aircraft types.

'In those days, we didn't really have lessons. We had a Harvard, which is an American trainer which was very noisy and we had an hour and a half on the Harvard and then we'd fly a Hurricane. We had to fly five Hurricanes before we were allowed to fly the Spitfire, because the Spitfire wasn't easy to fly ... but personally I thought it flew like a Tiger Moth, very easy and delicate - a lady's aeroplane really .. .'

Jackie flew her first Spitfire from Oxford and it was a memorable flight. 'We had to take off between all the factories and everything and it was like an explosion. You don't use full power for take-off; you only used what you called "zero-boost" in those days, which was about half the power of those aircraft ... To take off over those factories, you had to start with the left rudder on and you had to have your brakes on to the last minute because it was such a small field and then you let go and take off and shoot off. But I was alright. I was safe. I got to Turnhill Aerodrome in the north and I got out and I kissed that Spitfire on the nose as I was terrified but, as I say, I prayed hard and God flies it for me.'

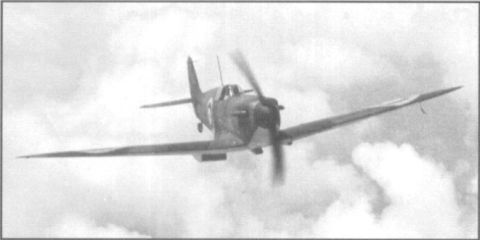

The Vickers Supermarine Spitfire fighter

(Photo: By courtesy. SANMMH) ]

Not having flown at all during her ten-months' stint as a radar operator, Jackie went for a test and made three good landings: She was accepted and fitted for a uniform and recalls having been the fifteenth woman ferry pilot to join the ATA - there were about 1 500 male pilots. Her first duty involved flying to Scotland, in formation with another four aircraft, something she had never done before. She was told to fly at the back and to keep her distance. Only the leader had a map. It was winter and in the light aircraft with open cockpits, through thick fog and snow and sleet, they headed for a destination some 450 miles (725km) away. After two hours, the aircraft needed to land for refuelling, but Jackie lost the other four in the dense cloud and fog. She landed, noticed four aircraft ahead of her, still flying, and took off again, following them and assuming that she had landed at the wrong aerodrome. The visibility was so poor that the five aircraft flew along a railway line to avoid the hills on either side. Half an hour later, Jackie landed at Prestwick, which was just a small airfield then, her fuel tank empty. It was then that she learnt that she had been following the wrong four! She returned south by train to ferry something else. As it transpired, the original four she had followed were stuck in the heavy fog for a week!

She recalled that her favourite aircraft was the Mosquito, 'which was very very fast, and later on we flew the Typhoons and then towards the end of the war we had the two jets - the Vampire jet, which was a single-engine aeroplane, and the Meteor, which was a two-seater with twin engines. Now it sounds terrible to say that they were easier to fly, but jets were so much easier to fly than, say, the Spitfire.'

Notebook flying

'People can't imagine how we flew those aeroplanes with a notebook.' Jackie smiled, recalling that before she flew her first Mosquito, she had not even sat in one. The ferry pilots were issued with a little notebook which had a page of instructions for every type of aircraft, and there were hundreds of types. For example, there were 21 different types of Spitfires, and they all needed different instructions.

'It was a nuisance,' she said, 'but, you know ... You might have a Griffin engine, or a Rolls Royce engine and they flew the opposite way. If you took off with a hard left rudder on a Griffin engine, you'd kill yourself. You had to have right rudder on the Griffin engine and on a Rolls Royce engine you had to have left rudder. .. You had to look at your notebooks - there was no way you could fly without them; the aircraft were all different.'

As a ferry pilot, Jackie was only permitted to fly during daylight hours and she was not allowed to use the radio because of the threat of enemy aircraft. Often there was no radio, because the aircraft was being flown from one place to another to have one fitted. There were no bombs, guns, navigation equipment, or crew on board. With the exception of a few large twin or four-engine aircraft, when a young air cadet would be on board to switch the fuel tanks at the back of the aircraft, the ferry pilot was expected to fly solo.

She recalled one humorous occasion, before the D-Day landings, when she had been about to take off in a big, lumbering troop carrier with a young air cadet on board. A car pulled up beside her and an RAF squadron leader asked if he could catch a flight to his base which was close to this particular aircraft's destination. Jackie told the young cadet to allow the pilot on board, and when he came up to them, he stared from one to the other and asked for the pilot. When the ATC indicated to Jackie who was sitting in her usual attire - 'an ordinary shirt and my dark trousers and no helmet' - he was incredulous and said, 'I mean the pilot flying the aircraft.' Again, the ATC pointed to Jackie and the squadron leader's disparaging response was: 'Don't tell me they've got schoolgirls flying our aeroplanes!' With only half an hour's daylight remaining, Jackie immediately went back to reading her notes in preparation for takeoff, and the squadron leader settled into the bomb-aimer's seat right in front. Once in the air, Jackie again consulted the notes to set the cruising speed and then, closer to her destination, in thick fog, she glanced briefly at the book to set the various dials, flaps and so on in anticipation of landing. The airfield, on hearing her approach, sent up a green light to indicate where she should land, and she made a fine landing .. When her passenger, impressed by her landing in spite of the poor visibility and by her ability to control the aircraft, navigate, and 'read a book' all at once, learnt that the little book bore flying instructions and that she had never flown this type of aircraft before, he went 'green' and hurried away.

Amy Johnson

Unlike most women ferry pilots in the ATA, Jackie Moggridge was young and had trained as a professional pilot. The others, she explained, were generally older and came from the wealthy upper classes of English society. They were members of recreational flying clubs and had flown their own light aircraft before the war. Amy Johnson, who had joined the ATA in her thirties, was one of these 'sports pilots'. She had made history by becoming the first woman to fly solo to Australia and Jackie held her in high regard.

'She was doing what we called "taxi" work,' Jackie said, explaining that Amy would fly an Anson, which could carry thirteen people seated on their parachutes, to a certain place to pick up ferry pilots from one aerodrome and carry them to another, where more aircraft were waiting to be ferried. Once, after Jackie had delivered an aircraft to Cardiff, Wales, Amy Johnson had arrived to pick her up and landed just as the thick sea fog came in. The return flight to England was delayed. 'She was wonderful and I was so proud to think that I was with Amy Johnson, world famous pilot, you know, record breaking pilot. And she was 33 and I was not twenty yet. .. and ... the weather was just solid on the ground for the whole weekend, so she took me all around Cardiff and treated me like a little girl and bought me chocolates and ice cream with her sweet rations. Everybody sort of knew her in Cardiff and I was very proud to be with her.' When the weather cleared, Amy flew Jackie back to her base.

Speaking about the tragic death of the famous pilot, Jackie described her as 'a very, very nice person.' In inclement weather, Amy had attempted to fly over the clouds and had been swept forty miles (64km) off course, eventually coming down in the Thames Estuary. Her body was never recovered and neither was that of a Naval officer who had seen her parachute and had jumped overboard to try to rescue her. 'Afterwards,' Jackie explained, 'We all had to train to release our parachutes if we were going over water because you just sink and that's it, you die, because you sink with the parachute.'

On perceptions

Jackie married an engineer and always felt that it was rather unfair that society tended to hold pilots in higher regard than the men who designed the magnificent aircraft they flew. The popular image of a pilot was that of a courageous, tall, experienced hero wearing wings on his chest. In contrast, Jackie was small and young and a woman and, as a result, she was often mistaken for being anything but the distinguished pilot she was. On one occasion, for example, when she was transporting a new type of aircraft, with tricycle undercarriage, for shipment to Russia, she had landed in thick fog at an airfield near the coast and, while waiting for the weather to improve so that she could complete her journey, had presented herself to the control tower. She was offered a cup of tea by the kind RAF controller working there. Soon afterwards, the commanding officer entered the control tower and, seeing her there, became incensed. 'I don't like having all these odd bods sitting in the control tower.' he berated the controller, 'You know they are not allowed! You must get rid of them!' Not wishing to cause any further trouble, Jackie quietly returned to her machine. Later, noticing the interesting new aircraft, the commanding officer asked to see the pilot and the controller explained to him that he had just had her thrown out! Needless to say, he apologised profusely to Jackie, treating her to tea and lunch, but she felt that nobody deserved to be treated so badly. 'You know, just because you're a pilot doesn't make you more important than anyone else. I don't think they are, but that's the sort of thing we had to put up with.' Given these perceptions, and the attitude of male pilots towards them, it was often not easy for women pilots to acquire the recognition they deserved.

Jackie Moggridge poses beside the Spitfire

during her November 2001 visit to the South African

National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg.

(Photo: SANMMH).

Jackie Moggridge's post-war career

The war had disrupted Jackie's ambition to become a professional pilot, so, after the war, as a wife and mother, she redid her examinations, qualified, and joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. She flew professionally for 46 years. The highlight of her flying career came in 1953, when she and five other women pilots were finally awarded their RAF wings. This gave her an opportunity to break the sound barrier in a North American Sabre jet, possibly the first to do so in Britain, although the event was shrouded in secrecy. She believes that she was selected to fly the new jet because it was a 'first woman [in England] sort of thing through the sound barrier', much to the consternation of the male pilots. Another Jackie, Jackie Oriel, a French woman test pilot, had been the first woman to break the sound barrier and after that, 'because we were only the second in England, it didn't count that so we weren't allowed to tell anybody.' Sadly, in 1954, Jackie had to end her service with the RAF because they no longer required the services of women pilots, and Jackie then began to ferry various aircraft to the Middle East and to Burma and India and the Far East. In 1957, her book, The Woman Pilot, was published; in view of her safety, a quarter of the book had to be cut out. In 1994, she enjoyed a reunion with her old war-time companion, when she flew in an old Spitfire which had her name recorded on its log as the first person to fly it. This flight was undertaken as part of the D-Day commemorations and was a well publicised event.

A great future for women pilots

Just a month or so before Jackie Moggridge visited the Museum to relate her war experiences to us, she had attended the Royal International Aircraft Tattoo, an air show in the United Kingdom, where, as a special guest, she had met, amongst others, eleven current South African women military pilots, including one black woman 'very sweet girls, all about twenty-two and very nice and slim and pretty. I was very proud of them'. A memorable photograph was taken of Jackie, in uniform and in a wheelchair because her leg was in plaster at the time, posing with women pilots from all over the world in front of a Harrier jet. She was particularly delighted to meet the girls from Pretoria, the place where her adventure had begun so many years before.

I've just enjoyed reading your article on Jackie Moggridge but a couple of things jumped out as 'not quite right'.

In the paragraph relating Jackie Moggridge's post-war career there is a mention of a French aviatrix - Jackie Oriel. This, I am sure is a reference to Madame Jacqueline Auriol - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacqueline_Auriol

In the para entitled The Air Transport Auxiliary there is mention that Jackie was 'stationed for a year at De Havilland Place in London'. I have no idea what this means but I suspect it means that she was stationed at the de Havilland factory north of London (actually at Hatfield) where the Mosquito was designed and constructed. The company was headed by its founder Geoffrey de Havilland (later Sir Geoffrey); his two sons, Peter and Geoffrey Junior ('the de Havilland brothers' referred to in the article) were sadly both killed test-flying aircraft manufactured by their father's company.

Hope you don't mind my mentioning these points. I'm a retired 12000 hour airline pilot with a great interest in all things aeronautical (and I worked briefly for British Aerospace Hatfield, the former de Havilland site, in the 1980s.

Regards

Ian Roberts

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org