The South African

The South African

by DAVID SAKS

In the last days of 1895, a mounted column, 500-strong, supported by nine artillery pieces, crossed the Bechuanaland border into the Transvaal and set off for Johannesburg, gold-mining capital of the world. Their aim was to provide support for the disaffected British residents of the town, whom they expected to be simultaneously rising in revolt against the Transvaal Boers under President Paul Kruger. This curious episode was the infamous Jameson Raid, named after the man who led it, Dr Leander Starr Jameson.

The raiders were volunteers, officially acting without the knowledge or sanction of the British government. But the fact that they were almost all British and inspired by patriotic, imperial motives, made their incursion a forerunner and to someconsiderable extent a cause of the great Anglo-Boer War that would break out a few years later. In fact, although Britain sought to distance herself from the raid afterwards, it transpired that many senior figures in government, including Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, had been aware at least to some degree of a plot to overthrow Kruger. The fiasco considerably embittered Anglo-Boer relations.

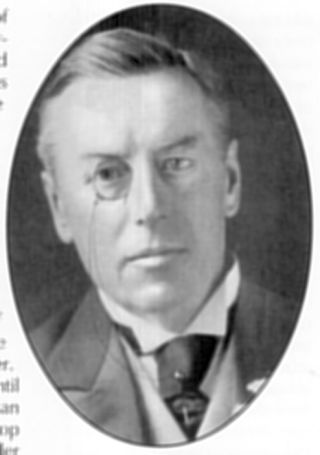

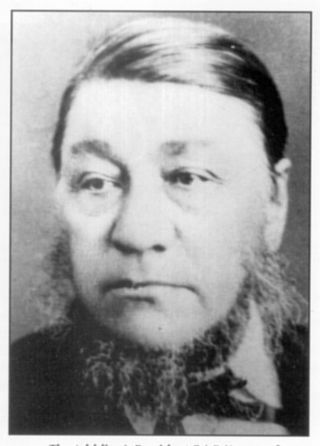

Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary at the time of the Raid.

(photo: By courtesy, S H Jeyes, Mr Chamberlain His life and public career, Vol II, Gresham Publishing, London, 1904).

The story of the Jameson Raid was a sorry record of recklessness, disobedience and impetuous folly. Yet nobody seems to have drawn parallels between it and two other famous historical events. These were the celebrated raid by American anti-slave activist John Brown on Harper's Ferry in 1858, and the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco on the Cuban coast. All three episodes took the form of small-scale military invasions aimed at provoking an uprising of disaffected locals and thereby overthrowing the ruling regime. In the case of Harper's Ferry, the locals were slaves, with the deluded Brown imagining that his raid would lead to a fullscale slave uprising. In the case of the Bay of Pigs, the locals were Cuban opponents of Fidel Castro. With the Jameson Raid, of course, the locals were 'Uitlanders', the British residents of Johannesburg who were expected to take up arms once the raid got underway and overthrow the Kruger republic.

All three ill-conceived schemes were disastrous failures. No local uprisings took place and the hapless invaders found themselves fighting alone against overwhelming odds until they were all killed or forced to surrender. Both Harper's Ferry and the Jameson Raid did much to provoke two gigantic conflicts a few years later, the American Civil War and the Anglo-Boer War respectively. Mercifully for humanity, the Bay of Pigs affair did not do the same.

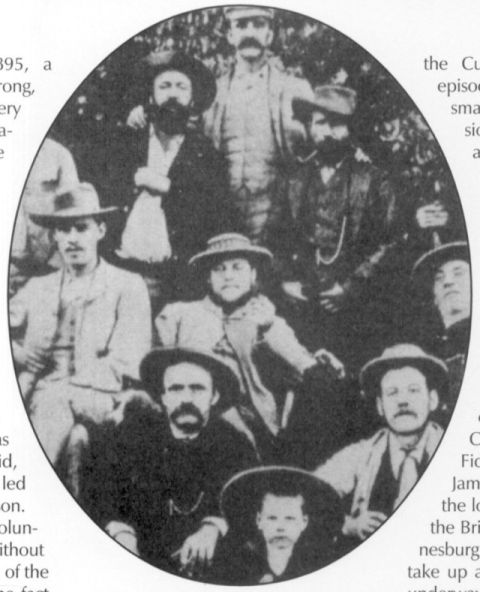

The Uitlanders were a diverse group of miners who were deeply dissatisfied with their treatment by the Kruger Government.

(Photo: By courtesy, SA National Museum of Military History [SANMMH]).

The Jameson Raid had its origins in the failure of the British immigrants of the ZuidAfrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) to be amicably absorbed following their arrival after the discovery of the Witwatersrand goldfields in 1886. The ZAR was established in 1852 following the northward migration of several thousand Dutch-speaking white inhabitants of the British-ruled Cape Colony. These migrants came to be referred to as Boers (literally 'farmers'), and it was by this name that they were generally known at the time of the raid.

In 1877, the ZAR was annexed by Britain, but reverted to Boer control in 1881 when the latter successfully rose in revolt and won a series of striking victories culminating in the dramatic British defeat at Majuba Hill. Britain's decision to let the territory go was shown to be premature five years later when what proved to be the world's richest goldfields were discovered in a range of low hills in the centre of the country known as the Witwatersrand. Thousands of immigrants, mainly, although by no means exclusively, British, began settling in the country, establishing the city of Johannesburg on the site of the first discovery.

Symbol of British humiliation - Majuba Hill, site of the British defeat in 1881.

(Photo: By courtesy. SA National Museum of Military History [SANMMH].)

Events leading up to the Raid

These immigrants, known as 'Uitlanders' or foreigners, soon began agitating for full political rights. They had other grievances against Kruger, among them the official favouring of certain monopolies, and nepotism. When attempts to resolve these by peaceful means failed, many Uitlander leaders began considering the more drastic remedy of violent revolution. In this they had the clandestine support of Cecil John Rhodes, a multi-millionaire and prime minister of the Cape Colony. Rhodes undertook to provide covert financial and military support.

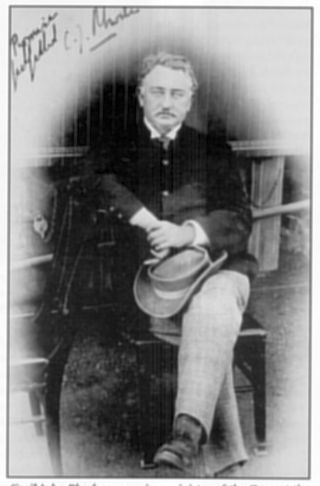

Cecil John Rhodes was prime minister of the Cape at the

time of the Raid.

(Photo: by courtesy, SANMMH).

In the latter months of 1895, plans for an uprising began to fall into place. In Johannesburg itself, the Reform Committee, the recognised representative body of the Uitlanders, began preparing to coordinate an uprising in the city, smuggling in arms and ammunition. At the same time at Pitsani, a small trading post across the border in British Bechuanaland, now Botswana, Rhodes' right-hand man, Dr L S Jameson, began mustering troops to be used in support of the incipient revolt. These were drawn mainly from the Mashonaland Mounted Police (MMP) and the Bechuanaland Border Police (BPP), all on the payroll of Rhodes' British South Africa Company. There were also a number of veterans of the 1893 war against the Matabele, an offshoot of the amaZulu in Natal who had migrated northwards across the Limpopo into what is today Zimbabwe. By December, Jameson had mustered just over 500 men, little more than a third of that for which he had hoped. Operational control of the force was in the hands of LieutenantColonel Sir John C Willoughby, Royal Horse Guards.

For all the elaborate plotting and planning, the whole enterprise looked like fizzling out once those on the Johannesburg side sensibly began to have second thoughts. The original date of the uprising had been set for 28 December 1895, but the reformers were hopelessly unprepared and decided to postpone it. This postponement might well have spelled the beginning of the end of the planned insurrection as the implications of actually going ahead with so madcap a scheme would have become increasingly apparent had Jameson not now made the fateful decision to kick-start matters himself by invading Boer territory. Jameson, an impatient and impulsive man with the fateful temperament of a gambler, evidently hoped that once his invasion was underway, the Johannesburg uprising would be precipitated more or less automatically.

Dr Leander Starr Jameson, leader of the raiders and Rhodes' right-hand man.

(Photo: G Seymour Fort, Jameson, Hurst & Blackett, London, 1908).

The raiders were to move into the Transvaal in two columns: the MMP, 372 in all, to proceed from Pitsani, and 122 BBP to simultaneously set out from Mafeking. The two wings would join up at Malmani, about 40km inside the Transvaal border, and from there make for Johannesburg. The artillery battery comprised two 7 pounders, one 12.5-pounder, and eight Maxims. There were also a number of ambulance wagons.

At 18.30 on Sunday, 29 December, the invasion began. The two columns rode through the night and reached Malmani more or less simultaneously at 05.00 the next day. One of the first things Willoughby had ordered was for the telegraph lines to be cut. The wrong ones were cut, however, and to the end the Boers were always well aware of what was going on throughout the operation. Within a short time they began mustering a 'commando', the traditional name given to a body of mounted irregulars called up on an ad hoc basis from amongst the Boer citizenry when crises arose. The ZAR did not have a standing regular army.

The column rode throughout the day of 30 December without meeting any resistance. Late in the afternoon, a Boer messenger handed Jameson a letter from Piet Joubert, Commandant-General of the Republic, demanding to know exactly what he was doing, and ordering him to turn back immediately. Jameson's response was a polite refusal and all subsequent directives, most of which came from the Uitlander leadership or the British authorities, were similarly turned down. He was fast approaching the point of no return and one wonders at what stage he, and Willoughby too for that matter, realised that the enterprise was doomed to fail.

At midnight on New Year's Eve, the weary troopers heard a sound that would become all too familiar during the next few days - the crackle of Mauser rifle fire. The advance patrol of the column had been in the process of crossing a rocky, wooded ridge when about forty concealed Boer snipers had opened up on it. Reinforcements were quickly brought up and a short skirmish ensued, one trooper of the MMP being wounded before the Boers broke off the action and melted away into the night.

By mid-morning on 1 January 1896, the column was approaching Krugersdorp, a mining village north-west of Johannesburg. Until then the Boers, still lacking a numerical advantage and well aware of Jameson's artillery battery, had been content to hover on his flanks. Now it was learned, from two British cyclists, that several hundred Boers were awaiting the column on the outskirts of Krugersdorp. The raiders halted at Hind's Store, which belonged to a British sympathiser of that name and had been designated in advance as a stocking-up depot. They rested for an hour and a half before resuming the advance along the south road through some mining properties.

Looming up ahead of the troopers and straddling the road was a long, low ridge, and it was along this feature that the Boers had deployed. The ground was ideal for defence. On the summit was a disused iron shed, surrounded by mud heaps thrown up by miners and this provided a natural fort with ready-made earthworks. To the south, some old prospector's cutting provided pre-dug rifle pits and further north a farmhouse and plantation supplied additional cover. In the depression between the raiders and the waiting Boers lay a shallow vlei, crossed by the road at a narrow drift.

The column was by then being shadowed by Boer horsemen, who hung on the fringes, just out of range. As the advance progressed, these would begin closing in, relentlessly harassing the troops from the flanks and rear with long-range sniper fire. Finally, once the troopers had been herded into a cul de sac, the Boers would dismount and close in for the kill. But that was still twenty hours into the future.

The extreme peril of being more than 100km inside hostile territory, and facing growing bodies of enemy horsemen, had evidently not yet dawned on Colonel Willoughby. With remarkable arrogance, he sent a message to Commandant Malan in Krugersdorp, informing him that, should his 'friendly' force be opposed, he would be compelled to shell the village. Malan was given until 16.00 to evacuate the women and children.

How a heavily armed column that had already invaded a sovereign state, damaged its property, fired on its citizenry and was now threatening to bombard one of its settlements could be described as 'friendly' is yet another bizarre aspect of the whole sorry affair! Perhaps Willoughby still believed that the Boers would offer no more than a token resistance. At any rate, no reply was forthcoming from Malan and at 16.30 the two seven pounders and the 12.5-pounder began raining shells on the sprawling Boer lines at a range of 1 900 yards (l,74km).

Before the opening of the artillery barrage, Jameson could still have called off the whole thing. Until that point, despite the wire cutting and light skirmishing that had taken place, the raid had been not much more than an armed promenade. Had the column turned back then, it is likely that the Boers would have done no more than keep a watchful eye on it until it was safely back over the border. Now, however, the gauntlet had well and truly been thrown down, and it was too late for any second thoughts. The invaders could only battle their way through to Johannesburg, or surrender.

The bombardment itself was a waste of ammunition. The Boers were too well protected, and when Willoughby finally called a halt, not one had even been wounded. The raiders watching the fun on the opposite rise had no way of knowing this. Instead, the apparent accuracy of the shelling and the virtual silencing of the snipers might have given them the impression that their opponents had suffered heavily and would be in no position to withstand a determined charge. One of their number managed to spy out part of the Boer position and returned with a report that many must have been killed since all he had seen were motionless bodies. The Boers, of course, were merely lying prone until the artillery practice was over.

The bombardment lasted until 17.00. Soon after it ended, an advance guard, comprising a troop of 100 men of the MMP under Lieutenant-Colonel Harry White and two Maxims, rode forward into the attack. White was supported on either flank by two further troops, each with a Maxim. At the same time, Lieutenant-Colonel Raleigh Grey was detailed to take one troop of the BBP and a fifth Maxim and assail the Boer left. The remaining two troops and guns formed the reserve and rearguard.

If nothing else, White's men at least made an impressive sight. The watching Boers could not help but admire the way in which they fanned out at the word of command. A narrow cluster of horsemen suddenly opened out to the right and left and swept on in open order, a single long line of mounted riflemen, cheering as they rode. Only when the horsemen entered the vlei itself did the hidden Boers open up, and a devastating crackle of rifle-fire rippled out all along the ridge and from the flanks. The charge was stopped in its tracks almost immediately.

With riders and mounts being cut down on every side, White's men halted, dismounted and, seizing whatever cover was available, began returning fire as best they could. To relieve the pressure on them, the left support under Inspector Dykes of the BBP attacked the Boer right, only to be driven back by a fierce flanking fire from the farmhouse and plantation when it advanced too far. Grey's detachment likewise made little headway as it came into action on the extreme right of the British line. White's position in the vlei was obviously untenable.

Those who could, remounted and galloped back the way they had come while the remainder tried to take cover amongst the reeds. In the end, less than half of the original advance guard rejoined the main body. Those not killed outright were taken prisoner when the Boers moved down from the heights and surrounded them.

The feelings of Dr Jameson and Colonel Willoughby as they watched their men being beaten back so effortlessly can only be imagined. What must have become suddenly and brutally clear was that there was going to be no easy victory. The expedition, no longer a daring adventure undertaken by spirited young Englishmen, had all at once turned into a grim struggle for survival against enormous odds. Willoughby called off the attack, detailing Inspector Drury to cover the rear with one troop MMP and a Maxim while Grey covered the left flank with two troops BBP, the 12.5-pounder, and a Maxim. Grey's artillery gained a small triumph during the withdrawal when a direct hit blew up the iron shed on the summit that the Boers had used as a battery house.

Willoughby continued south, hoping to turn the Boer position and slip through to Johannesburg under cover of darkness. He might just have succeeded in this, had he not heard the sound of heavy firing from the direction of Krugersdorp soon after his men moved off. Ever optimistic, he interpreted this as signifying the belated arrival of reinforcements from Johannesburg and hurried back to lend assistance.

When he reached the scene, however, he found that the firing had greeted the arrival of reinforcements for the Boers.

A large contingent of burghers had arrived from Potchefstroom and the Boers on the ridge had fired off a few celebratory rounds to welcome them. By the time Willoughby learned this, the chance of reaching Johannesburg had been lost. The Boers had outflanked him and sealed off the southern road. All he could do now was bivouac for the night and try to find an alternate route in the morning.

What followed must have been a harrowing and uncomfortable night for the exhausted troopers. Thick clouds blotted out the moon and would have rendered the camp invisible had one of the lights in the ambulance wagon not been left burning. The Boers on the plateau overlooking the bivouac poured a steady stream of bullets into the camp from distances ranging between 400 and 800 metres. The British were fairly well protected but nevertheless lost two more killed as well as a number of horses. They were without food and had only a small quantity of muddy water to drink. It is a testimony to their fortitude that, far from complaining or threatening mutiny, they stuck to their increasingly hopeless task with a coolness and determination worthy of a better cause.

At 03.30 on 2 January, Willoughby prepared to move off again. Patrols were sent out on all sides and returned half an hour later to report that only the ground to the south was free of the enemy. It was in this direction, therefore, that the column setoff. WhatWilloughby did not realise at the time, although it would become obvious later, was that far from being negligent in leaving their opponents an escape route, the Boers were in fact patiently and systematically shepherding them into a trap. The hapless raiders, although they continued to sally out with their customary discipline and orderliness, were in effect puppets on a string, unable to maintain any sort of control over their destinies, let alone dictate the course of events.

The whole wretched venture was now entering its closing stages. Harried every step of the way by long-range sniper fire, the column began moving in an easterly direction towards Randfontein, another mining village. Vleis, swampy ground and a railway embankment slowed its progress. To cover the rear, White was detached with one troop and two Maxims while the rest of the men pressed on as rapidly as they could. A 10km long running fight ensued, the Boers keeping their quarry in their sights without attempting to close with them ..

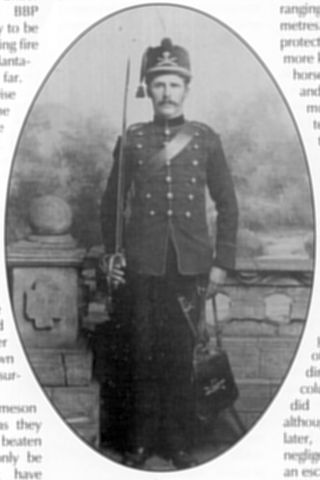

The Staatsartillerie was called out from Pretoria to deal with the Raiders.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

The Staatsartillerie was still being brought up from Pretoria and they had no desire to provide unnecessary targets for the field guns and Maxims. With hindsight, the eventual running to ground of Jameson's harried band is seen as being inevitable, but this is not entirely true. With luck, they might even then have slipped through the net and reached Johannesburg, although what they would have achieved then is questionable.

The raiders had a brief respite at Randfontein, where many of the locals were English-speaking and cheered them on. Then they pressed on, still running the gauntlet of long-range sniper fire, which whipped in at them from three directions as they cantered wearily across the veld. Willoughby now learned that the Boers were at last making a stand, taking up a position on the hill of Doornkop which lay directly in the column's path and beyond which were Johannesburg's western districts.

Hurrying to the front, he found his men shelling a low ridge, which he assumed to be Doornkop. The BBP attacked the ridge and carried it with the loss of a handful of men, and the rest of the column followed up. At this point, Willoughby discovered his error. The real Doornkop was still in his path, steep and stony and with dozens of waiting Boers crouched behind its boulders. To make matters worse, on the right was a second ridge, from where the Boers could pour a withering crossfire on the troops exposed on the brow of the rise.

The raiders made one bold attempt to clear the Boer positions before they could be reinforced. Captain Barry and a party of MMP sallied out gamely to dislodge the burghers on the hill, but five times as many men were, needed and they were quickly beaten back. Barry himself was severely wounded in the groin and spine. It was Willoughby's last chance to break through since Doornkop at the time was still not strongly held. Soon after this, Commandant - roughly the Boer equivalent of a 'colonel' - Piet Cronje arrived with 150 men. With that, the trap finally snapped shut.

Caught in a cul-de-sac, unable to advance or retreat, the game was almost up for Jameson's battered raiders. The doctor himself, shattered by the series of misfortunes that had befallen his reckless enterprise, had long since ceased to play a leading role in events. Until then, he had counted on a relieving force coming out from Johannesburg. Now, even that slender hope was dashed as a message arrived from the town informing him that the Reform Committee were not about to send reinforcements nor had they ever considered doing so.

In fact, about 100 Uitlanders did set out at one point to join up with the raiders but they were quickly recalled once the Reform Committee heard of this. The plotters in Johannesburg knew they were for it, and had no wish to make matters worse. Many would end up in prison, in some cases after death sentences had been commuted. Meanwhile, the British High Commissioner, Sir Hercules Robinson, had declared Jameson an outlaw, issuing a proclamation forbidding British subjects to assist him. The Johannesburg plotters were glad enough of an excuse to do nothing. The troopers spread out to take up what was to be their last stand. They were occupying a farm, called 'Vlakfontein', and hence had a number of structures behind which to take cover. Their main body, and the guns, occupied an abandoned kraal, and began returning the fire of the encircling Boers. The latter began pressing forward, working their way around the column's left flank. The British had outnumbered them at the beginning of the fight, but no longer as more and more reinforcements arrived. They too suffered casualties. A number on the ridge were shot down as they leaned over to fire. Some of the rocks behind which they had been crouching were found afterwards to be white with bullet marks.

How long the unequal duel could have continued in this way is debatable. Though outnumbered and exhausted, Jameson's men were still fighting back stubbornly and the field guns continued to pound away even after the Maxims had grown too hot and had jammed. Then came the final blow. Dark objects could be seen approaching along the dirt road to the west as the sun rose and the glint of sunlight on metal revealed them to be the Boer artillery, arriving at last from Pretoria. Minutes later, they were opening fire at less than a kilometre's range.

Willoughby decided to throw in the towel at last.

At around 09.00 on 2 January the Boers saw a white banner waving over the outhouse of the farmstead. To add insult to injury, it was not even a formal white flag, only an apron borrowed from an old coloured woman who happened to be in the vicinity. The battle of Doornkop was over and, with it, Jameson's reckless bid for glory. The jubilant Boers came galloping down from all directions while their opponents stacked their arms and waited resignedly to be taken prisoner.

The aftermath

The Boers should be given credit for the way in which they dealt with the invasion. They had shown considerable tactical skill and guile, firstly in wearing down Jameson's well-armed column, and then in running it to the ground with relentless efficiency. They took no unnecessary risks. Boer casualties in the defeat and capture of 500 mounted infantry supported by artillery amounted to a mere four killed and a handful wounded. For their part, the raiders had no cause to feel ashamed. Most had stuck uncomplainingly to their task, fighting tenaciously with their backs to the wall while hopes of relief faded. Their casualties were over 100, about 20 per cent, and were made up of 17 dead, 55 wounded and 35 missing. The bulk of the latter were presumably deserters. Given the duration of the fight, these losses were not especially heavy, suggesting that the Boer tactics had ultimately minimized casualties on both sides.

The 'old lion', President S J P Kruger of the ZAR.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

The Jameson Raid further soured relations between Britain and Kruger's republic, and brought the two sides a step closer to war. In the end, the Union Jack would fly over Johannesburg after all, although it took nearly three years and half a million men to achieve this. Oddly enough, while the fiasco brought the political career of Rhodes to a humiliating end, it does not seem to have hampered Jameson's subsequent political career. After the Anglo-Boer War, he became prime minister of the Cape Colony, and served briefly as leader of the opposition in the Union Parliament after the four South African colonies merged in 1910. The fact that few people know this, however, suggests that he will always be remembered less for his political activities than for the foolhardy and disastrous raid that has ever since borne his name.

| The Raiding Column | |

|---|---|

| OC: Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Willoughby, Royal Horse Guards. | |

| Mashonaland Mounted Police | |

| Officers and Men | 372 |

| Staff | 13 |

| Drivers/servants | 65 |

| Horses | 480 |

| Mules | 128 |

| Carts | 7 |

| Grain wagons | 2 |

| 12.5 pounder | 1 |

| Maxims | 6 | Bechuanaland Border Police |

| Officers and men | 122 |

| Staff | 1 |

| Horses | 160 |

| Mules | 30 |

| 7-pounders | 2 |

| Maxims | 2 | TOTAL |

| Officers and men | 494 |

| Staff | 14 |

| Drivers/leaders etc | 75 |

| Horses | 640 |

| Mules | 158 |

| Maxims | 8 |

| 7-pounders | 2 |

| 12.5 pounder | 1 | THE BOERS |

| Commanders: | Commandant Piet Cronje, supported by Commandants Trichard, Potgieter and Malan. |

| Burghers: | Unknown, approximately 1 000 mounted riflemen. |

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org