The South African

The South African

War experiences of a youngster in South Africa, 1939-1945

The l930s were turbulent years. At a young age, I heard accounts of the invasion by the Italians of countries in northern Africa and the name of Hitler linked to bad things. During this time, family members would reminisce constantly about their awful experiences of the First World War (1914-1918), spreading gloom and doom as they thought of the future, expecting another war. At the age of ten, when I was a pupil at the Heidelberg Public School, a small English school in that town, my father died. He was a veteran of the Anglo-Boer War, having served as a trooper with the Fifth South Australian Contingent during that war. I boarded with a Boer family named Badenhorst. The husband, Ian, had fought against the British in the Anglo-Boer War, while the wife, Lettie, had experienced the trauma of life in the concentration camp in Heidelberg.

By listening to their stories, I learned of the horrors of that war. I became very worried about what would happen in the coming days as the threat of a new war drew closer. My mother set up home in Braamfontein, a suburb of Johannesburg. It was while spending a weekend at home with my family that, on Sunday, 3 September 1939, I heard over the wireless the British Prime Minister's declaration of war against Germany.

The population of Heidelberg was predominantly Afrikaans-speaking, and many were anti-war in sentiment. The minority English and pro-war groups in the town were subjected to verbal and physical abuse. The Ossewa Brandwag in Heidelberg took an increasing militant stand against the war effort and openly exhibited their support for the Nazi cause. Acts of sabotage took place in the town and some of the buildings housing English-speaking organisations were damaged by explosions. Attempts were also made at blowing up bridges on the main Durban road in an effort to disrupt military convoys en route to the coast and other towns.

Because of the divided feelings of the South African population, recruitment for the armed forces was restricted to volunteers. The Steel Commando brought all types of military vehicles manned by soldiers to Heidelberg to demonstrate different types of weapons to the public and to call for recruits. As a result of this effort, a good proportion of the members of pro-war groups volunteered for active service. For us youngsters, clambering over the armoured cars, guns, troop carriers and other military hardware was a very exciting experience. After visiting Heidelberg, the convoy continued on its recruiting drive through the rest of the country.

I was a member of the Heidelberg Boy Scout Troop which, being English-speaking with allegiance to the King, was not warmly accepted by the anti-war group. The troop consisted of twenty boy scouts and it had a band of one drum, two bugles, and three flag bearers to carry the Scout, Union of South Africa, and Union Jack flags during marches. When marching through the town on route marches and attending church parades, the band would make much noise, the flags flying and the rear marching smartly and this display would rile the anti-war group. The Scouts received community-based training to provide assistance in the event of any disturbances.

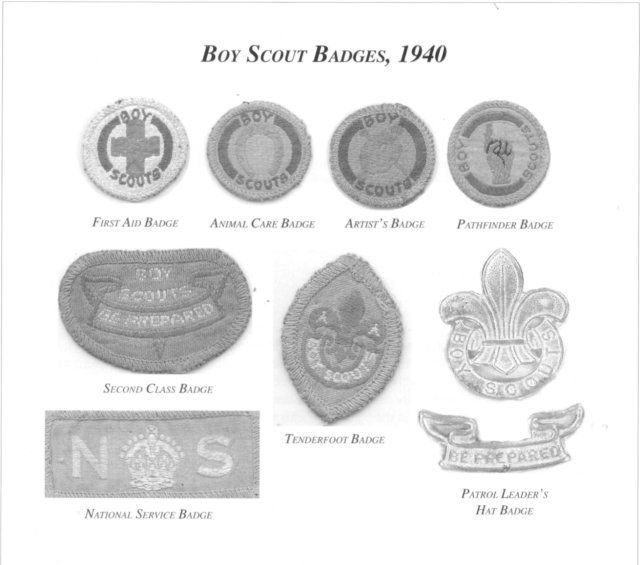

The Scout Movement, eager to help in the

war effort, introduced its 'National Service'

badge in 1940. To qualify for this badge, a scout

was required to pass the following proficiency

badges:

My stay in Heidelberg came to an end in December 1940. It had been a good experience in that I had learned how people with different points of view had reacted to each other within the context of war. Back in Braamfontein, I soon became aware of another divided community, where some made an effort towards ensuring a better life while others were not concerned about which way the war went. In this atmosphere, I was faced once more by anti-war organisations. Jewish shops in the area became targets for bombing attacks, which in some instances resulted in severe damage. Dark service lanes between the houses afforded gangs ideal places from which to launch assaults on soldiers and other victims.

In 1941, at the age of thirteen, I was enrolled as a trainee fitter and turner with the Johannesburg Technical High and Trades School, a branch of the Witwatersrand Technical College. The school, which taught academic and technical subjects, offered training in the following trades: Aeronautical Mechanics, Fitting and Turning, Electricians, Motor Mechanics, Plumbing, Blacksmithing. Woodwork, and Boiler Making. Because of wartime requirements, pupils were trained in the workshops during the day, while on a night shift basis the premises were used for training members of the relevant armed forces of South Africa and other parts of the British Empire in trade skills. This type of arrangement led to the establishment of the Central Organisation of Technical Training (COTT) at various centres throughout South Africa. After two years of training, I passed the practical tests in fitting and turning with the required proficiency and was delighted to be chosen to do war work. I became involved in producing precision spare parts for the military forces up North.

All pupils at high schools were required to take part in cadet training. The cadet detachment of the Trades School was unique in that not only was it allied to the South African Air Force, but it had also received regimental colours from the Governor General of South Africa, Sir Patrick Duncan, in 1938, making it one of the few detachments in the British Empire to receive such an honour. The uniform consisted of a short sleeved khaki shirt, khaki shorts held up by a broad leather belt with an ammunition pouch, school coloured socks with black shoes, an Air Force forage cap with the South African Air Force badge, and the WTC (Witwatersrand Technical College) badge worn on the shoulder. Cadet training consisted mainly of parade drilling and musketry for which each cadet received five rounds of .22 ammunition for target shooting practice once a month.

The news of the Springbok armed forces' victory over the Italian army in East Africa was received with tremendous jubilation in South Africa and lifted the morale of the folks at home. It spurred everyone on war work to renewed efforts as they became increasingly aware of their part in the bigger picture. Individuals such as Dan Pienaar, Jack Frost, Kershaw and others became heroes in the minds of us youngsters. During this time, the South African forces moved on to the Westem Desert, where they were to become part of the British Eighth Army. In November 1941, we heard how, in an offensive against the Axis forces, the 5th South African Brigade fought an heroic battle at Sidi Rezegh, only to be overrun by overwhelming Axis tank forces. The casualties were enormous and touched the homes of many bereaved families.

Back at home in Johannesburg, soldiers from all parts of the world were to be seen on the streets of the city, entertainment was lavish and the bioscopes were full. We youngsters were highly amused when the usual earth tremors we felt from time to time would cause many of the overseas soldiers to run out of buildings, believing a bomb had exploded.

The loss of the 2nd South African Division at Tobruk in mid 1942 led to the training of cadets in the use of weapons of war such as 25-pounder guns, mortars and Bren guns, in signalling and in providing medical assistance. I was a member of a mortar squad and we were trained by very stem permanent force instructors. Any lapse of discipline resulted in holding a 25 kg mortar base plate at chest height while running around the parade ground - a tough punishment for a fifteen year old cadet. Besides undergoing strenuous weekly drill training, cadet detachments participated in war time parades. On 26 June 1943, we took part in the huge 'Unite for Victory' parade in which 20 000 members of infantry and mechanised units and civilian organisations marched past General Smuts, who took the salute.

During the war, several hundred young evacuees sailed from Britain to South Africa and were fostered by families throughout the country. I shared my class at Trades School with one of these children. Having experienced the full horror of the German Blitz on London, which had caused the deaths of both his parents, we were always aware of his sadness and did all we could to help him to adjust. With time he became a brilliant pupil. His experience brought home to us the realisation of how very fortunate we were to be so far away from the direct war zones.

Owing to financial constraints, I left Trades School at the age of sixteen years. Still too young and with some medical problems, I was not able to join up, but took up the position of an apprentice fitter and turner in 1944 with African Films Ltd, the company responsible for maintaining bioscope and entertainment venues around the country. Entertainment equipment was also manufactured for use in the north African and Indian theatres of war. Most of the bioscopes and theatres in the bigger towns were equipped with organs and the very eloquent Colloseum Theatre in Johannesburg had a full symphony orchestra conducted by Charles Manning. During all performances, time was allocated for musical interludes of stirring and patriotic tunes with the audience joining in with enthusiastic singing.

In those times, Saturday was a working day. As an apprentice, I received a small wage per week. After paying for board, education, and transport, a little was left over for entertainment. With this money, one could afford a mixed grill plus a bioscope show, leaving a few coins.

After the D Day invasion, the Germans were being driven back on all fronts and victory seemed imminent. The demand for war supplies and food began to escalate, causing shortages of some commodities amongst the civilian population. Rationing was thought of but never implemented as a means of solving problems such as the Smuts bread loaf and very long meat queues.

When news reels of the ghastly scenes of the Nazi-controlled extermination camps were shown at bioscopes, feelings of unbelievable disgust and hatred were evoked. Shrieks of horror added to the grim atmosphere and many people fainted and collapsed.

A youngster not in uniform during the war years did not have an easy time. On the one hand, he would be subjected to abuse from the anti-war group for his pro-war attitude while, on the other hand, he was likely to be given a white feather from the pro-war group who assumed he had anti-war feelings. As there was no solution to this problem, one simply had to grin and bear it.

Driven back on all fronts, the German Army faced utter destruction and in April 1945 the German High Command surrendered unconditionally to bring the war in Europe to an end. There was great elation throughout South Aflica and families all over the country were very excited about the prospect of the imminent return of their loved ones. The Japanese war ended a few months later with the dropping of the atomic bomb, a powerful and destructive new weapon, the implications of which were beyond comprehension at the time. The war was over and although it was a horrible event, the experiences which I had during the war years brought about a maturity in the way I thought and acted.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org