The South African

The South African

In 1906, following the Anglo-Boer War, the Colony of Natal was plunged into rebellion when several tribes refused to pay a Poll Tax that was introduced by the Colonial Government, headed by Prime Minister The Hon Charles Smythe, to help reimburse the somewhat depleted Treasury.

There were, of course, several other factors that contributed towards the uprising, and these are dealt with in the writer's earlier article, 'The Bambata Rebellion of 1906: Nkandla Operations and the Battle of Mome Gorge', published in Military History Journal Vol 8, No 1, June 1989.

One of the amakhosi (chiefs) who had thrown his weight behind the resistance to the payment of the Poll Tax was Bhambatha Zondi (also spelt Bambata). Bhambatha, son of Mancinza Zondi, was born in the Mpanza Valley between Greytown and Keate's Drift, KwaZulu-Natal, in about 1865. A somewhat controversial character, he had been convicted on several occasions for debt, cattle theft and, early in 1906, for participating in a faction fight (which is a regular occurrence in that area even today).

When the time came to pay the tax on 22 February 1906, Bhambatha was faced with a dilemma; he was apparently prepared to pay, but one of his indunas (Nhlonhlo) informed him that the majority of the tribe refused to do so, and would resort to armed resistance if necessary. The magistrate in Greytown, Mr Cross, received a report informing him that he would be killed if he went to Mpanza, so he instructed Bhambatha to travel to Greytown.

On 22 February, the tribal elders arrived in Greytown while Bhambatha remained in a wattle plantation overlooking the town, apparently trying to persuade Nhlonhlo to change his mind, but, according to the elders, he was suffering from a stomach ailment (which could have been a case of 'butterfly nerves', which we have all experienced in difficult circumstances).

Dawn, Sunday, 10 June 1906, showing the position of

the forces surrounding the rebels in the Mome River Gorge.

(Source: From a sketch on the spot by a TMR officer,

Transvaal Leader weekly Edition, 23 June 1906).

The result was that Bhambatha was deposed as inkosi of the amaZondi, and he fled to the Usuthu umuzi (homestead) of King Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo. According to Bhambatha's wife, Siyekiwe, King Dinuzulu ordered Bhambatha to return to Natal and carry out an act of rebellion, a claim that was subsequently vehemently denied by the King at his trial.

Bhambatha then readied his tribesmen for combat. His inyanga (war doctor), Malaza, prepared some muthi (medicine) at an umuzi on the late Mr George Buntting's farm, Fugitive's Drift. (The writer was taken to this site by the late Mr Buntting, who farmed in the area for many years. According to tradition, body parts of a child were used in the recipe, resulting in immunity to the white men's bullets (which would turn into water). The site of this umuzi is quite close to Mzinyathi Cottage on Mr David Rattray's farm, Fugitive's Drift.)

On the first occasion that the muthi was put to the test, the action at Mpanza on 4 April 1906, none of the Rebels was killed or wounded, lending credence to Malaza's claim. Four members of the Colonial forces were killed (Troopers A H Aston and J P Greenwood, and Sergeants E T N Brown and J C G Harrison) and three were wounded (Troopers Braull, Dove and Emanuel). Those killed were buried on the farm, Burrups between Mpanza and Greytown. This action resulted in Bhamhatha and the amaZondi hecoming totally involved in the uprising and his name being given to the Rebellion.

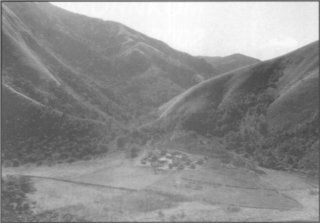

Mome Gorge, August 1985, showing the entrance to

the gorge and the site of the rebels' camp.

(Photo: By courtesy, Ken Gillings).

The back of the 'Bambata Rebellion' was broken on 10 June 1906 in the Battle of Mome Gorge, in the heart of the Nkandla area of Zululand. According to official sources, Bhamhatha was killed while walking up the Mome stream (Stuart, 1913, p 310). Shortly before the shelling of the Dobo Forest by the Natal Field Artillery, a 'native levy' on the left bank of the Mome noticed a solitary unarmed rebel making his way upstream, walking in the water. On the right hank, just behind the rebel, was another 'levy'. The rebel left the water to move along the right bank having observed the former 'levy', but not the latter. The latter, then on the same bank as the rebel, thrust his spear into the rebel with such force that the blade was bent and could not be removed. The rebel collapsed and the 'levy' was joined by the other, who raised his spear to finish off the victim. Then the rebel suddenly grabbed the spear with both hands and tried to wrest it from his grasp. Both 'levies' were attempting to overpower the rehel when a member of the Nongqayi (the Natal Native Police) arrived and shot him in the head.

It was only on 13 June - three days after the battle - that a party under Sgt Calverley was sent back into the gorge to obtain proof of Bhambatha's death. This same rebel's hody was found, already in an initial stage of decomposition, and identified as that of Bhambatha. The head was removed, placed in a saddlehag and taken to Nkandla, where it was identified. Official reports emphasise the respect shown for the head, and only a selected few were permitted to view it.

Identification in the gorge was based upon a description of Bhamhatha's features beforehand - a gap between the two middle upper teeth; a slight beard rather under than in front of the chin; a scar immediately below one eye and another on the cheek opposite; a high instep. According to Capt J Stuart, these features were confirmed by the two Zulu informants at Nkandla, and also by two of Inkosi Sigananda Shezi's tribesmen, as well a prisoner who had linked up with Bhambatha. All confirmed that it was Bhambatha's head (Stuart, 1913, p 117).

Walter Bosman describes the death and identification

of Bhamhatha in The Natal Rebellion of 1906

(1907, p 103):

The Battle of Mome Gorge, Sunday, 10 June 1906.

(Source: Transvaal Leader Weekly Edition, l6 June 1906).

The Battle of Mome Gorge: Scene on the Nek.

(Photo: By courtesy, Killie Campbell Africana Library).

Capt Bosman, who was aide-de-camp to Col Mckenzie, defends

the decapitation of the rebel (1907, p 107):

Bosman further states (1907, p 108) that 'Col

McKenzie caused the head to be taken back to the

Mome bush and placed with the body, which was

recently interred on the right bank of the Mome

stream,' Interestingly, however, on page 539 of The

Nongqai magazine, a photograph depicts a skull

mounted on a raised and polished shield with the

caption:

Devitt goes on to state (1937, p 71) that Maj Platt, with some 200 mounted men and the 'gruesome pickup', returned to the gorge. With the aid of half a dozen assistants, the corpse was interned in a hastily dug grave.

Despite the convincing arguments that

Bhambatha was killed, doubts still linger in the minds

of many. The late Mr C T Binns, a highly respected

Natal historian, sows the seed of doubt in his

magnificent hook entitled Dinuzulu - The Death of the

House of Shaka (Longmans, London, 1968).

Appendix iX is headed 'Was Bambata killed in the Mome

Gorge?' Binns wrote:

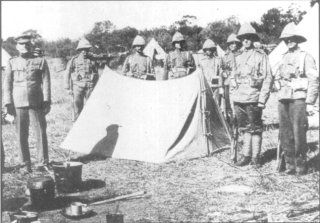

Men of the Durban Light Infantry stand guard over Bhambatha's body.

(Photo: Transvaal Leader Weekly Edition, 30 June 1906).

Binns interviewed a Zulu named Joseph Nzama in

Pietermaritzburg, who had been asked to identify

Bhambatha's head. He states (Binns, 1968, p279):

During frequent visits to Mome Gorge, the writer has also tried to locate Bhambatha's grave. After a great deal of persuasion, he was privileged to have been taken to where the skeletal remains of Mehlokazulu kaSihayo lie untouched and unburied. (Mehlokazulu was a son of Sihayo kaXongo, whose unfaithful wife had fled into Natal from Zululand. Mehlokazulu was one of three sons who pursued the woman in one of the incidents which sparked the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879). Appeals for assistance in viewing the grave of Bhambatha, however, have always met with the same response: 'Bhambatha does not lie buried here.' A late friend of the writer, the former custodian of King Cetshwayo kaMpande's grave, Mr Jotham Shezi, was emphatic that Bhamhatha 'escaped to the Portuguese' (Lourenço Marques/Maputo). Mr Alpheus Zondi, the Chairman of the Zondi Tribal Community, who lives in the Ngome/Keate's Drift area of KwaZulu-Natal, is adamant that Bhambatha fled to Mozambique. He told the writer that when Calverley was accompanied by the 'three native spies' referred to earlier in this article, they falsely identified a body bearing a likeness to Bhambatha as his. This man was Sishukane Zondi, mentioned in Bosman's book as 'Satushukane'. Mr Zondi told the writer that the party had been exhausted after the strenuous descent into the gorge, and half-heartedly identified the decomposing body as that of Bhambatha.

James Stuart, whose account of the Rebellion and

archival collection are invaluahle works of reference,

interviewed several veterans. One was Mjobo

kaDumela whom he met on 26 January 1912 in

Pietermaritzhurg. Mjobo was a retainer of Mr A S

Windham, a former Natal magistrate. The following

is a direct translation of his statement (given in Zulu)

in the James Stuart Archive, Vol 3. p 142:

Then, on 9 February 2002, the writer received an e-mail from Mrs Linda Atkins of Ashorne Hill Management College, Leamington Spa, in Warwickshire, UK. An old trunk belonging to a Lt Col John Howard Alexander DSO MC had been discovered in the attic. Col Alexander was born in Dublin in 1880. His military records indicated that he had served in the Royal Engineers and had been awarded his Military Cross on 26 June 1916, and his Distinguished Service Order on 4 January 1919. He had been Mentioned in Despatches on four occasions - on 31 May 1916, 29 September 1916, 6 July 1917 and 12 January 1918. In 1918, he was Deputy Controller of Baghdad Railway. Apparently, Col Alexander managed Ashorne Hill during the Second World War for the British Iron and Steel Confederation when the Staff was evacuated from London. His American wife was in charge of the catering and housekeeping. The colonel's records also indicated that he had served as a temporary major (substantive captain) in the Union Defence Force in 1912, and that he was fluent in English, isiZulu and French. Mrs Atkins also found a letter addressed to him as Maj J H Alexander, Royal Engineers CRE Anzac Mounted Division. His role in South Africa has still to be researched, but there are spears mounted on the wall in the Great Hall of the Conference Centre at Ashorne Hill which indicate that he must have played a role in Natal at some stage of his career.

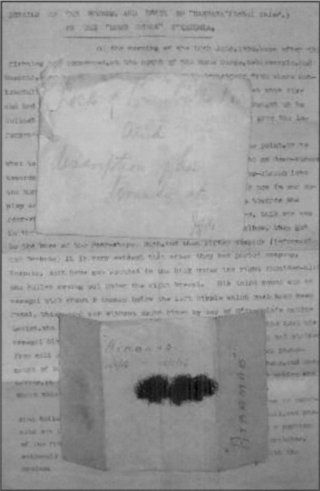

The recent find - Envelopes, lock of hair and

typed report found in an English attic.

(Photo; By courtesy, K Gillings).

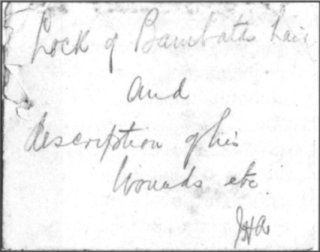

The trunk contained numerous papers, newspaper cuttings, photographs and negatives. One envelope proved to be of special interest to the writer, however. Written on the cover were the words: 'Lock of Bambata's hair and description of his wounds etc.' On opening the envelope, another, similar in size but folded in three, was discovered, marked: 'ATABMAB 10/6/06 - 18/6/06'. 'Atabmab' is, of course, 'Bambata' spelt backwards! It contains a lock of African hair with a few pieces of grass entwined. The typed report is included here.

The envelope containing the new find.

(Photo: By courtesy, K Gillings).

The envelope found in the attic,

marked 'ATABMAB', 'Bambata' in reverse.

(Photo: By courtesy, K Gillings).

The description of events in the Mome Gorge in the typed report shown above is extremely convincing, especially regarding the fate of this remarkable Zulu who gave his name to an uprising that is considered by many Black people of South Africa as the first example of a determined and reasonably successful call to arms to oppose the (White) authority's imposition of an unpopular law upon what was considered to have been an oppressed nation.

Whatever the true fate of Bhamhatha may have been, the discovery of the evidence in the attic revives an interesting debate about what is undoubtedly a very sad chapter in KwaZulu-Natal's history; an event the centenary of which is soon to be commemorated by the Black people of the province. It will be referred to by the amaZondi as 'The 1906 Protest', following a decision taken by the amaZondi at a meeting of the 1906 Protest Centenary Committee, Pietermaritzburg, on Friday, 22 March 2002.

The envelope containing the lock of hair was brought back to KwaZulu-Natal by the writer's son, Douglas, on his return from the United Kingdom in 2002, and will be presented to an appropriate repository for safekeeping in due course.

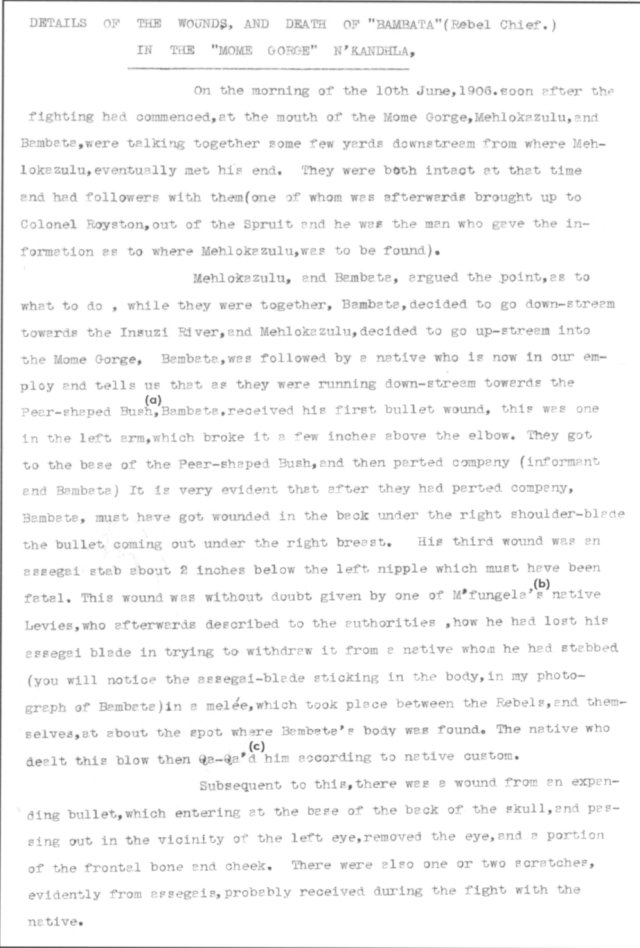

Above: Typed report, detailing the nature of the

wounds which caused the death of Bhambatha

Zondi. Notes added by the writer.

(By courtesy, Ken Gillings).

Notes:

a. The 'Pear-shaped Bush' is the Dobo Forest, near the entrance to the Mome Gorge.

b. Mfungelwa was an influential Inkosi from Zululand who committed his tribe to the

Colonial authorities.

c. This involved slitting one's victim from groin to sternum to enable the spirit to escape,

failing which it was believed that the instigator would experience a swelling of the stomach,

similar to the victim.

The text of the typed report is repeated below for clarity:

Mehlokazulu, and Bambata, argued the point, as to what to do , while they were together, Bambata, decided to go down-stream towards the Insuzi River, and Mehlokazulu decided to go up-stream into the Mome Gorge, Bambata, was followed by a native who is now in our employ and tells us that as they were running down-stream towards the Pear-shaped Bush[a],Bambata, received his first bullet wound, this was one in the left arm, which broke it a few inches above the elbow. They got to the base of the Pear-shaped Bush, and then parted company (informant and Bambata) It is very evident that after they had parted company, Bambata must have got wounded in the back under the right shoulder-blade, the bullet coming out under the right breast. His third wound was an assegai stab about 2 inches below the left nipple which must have been fatal. This wound was without doubt given by one of M'fungela's[b] native Levies, who afterwards described to the authorities, how he had lost his assegai blade in trying to withdraw it from a native whom he had stabbed (you will notice the assegai-blade sticking in the body, in my photo graph of Bambata)in a melée,which took place between the Rebels, and themselves, at about the spot where Bambata's body was found. The native who deal this blow then Qa-Qa'd[c] him according to native custom.

Subsequent to this, there was a wound from an expending bullet, which entering at the base of the back of the skull, and passing out of the vicinity of the left eye, removed the eye, and a portion of the frontal bone and cheek. There were also one or two scratches, evidently from assegais, probably received during the fight with the native.

Binns, C T, Dinuzulu - The death of the House of Shaka (Longmans, London, 1968).

Bosman, W, The Natal Rebellion of 1906 (Longmans, Green & Co, London, 1907).

Devitt, N, Galloping Jack - Being the Reminiscences of Brigadier General John Robinson

Royston, CMG DSO VD, of Natal, South Africa (H F & G Witherby Ltd, London, C 1937).

Stuart, J, The History of the Zulu Rebellion 1906 (Macmillan, London, 1913).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org