The South African

The South African

Lord Roberts and the Boer War Victoria Crosses

The Victoria Cross is perhaps the most discriminating gallantry award in the world, universally recognised as one of the highest standards of valour. It was created during the last days of the Crimean War as royal recognition of acts which caused Queen Victoria to 'tremble with emotion, as well as with pride, in reading the recital of the heroism of these devoted men' (Monica Chariot, 1991: p 352, quoting Queen Victoria's journal entry, 12 November 1854). During the decade that followed its institution, a number of parameters concerning the calibre of Victoria Cross heroism were established, and by 1870 a firm institutional understanding of what could and could not be recommended existed.

The Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 created two even more lasting changes in the nature of the Victoria Cross: the institutional (but not statutory) elimination of provisional bestowal of the cross by the theatre commander, and the extension of the cross as a posthumous decoration. Both of these developments were connected either directly or indirectly to Victorian Britain's most loved soldier, Lord Roberts of Kandahar.

Sir Redvers Buller had been the initial theatre commander for South Africa, but after a series of embarrassing defeats, he was replaced by Lord Roberts late in 1899. While Roberts exhibited a better grasp of field operations against the Boers than had Sir Redvers, he made some astonishingly bad decisions concerning the Victoria Cross.

The Korn Spruit affair

On the evening of 30 March 1900, a British column of some 1 800 men under the command of Brigadier General Robert George Broadwood bivouacked at Sanna's Post, which guarded the waterworks supplying Bloemfontein. As the force sent out no patrols, they were unaware that Christian de Wet and a force of 1 600 commandos with artillery support were in the immediate area. De Wet had not made the same mistake, and was well aware of the British presence. He resolved to drive them into an ambush when they proceeded towards Bloemfontein in the morning. The spot he chose for the trap was the drift crossing a rivulet called the Korn Spruit (Byron Farwell, 1976: p 257).

Despite a report by an early morning patrol that they had been fired on, Broadwood ignored the possibility of a large Boer presence until the first enemy artillery round from across the Modder River landed in his midst at around 06.30. As the men were getting their breakfast, considerable chaos ensued. The logical course of action for the British was to move out of the enemy field of fire towards the safety of Bloemfontein. As shells burst about them, drivers cursed their mules and horses into harness and began to move out, directly into the ambush at the drift (Louis Creswicke, l900: pp 3-4).

First in line were the vulnerable supply wagons. De Wet's Boers captured them without a shot being fired. Scrub bush and the slope of the drift concealed their capture from the rest of the force. Broadwood still had no idea of the proximity of the Boers when he ordered U and Q batteries of the Royal Horse Artillery to follow the supply train and take up positions on the other side of the drift to cover the general retirement of the force.

U Battery, in the lead, stumbled into the ambush as neatly as had the supply train, but in the confusion of their capture Major Philip Taylor managed to slip away and wave off Q Battery. Their sudden wheel about to escape the drift prompted De Wet's riflemen to open fire. Pandemonium reigned in Korn Spruit as the now driverless teams of U battery bolted, some becoming hopelessly entangled, others madly galloping across the plains toward Bloemfontein (B Farwell, 1976: p 259).

The situation was scarcely better for Q Battery - one gun and two ammunition wagons overturned in the violent manouevre and had to be left behind. The survivors retired to the three buildings at Sanna's Post, roughly 1 000 yards (914 metres) from the Korn Spruit, unlimbered, and opened a lively, if entirely ineffectual fire on the Boer positions. The drift offered excellent cover from the flat trajectory of the field guns at that range. The guns, without any splinter shields, offered no shelter from the fire of 350 Mausers (B Farwell, 1976: p 259).

The gunners of Q Battery were caught in the open fire by a foe who knew their exact range. Casualties steadily mounted until the order arrived to fall back behind the cover of the buildings. The fire was so heavy that Major Edmund Phipps-Hornby ordered the guns run back by hand rather than expose the horses. Assisted by troopers from the Burma Mounted Infantry - their own numbers too depleted by this point - Q Battery managed to withdraw four of the five guns to safety. The fifth was abandoned (L Creswicke, 1900: pp 6,8). The day had been an unmitigated disaster - 570 casualties; seven guns captured by De Wet's commandos (H Smith-Dorrien,1925: p 179).

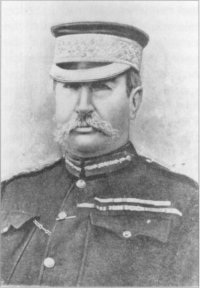

LORD ROBERTS OF KANDAHAR

(PHOTO: BY COURTESY, SANMMH)

Amazingly, Lord Roberts conferred a provisional Victoria Cross on Major Phipps-Hornby, and directed the battery to elect three members to receive the same decoration as their commanding officer. These three, Gunner Isaac Lodge, Driver Horace Henry Glasock, and Sergeant Charles Edward Haydon, were likewise given provisional VCs in the field. Roberts also forwarded three more candidates for crosses through the regular channels. The whole packet was presented as a fait accompli to the War Office (PRO File WO/32/ 7878: Memorandum from the War Office to Her Majesty, 12 June 1900).

That four provisional VCs were awarded on a single engagement raised some eyebrows in London. That it was for a debacle such as Korn Spruit was remarkable. That Lord Roberts further recommended three additional candidates was unbelievable. His actions resulted in near censure from the War Office.

London realised that it could do nothing about the four VCs already granted. To deny them would undercut Roberts's authority as theatre commander. They could and did quash the three further recommendations. The original draft of the letter (PRO File WO/32/ 7878, 079/2536, c June 1900), informing him of this was quite curt, a rebuke to Roberts: 'The grant of four Victoria Crosses for an affair which, taken as a whole, was highly discreditable, is ample recognition of the service rendered; to give seven would be very inexpedient.' The final draft softened the phrasing somewhat to read: '...taken as a whole was not of a nature to reflect credit on our army...', but the message remained clear. Roberts had made a grievous error. Equally clear was the message that provisional conferral of the VC was a thing of the past.

Originally, the bestowal of crosses by the commander on the spot reflected the nature of communications available at the time. The far-flung posts of the Empire were often weeks, if not months, from contact with the authorities in London. It was therefore thought proper to award the medal in a timely fashion for two reasons. Firstly, praise deferred might seem begrudging a hero of his laurels, and thus the award should be given while the deed was still fresh in the mind's of his comrades.

Secondly, a seriously wounded candidate could - and on occasion did - die before the recommendation could he confirmed and the medal awarded (PRO File WO/98/2. Letter, Col H Warre to Lt Gen John L Pennefather, 9 April 1857). In the initial years of the cross, it was widely assumed that bestowal in the field would become the rule rather than the exception (The Times of London, 26 June l857:p 7).

The Korn Spruit incident, however, put an end to provisional bestowal. While the warrant retained the clause permitting it, no other commander had the temerity to chance granting a cross in the field after Roberts's experience. When the warrant was redrawn in the wake of the First World War, the provisional bestowal clause was quietly omitted, and thereafter only recommendations coming through proper channels were eligihle for the award (Clause 8, warrant of 1920)

Korn Spruit also created a further controversy. Late in 1901, Colonel Edward Owen Hay, Assistant Adjutant General for the Royal Horse Artillery, made an astounding request. He argued that as the VCs granted to Q Battery for its action at Sanna's Post had been elected by the battery, it was in effect an award to the battery bestowed on individuals. Therefore, the battery itself, an immortal corporate entity, had won the VC collectively and should be allowed to let all of its current and future memhers wear some form of permanent badge on their uniform to represent this accomplishment. Whether intentional or not, it is interesting that Hay never referred to the action as Korn Spruit, but only as Sanna's Post (PRO File WO/ 32/7474. Memo from Col E 0 Hay to Adjutant General's Office, 9 December 1901. Memo from Adjutant General to General C-in-C, 29 January 1902).

After reviewing all the cases in which a unit had elected winners under Clause 13, dating all the way hack to the Indian Mutiny, the Adjutant General's Office determined that there was no precedent for a unit citation interpretation of the regulations. On 1 February 1902, the Adjutant General wrote to Colonel Hay (PRO File WO/32/ 7474) that the 'VC, if possible, should be a purely personal distinction. I think it would not be anything but misleading to allow staff segts [sic] to wear VC as a badge.' He added the admonition 'please note, this ends the matter'.

The posthumous VC

Why had Roberts suffered such a severe lapse of judgement concerning the cross as to provoke such intense criticism from the War Office and the Horse Guards? The answer may lie in the sequence of events leading up to the admission of posthumous VCs. Once again, Roberts was at the heart of the matter, even though he was in Britain at the time.

Contrary to Victorian military conventions, Frederick Sleigh Roberts had married in 1859 at the age of 26, while still a lieutenant. Only three of his children, however, survived into adulthood, two daughters and a son. Frederick Sherston Roberts duly followed his father's footsteps into a military career, gaining a commission in the King's Royal Rifle Corps (B Farwell: pp 159-60). The winter of 1899 found him in the field against the Boers. Freddy Roberts was a well-liked young officer who tried hard to live up to his father's reputation. He was with General Sir Redvers Buller's staff on 15 December 1899 at the disastrous battle of Colenso. Colenso has been rightly condemned as one of the most ineptly conducted actions in the annals of British military history, and more generally as a prime example of how not to fight a hattie. Its role in the evolution of the Victoria Cross as an institution is less well known. A split-second decision by a lieutenant precipitated a complete reversal in the interpretation of the Victoria Cross warrant, and led to an incident of favouritism unparalleled since the Havelock incident of the Indian Mutiny, when a commanding officer father bestowed a provisional cross on his own son.

Lack of proper reconnaissance led Buller to believe Colenso was deserted or, at worst, only slightly defended (L Creswicke, 1900, II: p 189). When it became apparent that this assumption was wrong, Buller lost control of the battle and instead became obsessed with trying to save the guns of the 14th and 66th batteries. These guns had become exposed and had to be abandoned due to the rashness of the battery commander, Colonel Chris Long. His own philosophy was 'the only way to smash those beggars is to rush in at 'em.' (B Farwell, 1976: p 127). Appropriate action, perhaps, for a cavalry regiment - recommended, even, when dealing with a 'savage or aboriginal' foe - but hardly sound doctrine when facing an enemy equipped with modern rifles (C Calwell, 1906: pp 429-32). Buller had given only ambiguous orders for the deployment of the artillery, instructing Long to use his best judgement in siting the guns. Long's best judgement was to gallop past the advancing infantry for a full mile (1 609 metres) and unlimber his guns in a completely exposed position, taking care to dress his formation to parade ground perfection before opening fire (W Pemberton, 1964: p 138 and B Farwell, 1976: p 128). The horses and limbers were sent back to a shelter in a donga some 800 yards (731 metres) to the rear.

Long's guns fired more than 1 000 shells within an hour of being unlimbered, and ran short of ammunition. The gunners took twenty-five percent casualties in the process, but managed to silence the Boer artillery across the Tugela. Long himself was hit in the abdomen, and command devolved to Major A C Bauward, who ordered the crews back to the shelter of a small donga about fifty yards to the rear of the artillery park to await more ammunition (W Pemberton, 1964: p139). The guns sat deserted while the Boer cannon, unopposed, returned to action.

Buller and his staff moved forward to oversee the actual entry into Colenso by the infantry which had been supported by Long's fire. En route, they encountered one of the two officers sent to speed the artillery ammunition resupply, and learned that the guns sat unattended in front of the friendly lines. Buller rode immediately for Long's battery to find its commander delirious and raving about his poor brave gunners and the guns themselves exposed and unmanned (B Farwell, 1976: p 133). Possibly suffering from shell shock himself, having less than an hour earlier been bruised by the near-miss of a Boer shell that killed his personal surgeon, Buller lost control and focussed on recovering the guns to the exclusion of all else (W Pemberton, 1964: p141).

SIR REDVERS BULLAR

(PHOTO: BY COURTESY, SANMMH)

Buller first ordered Captain Harry Norton Schofield to take

some teams and drivers out to recover the guns, but they were met

with such a hail of fire that they were forced to turn back short of

the guns. Then, according to Captain Walter Norris Congreve,

who won his own VC that day (L Creswicke, 1900, II: p 200):

'Generals Buller and Clery stood out in it [the dongal and said

"Some of you go out and help Schofield." A D C Roberts, myself

and two or three others went to the waggons, and we got two waggons

horsed up with the help of a corporal and six gunners. I have

never seen even at field firing the bullets fly thicker.'

Freddy Roberts got about 30 yards (27,4 metres) from the donga, laughing and twirling his riding crop, before a Boer shell blew his horse to bits and mortally wounded the young officer (B Farwell, 1976: p 135 and Creswicke, 1900, II: 193, p 200). Congreve and the others were either wounded or driven to cover and the attempt to save the guns failed. A further attempt resulted in two of the guns being dragged to safety, but Buller then lost his resolve. Unwilling even to wait for cover of darkness to retrieve the remaining guns, he ordered a general withdrawal. The remaining ten guns were handed over to the Boers (W Pemberton, 1964: p 142). Buller had given the order that killed the only remaining son of England's most beloved soldier, and had been soundly defeated by the Boers.

LIEUTENANT THE HON F H S ROBERTS, FALLING WOUNDED WHILE SAVING THE GUNS AT COLENSO

(FROM A SKETCH BY F A STEWART,ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS, 20 JANUARY 1900, P75)

Exactly what went through Buller's mind the next day cannot

be stated with any certainty. His own recollections of Colenso and

the aftermath became thoroughly muddled in the process of explaining

what had happened to the War Office. What he did on 16 December

1899 is a matter of official record, however. As Freddy Roberts

lay dying, Buller recommended him for the Victoria Cross,

and in so doing discarded 42 years of precedent regarding badly

wounded heroes.

The VC warrant of 1856 was vague concerning the nuances of eligibility. The fifth clause stated that the award was open to any officer or man who had served in the presence of the enemy and had performed some signal act of valour. The sixth clause specified that neither rank, nor long service, nor wounds were to enter into the determination of fitness for the award and that it should rest solely on the merit of the action. It did not specifically bar the VC to soldiers killed in the process of serving the Queen. That decision originated in the bureaucracy at the War Office.

The precedent for refusing to consider posthumous recommendations

came from Lord Panmure's desk almost before the ink on the original

warrant had dried. Queried as to the possibility of granting a VC

to the father of a soldier who had died in action in the Crimea, he

replied in a letter to Edward Pennington in April 1856 that the

cross 'is an order for the living' (PRO File WO/32/7300). Horse Guards

followed his lead. In a letter to John Godfrey dated 13 May 1856 (PRO

File WO/98/3), Jonathan Peel wrote:

'I am directed by Lord Panmure to acknowledge receipt of your

letter of the 16th ultimo, requesting to be informed whether, as

representing your late son, Lieutenant Godfrey, of the 1st Battalion of

the Rifle Brigade, you would be entitled to prefer a claim under the

Royal Warrant instituting the decoration of the Victoria Cross; and to

acquaint in reply, that this decoration will not be conferred upon the

families of deceased officers, and that it is more in the nature of an

order like that of the Bath rather than of a medal commemorative of

a campaign or expedition. In the case of the Crimean Medal her

Majesty was pleased specially to command that the medals of those

who died should be given to their representatives, but it is by survivors

only that claims to the Victoria Cross will be able to be established.'

From the outset, it was made clear that submitting the names of dead men for the honour would not be tolerated.

In only six cases before the Boer War had this precedent even been

questioned. Private Edward Spence was mortally wounded in an attempt

to retrieve the body of a dead Lieutenant on 15 April 1858. He died

two days later. Ensign Everard Aloysius Lisle Phillipps was cited for

cumulative bravery during the siege of Delhi, 30 May to 18 September

1857, including the capture of the Water Bastion during the assault on

the city. He was killed in street fighting on 18 September. Two

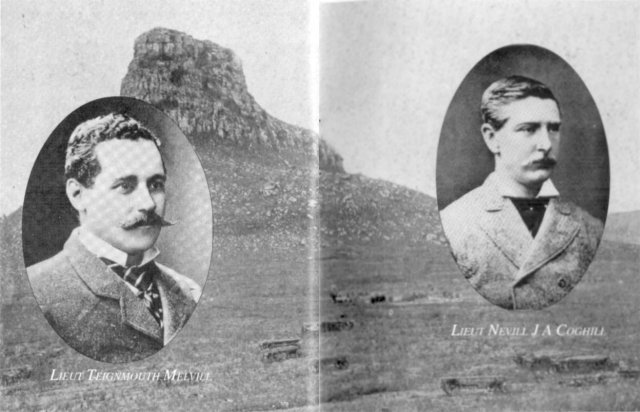

lieutenants of the South Wales Borderers, Teignmouth Melvill and

Nevill J A Coghill, died together at Isandhlwana on 22 January 1879,

trying to spirit away the Queen's Colours from the hands of the Zulu

after the day and the battalion had been lost. More recently,

Trooper Frank William Baxter had lost his life in the Matabele Rebellion

on 22 April 1896, when he gave his horse to a wounded comrade and

tried to escape the pursuing Matabele on foot. At the village of

Nawa Kill, during the Tirab Campaign in 1897, Lieutenant

Hector L S MacLean was mortally wounded in an attempt to recover a

wounded officer. These six were each gazetted as 'would have been

recommended to Her Majesty for the Distinction of the Victoria Cross

had he survived', but no medals were issued (PRO File WO/32/

7498. Memorandum from the War Office to His Majesty, 20 October

1902). In a memorandum from Sir Henry Storks to Captain Colin Yorke

Campbell, Royal Artillery, 6 May 1858 (PRO File WO/98/3), it

emerged that the War Office was careful even of extending

recognition to the dead in this fashion:

'I am directed by Secretary Major General Peel to acknowledge the

receipt of your letter of the nineteenth ultimo regarding that, in

consideration of the deed of gallantry performed by your late

brother Captain Howard Douglas Campbell of the 78th Highlanders

in India, a notice be published in the London Gazette to the effect

that the distinction of the Victoria Cross would have been conferred

upon him had he survived; and I am to acquaint you in reply that as no

distinct recommendation of the late Captain Campbell for this honour

was ever made, his death having taken place a few days after the

performance of the act of gallantry and question, Major General Peel

regrets that he is unable to comply with the request which you have

now made as in the absence of such recommendation it has been found

impossible to bring under Her Majesty's notice the act of heroism

which Her Majesty would no doubt have gladly rewarded had

circumstances permitted.'

In practice, the prohibition against posthumous crosses evolved into a rough rule of thumb applied by commanding officers. Unscathed heroes could be submitted without reservation. Dead heroes could never be submitted. Wounded heroes could be submitted only if there was a strong chance of their surviving their wounds. Buller, whether motivated by shame, guilt, remorse or shell-shock, violated the last principle in his recommendation of young Roberts. He did not deserve a Victoria Cross for his actions at Colenso. All he did was get killed, a distinction he shared with a number of individuals in that donga. At the very most be should have been gazetted as '...would have... had he survived'. Although the general did adhere to the letter of the regulations in recommending the lieutenant before his death, the recommendation was suspect from the moment he set pen to paper.

Bullet was, furthermore, transparent in his padding of the account

of Colenso to justify the recommendation of Roberts. He detailed the

actions of Congreve and Captain Hamilton Lyster Reed in their VC

recommendations (Capt Reed, 7th Battery, Royal Field Artillery, having

heard of the difficulty, had quickly brought down three teams from his

battery to see if he could he of any use. He and five of the thirteen men

who rode out with him were wounded, one was killed, and

thirteen of the 21 horses were killed before he got half-way to the guns

and he was obliged to retire). However, in the case of Roberts,

Buller could only report that 'Lieutenant the Honourable F

Roberts, King's Royal Rifles, assisted Captain Congreve. He was wounded

in three places.' (L Creswicke, 1900,11: p199). He did not mention

that Roberts was acting in response to his direct order to help Schofield,

nor did he state that Roberts's wounds were fatal. In fact, the

report was worded in such away to suggest that he (Buller) was not

present at the time of the event. Also interesting was the slant Buller

attached to his reasons for recommending certain individuals while

skipping others:

'I have differentiated in my recommendations, because I

thought that a recommendation for the Victoria Cross required proof of

initiative, something more, in fact, than mere obedience to orders, and

for this reason I have not recommended Captain Schofield, Royal

Artillery, who was acting under orders, though I desire to record his

conduct as most gallant.' (L Creswicke, 1900,11: p200). Oddly

enough, Buller recommended only those who had failed to retrieve a

gun. He nominated the six drivers who had actually accomplished

their mission and came back with two guns, for the Distinguished

Conduct Medal.

All in all, it is obvious that he was rushing the report, closing it with the statement 'several other gallant drivers tried, but were all killed, and I cannot get their names' (L Creswicke, 1900,11: p200). It truly seems he was trying to dispatch the letter before Freddy Roberts breathed his last.

Buller's recommendation sailed through the adjudication process without comment, and Lieutenant Roberts was gazetted as a Victoria Cross recipient on 2 February l900, along with Congreve, Reed, and Corporal George Edward Nurse. Buller had nominated, and had passed, four VCs for a dismal failure largely of his own making. More VCs were to come of Colenso - Major William Babtie, RAMC, who tended Roberts under fire, was gazetted on 20 April 1900. Captain Schofield received the Distinguished Service Order for his efforts that day as well.

Here the Victorian sense of fair play became part of the process, both inside and outside the administration of the army. It was hardly proper that Congreve and Roberts got the VC for trying to do the same task as Schofield, who received a lesser award. Buller's argument that Schofield was acting under orders, while the others showed initiative, was undercut by Congreve's statement to the contrary. It is unclear who initiated the sequence of events, but once Lord Roberts had handed over command in South Africa to Lord Kitchener and returned to London as the new commander-in-chief, further enquiry was made into the Colenso affair, specifically as to the actions of Schofield. In a letter marked 'secret', Colonel Ian Hamilton, Military Secretary to Roberts at Horse Guards, asked Captain Congreve for his version of events at Colenso (PRO File WO/32/7470: Letter, 7 June 1901).

Based on Congreve's account, Roberts pushed for an upgrade in

Schofield's reward for gallantry and on 30 August 1901 he was gazetted

for the VC. Hamilton wrote the letter informing Buller of this

development (PRO File WO/32/ 7470, letter dated 22 May 1901):

'Dear Sir Redvers

In considering the case ofa soldier of the Royal Scots Fusiliers

recommended for the VC, the question of Captain Sc[h]ofield, and his reward

came up and was discussed by the Secretary of the State and the

Comm[ander] in Chief.

Lord Roberts thinks you would like to know that as a result it is now

intended to give Capt Sc[h]ofield the Victoria Cross instead of the DSO.

This action is taken in assumption that although you did not think

you were justified under the terms of the warrant in recommending

Captain Sc[h]ofield, you would nevertheless be glad to learn he was

going to obtain this great distinction.

With kind regards, sir

yours sincerely, Ian Hamilton'.

(It is interesting to note that Hamilton had twice been recommended for the Victoria Cross himself, and on both occasions his nomination had been denied by Buller as theatre commander.)

The British did not allow stacking awards for the same deed. Thus, when Capt Schofield was awarded the VC, he had to relinquish the DSO already awarded for the same event. In this instance, he had held the DSO for only 30 days before it was reclaimed by the War Office (PRO File WO/32/ 7470, War Office Memorandum, 18 May 1901).

Fair play also dictated a review of cases similar to that of Freddy Roberts. Lord Roberts took the lead in assembling a case for changing the interpretation of the warrant. The long-standing policy of the government concerning the VC was to consider it a hybrid award, combining aspects of both a medal, some of which could be awarded posthumously, and an order, which could not be granted posthumously (PRO File WO/98/2, Letter, Maj Gen J Peel to J Godfrey, 13 May 1856).

Roberts's staff attacked the latter premise, dredging up instances in which an order had in fact been granted to the widow of the man who earned it. The strongest case they came up with was that of Lieutenant Colonel A Fills, 'who would have been recommended for the dignity of Knight Commander of the Bath (Military Division) had be survived' operations on the west coast of Africa in 1894. They pointed out, however, that 'his widow was granted the Style, Plan and Precedence which she would have been entitled to had her husband survived' (PRO File WO/32/7478, Explanatory Memoranda A).

There were six instances in the Boer War involving great courage with fatal results. Horse Guards made a test case out of the actions of Sergeant Alfred Atkinson of the Yorkshire Regiment. On 18 February 1900 he made repeated trips under heavy fire to bring water to the wounded, and was mortally wounded on his seventh traverse of the fire zone. He died three days later. In a memo to the Secretary of State, St John Broderick, on 7 April 1902, Lord Roberts gave his endorsement to granting the VC he should have won to Atkinson's mother, and then recommended that the five other dead heroes be given the same (PRO File WO/32/ 7478). All six - Sergeant Atkinson; Lieutenant Gustavus Coulson, DOW 18 May 1901, Lambrechtfontein; Trooper Herman Albrecht and Lieutenant Robert Digby-Jones, KIA 6 January 1900, Ladysmith; Private John Barry, KIA, 8 January 1901, Monument Hill; and Captain David Younger, DOW, 11 July 1900, Krugersdorp - were gazetted on 8 August 1902. The posthumous award of the Victoria Cross was now an acceptable course of action, but the debate over posthumous awards was not finished. The announcement of the awards prompted a call for fair play from outside the War Office and Horse Guards. Even before the London Gazette with their citations left the printers, word of the decision had leaked, prompting letters from grieving and in some cases irate family members demanding similar treatment for their fallen sons (PRO File WO/32/ 7498. Memo from General Sir Ian Hamilton, 8 October 1902). Most were easily dismissed, but the six who had been gazetted as '...would have... if survived' proved to be more difficult, particularly when their proponents were members of the aristocracy.

The first blast came from Sir John Joscelyn Coghill, father of one of the fugitive heroes of Isandhlwana. He wrote a threatening letter to the Secretary of State for War on 3 August 1902. When he got no satisfaction, he called on the young officer's uncle, Lord Rathmore, to put further pressure on the administration. On 17 September 1902, Lord Rathmore wrote to the Secretary of State for War, St John Broderick, on the subject. He suggested that the government could hardly withhold the cross from those who would have earned it had they not died, and now that the interpretation of the warrant had been altered, there was no bar to granting it posthumously. It is apparent from the letter that he intended to get a VC for his dead nephew, no matter what the cost. If he had to force the government to grant the award to five other corpses, so be it. However, it was not as if he were going to bat for the other five specifically (PRO File WO/32/7498).

LIEUTENANTS MELVILL AND COGHILL, WHO LOST THEIR LIVES AT ISANDHLWANA ON 22 JANUARY 1879 WHILE TRYING TO RESCUE THE QUEEN'S COLOURS FROM THE AMAZULU (PHOTO: BY COURTESY, SA NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MILITARY HISTORY)

Broderick forwarded the letter to Lord Roberts along with a request for information on any other 'would haves'. The C-in-C informed the Secretary of State that only six such cases existed and voiced his approval of backdating the VCs of these 'would haves' on the condition that only those already gazetted as such would be considered. It is apparent in the letter that he could not in good conscience refuse the award granted to his dead son to those who had earned it in the past (PRO File WO/32/ 7498. Undated letter from St John Broderick to Lord Roberts, assumed to be mid-September 1902; Letter from Lord Roberts to St John Broderick, 27 September 1902).

Others in the administration did not share his optimism, among

them his military secretary, Ian Hamilton, who wrote in his memo

of 8 October 1902 (PRO File WO/ 32/7498):

'If we confine this to the above nine [a reference to the three Boer

War posthumous VCs and the six "would haves"] all will be well, but I

must say I have had misgivings about this business.

Until now it has been the laudable object of a commander to

write to the relatives of officers and men who have fallen in terms of

unmeasured praise. This could do no harm. [It] could serve as a basis to

no claims and was a certain consolation. Now either all this

must stop and a dead man must be measured by the same standard as a

living one, or else applications for posthumous decorations will be the

rule and not the exception.

The impossibility of arguing with the relatives of a dead man is well

shown by the intensely disagreeable and threatening tone of Sir J Coghill

in his letter to the S of S dated 3rd August 1902.'

Broderick shared some of Hamilton's misgivings, but approved the measure. 'Submit to the king and at the same time make it perfectly clear no one will be allowed to participate in the decision who is not one of these nine', he wrote on 9 October 1902 (PRO File WO/32/7498). Lord Roberts did not credit the apprehensions. When Hamilton questioned him a final time over the proposal he replied with a brief note: 'Carry out. I confess I do not share your fears...' (PRO File WO/32/7498. Lord Roberts. Instructions to Military Secretary [Hamilton], 12 October 1902).

Subsequent to the deliberations of Roberts, Broderick, and Hamilton, the proposal to grant the six pre-Boer War VCs was submitted to Edward VII on 2 November 1902. According to an undated memo by S Ewart, Military Secretary, the king refused to approve the measure on the grounds that it would provoke a flood of submissions from grieving relatives (PRO File WO/32/7499). The problem was that His Majesty had already approved the issue of posthumous VCs to the dead heroes of the Boer War, which left an awkward situation, with the War Office caught between the monarch on one side and adamant relatives on the other.

Another reason cited for the King's reluctance to backdate Victoria Crosses was that so much time had elapsed since the original acts. As Lord Knollys later explained in a memo to the War Office, written in November 1906, 'H M thinks that with two exceptions the acts of gallantry were so long ago that it would hardly be understood were the VC to be given to representatives of the deceased officers and men after a lapse of so many years.' (PRO File WO/32/ 7500). At some point in late 1906, however, the widow of Lieutenant Teign mouth Melvill wrote directly to the king, requesting that the VC he should have earned at Isandhlwana be forwarded to her as his next of kin. It was clear that she understood the importance of the award, despite the years that had passed since 1879.

Accordingly, the Crown requested further information from the War Office on 3 December 1906, regarding the particulars of Melvill's case. General Sir Arthur Wynne at the War Office used this opportunity to bring up the cases of the other five 'would haves', pointing out that there was no substantive difference between Melvill and any of the others, and that to grant one and not the others would be a great injustice. Edward VII decided, based on this information, to go ahead and grant the VC to the six - on strict condition that no other pre-Boer War claimants be considered under any circumstances (PRO File WO/32/7500. Query from Colonel Sir Arthur Davidson to the War Office, 3 December 1906; Letter from Sir Arthur Wynne to Davidson, 6 December 1906; Letter from Davidson to Wynne, 8 December 1906). On Tuesday, 15 January 1907, the six were gazetted. What the reasoning of the War Office, the bombast of Sir J Coghill, and the influence of Lord Rathmore could not accomplish, a widow's plea made reality.

Bibliography

C E Callwell, Small wars: Their principal

and practice (London, HMSO, 1906,

reprint by Greenhill Books, 1990).

M Chariot, Victoria: The young queen

(Oxford, Basil Blackwell Ltd, 1991).

L Creswicke, South Africa and the

Transvaal War, Vols II, V (New York, G P

Putnam's Sons, 1900).

B Farwell, Eminent Victorian Soldiers.

B Farwell, The Great Anglo-Boer War (New York, Harper & Row, 1976).

W B Pemberton, Battles of the Boer War

(London, B T Batsford Ltd, 1964)

H Smith-Dorrien, Memories of Forty-Eight

Years' Service (London, John Murray, 1925).

The Times of London, 26 June 1857.

Public Records Office (PRO), Kew,

London, PRO files WO/98/2, WO/98/3,

WO/32/7300, WO/32/7470, WO/32/7478,

WO/32/7498, WO/132/7499, WO/32/7500,

WO/32/7878.

The Hon Frederick Sherston Roberts (VC)

Frederick Sherston Roberts was born

at Uniballa, India, on 8 January 1872.

He lost his life and was awarded the

Victoria Cross for an attempt to save

the guns of the 14th and 66th batteries,

Royal Field Artillery, during the battle

of Colenso on 15 December 1899. The

VC was gazetted on 2 January 1900:

'The Honourable Frederick

Sherston Roberts (since deceased),

Lieut, Kings Royal Rifle Corps. At

Colenso, on the 15th December 1899,

the detachments serving the guns of

14th and 16th batteries, RFA, had all

been either killed, wounded or driven

from their guns by infantry fire at

close range, and their guns were

deserted. About 500 yards [457

metres] behind the lines was a donga,

in which some of the few horses and

drivers left alive were sheltered. The

intervening space was swept with

shell and rifle fire. Capt Congreve,

Rifle Brigade, who was in the donga,

assisted to hook a team into a limber,

went out and assisted to limber up a

gun. Being wounded, he took shelter,

but seeing Lieut Roberts fall badly

wounded, he went out again, brought

him in, With him went the gallant

Major Babtie of the RAMC, who had

ridden across the donga amid a hail of

bullets, and had done what he could

for the wounded men. Capt Congreve

was shot through the leg, through the

toe of his boot, grazed on the elbow

and the shoulder and his horse shot in

three places. Lieut Roberts assisted

Capt Congreve. He was wounded in

three places.'

Reference:

(Sir O'Moore Creagh and E M Humphris,

The VC and DSO, Vol I, p 112).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org