The South African

The South African

(Based on an assignment submitted to the Department of History, UNlSA 2001.)

by Allan Sinclair, Curator of Art,

SA National Museum of Military History

Oral history sources are, in Jan Vansina's opinion, documents of the present, because they are delivered in the present. At the same time, however, they are also voices of the past, because their message is about the past (Vansina, 1965, Preface). Whether comprised of recollections from people interviewed in a literate society or the traditions of a pre-literate society handed down over several generations, oral sources are seen as the voices of those not heard through conventional media of historical research, in other words, in written form. Oral history enables ordinary people to have a place in history as well as to assist in the creation of historical awareness (Tosh, 1987, pp 206-7).

In the history of the literate world, those who had the opportunity to record their messages and facts on paper were able to do so. But what of those who were not in that position? Many people in literate societies were illiterate and remain so, even today. Others lacked the time or confidence to write, while still others were very reluctant to impart their knowledge. Lynda von den Steinen, a masters student at the University of Cape Town who undertook a thesis on the oral reminiscence of the rank and file of Umkhonto-weSiswe (MK), discovered this reluctance among many exsoldiers of MK. Some distrusted the reasons for the interview, others feared that their revelations could bring retribution on themselves, and yet others simply wished to forget that area of their lives (vd Steinen, 1999, pp 1,3).

When focusing on military history, oral sources become very important in providing information on the ordinary soldier, sailor or airman, who experienced most aspects of warfare at first hand and who revealed very different perspectives about warfare from those of their commanders and politicians. In both South Africa and the United Kingdom, these initiatives have, for many, come too late. There are no veterans left who fought in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), those who fought in the First World War (1914-1918) now number only a handful, and even the veterans who fought in the Second World War (1939-1945) are rapidly becoming fewer and fewer (Van den Steinen, 1999, p 2).

During the 1970s, a student of California State University was given the task of locating and interviewing a veteran of the Anglo-Boer War. She eventually located British veteran, Warrant Officer W F Avery, at the Royal Hospital Chelsea. Avery proved very alert and remembered much detail for a man then in his early nineties. His opinions during the interview suggested that the war had largely influenced the rest of his life. His attitude towards the war, his impressions of the British commanders and politicians, as well as the causes of the war, were very outspoken and articulate (vd Steinen, 1999, pp 4, 17).

In the past, most written sources were produced from a Western adult male perspective; women, children, labourers, the poor and immigrants enjoyed less access to recording their data on paper (Tosh, 1987, p 210). This scenario also applied to South Africa. In the 1980s, the South African National Museum of Military History initiated a programme of gathering oral history and in 1998, while studying towards a post-graduate disploma in Museology at the University of Pretoria, Pearl Nkuna and Rowena Wilkinson completed an oral history assignment which indicated that two important aspects of the country's written history of the Second World War reflected largely a white male point of view. These two areas were the role of women, especially in the entertainment field, and the role of black soldiers who served with the South African forces (Wilkinson, 1998, p 13; Nkuna, 1998, p 3).

Muff Evans and Merle Calsworthy, who served in the entertainment unit during the Second World War,

were interviewed by librarian Rowena Wilkinson in the Museum library in 1998. (Photo: SANMMH).

Librarian Rowena Wilkinson interviewed two women, Miss Muff Evans and Mrs Merle Galsworthy, who had served with the Union Defence Forces' Entertainment Unit during the Second World War. The women veterans proved to be both informative and articulate and they enjoyed the experience, expressing their satisfaction that they had contributed knowledge that would otherwise have been denied to future generations. The interviewees were also afforded an opportunity in which to express their great disappointment that a history of the unit in question had yet to be published and the Museum felt very fortunate to uncover a much neglected part of South Africa's military heritage (R Wilkinson, Interview with M Evans and M Galsworthy, 1998).

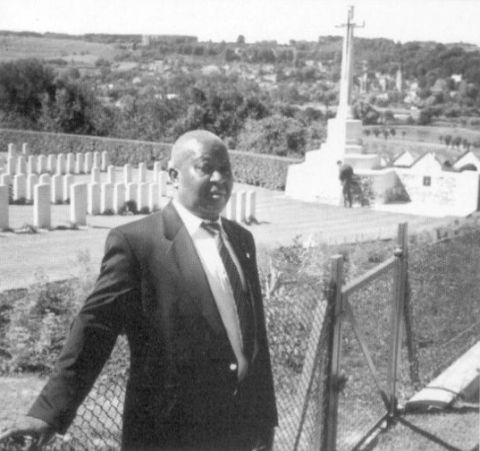

The second interview was undertaken by Education Officer Pearl Nkuna with Mr Freddie Nkoma, who had served with the South African Native Military Corps during the same war. This veteran, too, felt honoured to be interviewed on his experiences during his period of service and to have his personal accounts preserved in the Museum's archives. During this interview, another interesting facet to oral history collecting emerged, as the interviewer, as a young black woman, felt restricted by cultural norms from questioning Nkoma, as an elderly black man, in certain matters. For example, owing to both her gender and age, she felt it inappropriate to ask him to divulge certain information such as contact with women in North Africa, (N Nkuna, Interview with F Nkoma, 1998).

Military veteran Freddie Nkoma, seen here visiting the Arques-la-Bataille military cemetery in France,

where black South Africans who died in the First World War lie buried. Mr Nkomo related his own war-time

experiences as a member of the Native Military Corps in the Second World War to Nosipho Pearl Nkuna

during an interview held in 1998. (Photo: By courtesy, SANMMH).

The Museum's oral history programme also unearthed personal accounts of significant events that had taken place during the Second World War. One such event was the famous Great Escape which occurred at Stalag Luft 11/ in Silesia in 1943, when about 76 Allied air force officers, led by South African-born Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, attempted to break out through a tunnel dug underneath the camp. Only three managed to make it back to safety. The rest were recaptured and, of these, fifty, including Bushell, were executed by the Gestapo, apparently under the orders of Hitler himself (Popple, 1995, pp 15-25; File 920 Plunkett DL). In 1991, Hamish Paterson, the Museum's curator of uniforms, interviewed Mr Desmond Plunkett, thirteenth to escape from the tunnel. Mr Plunkett, a Royal Air Force pilot and instructor, had been on a mission over Germany in June 1942 when his aircraft was shot down. He was captured and sent to the Stalag in question. There he became involved in the planning of the escape and was given the task of producing 1 000 maps with the aid of a mimeograph. Mr Plunkett recalled how, after his escape, he managed to evade capture for two weeks before being recaptured in Czechoslovakia, only because his forged documents had expired. Fortunately, he was not amongst the 50 who were shot and was later able to relate his experiences (H Paterson, Interview with D Plunkett, 1991 ).

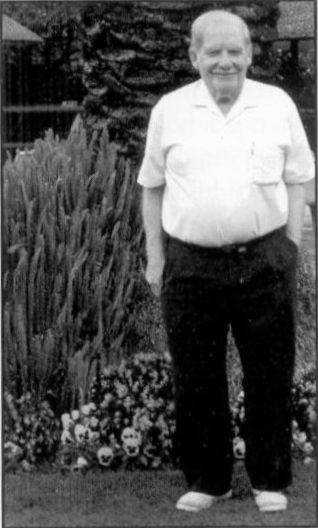

Mr Des Plunkett, an ex-air force officer of the Second World War, had a fascinating story to tell

of his experience of the Great Escape at Stalag Luft III, Silesia, in 1943.

He was interviewed in 1991 by the Museum's Curator of Uniforms, Hamish Paterson. (Photo: SANMMH).

From the above, it is clear that oral sources allow the ordinary person to express his or her views and to have a hand in creating historical awareness. These sources add extensively to historical knowledge already preserved and may represent the only recordings of information which would otherwise be temporary at best and simply unattainable at worst. Oral sources also contribute greatly to the human aspect of history (vd Steinen, 1999, p 2; Wilkinson, 1998, p 1). However, oral sources used in military history do have their limitations, causing historians to question the reliability of these sources in view of such problems as fading or selective memory, deliberate embellishments, self-aggrandizement, and a reluctance to associate others, or even themselves with particular events (vd Steinen, 1999, p 2). Thus, there may be serious discrepancies in the evidence obtained from oral sources and the solution is to evaluate the content carefully and to use this information along with other sources (Tosh, 1987, p 215). However, it should also be remembered that similar discrepancies can arise in written sources as well. In view of this, while oral sources used in military history cannot immediately furnish neglected areas with verified information and should be critically analysed, their importance as sources needs to be evaluated alongside other, written, sources (Tosh, 1987, p 227).

In conclusion, oral sources have an important role to play in the collection of historical evidence. Oral history serves as a means of transmitting and preserving the voices of those who, for a number of reasons, have not been heard in conventional written sources. In evaluating the use of various sources in the study of military history, it seems clear that the contribution made by oral sources cannot be ignored. In order to make the most of oral sources, however, historians need to recognise and be aware of the limitations of these sources. One might ask whether history can ever present a complete story without the use of oral sources.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Documents

'File 920 - Plunkett D L' (Archives of the SA National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg).

Nkuna, N, 'Oral history recording, presentation, and documentation' (unpublished assignment completed for the Postgraduate Diploma in Museology, University of Pretoria, 1998, a copy of which is held at the SA National Museum of Military History).

Von Steinen, K, and von Steinen, L, 'One soldier's war - The Anglo-Boer War reminiscences of William Frederick Avery, RAMC' (Paper delivered at The Anglo-Boer War - A Reappraisal Conference, held at the University of the Orange Free State, 1999).

R Wilkinson, 'Collecting oral history' (unpublished assignment completed for the Postgraduate Diploma in Museology, University of Pretoria, 1998, a copy of which is held at the SA National Museum of Military History).

Interviews

Oral History Collection, Tape 193, 1998: Miss M Evans and Mrs M Galsworthy, Second World War, UDF Entertainment Unit, conducted by R Wilkinson (Archives of the SA National Museum of Military History).

Oral History Collection, Tape 192, 1998: Mr F Nkoma, Second World War, Native Military Corps, conducted by N Nkuna (Archives of the SA National Museum of Military History).

Oral History Collection, Tapes 138-9, 1991: Mr D Plunkett, Second World War, Royal Air Force, conducted by H Paterson (Archives of the SA National Museum of Military History).

Published works

Popple, T, 'The Wooden Horse: The Great Escape' in After the Battle, No 87, 1995, pp 15-25.

Thompson, P R, The voice of the past - Oral history (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1978).

Tosh, J, The pursuit of history - Aims, methods, and new directions in the study of modern history (Longman, London, 1987).

Vansina, J, Oral tradition as history (London, 1965).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org