The South African

The South African

By Rob Burrett, Zimbabwe

Once the Boers had realised that their flight from Rhodesian territory had been for no reason, they again, on 4 November 1899, took possession of the two captured positions of Bryce's Store and Rhodes' Drift. AssistantGeneral H C J van Rensburg, in an uncharacteristic mood, then informed Pretoria that he intended to attack Fort Tuli the next day, thereafter to raid deep into Rhodesia and destroy the rail links. Nothing came of this, however; he did not have the military nerve, while Pretoria subsequently rejected his plan, suggesting that it would be a waste of resources as the real dangers to the Transvaal Republic lay to the south.

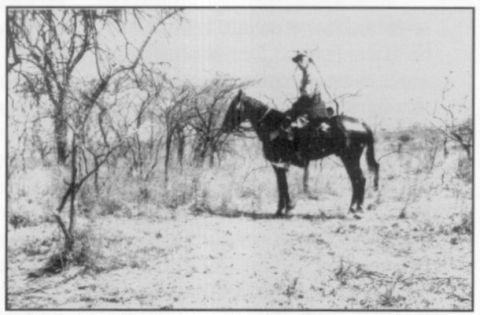

After the Boer successes, Lieutenant-Colonel H C a Plumer determined that it would be best to concentrate his Imperial forces at Fort Tuli. As a result, the Limpopo drifts were abandoned and instead the Rhodesians opted for a regular series of patrols that were sent out from Fort Tuli on a daily basis. Most were routine reconnaissance, focussing on the enemy's positions at Bryce's Store, but there were a few skirmishes. One of the leaders was Captain A W Jarvis, in command of 'D' Troop, who wrote to his mother detailed accounts of the often tedious work: 'Day is up 3.30am, saddle 4am, march 4.30am and back 8.30pm ... Our aim is to work up to Boer positions as close as I can ... I have formed a good scouting section in my squad of 12 picked men (6 at a time). We work our way through the bush as far as I think safe with the troop. Leaving others in the troop in support, I go forward myself with 6 men and leave the troop in position to cover ... When I and my scouts are pretty close we get off our horses and crawl on through the bush with 1 at the most 2 men to get to a place where we can spy on the enemy, digging entrenchments and making forts, as well as getting guns and other engines of destruction in place.' (Jarvis, 11 November 1899).

Capt A W Jarvis, commanding 'D' Troop, Rhodesian Regiment,

somewhere near Fort Tuli, 1899 (Photo: By courtesy, National Archives, Zimbabwe).

The Rhodesians found that the Boers had obviously decided that Bryce's Store was to be an important forward position. It was strongly fortified and was occupied by a large force supported by two Maxims and a field gun. These were individually placed on the three kopjes surrounding Bryce's Store. (Please note that the modern-day kopje photograph which appeared on p126, Military History Journal, Vol 12 No 4, December 2002, in Part 2 of this series of articles, refers to one of these near Bryce's Store, and was erroneously placed in the earlier issue to illustrate the kopje near Pont's Drift. My apologies - Editor).

In the light of his small numbers and set-backs, Plumer decided to strengthen his 'Native Forces'. Their principle role was to be cross-border reconnaissance, although these troops were increasingly drawn into active combat in the final days of the war. About thirty specially selected Matabele scouts were drawn from the Native Department under the command of Mr Posselt. They joined and took command of an existing 'Tuli Border Guard', who were Africans drawn from the British South Africa Police (BSAP), from the local Native Commissioner's men, and from Mpofu's people. The last named were Venda refugees from the Transvaal who had a particular grudge against the Boers, having been defeated in rebellion as late as 1898. The whole 'Native Unit' was placed under the control of R Trevor of the BSAP.

Meanwhile, along the border, action had moved a considerable distance downstream on the Limpopo. Near Malala Drift (refer to Map 2, Part One: The Prelude, Military History Journal, Vol 12 No 3, p78) a party of about 300 Boers crossed into Rhodesia on 1 November 1899 and had raided several local villages, taking cattle as well as a wagon from a resident English trader called Roxby. The Boers had tried to incite the local people to rebel against the English, but they declined and, in the ensuing scuffle, six Africans were killed. On 6 November, the majority of these Boers left the Drift, but thirty were left to maintain watch. The administration in Salisbury (now Harare) was unable to react at the time as it was a fairly remote place and they were hard pressed for manpower.

It was now extremely hot and dry in the Limpopo Valley and both sides crept around each other, but there was little action between them. This was soon to change. A party of 78 Boers with fifteen wagons had been sighted at Baines' Drift heading northward. This was Commandant-General FA Grobler, commander of the wider northern front. He had spent most of the war further to the south-west with the Waterberg Commando. His force proved very reluctant to take action and Grobler had problems with insubordinate Waterberg commandants, a number of whom were replaced and others unsuccessfully threatened by the High Command in Pretoria. The tying down of Grobler in the south-west effectively deprived the Zoutpansberg Commando of any real military leadership; it probably won the stand-off for the Rhodesians.

This column arrived at Hendriksdal on 12 November 1899. Grobler gave serious consideration to van Rensburg's plan to attack Rhodesia, again contacting the High Command in Pretoria with details of a full-scale invasion. However, this was not to be. A rapid response from the State Secretary rejected all plans. Pretoria felt that the men and artillery were needlessly tied up and could used to better effect elsewhere. The small Rhodesian force was no real threat to State security, certainly nothing like the contemporary build-up of British forces in the Cape and Natal.

Accordingly, the North-West Commando was split. A small detachment was left to guard the entire length of the Limpopo. The remaining and larger proportion of the initial force, including almost all of the commanders, was recalled to Pretoria; there, they were again split into two groups, the larger section, under Grobler, being sent to Modder River, and one hundred men under van Rensburg going to Colenso, where they participated in the historic defeat of the Natal Field Force under General R Buller in actions incompatible with their earlier efforts along the northwestern frontier. The burghers remaining on the north-western front were divided into three main camps, each of three hundred men. The nearest of these posts to the Tuli area was the one at Brak River Store on the western end of the Soutpansberg.

On 13 November, a force of Boers again crossed the Limpopo at Malala Drift. They sent out calls to all the African chiefs as far as the Lundi River (now Runde River) to come to their camp to discuss matters, presumably insurrection. A negative response from some of those nearby drew a sharp reaction. Several villages were attacked and their cattle were confiscated. These Boers remained active in this area until early December when they withdrew after one of the local chiefs, Sewass, captured four Boer wives and held them ransom, demanding the return of his cattle.

Meanwhile, heavy rains began to fall in the area and soon most of the rivers near Fort Tuli were impassable. The last substantive action in this arena took place on 18 November 1899. A reconnoitring party under Captain Jarvis was ambushed on the Rhodes' Drift road, about 20km from Fort Tuli in the direction of Bryce's Store. Here is Jarvis's own letter to his mother describing the incident:

' ... our patrolling in this terribly difficult country still continues and we have been wondering amongst ourselves often lately whose fate it will be to get chopped. The country lends itself so especially to traps and ambushes of every description. I was nearly the victim ... they nearly had my patrol out in the early morning by lying in a donga in the bush in a frightfully difficult place, where the squad patrols from here [Fort Tuli] MUST pass to get a view of THEIR position. I luckily posted the men with me on a kopje just before I came to this place and was going forward from there with only five of my scouts. We had just got there when a lucky incident just showed us a HAT move on a ridge to our right. We saw nothing else but just as we thought to move a hat bobbed down below the sky line. We laid up in the bush, spied with glasses three men in the rocks & bush. I sent four men to reconnoitre the sides to see numbers. We moved 800 yards [730m]. The Boers realised that something was up as they spotted my scouts. Others joined them. One Boer went to the hill and waved his hat [signal]. Seeing me and company were being surrounded, we went back into the donga and moved out. The shooting now started. We had to go over the kopje where the troop was. We had to scramble up and over in the open with our horses. Shot at heavily, it rained Mauser bullets. All the troop horses stampeded in fright, so I had to get all the men together to hold our position.

Luckily, [the] horses [were] captured by another troop six miles off. They came at once. We retreated. Three men killed, lost three horses. Recovered bodies of two of the poor fellows and of course not certain if the third WAS killed, but fear so.' (Jarvis 19 November 1899).

The dead were Troopers G Cook and G H Perrett, while Trooper M Barthropp was captured, being released by British troops in Pretoria with the other POWs in June 1900.

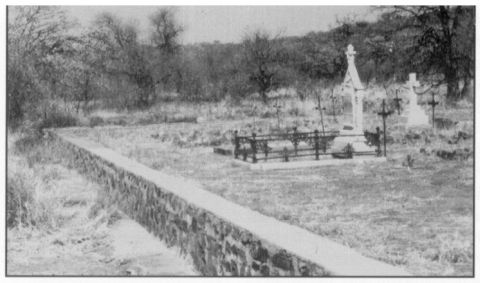

View of the European cemetery at Fort Tuli, showing the

Anglo-Boer War graves (Photo: By courtesy, R S Burrett).

About this time, the Rhodesian authorities became very concerned about reports of imminent treason amongst the resident Afrikaners in south-west Rhodesia. Local spies reported that fifty to sixty 'Rhodesian Dutch' in the Mangwe area had stockpiled arms and would assist their Transvaal brethren in simultaneous attacks on Fort Tuli and Palapye, then moving on to Bulawayo, coming up the Semokwe route via Mangwe. A prominent Mangwe rancher, J C van Rooyen, was reported to have agreed to guide Grobler with eight hundred men by this back route. This was supposedly planned for 3 December 1899. It was therefore decided that the Mangwe area must be reinforced with a strong BSAP presence, that all the 'Dutch' would be disarmed, and that Martial Law would be declared in the southern parts of the country. If there was ever a Boer rebellion planned, these actions effectively thwarted it, although it remained a security concern for the Rhodesian authorities.

Meanwhile, the monotonous patrolling from Fort Tuli continued. I quote another of Jarvis's letters: ' ... no collision since scrap last Saturday. The same game of hunting and stalking each other. Now march out at 2.30 am, back at 8 pm ... We have tea & bullybeef and bullybeef & tea, breakfast, lunch and dinner ... You never saw anything like the number of beetles, scorpions and creepy things generally that there are about this place. Men worried about bathing in the river because of crocodiles.' (Jarvis, 24 November 1899).

On 26 November, a Rhodesian patrol found that the Boer fortifications at Bryce's Store had unexpectedly been deserted. The Rhodesians were wary of a trap and numerous well-armed patrols were sent throughout the area. However, there were no Boers anywhere and the drifts were abandoned. Even the main Boer camp at Hendriksdal in the Transvaal was found to be deserted. Plumer sensed victory and began to make plans to leave Fort Tuli and move, with a larger part of his force, to undertake operations further south in Bechuanaland. Baden-Powell was still besieged in Mafeking.

Plumer first had to ensure that the retreat was real and, accordingly, he planned a six-day patrol of a hundred and fifty men deep into the Transvaal. Sometimes referred to as 'Plumer's Flying Column', they left Fort Tuli on 1 December 1899. After thoroughly checking the vicinities of Bryce's Store, Rhodes' and Pont Drifts, the column crossed the Limpopo into Transvaal territory on 3 December at the junction of the Limpopo and Macloutsie rivers. They then rode through the veld for eighteen hours to a point on the coach road 80km north of Pietersburg. However, the extremely hot and dry conditions, made worse by a scarcity of surface water and grazing for the weakening horses, meant that this reconnaissance had to be terminated prematurely and the party moved back to Rhodes' Drift. During this patrol, however, no Boers had been seen, and it seemed that they had abandoned the area. A second patrol to Pietersburg itself was abandoned as heavy rains caused the Limpopo to flood, denying the Rhodesians access. A new raft was built at Pont Drift, but this only allowed small groups of men to patrol immediately south of the Limpopo to see if any Boers were returning. Otherwise, life at Fort Tuli became routine and uneventful for both men and officers - 'endless tea and bully' (Jarvis, 10 December 1899).

Plumer then deployed Mpofu's men (Venda refugees from the Transvaal) to undertake patrols deep into the heart of the northern Transvaal. They were commanded by Rhodesian officers, lieutenants Taylor and Trevor. All patrols confirmed an almost complete Boer abandonment of the area. As a result, Plumer transmitted his intentions to the authorities in Bulawayo that he would to leave Fort Tuli, cutting across country to reach the railway line in Bechuanaland. A hundred and thirty men would be left on guard duty at Fort Tuli and Macloutsie.

On 27 December 1899, reports received suggested that a new party of Boers had laagered 6km south of the Brak River Store. At the same time, Taylor, Trevor and their black scouts were reconnoitring towards Magatos Mountain, where they clashed with a large party of black scouts on the Boer side. In the encounter, the Rhodesians lost three men, Malamitzi and two of his followers. These developments worried the Rhodesian authorities, who concluded that there would be a renewed attack on their southern flank. Plumer was less disturbed, although he did acquiesce to leaving more men and the heavy artillery at Fort Tuli, a decision he would later regret when he came up against strong Boer resistance further to the south.

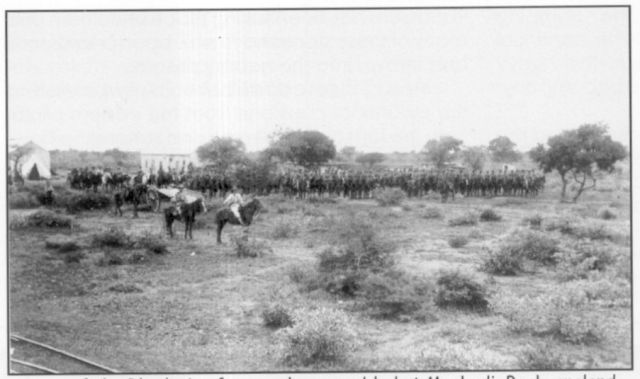

Some of the Rhodesian forces who assembled at Mochudi, Bechuanaland,

January 1900 (Photo: By courtesy, Natio~al Archives, Zimbabwe).

The move began on 28 December, and over the next few days, several troops of men and wagons marched to the south-west to reach Macloutsie. This was a particularly heavy trek, exacerbated by the hot, dry conditions and lack of water and grazing. From there, they pressed on to Palapye and thereafter travelled by train southward to the '1 016th Mile Post' along the railway just north of Mochudi. There, full strength was regained by 11 January 1900 and the action passed from Fort Tuli and the Limpopo Valley. Plumer's Rhodesia Regiment, the British South Africa Police, the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers, and several newly-arrived Imperial Troops formed a joint force that moved down the railway towards Mafeking. There were several major clashes along the way, most notably at Crocodile Pools and Ramathlabana, but those are other stories (cf Hickman, 1970; Millington & Burrett, 2000).

Defences at Fort Tuli were weak. There were few men, with even fewer horses, preventing effective border patrols. In fact, Plumer had very little faith in those of his force remaining: ' ... most of the men of the Rhodesia Regiment left at Tuli were chosen as the least efficient of Colonel Plumer's force' (RC). They initially re-established a post at Rhodes' Drift but this was abandoned by the end of January, as the Limpopo had again come down in flood, smashing their newly-built pont. These men were then posted to the supposedly healthier, higher ground at Bryce's Store.

On 9 January 1900, reports were received that a substantial number of Boers were trekking towards Mozambique and into what is today the lowveld in south-east Zimbabwe. Unlike earlier incidents, these were whole family groups together with stock and servants. Undoubtedly they were Boer civilians fleeing the British advances in southern and central Transvaal. Again, a lack of manpower prevented the Rhodesian authorities from doing anything, but with the Limpopo in full flow it was felt that the natural defences of the southern border were suffice for the time.

By early March 1900, however, the river was down and there were reports of renewed cross-border raiding by Boers said to be short of food. A party of about sixty to seventy Boers was said to be encamped opposite Malala Drift and they were again looting Matibi's and Marunguse's cattle. A strong party of BSAP, assisted by the Mashonaland Native Police, was ordered to proceed to the border, but this was later counter-ordered and they were re-deployed to Bechuanaland to assist Plumer's column that was taking a battering.

The Rhodesian authorities was still extremely anxious about the safety of its southern border, especially as the guerrilla phase of the war commenced, with isolated attacks on strategic targets, cattle raiding, reprisals and counterattacks etc. The Fort Tuli force was clearly inadequate and thus a squad of newly-arrived Australian Bushmen en route to Mafeking from Beira were rerouted there (cf Hickman, 1975; Burrett, 2000). Lord Roberts had several reasons for this decision - to defend Rhodesia from guerrilla attack; to cut off any Boer retreat northward as British troops stormed the Transvaal from the south; to win over local black sympathisers in the Soutpansberg; and to go on the offensive towards Pietersburg, the main Boer centre in the northern Transvaal. To achieve the latter objective, Maj Gen F Carrington, commander of the Rhodesian Field Force of which these men were part, was ordered to send 1 200 men across the Limpopo drifts to reach (and capture) Pietersburg by 25 July 1900. While they were marching, however, Roberts counterordered that they were to be re-deployed to Mafeking. Such was the confused, often directionless, state of affairs at the time.

On 16 August, the commander of Fort Tuli reported that several armed Boers had been sighted scouting the drifts with the obvious intention of crossing. They were part of a large, mixed party of men, women and children, who had arrived from Pietersburg with a Maxim and two field guns and were camped at Magatos Mountain. Obviously, these were displaced people seeking the safety of the mountains as British forces overran their Republic, and may have been looking for food or even an escape route northward.

The Rhodesian authorities viewed this development as threatening and it was decided that the forces along the Limpopo now had be increased. On 24 August, a hundred men of the Imperial Yeomanry, a section of Carrington's Rhodesian Field Force then stationed at Fort Victoria, was thus ordered to Fort Tuli for Rhodesia's defence. This, again, was promptly counter-ordered by 'higher authorities' on 25 August, only to be reordered on 30 August 1900 after substantial pressure from the Rhodesians. This time, the force was to be joined by remnants of New Zealand and Australian forces then in the country.

In the meantime, Boer crossings at Main, Massibi's and Middle drifts become regular events, although no action is recorded. For those on the border, it became merely a game of watching and waiting. The Imperial Yeomanry and others finally arrived at Fort Tuli in late September. However, their arrival brought enteric fever and they were effectively quarantined on arrival at Fort Tuli. The living conditions were worsened by the fact that supplies were running very low and the men were placed on half rations, while their horses had no additional fodder and had to make do on the natural grazing in the area. Small numbers were allowed to occupy Bryce's Store and Pont Drift and a limited number of patrols reconnoitred deep into the Transvaal as far as the Brak River Store. Otherwise, the men were detained in the sick lines or put through endless training sessions, the futility of which was later questioned by several of the participants. After Carrington's delayed arrival, he took one large troop into the Transvaal on 26 October. They patrolled for over a week, negotiating allegiance with various black tribes they encountered.

On 10 November, orders were again received from Lord Roberts that all these troops were to move to the Cape. This was again countermanded, requiring only the Imperial Yeomanry to be reassigned, while the Australians and the New Zealanders would move to Rhodes' Drift with the view of marching on Pietersburg. Soon after, the orders were again changed. Almost the entire force would move to Bechuanaland with only a few being left behind to add to the existing Fort Tuli guard. The military camp had recently been relocated to the east bank of the Shashe River as floods were threatening to cut off the old forts on the west bank from communications with the rest of Rhodesia.

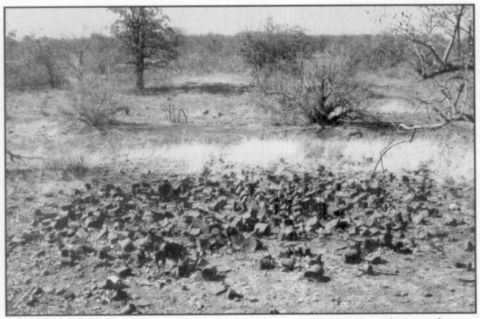

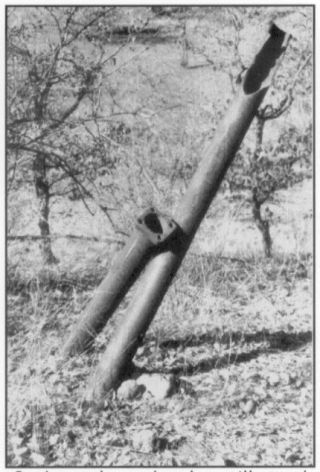

This rubbish dump, where the dry semi-desert conditions have preserved tins,

bottles and other relics, is the last major remnant of the Rhodesian and Imperial forces

at Fort Tuli during the war. (Photo: By courtesy, R S Burrett).

Broken telegraph poles still stand at the end of the line

from Rhodes' Drift to the 1899 fort at Fort Tuli.

(Photo: RS Burrett).

Thereafter, official interest and militarisation of Fort Tuli falls away. Clearly nothing came of the supposed Boer invasion, if it really was one and not simply a movement of refugees. Fort Tuli and its neighbourhood faded entirely from the scene, out of Rhodesian and Botswana history. All that remained, for a while, were a small rural Police Station and a Native Department presence, much the same as anywhere else.

SOURCES

Only direct quotations relevant to this section are cited here. For fuller details, readers are advised to refer to the original manuscripts by the same author, mentioned in earlier articles in this series.

Burrett, R S, 'Rhodesian Field Force (Anglo-South African War) graves in Zimbabwe, with particular reference to Marondera' in Heritage of Zimbabwe, No19, 2000, pp22-45.

Hickman A S, Rhodesia Served the Queen, Vol 1 (Rhodesian Army, Salisbury,1970).

Hickman A S, Rhodesia Served the Queen, Vol 2 (Rhodesian Army, Salisbury,1975).

Jarvis, A W, Correspondence to his mother. Historical Manuscripts. National Archives of Zimbabwe. JA 4/1/2.

Millington P & Burrett, R S, 'Action at Crocodile Pools during the Anglo-South African War and death of Captain Sampson French' in Botswana Notes & Records, Vol 32, 2000.

RC = Resident Commissioner telegrams to Administrator. Public Archives Pre1923. National Archives of Zimbabwe. RC 7/2/1.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org