The South African

The South African

Selby (Sam) Webster served in various units during the Second World War, starting off as a sapper in the Engineers in 1940 and ending the war as a captain in 1945. In 1944, he was seconded to the British Army and served with the Black Watch in Italy and Greece. He was a member of the South African Permanent Force between 1946 and 1951. He was a founder member of the Military History Society on the East Rand about 10 years ago.

End of Box.

Prologue

On the night of 20 August 1945, at a place near Cairo called Helwan, soldiers of the Union Defence Force (UDF) became a 'mob' and went on a rampage. They smashed, looted and set fire to cinemas, stores, cars, and much more. Damage done that night was officially estimated to amount to more than £ 22 million. All the men involved had seen 'Active Service' with the UDF as volunteers. (There was no conscription in South Africa - every man went to war voluntarily). What happened there that night hecame an 'open secret'. All reports in the media were censored and no mention was made in the press. (Strangely enough, no mention of it is made in any book dealing with the history of the South African Forces during the Second World War).

The night in Helwan was an open secret because, as these men came home, they told their fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, and anyhody else all ahout it. Even today, youunger people who have heard their fathers and grandfathers talk are asking where is this place called Helwan? What happened there and why did it happen? This then is an attempt, after 56 years, to bring the matter into the open.

Incidentally, in the opinion of some observers, what happened in Helwan on the night of 20 August 1945 was one of the factors which led to the defeat of the United Party in the 1940 election. Many ex-servicemen either abstained from voting, or voted for the National Party.

A 'home' base in Egypt

In 1941, with the war in Abyssinia drawing to a close, the UDF

authorities realised that if South Africa was to take art in the war in

the Western Desert, they would need to establish a Reserve and

Transit (R&D) depot in Egypt, and asked the British to arrange

accommodation for this. However, they were warned to accept

humbly whatever was offered as they did not want to disturb

relations with Egypt because of the delicate situation Surrounding the

security of the Suez Canal. The ground offered was at Helwan - a

desolate expanse of desert south of Cairo - and on 19 May 1941, a

survey company from the South African Engineer Corps (sappers)

arrived and started to draw up plans to lay out the proposed R & T

depot, along with a 600-bed hospital. The plans appeared to be

based on the following:

- The housing of not more than 5 000 men at any one time;

- The buildings were to be in 20 blocks, each to cater for about

250 men, plus one block for administration;

- These blocks were to be spread out, and each block

should, as far as possible, be self-contained in case of air raids.

It should he noted that the master plan made no provision for naval or air force personnel, who would make their own arrangements to get their men home.

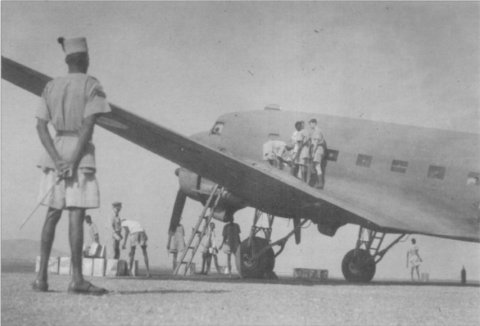

Ex-POWs arrive in the Middle East to await transportation to their

temporary home before being repatriated to South Africa. This group

consisted of some 400 escapees. (Photo: SANMMH, E 0525)

To start with, the building operations were let out 'on contract', but it was soon realised that this was not a satisfactory arrangement and the contract was cancelled. Work was then taken over by the sappers, who were fortunate in that during building operations they were able to use the facilities of the New Zealanders, who already had a similar depot at Maadi right next door to them.

The official title of the base was No 1 R&T Depot, but it was never known by this name. To the South African soldier, it was only known as Helwan.

With the arrival of the UDF from East Africa, the South African Air Force (SAAF) instituted a shuttle service between South Africa and Cairo using Ventura and DC 3 (Dak) aircraft. This service, consisting of three or four planes a day, was to ferry reserves and mail from South Africa to Cairo, and to transport the sick, wounded and compassionate-leave cases back to the Union. The shuttle service involved three overnight stops between Cairo and South Africa and at some places morning stops were made for fuel and a cup of tea, very often supplied by the local women as their contribution to the war effort.

The Helwan Depot and the shuttle service were a tremendous success, so much so that, when the 6th South African Armoured Division (6th SAAD) became involved in the Italian Campaign, a similar depot was established at Foggia and the shuttle was extended accordingly. Up to the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, the UDF could boast that no man was held at one of these depots for more than two or three days. But the bubble was about to burst.

The end of the war

By the beginning of April 1945, it had become obvious that the war was fast coming to a close and that Germany would be defeated. The 6th SA Armoured Division was very much involved ini the steady push towards Austria and Germany as part of the 5th Army. Every member of the division, as well as the many other South African troops doing service as divisional, corps or army troops (such as the engineers, artillery, and seconded officers), all had only one ambition - that their luck would hold out so that they could see out the end of the war. They had volunteered to fight a war against Fascism and had no intention of being used as occupational troops, a task which, in their opinion, could be left to the Americans and the British. The South Africans felt that there was enough trouble brewing at home with the activities of the anti-war group, the Ossewa-Brandwag (OB).

On 1 May, the UDF suddenly woke up to the fact that the war in Europe was drawing to a close - VE (Victory in Europe) Day was on 8 May - and that no plans had yet been made to get all their men home. The Director-General SAAF was required to find a solution to this problem. On his instructions, Nos 1 and 5 wings of the SAAF were brought together to form No 4 Group. This group, flying Dakota and Ventura aircraft, was to be used in an ITS - Intensified Transport Service/Shuttle Service. The plan was to move 5 000 troops a month by air, starting on 1 July 1945. About 15 000 men were to be transported home by sea during the second half of the year, resulting, hopefully, in the repatriation of 45 000 troops by the end of the year.

Responsibility for working out the logistics of putting the repatriation plan into operation was passed to the officer commanding the newly formed No 4 Group. The shuttle service, which had been in operation since the UDF had arrived in the desert, was only using three or four aircraft a day. For the proposed ITS scheme, however, it was estimated that at least ten Dakotas, each carrying 24 passengers, and fifteen Venturas with 13 passengers each would be required, a total of 25 aircraft a day. The OC of No 4 Group was therefore required to set off on a reconnaissance up and down the length of Africa, from Cairo to Pretoria, to arrange for airfields, accommodation and fuel so that the scheme could be brought into operation. This scheme, like so many military plans, was the brain child of the back room boys, who then expected the troops on the ground to put it into operation, (and carry the blame if it did not work). To make matters even worse, it was officially announced in The Springbok, the UDF newspaper, on 24 and 31 May that, as from 1 July, 500 men a day would be repatriated to the Union (RTU). This was physically impossible! Staging posts such as Kisuma, Jabora, Chingola, Juba, Kumala, Wadi Seidna and Khartoum would be expected to supply fuel for the aircraft, as well as food and accommodation for 500 men whenever their port was used as an overnight stop. It was also announced that a demobilisation scheme had been drawn up, basad on the date on which each individual had gone on full-time service. On paper, this seemed an excellent idea. Those who were first mobil ised for the war (Category A) - the 1st Brigade troops, for instance - would be the first to go home. Members of units that mobilised on 1 July 1940 were classified as Category C and this arrangement was happily accepted by the men. But, there was a snag. The troops due for demobilisation first had to make their way to Helwan, the starting point for the trip home.

An American-built Douglas troop-carrying aircraft, flown by a ferry

pilot of the South African Air Force, refuels at Tabora on the daily

Cairo-Pretoria Shuttle Service route. In favourable weather, the

journey down the length of the Africa was completed in 32 flying hours.

(Photo: By courtesy SANMMH, Ref No E0505)

Things go awry

Nothing can be found in print, nor was any statement ever issued, to explain the principles on which the 'demob' scheme was based. While it looked good on paper, it would seem that little or no thought had been given to the large number of men who were not part of the 6th SA Armoured Division. To start with, there were the thousands of recently released POWs, men who had 'been in the bag' since the Sidi Rezegh and Tobruk battles in the desert. Their return home was a top priority.

The Springbok was circulated to all South Africans, including those who were not part of the 6th Division and, as a result, all South Africans were aware of the official statements made regarding the demob scheme. When shown the announcements, the South Africans' senior commanders, mainly British, expressed their gratitude for the work done by them and immediately put transport and drivers at their disposal to get them to the R & T Depot at Foggia. This depot was never intended to hold large numbers of men and soon became overcrowded, and attempts were made to turn them away. This applied particularly to those who had not served with the 6th Division, the depot commander's attitude being: 'You served with the British Army. It is their job to get you home.' Being South Africans, many so affected used their initiative to 'hitch-hike' by sea and air from Italy to Egypt. They made their way to Helwan, where they were neither expected nor welcomed.

Like Foggia, the Helwan depot was soon overcrowded. Bungalows designed to take 25 men now had to accommodate 40 or 50. By 20 August, the depot designed to hold 5 000 men was found to be holding 9 000. An official announcement on 9 August stated that 3 000 to 5 000 men were expected to be repatriated by sea at the end of the month, but less than a week later on 15 August, it was further announced that the expected shipping had been delayed, and that further announcements would be made later.

Following the announcement on 9 August about shipping, the comniander of the Foggia depot had seized the opportunity to ease the congestirln in his camp by getting a draft of men aboard a ship to Egypt, and they were already on their way when the 15 August announcement was made. The arrival of these, by then unhappy men only served to increase the congestion at the Helwan depot. This led to long food queues in the camp and, owing to the shortage of trained master cooks, the depot staff were forced to hire Egyptians and the quality of the food declined. The matter was brought to the notice of the higher authorities, but little or nothing was done to relieve the situation. There were only eight master cooks available to serve thirteen messes when at least 22 were required.

The standard of discipline also deteriorated. As the men arrived at the depot, they were split up, firstly alphabetically according to surnames, and then according to their categories (A, B, C, etc) in the demobilisation scheme. This meant that they were thrown together with fellow soldiers and NCOs whom they did not know. The vast majority of the UDF's junior officers had come up through the ranks and had been accepted by the men as 'one of the boys'. When peace came, the men no longer referred to them by their rank, but by their first name and surname. They consequently took little note of orders given by officers and NCOs whom they did not know. With no duty officer or duty NCO going around the various messes to see if there were any complaints, the men felt that nobody was interested in them.

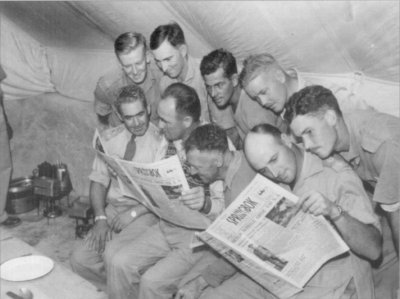

South African troops pore over the first edition of

their Springbok newspaper, printed in Cairo and

distributed free to the troops. (Photo: SANMMH, E292)

Morale dropped even further when, on 26 July, The Springbok carried a statement by the Director General of Demobilisation (DGD) that indicated that his organisation was unable to cope with the demobilisation situation at home. He called for 500 volunteers who would be taken home as a top priority to assist in the demobilisation process. This meant that the 500 so selected would be going home irrespective of their category. But morale really hit rock bottom when the men did not receive their copies of The Springhok of 2 August. All sorts of rumours - latrinograms - started to circulate that it had been suppressed because it had carried pictures of the true conditions in the camp.

The above appear to be the major causes of the drop in morale within the camp. The subsequent court of enquiry was to list at least another dozen minor complaints. However, there was another factor which was not listed, namely that, within the camp, all trading rights except those of NAAFI (Naval, Army and Air Force Institute), were controlled by Egyptians, and the men felt that they were not being given a fair deal by these traders. A serious problem arose over the cinemas when men who had bought tickets found that they were unable to get in. However, this trouble was caused largely by the men themselves. The cinemas were running six shows a day with the same film and were not cleared between shows. A man would buy a ticket and, once he was inside, would remain seated at the end of the film, staying on for the next show and the next, so that those waiting outside could not always get in. The same type of behaviour was evident at the various mess halls. Again, a soldier might be forced into a queue for about 30 minutes before he got food, only to find that there was no place for him to sit and eat because those who had already finished eating would remain seated, waiting for the next meal. 'There was just nothing to do', said one who was there, 'The men went to church on Sunday because it was something to do'. Unlike the British in the Caserta area, who arranged concert tours (ENSA), soccer, rugby, and many other events to keep their men awaiting demobilisation and repatriation occupied, the UDF arranged for only one rugby match -against the Kiwis - to break the boredom of sitting in camp awaiting transport to take them home. With 9 000 idle men hanging around, doing nothing, it was merely a question of time before something was going to happen, and there was nothing the depot commander could do aboui it.

One of a batch of ex-POW escapees, who arrived in Egypt from Italy

eagerly catches up on the latest news. (Photo: SANMMH)

The mob takes over

A few days prior to 20 August, it became generally known that a 'protest' meeting was to be held in the Dooley Briscoe Sports Ground on that date. By 19h00, a crowd of about 1 500 had gathered there and were addressed by various individuals, but did not seem to be under the control of any particular person. They soon became an unruly mob, howling at the speakers, particularly officers, and as the crowd increased in size, it became more violent. The stage was set for an explosion. There are two versions of how it started: The official one, favoured by the subsequent court of enquiry; and the other, as told by a witness who was there, but did not give evidence.

The official version

During the three days earlier, attempts had been made to set fire to the Pall Mall Cinema, privately owned by Egyptians. During the meeting of 20 August, at about 20h20, someone did manage to address the crowd and suggested that the meeting be held over for a while so that they could visit the cinemas and get all the troops out to join in the protest. The crowd apparently agreed to this, but as they dispersed, someone shouted, 'Let's burn the place down!' 'Yes', shouted the crowd and off they went.

The account of the witness

At the Pall Mall Cinema, a show was in progress when the projectors broke down, or the film may have snapped. After about five minutes, the audience became restless and started whistling and shouting. When nothing happened, somebody picked up a stone and threw it at the screen. Soon they all joined in. The mob at the sports ground heard this and came to join in.

From here on it becomes one story. The usually disciplined soldiers became a mob bent on trashing, looting and burning. Their first objective was, naturally, the two cinemas, the Pall Mall and the Colosseum. The screens were ripped down and the premises set alight. Then the mob split up and nothing was going to stop them. Not only were Egyptians' premises put to the torch, but the troops went for anything, including blocks of shops, motor cars, bungalows a book stalls. Twice they returned to the Pall Mall Cinema to make sure that it was burning. They also set alight one of their own messes, and broke down and looted the NAAFI store - mainly a liquor store - and a great time was had by all.

The Helwan Fire Brigade saw the glow of the fires and arrived quickly at the scene, but its task became impossible when the mob cut its fire hoses just as the flames were beginning to be quelled. The Helwan Fire Master appealed to the New Zealand Fire Brigade at Maadi to help them. The Kiwis soon responded, but fared no better than their Helwan colleagues. Their hoses were also cut, and the Kiwis apparently thought this a great joke. Next, the Royal Air Force and Tura Fire Brigades also came to the assistance of the South Africans, but they too could not make much progress. The first fires had started at about 20h30 and were eventually brought under control by 23h15.

But here the show ended.

'When is my number up?' South African troops enjoy a

morning tea and a chat in the Suikerbossie Tea Garden, a

veritable oasis in the wilderness of Helwan opened by Brig

E P Hartshorn DSO DCM VD. (Photo: SANMMH E 0549)

'Die Maskerspelers', Lydia Lindeque's party arrive in

Cairo to play to the South African troops awaiting

repatriation. (Photo:SANMMH, E 0543)

Mr Harry Lawrence addresses the troops at Helwan

awaiting repatriation

(Photo: By courtesy SANMMH. Ref No E 0588)

Consequences of the riots

The General Officer Commanding the 6th South African Armoured Division, as well as the DGO-A, flew in from Italy to address the troops, promising that steps were being taken immediately to speed up the rate of repatriation. Also, a leading member of parliament was flown up from South Africa to assure the men that they had not been forgotten. He, too, promised that immediate steps were being taken to speed up the repatriation process. The troops did not believe him, and he certainly did not receive a warm welcome.

To tighten up on discipline and improve morale at Helwan, the housing of troops on a unit basis - keeping the men of the same unit together - was put into effect immediately and a brigadier was appointed to command the depot. A public address system was installed to keep everybody in camp up to date on the latest news, thereby reducing the likelihood of rumours. Outdoor cinema shows would be free and a tea garden was established at the swimming bath. Letters of complaint by soldiers were not to be published in the press.

Thus ended the Helwan episode.

On 26 August the Director General Officer - Administration (DGQ-A Italy & Egypt) appointed a court of enquiry by means of Special Order No 111 to investigate the whole matter of the 'disturbances', as he called them, that occurred at Helwan on the night of 20 August. The court would be headed by a colonel as President, with two lieutenant-colonels, and an officer of field rank from the 6th Armoured Division, as members. Te terms of reference were very wide, but basically amounted to:

- What were the causes of the disturbances?

- Were any complaints ever made? If so, were these ever investigated, and with what

result?

- Were there any leaders and, if so, who were they?

- What damage was caused, particularly by fires, and were the camp's fire precautions

adequate?

- The Court was also to make recommendations on the establishment of good order and military

discipline on the camp in the future.

The very first paragraph of the court's findings speaks of the frustration and despondency felt by the troops, and of the overcrowding caused by what they had been led to believe would be the rate of repatriation by air. The first official statements - supplied to The Springbok newspaper by the Staff of the DGO-A on 24 and 31 May declared that the repatriation rate by air would be 500 a day. Later, from 1 July, this figure was amended to 300 a day, but even this was never achieved. The average daily number of men repatriated during the first twenty days of July was only 108.

In the next paragraph, the court draws attention to the announcement by the higher authorities that 2 500 men a month would be repatriated by sea, a figure optimistically raised on 9 August to between 3 000 and 4 000 in that month. However, on 15 August, they had to inform all concerned, with the inevitably depressing results, that the expected shipping had been delayed.

In sub-para (iii) the court reports on the messing conditions in the camp which had contributed to the low morale of the men. Kitchen staffs were inadequate from the beginning and demands for additional trained staff ware made from an early stage, constantly repeated, but with no result. It appears that the shortage of master cooks occurred in both Italy and Egypt.

In sub-para (iv), the court describes the report published in The Springbok on 26 July, in which the DGQ-A asks for 500 volunteers to return to South Africa immediately to assist with demobilisation, thus creating the impression that a lot of people 'back home' were not interested in the welfare of the returning troops.

From the above, it is obvious that the DGQ-A should have been fully aware of the situation

at Helwan, which led to the circulation of rumours. Add to this the condition and dispirited

state of mind of the men coming from Foggia, which soon spread around the camp, and a large

number of minor complaints which were also listed:

- admission fees being charged at cinemas;

- the sale of tickets at cinemas in excess of capacity;

- high charges being set by Egyptin traders in camp;

- objections to the Egyptians as food handlers;

- dirty mess halls;

- the 'suppression' of The Springbok newspaper of 2 August - allegedly for publishing

true pictures of events within the camp - and numerous others.

In its findings, the court was unable to identify any person or group as the leader(s) of the disturbances. It was pointed out, however, that some witnesses had not been completely truthful in giving evidence.

The court assessed the total cost of the damages, mainly from fires at £22 768 431. It found that the fire precautions were adequate; that the Helwan Fire Brigade was soon on the job, but that their efforts had been frustrated because the rioters cut the fire hoses. The local fire master had sent an urgent appeal to the fire brigades for assistance, as a result of which two tenders came from each of the RAF, the New Zealand, and the Tura fire brigades. However, they too had fire hoses cut. Reports from some of those present say that the New Zealanders seemed to treat the matter as a joke and appeared to side with the rioters!

End of box.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org