The South African

The South African

By Dr M J Thomas

Researcher, Port Cities Project (NOF)

National Maritime Museum, London, UK

With his crew, Hauptsturmfuhrer Michael Wittmann of the

Leibstandarte inspects the 'kill rings' on the barrel of their Tiger.

Wittmann was later killed in action against the Allies in Normandy in 1944.

(Photo: Author's Collection).

In our previous discussion, see Military History Journal (incorporating Museum Review), Vol 12 No 5, June 2003, pp 176-83, we documented how a potent mixture of politics and military training produced a highly effective force that was ready to carry out the Fuhrer's aims. A new quality emerged, called 'Harte'. It meant many things-toughness in battle, fearlessness, ruthlessness in the execution of orders and dedication to victory at all costs. It also meant contempt for the enemy, callousness to prisoners and brutality to all who stood in the way. The SS proved to be not just soldiers, but fighters who fought as often as not for the sake of fighting.

An American officer who came up against the Leibstandarte in the Ardennes in 1944 reported: 'These men revealed a form of fighting that is new to me. They are obviously soldiers, but they fight as if military ways were of no consequence. They actually seem to enjoy combat.' An SS Hauptsturmfuhrer recalling the 'sheer beauty' of the fighting in Russia in 1942, stated 'it was well worth the dreadful suffering, after a time we got to the point where we were concerned not for ourselves, or even Germany, but lived entirely for the next clash.' (Sayer & Bothing, 1989, p18). The fighting spirit of the Waffen SS can be put down to ideology, comradeship and, in the case of the foreign volunteers, to the fact that they could not surrender, because that normally meant the firing squad. Thus, the French 33rd SS Division Charlemagne fought to the last in the defence of Berlin, where it was almost wiped out (R Landwehr, 1989, pp 167-73).

The Waffen SS was clearly a formidable opponent. Its successes in the field were frequent. The Leibstandarte seized the first bridgehead over the Dnieper, broke through the Soviet defences at the Crimea at Perekop and stormed Taganrog and Rostov. The 5th SS Viking Division pursued the Russians to the Sea of Azov. Das Reich captured Belgrade in 1941 and later broke through the Moscow defences and came within 50km of the Kremlin.

In defence, the SS was equally solid. When the Soviets cut off the Totenkopf and five army divisions at Demyansk in February 1942, Eicke's division led the defence for several months before spearheading the breakthrough to freedom (Sydnor, 1989, p214-25). In December 1943, the Red Army broke through the German lines in the Ukraine and surrounded 75 000 troops at Cherkassy. Despite being surrounded by two Soviet Army groups, Viking led the breakout to the west. The division, however, had practically ceased to exist, losing nearly 20 000 men. On these occasions, at Demyansk and Cherkassy, the Waffen SS had prevented another potential Stalingrad. In Normandy in 1944, nineteen German divisions were trapped in the Falaise Pocket. They escaped, thanks to the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, which kept open a corridor until most of the units had escaped. The cost was enormous, only 300 men surviving from 21 000 (CW Luther, 1987, pp 220-31 ).

Wherever the enemy breached the lines, orders went out for the Waffen SS. They became the Fuhrer's fire brigade, always being sent to the areas of the front that were in crisis or where a breakthrough was required. The 1st SS Panzer Corps was rushed to Kharkov in early 1943 to stem the Soviet advance. They succeeded in doing so and, by the end of March, had actually retaken the city. Hitler was so impressed that he declared the Corps to be 'worth twenty Italian divisions' (Hitler's Table Talk, 5 April 1942, pp 402-3, cited in Reitlinger, 1981, p 156).

Both friend and foe agreed that the armed SS possessed fighting qualities equalled by few. General von Mackensen of 3rd Panzer Corps extolled the Leibstandarte in a letter to Himmler for its 'discipline, refreshing energy and unshakeable steadfastness, a real elite unit'. The Russians held a similar view. Major General Artemko of the 27th Army Corps, when captured in 1941, stated to his interrogators that 'his men breathed a sigh of relief when the Viking Division was withdrawn from the line and replaced by a regular army unit' (Mackensen to Himmler, 20 December 1941 and Heydrich to Himmler, 6 November 1941, RFSS Microfilm 108, cited in Hahne, 1969, p 467). Impressive as these achievements were, the Waffen SS never succeeded in altering the outcome of the major battles of the war - like Stalingrad, Kursk or Normandy - their successes were all at a local level.

Was the Waffen SS a more formidable force than the Wehrmacht beside which it fought? It is certainly true that there were only a handful of army divisions, such as Panzer Lehr and the Grossdeutschland, which could boast a combat record that equalled or surpassed that of the Leibstandarte, Das Reich or Viking. It has often been stressed that the elite Waffen SS Panzer divisions fought so well partly due to the fact that they received better quality and, on occasion, more equipment than their army counterparts (see, for example, Keegan, 1970, p 144). This argument ignores the fact that the Wehrmacht had fully fledged Panzer divisions before the SS. Only the 1 st, 2nd, 3rd and 5th SS Divisions were made up to Panzer divisions by the end of 1943. The 'elite' SS Panzer divisions were, however, substantially larger than those from the Wehrmacht towards the end of the war. By 1944, all Panzer divisions contained an armoured regiment of two battalions, one equipped with Mark IV tanks, the other with Panthers. Army Panzer divisions also contained two infantry regiments of two battalions, but SS divisions mustered six infantry battalions. The average Panzer division went into the battle of Normandy, for example, with almost 15 000 men at full strength, while SS divisions had up to 20 000 troops (M Hastings, 1984, p 349).

To what extent this extra firepower accounted for the fighting prowess of the SS divisions is unclear. The allegation that the SS units received better equipment is not convincing. When the Leibstandarte received the new Panzer Mark IVs with 75mm guns, and a number of self-propelled guns, in 1942, Panzer Lehr and Grossdeutschland received similar amounts of identical equipment (Theile, 1999, p 224). The Waffen SS divisions which received the best equipment were a minority, perhaps seven out of a force of thirty. Only the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 9th, 10th and 12th SS divisions were fully fledged Panzer divisions by 1945. The next best equipped were the Panzer Grenadier divisions, consisting of a combination of tanks and infantry. These were the 4th, 11th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 25th, 28th and 38th divisions. By no means were all of these units well-equipped and at full strength throughout the war.

The majority of the Panzer Grenadier units that grew to divisional size were never fully mechanized, and many did not always receive their full allocation of personnel. There were also three cavalry divisions and six mountain divisions. The rest were regular infantry units of varying quality. The majority of these never reached full divisional status, ranging in strength from battalion to regiment size. Less than 30 per cent of SS divisions were equipped for modern mobile warfare, which tends to erode the popular perception of the Waffen SS as a well-equipped and fully motorised Panzer force. This only applied to a handful of units (Theile, 1999, p 39).

The exploits of the 'elite' SS Panzer divisions have formed the reputation of the Waffen SS as a whole. The reality is rather different. Wegner's analysis of SS men who won the Knight's Cross reveals that the classical units like the Leibstandarte, Das Reich, Totenkopf and Viking received 55 per cent of all Knight's Crosses awarded to the Waffen SS. If one adds eight other German, West European or Scandinavian divisions, the figure rises to 84 per cent, demonstrating that less than a third of SS units earned nearly ninety per cent of all crosses (Wegner, 1990, p 312). It is evident that the 'Volksdeutsche' and Eastern divisions were of little value.

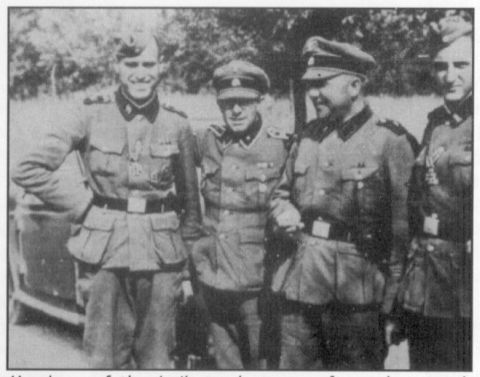

Members of the Leibstandarte pose for a photograph

during an awards' ceremony after the French campaign, 1940.

(Photo, Angelray Books).

The majority of the SS divisions performed badly from the outset. The 13th SS Bosnian Handschar Division operated at a satisfactory level fighting against partisans when it first entered the field in early 1943, but losses and declining morale had eroded the unit by the autumn of that year. When the division was first exposed to the Russians in 1944, it disintegrated (G Lepre, 1999, pp 89, 145). It was not unusual for the 'Volksdeutsche' and Eastern divisions to fail completely in battle. In January 1945, Himmler informed a subordinate that a regiment from the ethnic German 17th SS Gotz van Berlichingen Division had 'run away on contact with the enemy' (Wegner, 1990, P 312). Cases such as these have been overshadowed by the heroic reputation of a minority of SS divisions, most of which could trace their origins back to the pre-war SS, again emphasising the importance of the men who were trained before 1939 and who made up the leadership cadres of the early divisions.

The elite Waffen SS units suffered high casualty rates. There were repeated complaints from army commanders, who accused SS officers of wasting men. By mid-November 1941, five months into the invasion of Russia, Das Reich had lost 60 per cent of its combat strength, including 40 per cent of its officers (R Butler, 1989, p131). By the end of 1943, 150 000 Waffen SS troops were dead, wounded or missing. Such losses helped to establish the reputation of the Waffen SS as a force that fought to the last, but had a serious effect on the long-term future of many units. The shortage of leaders often damaged operational efficiency.

By 1944, the 12th SS Panzer Division did not have enough experienced officers to lead it. As a result, a core of 500 officers were trained from scratch in four months, whereas the early SS units had been led by highly trained personnel from Bad Tolz. Although the new officers were brave and fanatical, their lack of training is reflected in the fact that the division was almost wiped out on its first mission in Normandy (Wegner, 1990, p 322).

It is also worth stressing that the stringent selection process that was maintained in the elite divisions during the early part of the war meant that men who could have served as NCOs and junior officers in other units, served as privates in the best SS units. Germany, facing so many enemies, could not afford such wasteful misuse of men and material. It might have been better to have utilised such men in regular army formations, thus ensuring that they received proper replacements and qualified leaders, rather than concentrating these resources in a handful of formations to the disadvantage of the army in general.

The expansion of the Waffen SS led it to introduce conscription. Thus, in one way at least, the armed SS was indeed like the army. It appears that about a third of the total number of men joining the Waffen SS were conscripts or compulsory transferees, and that the proportion of such individuals was higher at the end of the war than at the beginning. By the final months of the conflict some 40 000 Luftwaffe and 5 000 Navy personnel had been transferred to the Waffen SS (Theile, 1999, P 38).

The high losses sustained in Russia also led to a decline in volunteers, put off as they were by high casualty rates. Conscription and compulsory transfers undermined the ideological core of the Waffen SS and may have affected its combat effectiveness. The volunteer in the vanguard of Nazism was a key pillar in Himmler's concept of political soldiery. The achievements of Das Reich and the Leibstandarte were largely owing to their highly motivated volunteers. Reluctant draftees would not fight as hard as the true believers. There were several cases of young party members refusing to join the Waffen SS, expressing a wish to fulfil their military service in the army. Many were threatened with expulsion from the NSDAP, hardly the calibre of recruits required for a Nazi vanguard.

War-time losses, and Himmler's desire to field a larger force, also led to the inclusion of foreign peoples into the Waffen SS as the use of German recruits was blocked by OKH. At first these were 'Aryan' Scandinavians and Dutchmen. Recruitment was initially slow, and by June 1941 only 3 000 volunteers had come forward (M P Gingerich, 1997, pp 815-30). With the invasion of the Soviet Union, however, the numbers grew rapidly as men were attracted to the anti-Bolshevik crusade in the east. As war progressed and Germany was pushed back on all fronts, Himmler could stretch his principles far enough to include the peoples of the Baltic, Ukraine, Russia and the Balkans who had earlier been classified as 'sub-human'. The irony of Slavic volunteers fighting for nordic racial supremacy was quietly ignored by the Reichsfuhrer. Many of these units performed poorly and contributed little to the combat reputation of the armed SS.

Viking Division grenadiers aboard a Sdkfz 221

four-wheeled armoured car in Russia, late 1941.

(Photo: Angelray Books).

'Normal Soldiers'?

It has been suggested that as it expanded in the latter years of the war, the Waffen SS grew to become more like the army beside which it fought. During the second half of the war, every third SS general and every fifth colonel had arrived there straight from the Wehrmacht. The Waffen SS was beginning to lose its specific SS cohesion as many of these men had little contact with the dogma that had been drilled into the early Waffen SS. The military tasks that the Waffen SS was asked to perform induced its commanders to conform to codes of conduct prevailing in the army. Much to Himmler's annoyance, there was a tendency to use army rather than SS ranks. Likewise, the colour of uniforms and equipment was often assimilated with those of the army. Differences between the armed SS and the army declined with the experience of front line combat, while the estrangement from the non-military SS grew. In October 1941, for example, it was reported that Sturmbannfuhrer Loh, the Waffen SS garrison commander at Nuremberg, refused on principle all contact with General SS and SO officers (Hahne, 1969, p 447). Among the officers around Steiner in the Deutschland regiment, opinions could be heard that ran counter to those of the party, according to Himmler. There were demeaning remarks about the General SS, as well as a willingness to criticise the decisions of superior SS agencies.

In correspondence dated 7 November 1942, Himmler complained to Hausser that 'everything and everyone' were being criticised, from 'military measures which originate with the Reichsfuhrer, to political measures taken in the police sector' (cited in Wegner, 1990, p 193). There is certainly plenty of evidence that Waffen SS commanders were suspicious of their fellow SS officers, the Senior SS and Police Chiefs (HSSPF). On 5 March 1942, Himmler asserted that the HSSPF were 'allowed to help the Waffen SS, but otherwise these bothersome outsiders are not to be heeded' (Himmler to H Juttner, cited in Wegner, 1990, p 195). It is worth stressing, however, that although the SS commanders of elite units may have let their men criticise the regime and its agencies, in Steiner's Viking Division, the most rebellious unit, criticism of Hitler himself was out of the question (Wegner, 1990, p 194). The policies of the regime were questioned, but the correctness of Hitler's vision was accepted and the question was how to implement the Fuhrer's ideals.

Nevertheless, Himmler certainly believed that there was a danger that the armed SS would lead its own existence and withdraw into its own world, pleading exigency of war. On 23 November 1942, Max von Herff, head of the SS Personnel Office, told the Reichsfuhrer that there was 'a circle around Hans Juttner of the Waffen SS Head Office which must be watched. Neither their thoughts nor desires are those of the SS. They simply wish to be an imperial guard, anything else is a side issue in their eyes' (Hahne, 1969, p 479). To what extent the ideological chains linking Juttner's army to the SS parted as the war progressed is unclear. Certainly, leading Waffen SS officers began to despair of final victory and felt handicapped by second-rate replacements. The most interesting manifestation of this estrangement can be seen in the contacts between SS generals and the resistance. If we are to believe those involved, it appears that both Sepp Dietrich and General Willi Bittrich, commander of II SS Panzer Corps, expressed dislike for the regime to Rommel, while Hausser stated the same opinion to Colonel von Gersdorff. Their comments awakened hopes among the plotters that at least some of the SS units would remain neutral should the regime be overthrown. Fritz von der Schulenburg, a key resistance figure, attempted to establish contacts with Steiner and Hausser in 1943. Steiner was certainly involved in a conversation with him, even if there were no concrete results (Wegner, 1990, p 196).

It is highly doubtful that the leading SS generals were involved in planning a revolt. A minority, though, were distancing themselves from the regime when the war took a turn for the worse. Most, however, remained loyal to the bitter end. Indeed, the notion that the Waffen SS was becoming like the army requires qualification. As late as 1944, two-thirds of senior Waffen SS officers were still those who had been members of the General SS before joining the armed SS.

Every second higher Waffen SS officer had been a party member before joining. (These were men like Kurt Meyer, commander of the 12th SS Panzer Division, who, even as a prisoner, told his interrogator: 'You will hear a lot against Adolf Hitler in this camp, but you will never hear it from me. As far as I am concerned, he was and still is the greatest thing that ever happened to Germany.' Cited in Hastings, 1984, p 124). Equally revealing was the fact that a quarter of the Waffen SS generals in 1944 had been from the 'old guard' and joined the SS during 'the time of struggle' prior to 1933 (Wegner, 1990, p 268). It is doubtful that such men would have changed their views much as the war progressed. Many of the officers from the army without an SS background were ex-Freikorps men, so a consensus on Nazism would have remained. This kept the militarised formations under the same ideological roof as the rest of the SS. In the final years of the war, many posts in the Waffen SS were filled by the fanatics of the Hitler Youth (Their commitment was evident in the fact that the division they formed was entirely destroyed at Normandy in 1944, the handful of survivors only surrendering when they had run out of ammunition. When the division reformed with a new intake of Hitler Youth, it proved its fanatacism once more when sent to defend Budapest. In the spring of 1945, only 455 men survived by the time the city fell to the Russians. See Quarrrie, 1986, pp 133-7). The vast majority of Waffen SS men had thus been exposed to Nazism in one way or another. For these men, therefore, joining the Waffen SS was likely to have been more than a question of military ambition.

The armed SS would have served to strengthen Nazi convictions due to its status as the Fuhrer's 'Imperial Guard'. Men like Hausser may not have been revolutionary racists like Eicke, but they held a set of beliefs that made a career in the SS possible. Although their views were similar to those held by most Wehrmacht generals, they had joined the Waffen SS because they saw it as a distinctive force with its own characteristics. As we have seen, these characteristics included its political status as an arm of the party and its fighting spirit in adversity. However, it also differed from the Wehrmacht in the extent of its barbarity. Our analysis of SS ideology has demonstrated how atrocities could be justified in what was defined as a war of annihilation, one where the existence of Germany was at stake. At the same time, the close organisationallinks with the rest of Himmler's empire meant that the Waffen SS was to be called upon to perform tasks that the army was rarely involved in.

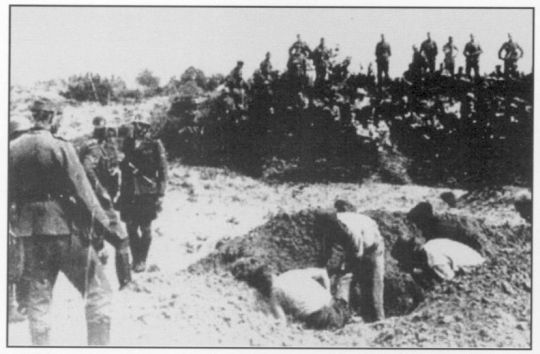

Waffen SS men from an Einsatzkommando watch civilians dig their own graves prior to execution. (Photo: Angelray Books)

What is clear, however, is that while the Wehrmacht's crimes were spontaneous, the Waffen SS had to provide men for the Einsatzgruppen squads from the outset. Einsatzgruppen A's personnel consisted of 9% Gestapo, 3,5% SO, 8,8% auxiliary police, and 34% Waffen SS, the remainder being technical personnel (Hahne, 1969, p 358). The Totenkopf in particular had close links with the Einsaztkommando. In October 1941, when the division's losses became grave, the company from the battalion then serving with Einsatzgruppen A were transferred back to the division. A secret SD document of September 1941 documented the reliance of the Einsatzgruppen upon the Waffen SS men to do the actual shooting of Jews (Sydnor, 1989, p323).

As the invasion of the Soviet Union continued, the first wave of Einsatzgruppen were followed by the SS and Police Leaders (HSSPF) who were engaged in 'anti-partisan' actions, a euphemism for killing anyone that the Einsatzgruppen had missed. Here, too, the Waffen SS helped out. In a report on the action of the 2nd SS Cavalry Regiment in the Pripet Marshes from 27 July to 11 August 1941 (Kriegstagebuch des Kommandostabes Reichsfuhrer SS Vienna, 10/956, pp 20-1, cited in Y Arad et al (eds), 1987, p 414), SS Sturmbannfuhrer Magill reports that the 2nd SS Cavalry Regiment had assisted the HSSPF in killing 6 526 'Jewish looters, communists and secret members of the Red Army', but that 'the driving of women and children into the marshes did not have the expected success, because the marshes were not so deep that one could sink'.

Another example of Waffen SS participation in extermination is the report by SS Brigadefuhrer and Major General of the Police, Jurgen Stroop, of the destruction of the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw during April and May 1943. Among the units involved were two Waffen SS battalions that came in for high praise from Stroop: 'Considering that. .. the men of the Waffen SS had been trained for only three or four weeks before being assigned to this action, high credit should be given for the pluck, courage and devotion to duty' (Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression,Vol II, pp 173-237, document reference 1061-PS').

The selection methods and ideological education of Waffen SS men furnished such good grounding that a few weeks of practice was all that was required to turn them into excellent exterminators. This was not the only occasion on which the armed SS was engaged in a savage act of reprisal in Warsaw. On 1 August 1944 the Polish resistance rose in revolt in an attempt to liberate their capital before the Russians arrived. The revolt was put down by Waffen SS Obergruppenfuhrer and General of the Police Erich von dem Bach-Zalewski, a former Einsatzgruppen commander. He had been ordered by Himmler to raze the capital and exterminate its population. Over 200 000 civilians died in what was the largest single atrocity of the war (Overy, 1997, p 246).

Hausser and Steiner had to accept in their ranks men like Bach-Zalewski, Stroop and Haupstormfuhrer Bothman, an equally unsavoury character who had served at the Chelmno death camp where he helped operate the gas vans (Hahne, 1969, p 465). They had to serve alongside Oskar Dirlwanger, a convicted child molester. His brigade was eventually designated the 36th Waffen SS Grenadier Division and consisted of convicted criminals. When Dirlwanger's unit was involved in the reduction of the Russian 'Partisan Republic of Pelik' some 15 000 'partisans' were wiped out. The unit reported, however, that only 1 100 weapons were found. A horrified civilian propaganda officer complained that some of the partisans had been burnt alive and their halfroasted bodies eaten by pigs (Reitlinger, 1981, P 174).

The Eastern Waffen SS was equally brutal. In the Balkans, the racial Germans behaved with such barbarity that Sturmbannfuhrer Reinholz of Einsatzkommando 2 protested against their inhuman methods, which had begun 'to have an injurious effect upon German interests'. (Often, the mere presence of Waffen SS men was enough to erode what little sympathy there was for the Germans among the people of the occupied lands. The inhabitants of one Ukrainian town, an OKW report of 2 August 1943 noted 'are in a state of permanent indignation over the thefts of livestock, assaults on inhabitants, and rape of women'.

Waffen SS men execute a civilian suspected of partisan activities.

(Photo: Angelray Books).

The report concluded that 'prior to the arrival of the armed SS the population was most favourably disposed towards the troops'. See Hahne, 1969, pp 469-70). On 28 March 1943, for example, a battalion from the Prinz Eugen Division murdered 834 civilians at the villages of Dorfu Otok, Cornj and Dola Delriji in Dalmatia. During their retreat from an area near Poporaca in Bosnia, the division's 1st Mountain Brigade shot every civilian they came across, maintaining that it was impossible to distinguish the local people from partisans (Butler, 1989, p 231).

The SS military commanders may have believed that they were separate from murderers like Dirlwanger and the Eastern SS, but the elite units themselves were often responsible for atrocities. In 1941 a detachment from the Viking Division shot 600 Jews in Galicia as a reprisal for 'Soviet crimes' (Hahne, 1969, p 469). In October 1941 the Waffen SS were engaged during a civilian state of emergency in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. They took part in shootings and supervised the hanging of 191 individuals in Prague and Bruenn. In July 1944 Das Reich, searching for an SS officer captured by the Maquis, destroyed the village of Oradour-sur-Glane near Limoges in France and murdered 642 civilians (Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Vol II, pp 237-48, document reference 1972-PS).

Waffen SS personnel were even involved in medical experiments on concentration camp inmates. Oberfuhrer Joachim Mrugowsky, Chief of the Hygienic Institute of the Waffen SS, took part in high-altitude experiments at Dachau for the benefit of the Luftwaffe. The experiments were carried out in a low-pressure chamber in which atmospheric conditions prevailing at high altitude could be duplicated. He also took part in tests to investigate ways of treating people who had been severely chilled. In one series of experiments the subjects were forced to remain in a tank of ice water for three hours. Sturmbannfuhrer Viktor Brack of the Waffen SS was engaged in sterilisation experiments conducted by means of drugs, X-ray and surgery at Auschwitz and Ravensbruck (Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No 10. Nuremberg, October 1946-April 1949, US GPO, Washington, DC, 19491953, P 12).

It is not surprising that units of the Waffen SS, which had thus been employed for medical experiments, extermination actions and the execution of civilians, also violated the laws of warfare. Political fanaticism, combined with the fury of battle, led to repeated breaches of the established codes of warfare. There occurred in Normandy, for example, between 7 and17 June 1944, seven cases involving the shooting of 64 prisoners. The 25th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 12th SS Panzer Division were given orders stating that prisoners were to be executed after having been interrogated. Similar orders were given to the 3rd Battalion of the 26th SS Panzer Grenadiers, and to the 12th SS Engineering and Reconnaissance Battalions (Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Vol II, pp 237-48, document reference 2997-PS).

It must be said, however, that there were numerous cases of Allied soldiers shooting SS prisoners during the Normandy fighting. In the heat of battle, after having seen friends die, many men found it intolerable to send prisoners to the rear knowing that they would thus survive the war, while they themselves seemed to have little prospect of doing so (Hastings, 1984, p 211). The difference however, was that the cases of Allied troops shooting prisoners were random and spontaneous, while the Waffen SS often held to a definite policy of liquidating prisoners. During the Ardennes offensive, elements of the Leibstandarte murdered American prisoners at Malmedy after they had surrendered. Even earlier in 1940, the man responsible for this atrocity, Wilhelm Mohnke, had led the massacre of British prisoners at Wormhoudt in France. The killing of allied prisoners in the West destroyed the myth that the Waffen SS only reserved its excesses for the Eastern front, where the murder of Soviet POWs was a regular feature of the fighting.

Conclusion

It is more than likely that had a long war of attrition not intervened, the Waffen SS would never have become such a famous military machine. Instead, it would have remained a brutal paramilitary police force, as the Nazis originally intended. Our brief look at the origins of the Waffen SS demonstrates that it developed from the General SS and was not a separate organisation. Conversely, there is evidence in the military training and organisation of the armed SS before the war that it was planned as a combat formation from the outset as well. Himmler wanted his political soldiers to serve in the east as well as within the Reich. The transformation of a small emergency force into a vast army did not, however, result in any separation of the armed branch from the rest of the SS. Although tactically under the command of the Wehrmacht while in the field, it remained as much a part of the SS as any other branch of that organisation. Throughout the war it was recruited, trained and administered by the main offices of the SS Supreme Command. Ideologically and racially its members were selected in conformity with SS standards.

The notion that the Waffen SS was almost out of SS control is incorrect. Despite disobeying orders, personality clashes and disputes, the armed SS fought on to the end for their Reichsfuhrer. From the outset the armed SS was imbued with Nazi zeal, the only disputes were how to use the Waffen SS to further this ideology. All of Himmler's principles may not have always been reflected in the Waffen SS, but the core belief in the ideal remained in the elite units, even if they did start to develop their own, at times rebellious, identities. At the same time, Hitler's interest and thus his authority over the Waffen SS remained constant until the end, whether this was in decrees concerning its role or the posting of elite divisions to areas in crisis.

This discussion has documented the characteristics and beliefs of the men who organised, built, and served in the armed SS, and the various purposes for which they were used. It seems the Waffen SS, consisted of 'heroes' and 'murderers'. Men like Steiner and Hausser were soldiers whose war-time record was unblemished. However, individuals such as Eicke, Stroop and Dirlewanger can only be described as murderers. The majority of Waffen SS men fell somewhere in between. It would be wrong to attempt to excuse the armed SS of its crimes as the post-war apologists have done, or to condemn totally all those who served in an organisation whose creation and development they did not control.

Many soldiers served in the Waffen SS because they were conscripted or transferred. To 'suggest that all these men were sadists, criminals and fanatics would be as ludicrous as the attempts by apologists for the Waffen SS to prove that the armed SS was not really part of the SS' (Sydnor, 1989, p 343).

Years of indoctrination and SS training had worked well and produced some of the most destructive forces in history. The combat records of many of the Waffen SS divisions was indeed remarkable. However, it was only the elite units that created this legend. The majority of the Waffen SS was moderate at best. Despite any admiration historians may have for the elite divisions' fighting qualities, it does not justify the disregard of the Waffen SS for moral and humane codes of conduct. It is not that the Waffen SS exchanged personnel with the more sinister aspects of Himmler's empire, nor that it included in its ranks organisations like the Dirlewanger Brigade, nor that Waffen SS units took part in acts like the repression of the Warsaw ghetto. It is rather the case that, willingly and in the normal course of action, the elite divisions, having adopted a different philosophy of war, were too often themselves the perpetrators of atrocity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(See also Bibliography to Part I, Military History Journal (incorprating Museum Review), vol 12 No 5. June 2003, p 183).

Arad, Y, Gutman, Y, Margaliot, A (eds), Documents on the Holocaust (Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1987).

Butler, R, The Black Angels: The Story of the Waffen SS (Arrow Books, London, 1989).

Foerster, J, 'Wehrmacht, Krieg und Holocaust' in Dieter Mueller, R and Volkmann, H E (eds), Die Wehrmacht: Mythos und Realitat (R Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich, 1999).

Gerlach, C, 'Deutsche Wirtschaftsinteressen, Besatzungspolitik und der Mord an den Juden in Weissrussland, 1941-1943' in Herbert, U (ed), Nationalsozialistische Vernichtungs-politik, 1939-1945: Neue Forschungen und Kontroversen (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1998).

Gingerich, M P, 'Waffen SS recruitment in the "Germanic Lands", 1940-41, in Historian, Vol 59, No 4,1997, pp 815-30).

Hastings, M, Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy (Book Club Associates, London, 1984).

Hahne, H, The Order of the Death's Head (Secker and Warburg, London, 1969).

Keegan, J, The Waffen SS - The Asphalt Soldiers (Macdonald, London, 1970).

Landwehr, R, Charlemagne's Legionnaires: French volunteers of the Waffen SS, 1943-1945 (Bibliophile Legion Books, Silver Spring, 1989).

Lepre, G, Himmler's Bosnian Division: The Waffen SS Handschar Division 1943-45 (J J Federowicz Publishing, Winnipeg, Canada, 1999).

Luther, C W, The 12th SS Panzer Division 'Hitler Youth': Its Origins, Training and Destruction, 1943-1944 (PhD thesis, 1987).

Nazi Conspiracy ond Aggression, Vol II (USGPO, Washington, 1946).

Overy, R, Russia's War (Penguin Books, London,1997).

Quarrie, B, Hitler's Teutonic Knights - SS Panzers in Action (Patrick Stephens Ltd, London, 1986).

Reitlinger, G, The SS - Alibi of a Nation 1922-1945 (Arms and Armour Press, London,1981).

Sayer, I and Bathing, D, Hitler's Last General - The case against Wilhelm Mohnke (Batam Press, London, 1989).

Sydnor, C W, Soldiers of Destruction - The SS Death's Head Division 1933-1945 (Guild Publishing, London, 1989).

Theile, K H, Beyond Monster and Clowns - The Combat SS, Demythologizing five decades of German elite formations (University Press of America, London, 1999).

Trials of war Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Low No 10. Nuremberg, October 1946 - April 1949 (US GPO, Washington, DC, 1949-1953).

Wegner, B, The Waffen SS - Organization, Ideology and Function (Blackwell, Oxford, 1990).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org