The South African

The South African

The South African Aviation Corps (SAAC)

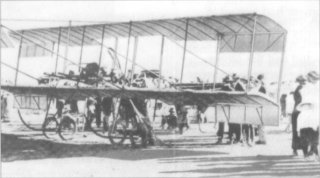

Although the official date of the establishment of the South African Aviation Corps was 29 January 1915, as proclaimed by the Department of Defence in Pretoria, the roots of this service go back to December 1913. In that month, Compton Paterson, British aircraft designer, flying instructor and owner of the Paterson Aviation Syndicate School in Kimberley, certified that seven of his Government candidates had flown the Paterson biplane unaided, and were thus able to qualify for the FAI Certificate.

When training had begun in August, there were two training aircraft for ten candidates, but when one of the planes was wrecked in a crash, during which the pilot died, they were left with only one. This severely handicapped the training programme. Training took place on the first South African aerodrome at Alexanderfontein, Kimberley, and the trainees jokingly referred to themselves as 'the stick and string flyers club'. The pupils were taught to fly turns to the right and left, and to raise or lower the machine to heights as directed. They were also instructed in aircraft repairs and engine overhauls.

The Paterson biplane was a pusher aircraft with a 50 hp Gnome engine, at that time the most favoured type of engine for aircraft manufactured in Britain and on the Continent. The plane itself was similar in design to the Farman, although not of the same quality and airworthiness.

Compton Paterson's Farman biplane

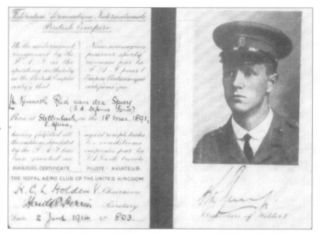

Six of the original group of pilots were chosen to undergo further training in Britain, and were appointed as probationary lieutenants of the South African Defence Force. They were: Kenneth van der Spuy, Gordon Creed, Marthinus Williams, Basil Turner, Gerard Wallace and Edwin Emmet. All took part in preliminary courses at Tempe, Bloemfontein, before being sent for training at Upavon. When van der Spuy passed his final examination on 2 June 1914, and was granted the certificate of the Royal Aero Club, he was South Africa's first qualified military pilot. The others passed a few days later.

The FAI licence issued to South Africa's first qualified military pilot, Lt Kenneth Reid van der Spuy on 2 June 1914

In January 1914, Defence Headquarters purchased the Paterson Aviation Syndicate School, the aircraft and all spares, but the biplane was never put to any use and was found years afterwards in a Cape Town Drill Hall in a dilapidated condition. Its later fate is unknown. Early in 1915, van der Spuy, Creed, Turner and Wallace were asked to establish a South African Aviation Corps (SAAC) in England and make preparations to go to South-West Africa to assist the South African land forces under General Louis Botha in their fight against the German Schutztruppe.

Compton Patterson and Emmet with the second aircraft

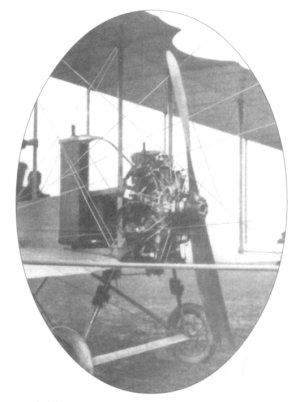

It was a monumental undertaking for the young officers and they had to persuade, beg and collect not only the aircraft required for such a venture, but spares, equipment and supplies of any kind as well. For this they had to deal with the War Office, the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Navy, all august bodies with their own rules of doing business, and not in the least inclined to assist. Eventually they managed to prise six all-steel Farmans from the Flying Corps, with the suitable 150 hp French Canton-Unne engines generously supplied by the Admiralty. In addition two BE 2C aeroplanes were shipped off, and three flying officers - Lieutenants Cripps, Wood and Henshilwood, seconded from the Royal Flying Corps. However, the BE 2Cs were underpowered, their wooden frames warped during the sea voyage and dried out in the African heat, and they were therefore useless. By the end of May 1915, all aircraft and equipment had arrived in Walvis Bay. As a consequence of a wet voyage, when the Farmans had been lashed in crates on deck, two aircraft had to be reconstructed and the others thoroughly cleaned. When the first plane was ready, van der Spuy made the first reconnaissance flight on 6 May 1915 over the area around Walvis Bay.

Afterwards, General Louis Botha declared, highly pleased: 'Now I can see hundreds of miles', and he even recklessly joined van der Spuy on a demonstration flight, after having been assured by the pilot that it was safe to do so. That the trip did not end in disaster for the General was due to the pilot's quick thinking. After the plane took off, the engine faltered and lost revolutions, as often happened in early aircraft, and he just managed to turn the plane in a wide circle to land back at the airfield.

From Walvis Bay, the aircraft were flown to Karibib where they could make use of the existing German airstrip and hangars. This place became the first base of the SAAC, although they operated later from other airfields as well. By this time the German aircraft had ceased operations and no aerial battles took place. The tables were turner and the SAAC had a clear run during their reconnaissance missions. Occasionally they dropped 20 and 120 pound shells on the enemy, and a lucky hit destroyed a locomotive at Tsumeb. One report mentions that van der Spuy crashed his plane when he ran out of fuel and broke a leg, but otherwise there were no casualties or serious engagements, and the whole exercise was a bit of an anti-climax.

After having flown over South-West for just about two months, the unit was sent back to England to become No 26 (South African) Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Their emblem was a Springbok with crown and wreath and the motto: 'n Wagter in die Lug. They went into training in September 1915 and left for East Africa on Christmas Day 1915, to arrive four weeks later in Mombasa after a stormy, arduous voyage. They were put into action almost immediately. They flew their BE 2Cs on photo-reconnaissance and occasional bombing missions against the Germans, although not in the rainy season.

A Henri-Farman in Africa, showing the Canton-Umme 150 hp engine

Until the arrival of No 26 Squadron, a small flight of the Royal Naval Air Service had assisted the land forces in the East African Campaign. They flew Voisin-Farman Ill aircraft and two Caudron GIII biplanes which had come out in 1915, and operated from a specially constructed airstrip on Mafia Island, south of Dar-es-Salaam. However, only one aircraft of each type was able to assist the gunboats against the German cruiser Königsberg in the Rufiji Delta, but their effectiveness was somewhat reduced by the anti-aircraft fire from the German ship and the planes' consistent engine failures.

Two versions exist of how the Königsberg's original location in the Rufiji Delta was discovered. According to one source, it was H D Curtiss from Cape Town who owned two Curtiss pusher seaplanes which he offered to the British forces in East Africa early on in the Campaign. These were shipped from Cape Town but arrived damaged, and it took some time before at least one was operational. The machines were built mainly from wood, and had fabric covered wings. The hull was made from plywood. The restored aircraft crashed on its first flight, discovered the German warship on its second, and was totally destroyed when it crashed on its third flight. According to the second, and much more acceptable version of the story, credit for the discovery of the Königsberg goes to Major Pieter Pretorius, a South African who had farmed and hunted extensively in the delta area. He undertook a scouting mission and fixed the exact position of the cruiser.

When the last battle for the Königsberg began on 6 July 1916, the Farman served as spotter for the gunboats until it was hit and forced to crash land in the water. Both pilot and observer were rescued. The Caudron took over but was not needed any more, as by then the German cruiser had been so badly damaged that it settled deep in the mud and was abandoned by what remained of her crew.

By May 1916, more Farmans had joined the squadron. It has been claimed that these were the same planes that had operated in South-West, but considering the wear and tear they must have suffered, and the additional hazards of a sea voyage round the Cape, this seems rather doubtful.

A Be 2a aircraft in German South-West Africa (Photo: By courtesy SA National Museum of Military History)

As the Campaign developed, the unit was almost constantly on the move. They flew photo-reconnaissance sorties; they bombed troop concentrations or targets such as railways and bridges; and they maintained communication between the forces in the thick bush and mountains. It was an exhausting campaign. Fever took a heavy toll. There were losses of pilots and aircraft through forced landings and crashes, and spares, petrol and bombs were forever harder to obtain.

At the end of 1916, No 26 Squadron, or what was left of it, returned to England to be disbanded. By then it had become apparent that the war had developed into a series of hit-and-run skirmishes by the steadily dwindling German forces, and planes were too expensive and unsuitable to take any further part.

Nevertheless, these flimsy, vulnerable, grand early aircraft, whether flying on the German or Allied sides, proved their worth beyond all doubts and under almost any conditions. They, and their courageous pilots, who risked life and limb, will never lose that special nostalgic magnificence.

Bibliography

D Botting, The Giant Airships (Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, 1981)

Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt, Die

Militäluftfahrt bis zum Beginn des Weltkrieges

1914 (Verlag Mittler & Sohn, Frankfurt/Main, 1965)

J Heuchling, 'Deutsch-Ostafrika im Ersten Weltkrieg',

Deutsches Soldatenjahrbuch, No 42/3 (Schild-Verlang, München)

Kolonie und Heimat, No 36, 1914 (publisher unknown)

G L'ange, Urgent Imperial Service (Ashanti Publishing, Pretoria, 1991)

P Meyer, Luftschiffe (Verlag Wehr & Wissen, Koblenz, 1980)

S Monick, 'The Drama of the Konigsberg' in Museum

Review, September 1987, SANMMH, Johannesburg

Militaria, 2/1, 1970, Defence Headquarters, Pretoria

H Oberholzer, 'Pioneers of early aviation in South Africa', Memoirs van die

Nasionale Museum Bloemfontein, 1981.

G Plueschow, Die Abenteuer des Fliegers von

Tsingtau (Verlag Ullstein, Berlin, 1916)

W Reith, 'Das gegebene Land für die Flugmaschine' in

Afrikanischer Heimatkalender 1998 & 1999, Windhoek.

K van der Spuy, Chasing the wind (Books of Africa, 1966)

P Supf, Deutsche Fluggeschichte, Vols 1 & 2 (Verlag Hermann Klemm, Berlin, 1935)

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Orbis Publishing Ltd, 1986)

The Times History of the War, 1914-1918, Vol VIII

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org