The South African

The South African

The Welsh Hospital was one of a number of private initiatives in the medical services that were accepted and used by the British Government during the Anglo Boer War (1899-1902). It was organised by Professor Alfred W Hughes, assisted by a committee elected from the men and women of Wales. Funds amounting to £12 000 were acquired by subscription from the citizens of Wales and Welshmen residing outside the country. According to a Report by the Central British Red Cross Committee on the Voluntary Organisations in the Aid of the Sick and Wounded during the South African War, the personnel originally comprised three senior surgeons, two assistant surgeons, eight medical students and dressers, ten nursing sisters, two maids, 48 orderlies, cooks, and stretcher bearers. The medal roll lists 44 staff (W A Morgan, 1975, p 12). With them was the matron, Marion Lloyd. One of the senior surgeons was Professor Thomas Jones, who was a professor of surgery at Owen's College, Manchester, England (Report by the CBRCC, 1902; British Medical Journal, p 250).

The personnel and equipment under the command of Major T W Cockerill embarked from Southampton on the Canada, 14 April 1900. The passage and freight was provided by the government. The stores, subsequently sent out, were shipped at the expense of the organisers. The stores weighed nearly 41 tonnes, and were augmented by a large number of tents bought in Cape Town (British Medical Journal, p 252).

The hospital arrived in Cape Town on 3 May 1900. From this date until 20 May, the personnel were occupied with the removal of the hospital to Springfontein, an important railway junction in the southern Free State. At this time, Bloemfontein was in the grip of a great typhoid epidemic, which was decimating the British troops stationed there. The surgeons and dressers received orders to assist in the military hospitals in Bloemfontein. The hospital staff were not immune. One of the dressers, T R Eames, contracted dysentery and died on 27 May 1900. 'We were considerably depressed by the death of Mr Eames, and we were glad to leave Bloemfontein for the Welsh Hospital at Springfontein, where we were installed on May 31st.' (British Medical Journal, p 253).

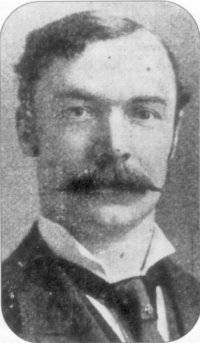

Professor Alfred W Hughes (1861-1900).

Buried in Corns, Wales, United Kingdom.

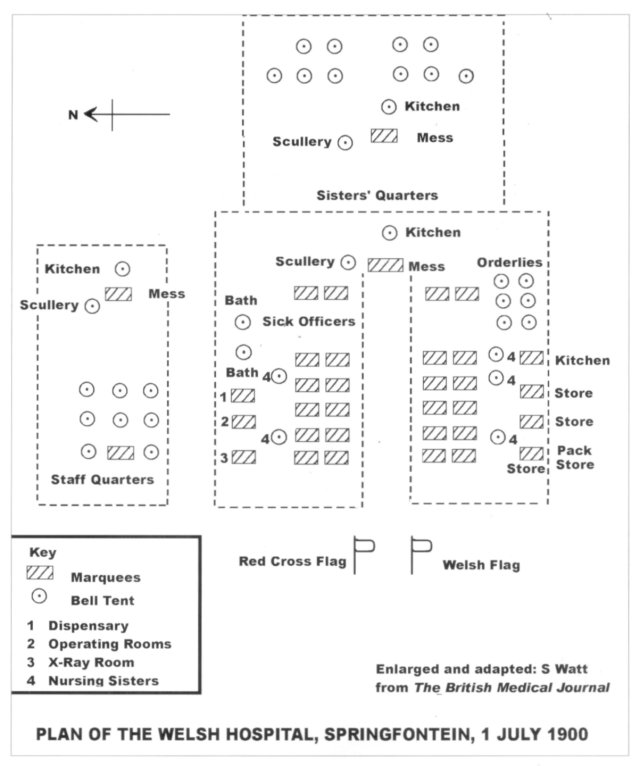

The hospital was situated on sloping ground 1 520 metres above sea level, about half a mile (800 metres) east of Springfontein Station. The frontage was due west, with an extensive view of undulating veld and the distant kopjes. Our left flank is protected by a series of low kopjes, on which are mounted some 4,7-inch guns, and to our rear are several other kopjes surrounded by carefully laid mines (British Medical journal, p253 The writer could not find any corroborating statements to support the assertion that artillery pieces and mines were at Springfontein.)

PLAN OF THE WELSH HOSPITAL, SPRINGFONTEIN, 1 JULY 1900

The hospital, like many others, was housed in tents on the veld, and began to receive patients on 7 June. The array of white tents comprised twenty marquees, four for officers, containing four heds each, and sixteen for other ranks, containing seven beds each (South African Honours and Awards, 1987, p36).

The staff looked forward to a happy time at Springfontein. However, misfortune dogged their footsteps. One of the nursing sisters, Miss Florence Sage, who nursed Mr Eames in Bloemfontein, became ill with dysentery. A few days later, Dr Herbert Davies contracted the same disease. He had served with the No 8 General Hospital in Bloemfontein with Mr Eames. Miss Sage died on 12 June and Dr Davies on 15 June 1900.

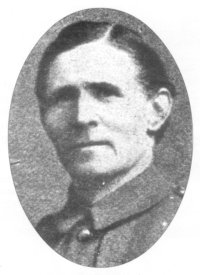

Doctor Herbert Davies (c1874-1900).

Buried at Springfontein.

THIS PHOTOGRAPH IS OF PROF THOMAS JONES - SEE ADDENDUM

A contemporary photograph of Prof Jones.

These misfortunes cast a heavy gloom over the camp. The staff were depressed, but things turned for the worse when their chief, Professor Thomas Jones, died on 18 June 1900 (British Medical Journal, p 253). The circumstances surrounding the death of Jones are sad and tragic. Professor Jones was upset by the deaths of the staff. Dr Davies was an old house surgeon of his and Mr Eames an old dresser (British Medical Journal, p 253). Jones was described as 'one of the kindest and most conscientious of men. But his nature was far too sensitive and tender for a rough campaign... He suffered from insomnia, he lost his appetite, his pulse became irregular and intermittent. We were anxious to get him away, but feared that he was not strong enough to travel' (M Jones).

For some days there had been rumours of a possible attack on Springfontein. On the evening of 18 June 1900, some shots were fired on the koppies behind the hospital. These were followed by volley firing and the command 'lights out'. It was thought that there was a night attack and preparations were made accordingly. It was later discovered that the firing was due to a false alarm.

Professor Thomas Jones (c 1848-1900).

Buried at Springfontein.

THIS PHOTOGRAPH IS PROBABLY HERBERT DAVIES

SEE ADDENDUM

On hearing of Professor Jones's death, Professor Hughes rushed out to South Africa to take charge of the hospital, arriving in Springfontein on 4 July 1900. In addition to his normal duties, Hughes began to give lectures in anatomy, which were 'so good that the Welsh Hospital became the envy of all, and permission was asked by the staffs of other hospitals to attend' (British Medical Journal, p 945).

The month of July 1900 was a busy one. The hospital had been increased from 100 to 150 beds. There was a great number of patients with enteric (today called typhoid) fever. There were some interesting surgical cases too. Reports make mention that 'any part of the body could be perforated by a Mauser bullet with impunity. Very few cases were followed by serious results - the vast majority of cases healed quickly' (British Medical Journal, p 945).

Medical problems were not confined to patients only. The staff had their discomforts too. 'The dry, cold nights and the hot, dry days brought on soreness of the hands amongst our staff... the indolent sores were raw, red which neither showed any signs of inflammation nor any inclination to heal. A week in the humid atmosphere by the sea cured the sores in two of our sisters' (British Medical Journal, p 1276).

On 30 July, orders were received for the Welsh Hospital to proceed to Bloemfontein and then to Pretoria. Having transferred the sick and wounded to the No 3 General Hospital, the staff took their belongings...tents, stores and equipment...to the railway station the following day. Due to a scarcity of locomotives, departure was not until the next morning. The nursing sisters had already departed, but the remainder of the personnel were detained for three days and four nights on the train. The weather was cold and wet for the remainder of the journey (British Medical Journal, p 1276; Report CBRGC, 1902).

In Pretoria, a site was selected on Howitzer Hill, situated between the No 1 General and the Langman Hospitals, about 2.5 miles (4km) east of Pretoria overlooking the town (British Medical Journal, p 1276). With an increasing number of patients being admitted, the number of beds was increased from 150 to 200. On 30 September 1900, the hospital was handed over to the army when it became the officers hospital. At the same time, it was credited by the officials present for being the model and the smartest military hospital in South Africa. On this day, an English doctor-turned-newspaper correspondent, Dr James Alexander Kay, wrote the following: 'It is a small town in canvas. Streets and avenues are marked out with whitewashed stones, the lines and angles geometrically accurate. The tent pegs were also in line and running parallel to the street. The grounds were tidy and clean'(M Jones..).

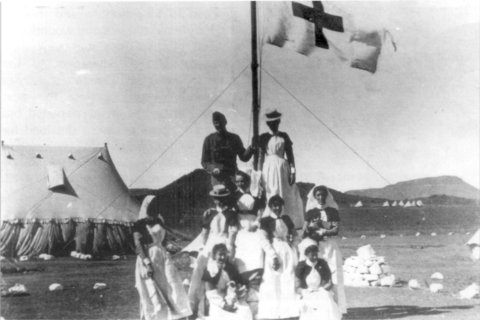

The site of the Welsh Hospital then -

nursing sisters pose for a photograph next to

the Red Cross flag.

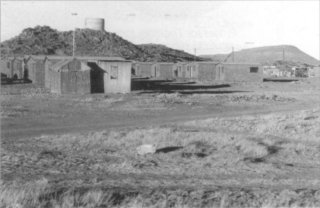

The site today - looking north-east in the

settlement of Maphodi on the eastern outskirts

of Springfontein.

The hospital continued its work until 15 November 1900 Report CBRCC, 1902, p 49). During its service in South Africa, the total number of cases treated was 1107, of whom ten died (M Jones).

Professor Hughes and most of the staff returner to Wales in October 1900. Again, the spectre of disease followed them. Hughes died of enteric fever at home in London on 1 November 1900. A fine memorial to him was erected by his friends in his home town of Corris, Merionethshire, Wales. The Cardiff Medical SchooI initiated a gold medal for the best student in anatomy in his memory. (SA Honours and Awards, p 58).

Marion Lloyd remained in Pretoria as matron of the Officer's hospital and thoroughly enjoyed life there. She frequently rode horses and established around her a sociable circle of officers and local personalities. She worked hard, was mentioned in dispatches by Lord Roberts, and was awarded the Royal Red Cross for her services. This was Gazetted for the Welsh Hospital (M Jones; SA Honours and Awards, p 36). Sadly, tragedy was to strike again. She contracted a fatal disease and died on 17 Decemher 1901 (M Jones).

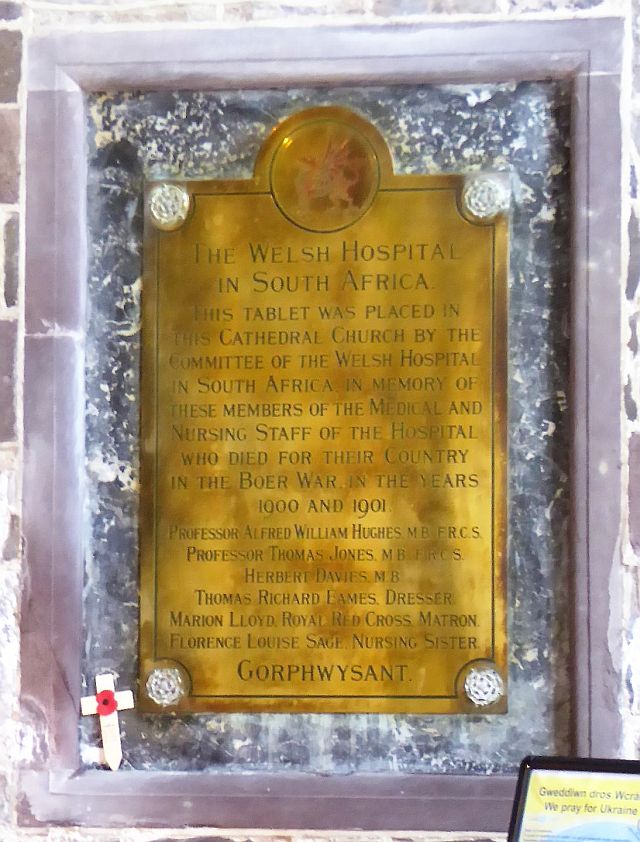

On their return to Wales, the committee of the Welsh Hospital erected a memorial to those who had died. In St David's Cathedral, Pembrokeshire, is a brass plaque which lists the six who died, with the epitaph in Welsh 'GORPHWYSANT' (Rest in Peace)(M Jones). The plaque was unveiled in August 1904 by Lord Penrhynb, the biggest contributor to the hospital subscription fund. Above it hung the flag that had proudly flown in South Africa (S Watt, 2000).

The site today

The Welsh Hospital stood in what is today the settlement of Maphodi in the eastern municipal area of Springfontein. The scene of extensive building activity in recent years, views of the hospital site as seen in old photographs are a virtual impossibility today.

The military cemtery, 1,5 km to the south contains the graves of 299 Imperial servicemen. There are also 663 Boer burials, according to the number of names on panels at the entrance, all of whom perished in the concentration camp at Springfontein. Access to the cemetery is from the eastern side of the railway station. Signs direct the visitor to the site along a road which is the old trackbed between Springfontein and Bethulie.

Among the military graves are three impressive memorials:

Sacred to the memory

of

Florence Louise Sage, A N R

Nursing Sister on the Staff of the Welsh Hospital

Serving the British Forces during the South

African War.

Born Novr 27th 1867. Died at Springfontein

June 12th 1900.

Erected by Welsh Hospital Committee.

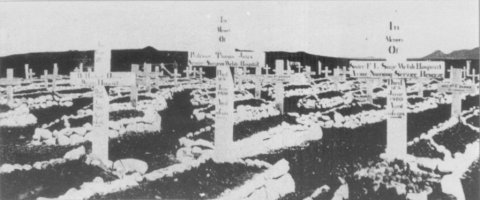

Then - the military cemetery in Springfontein, showing

the graves of Dr Herbert Davies, Professor Thomas Jones, and

Nursing Sister Florence Louise Sage.

The Springfontein Military Cemetery - the same view in 1998

Located in the old cemetery in Pretoria in Grave No 1054:

For those medical personnel who died in South Africa one is not remembered. T R Eames, who died on 27 May 1900, is buried in the large cemetery in Bloemfontein, but his name does not appear on any memorial.

British Medical Journal, July 1900, October 1900, December 1900.

Black and White, Vol 18, c 1900.

Graphic, 1900 and 1901 issues.

Jones, Meurig, 'The Welsh Hospital at War,

South Africa' in Soldiers of the Queen, No 64.

Morgan, WA Capt, 'The Welsh Hospital in South Africa, 1900-1901'

in Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society, Vol 14, No 146, 1975.

Report by the Central British Red Cross Committee on Voluntary Organisations in Aid

of the Sick and Wounded during the South African War (London, 1902).

South African Honours and Awards (reprint, London, 1987).

Watt, Steve, In Memoriam. Roll of Honour

Imperial Forces, Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902

(Pietermaritzburg, 2000).

Acknowledgements

The writer is indebted to Ms Alison Cadick of the Medical Library, University of Cape Town, for the information in the British Medical Journals and for the Report by the British Red Cross; to Macrorie House Museum, Pietermaritzburg, for the photographic album of Edith Mary Chamberlain; and to the Natal Society Library, Pietermaritzburg, for access to the Graphic magazines.

Addendum to this article added in July 2022

following e-mailed information from David Redhead

St David's Cathedral Welsh Hospital in South Africa Memorial

Above photo is of the St David's Cathedral Welsh Hospital in South Africa Memorial. As with any brass plaque memorial, light reflections made getting a decent photo difficult. The task was made more difficult by candles burning nearby in support of the people of Ukraine. The answer was to stand well back and use the zoom lens and hence the fragment of the notice regarding the candles in the bottom right hand corner.

Having done some more research on the Welsh Hospital I have noticed two definite errors in Steve Watt's excellent article.

The memorial in St David's Cathedral was unveiled in August 1902 and not 1904 as Steve reports. I can provide numerous contemporary newspaper articles to prove the point. One includes a sketch which shows Steve was correct about a flag once flying above it. The on-line Pembrokeshire War Memorial Project also states it was unveiled in 1902.

More importantly the photo of Herbert Davies is incorrect, it is of Professor Thomas Jones. I presume the one he says is Professor Thomas Jones is actually Herbert Davies and he got them mixed up when assembling his article but I obviously don't know that for certain. Attached is a photo that appeared in the Lancet which proves the point - I don't think we can argue with the Lancet (this I found attached to his profile on an Ancestry Public Family Tree). Also at least two contemporary papers carry the picture Steve used for Herbert Davies to report the death of Professor Jones and I have attached one that I have extracted.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's

Home page