The South African

The South African

The Fliegertruppe of the Imperial German Army

An experiment in the colonies

At the beginning of this century it became clear that if extended military operations were to be conducted in Germany's two largest African colonies, South-West Africa and East Africa, the Schutztruppe (German colonial army) would need more than merely ground-based reconnaissance. With this in mind, a number of interested groups examined whether Luftfahrzeuge (aircraft) might be used profitably in these territories. From 1905 the Kolonialabteilung des Auswärtigen Amtes (Colonial Department of the Foreign Office) received a number of proposals, the best of which emanated from the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft in Berlin, who suggested that tests be conducted on a steerable balloon in German South-West Africa. This resulted in dialogue and exchanges of memoranda between the Kolonialabteilung, the commander of the army airship battalion in Germany, Major Gross, and the army inspectorate of transport, who voiced their doubts about the technical viability of using airships in foreign countries under vastly different climatic conditions and without any home-based mechanical backup system.

Count von Zeppelin (1860-1924), the inventor of the dirigible airship, had by then built and flown a number of his constructions. However, these were plagued by accidents and an inability to perform successfully for an extended time-period, especially in bad weather. Common sense, therefore, dictated that it was too early to consider airships for adventures in the tropics. In addition, certain government departments were also not in favour of the idea, recommending monetary restraint.

In February 1911, a proposal was handed to the Kolonialabteilung and the Post Office for the introduction of air routes for an improved mail service in East Africa. The memorandum was entitled: 'Suggestions to improve links in German East Africa for postal, political and military purposes with the support of aircraft'.

The author was Dr Weiss from the Kolonialabteilung who had received a report from telegraphist Willy Lenk on using aircraft for postal deliveries. He suggested three air routes linking railways and harbours in the colony, as well as the major stations and European settlements. Wright aircraft should be deployed. Along with ground stations, they would be equipped with wireless for direct communication. But neither department was convinced, and it was even disputed that aircraft were a suitable method of transport in the thinly populated and arid regions of German East Africa.

However, with the French erecting a military airfield near Algiers in 1911, Italy deploying eight aircraft during their Italo/Turkish War in Syria (Tripolitania), and the governments of the Union of South Africa and Madagascar showing interest in air transport, colonial circles in Germany were inclined to revive the debates. These took place in April 1911 and a plan was formulated to send air force officers to German East Africa. A stipend from the Kolonial-Technische-Kommission to the Kolonialabteilung was to be used to train two suitable officers as pilots. East Africa had been chosen in favour of other colonies. The general opinion was that 'South-West has too many storms and unsuitable ground conditions; New Guinea is almost covered by jungle; Togo and Cameroon present too many obstacles through surface structure, cover and adverse climatic conditions, and there is no Schutztruppe contingent in Togo.'

In the meantime, considerable interest in aircraft was shown in South-West itself. One of the initiators was Oberleutnant Eckard Berlin, commander of Verkehrszug 2 (armoured train) in Keetmanshoop, who had been involved in aviation for the past two years. He considered aircraft to be the best vehicles for scouting duties in remote regions. In his opinion the objections raised by the Kolonial-abteilung were invalid.

The commander of the Schutztruppe, an acknowledged authority on the country, Major Joachim von Heydebreck, also expected great benefits by employing aircraft. His report, detailing the advantages and submitted through the command of the Schutztruppe, arrived at the Kolonialabteilung at the same time as a memorandum from the Great General Staff commenting on the growth of aviation in the French colonies. Nevertheless and despite all prodding, the Kolonialabteilung continued to insist on constraint, and in 1912 merely gave permission for Oberleutnant Berlin to be trained as a pilot while promising to obtain a stipend from South-West for the training of a second officer. These were the first tentative steps to introducing aviation in Germany's colonies.

A few months later, however, the Staatssekretär der Kolonialabteilung (Secretary of State for the Colonial Department), Dr Solf, changed his opinion and admitted that if Great Britain, France and Italy had successes with aviation in their colonies, then there was no reason why tests should not succeed under similar conditions in German colonies. He believed that aircraft were useful for conveying messages, for postal deliveries and for map surveys.

Reichstag and Reichsschatzamt (Parliament and Treasury) were of entirely different opinions. While one insisted on scaling down the Schutztruppe below an acceptable level essential for the protection of the colony, the other refused even to consider financing tests. To weaken the Treasury's argument, it was crucial to prove that aircraft could indeed fly in the colonies and, if the state refused financial help, then private initiative would have to take over.

The Grand Duke Adolf Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a foremost patron of German Civil Aviation, and Dr Ebermaier, Governor of Cameroon, both promised to raise money for this project. It was an endeavour destined to lead to disappointments. There were quarrels between the Treasury, the curators of the Nationalflugspende (national air charity) who had accepted donations, and the Kolonialabteilung. Party-political, bureaucratic and professional jealousy played a part and in the end only a half-baked settlement was reached. Money was made available to the Schutztruppe in South-West, but only for 1914 and in the view of many, this was too late.

In South-West itself, the Deutsch-Südwest-afrikanischer Luftfahrerverein (German South-West Africa Aviation Club) had been founded in Keetmanshoop in 1912 to promote the use of aircraft and airships in German colonies. Originally, the society had sixty members, but it grew quickly and by 1913 had established itself in a further ten towns, including Windhoek and Swakopmund.

Meanwhile, other European powers made considerable strides in Africa. France maintained aircraft squadrons in Algiers and Morocco, Madagascar used aircraft for urgent postal deliveries, and Belgium was ready to use float-planes on the Congo River. Even South Africa considered a similar float-plane project for Port Nolloth.

Although civilian authorities asked that the Schutztruppe be equipped with aircraft, with the Kolonialgesellschaft (colonial society) appealing for funds to 'establish land and water-based aviation in the African colonies without delay', the Treasury refused to act. It feared censure from a parliament hostile to any military expenditure. Only the Kriegsministerium (War Ministry) was sympathetic and promised to support tests by allowing officers to take part. But this was not enough and forced the Kolonialabteilung to put plans on hold once again.

Hauptmann Lutter from the Schutztruppe command in Germany changed all this, and the Governor, Dr Theodor Seitz, gave permission for the immediate shipment of two aircraft to the colony. The Nationalflugspende allocated an amount of 30 000 Mark to South-West for purchases - the exact price for one aircraft. The trial period was limited to three months, and flights had to take place at Karibib and Keetmanshoop, where workshops and technical facilities could be utilised. Credit must also be given to Oberleutnant Konrad Pueschel from the Schutztruppe police force. From 1911, he had championed aviation in the colony after obtaining his pilot's licence in Germany.

Bruno Büchner

In the meantime, a privately financed veuture by a businessman had taken off. It had no military aims but was to promote exhibition flights by Flying Instructor Bruno Büchner and to rally interest in aviation in South-West. He was given a biplane from the Pfalz-flugzeugwerke, caller Doppelfalz, and told that after completing his displays in South-West, he was to fly overland to East Africa to give shows there. In May 1914, Büchner, his wife, and a newspaper reporter arrived in Swakopmund with the Doppelpfalz. He assembled and tested the plane at the coast and flew to Windhoek. Conditions were far from ideal - the air was too thin at that altitude and the aircraft was outdated. It was therefore decided that Büchner should not continue to East Africa overland. He performed at a few shows in the south of the South-West colony and undertook what was, for those days, long distance flights to Usakos and Karubib, carrying post bags and even a passenger. These trips were not without danger and wind turbulence forced him to undertake unplanned stops, interrupting his schedules. He also held demonstrations at Keetmanshoop, Okahandja and Rehoboth. Eventually, the party arrived in Lüderitz by train.

The shows were much appreciated by local audiences who willingly paid for tickets. They continued until July when Buchuer had his plane crated and shipped to Dar-es-Salaam because the Union Government had refused to grant him overfly rights. Still, his displays demonstrated that aircraft could play a prominent part in the development of colonies.

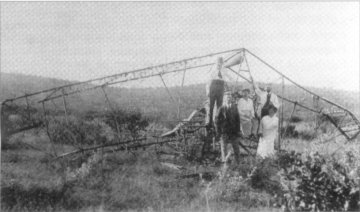

Büchner heard about the outbreak of the First World War in Zanzibar Harbour. He returned to Dar-es-Salaam and, on the open sea, met up with the battle-cruiser Königsberg. On arrival, he offered his aircraft to Oberstleutnant Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the commander of the Schutztruppe. Von Lettow-Vorbeck ordered Büchner to undertake a scouting mission in the direction of Zanzibar and Bagamoyo. Flying along the coast, he spotted two gunboats which immediately opened fire. He was wounded in the arm. On landing, the plane struck deep sand and somersaulted. Büchner was thrown clear, but injured, and late in the evening he arrived at his base, utterly exhausted. While he was still in hospital, another Schutztruppe officer, Leutnant Henneberger, had the plane repaired and took off. However, when he was attempting to land, the aircraft clipped the tops of palm trees and crashed. The pilot was pulled out dead from the only lightly damaged plane.

After his recovery, Büchner was ordered to fit floats to his plane and to support the Königsberg, which was then lying disabled in the Rufiji Delta. The aircraft was rebuilt and sheet-metal floats were attached. It was then found that there was insufficient petrol available, and the project was cancelled. The inventive Büchner fitted the aircraft's engine to a small-gauge railway goods truck and, with this much admired Schienen-Zepp (Rail-Zepp[elin]), undertook two goods transport trips to the inland town of Morogoro. Following the occupation by the British, Büchner and his wife were interned.

Military pilots in German South-West Africa

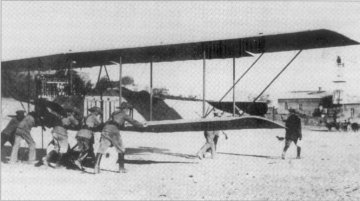

The first military pilot to arrive in Swakopmund in May 1914 was Leutnant von Scheele. He was accompanied by factory pilot Trück and four Schutztruppe NCOs who had been trained as aircraft mechanics. His plane, an Aviatik BI, docked two weeks later. A second plane landed in early June. It was a Roland-Stahldoppeldecker (Roland-Taube) built from steel. It was deemed to be especially sound for service in the tropics, and the pilot was Leutnant (2nd Lieutenant) (res) Fiedler.

Both planes were equipped with the latest type of compass and a signal-mirror for emergencies with a range of 30 to 50km in the 'clear air of South-West'. Provisions, water bags, tents, a rifle with ammunition, and tools were also provided.

Despite these results, von Scheele reported negatively on the Aviatik's performance. He argued that in 1913 in Germany, officers had refused to fly the plane because of its outdated engine, and that the army had not even considered buying the Roland-Taube, (the second aircraft) on account of its low rate of climb. But the Reichskolonialamt replied that no additional funds were available to buy anything better, and that they had to be grateful that manufacturers were willing to share the cost of the tests.

The assembly of the Roland aircraft took a long time. Technical problems plagued the tests and in late June the aircraft crashed, possibly due to its low rate of climb. Fiedler was slightly injured and the craft badly damaged. During that time, two German planes arrived in Duala, Cameroon, but unfortunately pilot and mechanics were still held up in Germany. Thus, when war was declared shortly afterwards, the planned air operations had to be cancelled. In March 1915, both crated planes were shipped to Cape Town on a captured German freighter, the Edna Woermann. One plane was assembled and exhibited, but it disappeared, reason unknown.

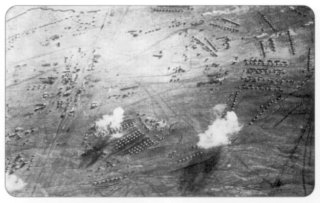

On 9 September, Leutnant Fiedler arrived in Karasburg with his repaired plane, complete with five mechanics/helpers, and began scouting. Of special importance was the built-on camera with which the photo-amateur Fiedler took numerous excellent pictures of enemy camps and positions. On 26 October, Fiedler flew to Steinkopf, (75km southwest of Ramansdrift), where he discovered a tent camp which he photographed. He was, therefore the first German flyer to cross into Union airspace. On the return trip, he had to make an emergency landing in Aus, but arrived back in Warmbad the next day.

When South African troops landed in Lüderitz in September 1914, von Scheele relocated to a new base at Aus on 6 November and six days later undertook a three-hour-long scouting trip to Lüderitz to obtain details of enemy positions. Two weeks afterwards he visited the camp again, but this time he carried bombs which he dropped on tents. This skirmish left the plane with fourteen bullet holes in the body and wings. During his third flight to Lüderitz, von Scheele scattered a few hundred leaflets of a proclamation by the insurgent Boer generals, calling Boer people to fight for freedom against the British, and on the return leg dropped a few bombs on an infantry camp at Rotkuppe (35km east of Lüderitz).

On 6 December Leutnant Fiedler joined von Scheele in Aus, and on 17 December they bombed the South African camp at Tschaukaib, 70km east of Lüderitz. He repeated the attack three days later, with von Scheele following on 4 January 1915.

On 19 February, the South Africans captured the important waterhole of Garup and erected a camp. Fiedler again dropped bombs and rifle grenades under heavy enemy fire. His photographs gave a very accurate record of the enemy's strength. Further attacks were made against Garup on 23 and 27 March and bombs were dropped 'with excellent results on the enemy camp and among the approximately 1 700 cavalry horses. This created frightful confusion'.

Two days later, Fiedler made a last flight from Schakalskuppe and reported that enemy patrols had already entered the mountains near Aus. A short time later, the village fell to the South Africans and Fiedler was ordered to fly north and join von Scheele.

Von Scheele and his Aviatik had not been lucky. The plane was ready to fly by 19 January, but as he took off for a scouting trip to Arandis, the radiator burst, forcing him to make an emergency landing. When the radiator had been repaired, it was discovered that the piston rings were worn. And so it went on. Spares were running out and the aircraft was showing its age. It was only in early April when von Scheele, promoted to Oberleutnant, could take to the sky again, this time to bomb the enemy camp at Arandis. One week later both aircraft started out for a reconnaissance trip to this camp. Despite enemy fire, von Scheele attacked it with bombs and rifle grenades, while Fiedler carried on to inspect a field camp at Roessing. He returned via Khangrube, Jakalswater and Ubib to Karibib. The trip lasted three hours. Eventually on 17 April, Fiedler's luck ran out. He crashed in the Swakop valley from a height of 30m and was taken to hospital with a broken skull. His aircraft was a mangled wreck.

On 19 April, von Scheele made a three-hour flight to Ubib, Jakalswater and Riet, and along the Swakop valley to Goanikontes. On the way back, he again bombed Arandis. Four days later, he was on a scouting mission for the Schutztruppe, which planned to attack Trekkopje, when he came upon a train at 81 km. He was spotted and the train tried to escape to Trekkopje under full steam, but he closed up, dropped his bombs on two companies there and returned to Usakos with only slight damage by rifle fire.

His following visit to Trekkopje was cut short when an anti-aircraft gun, which had just arrived, fired fifteen rounds at him. He prudently elected to break off the attack and returned to base without having dropped his bombs. The battle for Trekkopje ended in defeat for the Schutztruppe and on 1 May von Scheele received the order to bomb the camp. He was unable to complete this assignment, as the engine cut out over the Khan mountains near Stingbank. He managed to land close to the Omaruru railway line at 125km and, fortunately undisturbed by the enemy nearby, had his plane loaded and railed back to Omaruru.

By this time, the Aviatik was in really bad shape. When South African troops captured Windhoek on 12 May and advanced north, with other units crossing the Namib from Swakopmund, it was decided to send the aircraft to safety on a site near Otjiwarongo where a landing strip was built.

Von Scheele's final assignment began on 26 May when he was ordered to reconnoitre around Okahandja. When he took off from his stop-over at Kalkfeld, he crashed and was injured and taken to hospital. The aircraft was destroyed and the Schutztruppe effectively without any assistance from the air. This was von Scheele's eighth crash, and his fourth with injuries.

In the meantime, the railway workshop had been moved from Usakos to Tsumeb and had begun to repair the Roland biplane. At the end of June, the plane was ready, but a recovered Fiedler was not given an opportunity to fly again, as the Schutztruppe and the colony capitulated on 9 July 1915.

When taking into account the mechanical state of the two aircraft, the technical setbacks, adverse climatic conditions, the delays through crashes and pilot injuries, the saga of these aircraft is indeed one of determination, courage and an outstanding achievement in the military sense.

The remains of the Aviatik were dropped into the Otjikoto Lake, and the Roland was concealed in the bush outside Tsumeb. In 1916, two mechanics salvaged the Roland's engine and propeller, but burned the rest. OberLeutnant von Scheele was discharged from hospital in early July, but by then the campaign was over and he was taken prisoner. When he refused to give his word of honour not to escape, he was interned.

Whereas Zeppelins were not directly involved in the colonies' battles, there was the daring and exceptional operation by Navy Airship L59 under KapitanLeutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Ludwig Bockholt. On 21 November 1917, it left its base at Jamboli in Bulgaria with fourteen tons of weapons and medical supplies for delivery to the forces of General von Lettow-Vorbeck, who continued to hold out in the Makonde Highlands in East Africa against much stronger British forces. The 5 800 km trip, estimated to take between four and five days, across a trackless void under a blistering sun, was considered nearly impossible. A return flight was not expected. The crew was plagued by headaches, hallucinations and eye fatigue. They were dangerously rocked by hot-air currents and were also well aware that any mishap would leave them stranded, without any hope of rescue, in wild and hostile territory controlled by the British, if by anyone at all.

In the early hours, of 23 November, 200 km west of Khartoum, they received a recall from Berlin, saying that von Lettow-Vorbeck had surrendered. (The intelligence was wrong - von Lettow-Vorbeck held out until the end of the war in 1918). Reluctantly, Bockholt returned and landed at his base after 95 hours and 6 700km of non-stop flying. So ended one of the brilliant Zeppelin epics of the First World War.

Günther Plueschow

The most colourful career of any pilot serving on an overseas station must surely be the one of OberLeutnant (First Lieutenant Navy) Günther Plueschow. Ordered to travel to the German leasehold of Kiautschou in South-West China in June 1914, he arrived there by train in the main city of Tsingtao, while his two Rumpler-Tauben came by ship in July. The small airfield was the only suitable piece of flat ground in the colony. It was 600 m long and 200 m wide, and was surrounded by rocky outcrops. Take-offs and landings required great skill as the pilot was faced by sudden crosswinds and up or down drafts depending on the time of day. For a full day, Plueschow practised, until he was satisfied he could handle his plane. Then he and another pilot from the Seebatallion (marine battalion), Leutnent Muellerskowski, assembled the second Rumpler-Taube. But the second pilot was not as fortunate when he went up for his test flight. He crashed, was badly injured, and his aircraft totally wrecked.

On 15 August, the Japanese sent an ultimatum demanding a handover of Kiautschou, which was rejected by the Governor. At that moment Plueschow returned from a scouting trip. His engine cut out as he descended from an altitude of 1 500 m to about 100 m above the airfield. On both sides were buildings, and his only hope was to set the plane down in a bit of forest ahead. This he did and the plane was damaged. But pilot and engine were unharmed.

Repairing the aircraft was a heart breaking job and took nine days. The spare wings had disintegrated in their zinc crates and the spare wooden propellers were no better. A new propeller was made from laminated wood by Chinese carpenters; it made 100 revolutions less than required, and had a tendency to come apart on each flight. But at least Plueschow could fly, and supply the Governor with valuable information about the enemy.

Early in September the Japanese intensified the siege. Plueschow received small arms fire and warship shrapnel, and from then on was forced to keep above 2 000m. From 5 September, the attackers sent up to eight aircraft to attack the defences and the airfield, among them four very large biplane seaplanes. One of the planes attacked the unsuspecting Plueschow in the air, but without result. A few days later he was wide awake during an encounter and downed an enemy with 30 shots from his parabellum pistol.

The Japanese bombardments gradually destroyed the defensive positons, and Plueschow's aircraft, parked under cover, was then only 4 000 m away from enemy guns. Having anticipated this problem, Plueschow and an Austrian pilot, Leutnant Clobucz, had built a twin-wing seaplane in the harbour dock which, on 5 November, was ready for its first test flight. But the Governor ordered Plueschow to fly out of Tsingtau when, two days later, the city fell to the Japanese. Plueschow took off and, after covering a distance of 250 km, plunged into a rice paddy. He set fire to his plane, and then began an extraordinary voyage that led him halfway around the globe, ending in a POW camp in Britain. He escaped, and arrived back in Germany in July 1915. Plueschow reported to the Imperial Navy Staff and was decorated with the Iron Cross 1st Class, promoted to KapitanLeutnant and commander of seaplane station Libau on the Russian front.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org