The South African

The South African

By Cliff Lord (c)

A young Marconi engineer, Reginald Kenneth Rice, was sent to Mombasa in1914 to install a wireless transmitter and receiver. The decision had been made in 1913, for commercial purposes only. By the end of December1914, the station was working, but had not yet been handed over to the civil authorities as a fully operational wireless station. Owing to the military situation in East Africa at the time, a decision was made to apply the equipment to military purposes.

Some experiments were carried out by transferring the receiver to the steamer Clement Hill, which had scheduled runs across Lake Victoria between Entebbe and Kisumu. The purpose of the experiments was to check the feasibility of the receiver intercepting German radio transmissions from Mwanza with its subsidiary station at Bukoba. The trial was a success and a receiver was set up at Entebbe.

Initially, the German transmissions were in clear, but were later coded. This presented a problem for Rice and his operators. It was overcome by telegraphing the coded signals to Mombasa, where they were cabled via Zanzibar and Aden to Bombay for overland transmission to Simla. There they were broken down by the Indian Army experts, and the contents sent to Nairobi over the same route. On 23 November 1914, Rice was appointed Director of Land and Wireless Telegraphs, with the local rank of captain.

Even so, Rice still had obligations to Marconi, and had to fulfil his duties to complete the Mombasa wireless station and hand it over as a going concern to the civil authorities. The German station at Bukoba was destroyed on 23 June 1915, but the Mwanza station continued to function until 14 July 1916. However, Rice was not in East Africa to see this because he had handed over the Mombasa wireless station on 15 April 1915. On 18 April, he had resigned his appointment as Director of Land and Wireless Telegraphs and had sailed for the Seychelles, where he remained in charge of the naval wireless station until the autumn of 1917.

Military signalling in East Africa continued after the war within the King's African Rifles (KAR). Signals relied largely on recruiting from the Wakamba tribe. In the new scheme for the KAR outlined to the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1929, the regiment was to be re-organised in two formations. This included a Northern Brigade serving in Kenya and Uganda with headquarters in Nairobi, and a Southern Brigade serving in Tanganyika and Nyasaland with headquarters at Dar-es-Salaam.

Each brigade was to be commanded by a colonel, who would act as military adviser to the governors of the dependencies in which his brigade served. Provision was made for communications within the brigades by signal sections consisting of one officer and one British NCO from the Royal Corps of Signals and 58 African other ranks drawn from battalions. Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, a detachment of fifty British Army Royal Signals personnel, under a warrant officer class two, was sent from Palestine to form the nucleus of the East African Force Headquarters Signals.

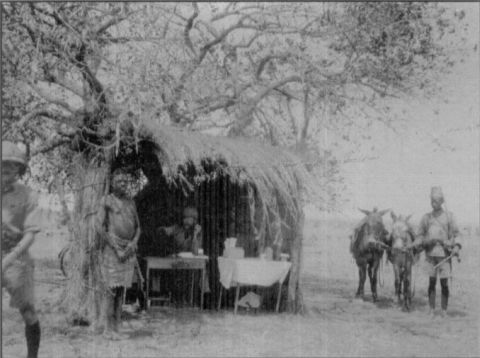

Lukegeta wireless (Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH, Vol 2, P 14)

The Brigade signal sections of the KAR had a closer resemblance to a lines of communication signals unit than a brigade unit. They provided communications throughout Karamoja, Turkana, Suk, and the Northern Frontier District. The Southern Brigade maintained communications throughout Tanganyika. Immediately prior to 1 September 1939, the European staff of the brigade sections comprised one captain and three warrant officers in the Northern Brigade, and one captain and one warrant officer in the Southern Brigade. All were regular soldiers seconded from Royal Signals. There were also six settlers earmarked to be signals officers. These were serving with the KAR reserve of officers, but were not called up until hostilities began.

From the KAR Brigade Signals, the East African Signal Corps (EA Signals) was formed on 1 September 1939. In 1940, EA Signals comprised two sections for 21 and 22 EA Brigades and the north and south area (Line of Communication signal units). Before the Abyssinia campaign started in January 1941, British Army Royal Signals personnel arrived from the United Kingdom to augment the fifty from Palestine to form the headquarters portions of 11 and 12 (A) Divisional Signals, 25 (A) Corps of Signals for advanced headquarters at Carissa, and a line of communications signal unit. The EA Signals line of communication units were then disbanded and formed the signal section for a third EA Brigade (25 EA Brigade).

Towards the end of the campaign, a fourth EA brigade was raised, 28 EA Brigade, with its signal section from EA Signals. Personnel from EA Signals were indigenes from Kenya, Nyasaland, Tanganyika Territory and Uganda. Initially led by officers specially seconded from Royal Signals, they were later commanded by locally trained European personnel.

The telegraph office at Kikhum, with the captain at the instrument. (Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH, Vol 4, P 44).

After the Abyssinia campaign, an EA Signal Training Centre (STC) was created. Initially it was situated in the KAR lines in Nairobi. Equipment was very limited, and much was improvised. Flag drill was taught as well as reading and sending on the signalling lamp and buzzer using morse code. With the tremendous expansion following mobilisation, it was necessary to build a new STC and depot. The site chosen was Karen Camp on the outskirts of Nairobi. Later it was to move to Nanyuki. It was considered practicable to train Africans for manual operating in the initial stages of the war, and a school was opened at Kabete for this purpose. The chief instructor was a specially selected Royal Signals officer. The supervisory staff of officers and NCOs were local European personnel, while the actual instructors were indigenes of the former KAR Signals who had been through the campaign.

The language of instruction was Ki-Swahili. The corps grew from 120 personnel in 1939 to nearly 1 500 by May 1943, rising to a peak in 1944 of 1 632 Africans trained and turned out for service in signals. In 1945, the numbers dropped to 666. There was less than half the supervisory and instructional staff, and one-tenth the official equipment and STC of comparable size in Britain. In due course, several additional brigade signal sections and two divisional signal units were formed, mainly with Africans trained to better than Royal Signals class three standards. Technical maintenance was provided by Royal Signals. Eleven Division, and 28 Independent Brigade Signals Section, served in Burma.

East African Signal Corps was a conglomerate of nationalities. Consequently, EA Signals was complex but flexible. The motto of the STC was: 'ENTER TO LEARN, GO TO SERVE'. In Ki-Swahili, 'INGIA KUJIFUNZA NENDA KUFAA'. European women from Kenya, Nyasaland, South Africa, the Rhodesias, Tanganyika Territory and Uganda, as well as West Africa, formed a Women's Territorial Service East Africa (WTS). They were often known as FANYs or First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, although they had no connection with that pre-war British unit.

The WTS was organised by Lady Sidney Farrar, and was commanded by her from the outbreak of the war until October 1942. About 100 WTS manned the signal office in Nairobi and provided a dispatch rider letter service. They did the same at Mombasa Fortress headquarters until early 1942. Cipher officers were formed largely from local recruits. The Nairobi office was almost entirely staffed by WTS personnel.

The equipment used by EA Signals consisted originally of two prototype No 11 wireless sets which had been sent out to East Africa for trials before the outbreak of the Second World War. They proved very suitable for East Africa, either on point-to-point communications, or for mobile use. However, it seemed unlikely that supplies of these sets would arrive from the UK if war broke out. Consequently, authority was obtained to buy American wireless components for the construction by KAR Signals in Nairobi of a number of short-wave wireless sets. The two types used were long-range LR1 and LR2. They were for point-to-point communication over ranges of 300 to 400 miles (480 to 640km), and were capable of operating from either mains or a car battery/rotary converter. When built, these sets were taken into use in the Northern Brigade KAR area of Kenya in place of the old static medium wave Marconi sets which could only be worked at certain times of the day owing to atmospheric conditions.

Short range SR1 sets were built for mobile use over ranges of up to 150 miles (240km) operating from either dry batteries or car battery/vibrator converters. These sets were issued to 21 and 25 (EA) Brigades and were fitted into wireless tenders. Eventually supplies of wireless sets No 11 arrived from the UK and replaced the locally-made sets. A number of sets were made available by the South African Corps of Signals for long-range communications between Command HQ at Nairobi, Advance HQ which followed 11 (EA) Division closely through Somaliland and into Abyssinia, and the two Divisional HQs 11 and 12 (EA) Divisions. Several of the brigades which had to communicate over extreme ranges were also supplied with rear-link sets. These sets were designated as 16E and 18M, and were originally manufactured in the USA for the ham radio market.

The KAR battalions were equipped with VHF wireless sets produced commercially in the UK. They had been ordered in 1938. They were dry-battery-operated and easily man-packable, but were not very robust. They were later replaced by standard British wireless sets such as the No 38. The Windom aerial was used for working over long ranges. It consisted of a specially cut length of stranded copper wire strung between poles, with a down-lead to the set carefully tapped off at a predetermined point.

Another source of equipment was the large amount of Italian communications material captured at Addis Ababa. This included several 800 Watt transmitters. There was so much equipment that a signal park was specially formed to sort, check, and list it all. One unusual situation occurred following the capture of Addis Ababa and the cessation of hostilities. A high-powered radio was discovered in Harar. It was still working daily, direct to the Vatican. After visiting this radio terminal and talking to the operators-who belonged, with their equipment, to the Vatican - the CSO decided to allow them to continue with their daily schedules. At the same time, covert steps were taken to monitor their transmissions to check there were no breaches of security.

Although radio was used extensively in East Africa because of the distances involved, telephone lines were used over shorter distances. Overhead telephone lines, known as airlines, suffered from damage caused by giraffes running through them. Raising the height helped solve that problem.

The insignia of the KAR signal sections was a brass Kings African Rifles hat badge with crossed flags in the centre. A black flash was worn behind the badge by the Northern Brigade Signal Section and a red flash by the Southern Brigade Signal Section. A similar cap badge was planned for EA Signals with the change of title from King's African Rifles to East Africa Signal Corps. There is some doubt that this was ever produced. A brass shoulder title 'EA SIGNALS' was issued. Officers of EA Signals wore the cap badge of their parent corps or regiment.

At the end of the Second World War, the large East Africa Signal Corps was demobilised. Signalling remained within the KAR Battalion's Signal Platoons, and the East Africa Command Signal Squadron (EACSS) which was at Killarny Camp near Kibera village, Nairobi. The squadron included a Northern Area Troop at Nanyuki and a Southern Area Troop at Moshi. Until about 1947/48 it had been in Hargeisa with its HQ, which was withdrawn from Somali land to create Southern Brigade HQ at Dar-es-Salaam. A Signals Training Centre (STC) was located at Nyeri.

Women of the East African Women's Territorial Service (WTS) train as stretcher-bearers.

(Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

Separate from the squadron were two signal detachments. One was located at Hargeisa and the other at Mogadishu. The headquarters for the Chief Signals Officer East Africa Command was at Waterworks Camp in Nairobi. The composition of the squadron and detachments was two-thirds African and one-third British. Signals were recognised by a light blue, dark blue, green flash worn on the slouch hat and Royal Signals garter flashes on the khaki socks. Khaki drill bush jackets were worn with khaki drill shorts. The African soldiers wore shirts of Agola drab (grey in colour) and for ceremonial occasions wore bush jackets.

During the early 1950s, the responsibility of the squadron was split between providing command communications, and communications for the East African forces. Concurrent with the EACSS were 39 Independent Infantry Brigade Signal Troop, 49 Independent Infantry Brigade Signal Troop and 70 (EA) Infantry Brigade Signal Troop. Later that decade, circa 1959, they converted to 1 (KAR) Signal Squadron. In effect, it was the command signal squadron with a duel responsibility to the GOC EA Command and Commander 70 Infantry Brigade KAR.

The squadron was located at Buller Camp on the Ngong road. It ran the command radio network and provided a signals centre and crypto office at the headquarters at Waterworks Camp. It also provided a signals troop for HQ 70 Infantry Brigade at Nanyuki. Further to this, the squadron trained all the regimental signallers for the KAR battalions at the STC.

Before Independence, the size of the squadron was ten British officers, thirty British other ranks and 250 African ranks. Royal Signals also had various signals units in East Africa after the Second World War until Independence. When independence was granted to Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika in the early 1960s, their respective signals corps were created from their component of the 1 KAR Signal Squadron and the four KAR Battalions Signal Platoons at Dar, Jinjia, Gilgil and Nanyuki.

Black signallers of the King's African Rifles learn to signal the morse code with a single flag.

(Photo: SANNMH, T 6503).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PRIMARY SOURCES

Documents

East Africa Force Army List No 6 November 1940 - February 1941 (Nairobi Govt Printer, 1941). Imperial War Museum Department of Printed Books. Various papers including unpublished short history. Extracts from an article on KAR Signals (pre-1939) by Brigadier C H Stoneley 'Wireless Interception in the East Africa Campaign 1914-1916', Draft of article by A T Matson, Rhodes House Library, Oxford, 1969.

Correspondence

Imperial War Museum, Kenya National Archives, Rhodes House Library, Royal Signals Museum, Mr J Cumming, Capt C W Catt, Major P D Legge, Major D E Robathan, Major P J W Stephens, Brigadier C H Stoneley, Lt Col J J H Swallow, Capt W J Thomas.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Magazines/Newspapers

Jimmy, the Magazine of the Royal Corps of Signals in the Middle East. Various articles: 'The WTS Signal Section - Kenya'; 'Introducing a "GoGetter" Col C E Sketch'; 'Jambo Bwana' by Major D E Robathan.

Signals Vital Link.

East African Standard, 3 July and 10 July 1942.

Books

Campbell, G, The Charging Buffalo, Leo Cooper.

Moyse-Bartlett, H, History of the Kings African Rifles, Gale & Poulden, Aldershot, 1956.

Nalder, R F H, The Royal Corps of Signals (Royal Signals Institution, London, 1958).

Our Saga 1939-45 Womens Territorial Service FANY.

Page, M, A History of the King's African Rifles & East African Forces (Leo Cooper, Trowbridge, 1998).

Suid-Afrikaanse Sein Korps/South African Corps of Signals (Documentasiediens SAW, Publikasie Nr 4, Pretoria, 1975).

Thomas, T, Signal Success (The Book Guild, Lewes, 1995).

Warner, P, The Vital Link - The Story of Royal Signals 1945-1985 (Leo Cooper, London, 1989).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org