The South African

The South African

'Die bekendste hendsopper en joiner van almal.'(1)

The most famous 'hendsopper' and 'joiner' of them all

Mark Coghlan

Military Historian, KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Museum Service

and Regimental Historian, Natal Carbineers

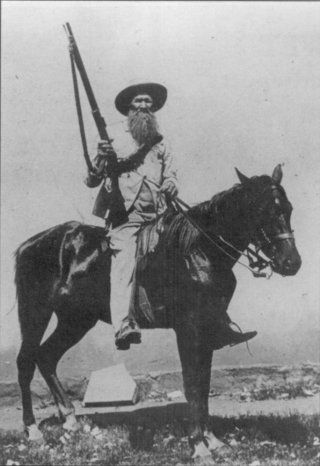

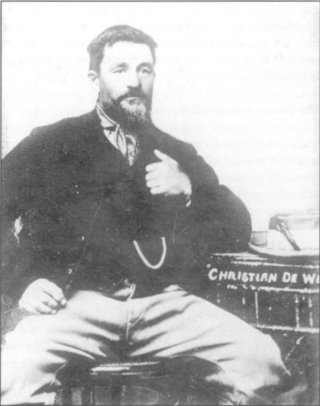

Piet de Wet (From Emanoel Lee, To the bitter end, p 124)

The above extract is arguably the popular and lasting impression of the Boer fighter and military leadership during the Anglo-Boer War, typified by the dash and tenacity of General Ghristiaan de Wet. The story of his brother, Pieter Daniël de Wet, as notorious in Afrikaner folk memory as Christiaan was famous, and at one time an assistant commandant-general of the Free State Army is, however, a very different one. For most of the estimated 17 000 burghers still in the field towards the end of the war - the 'bittereinders' - the British annexations had not ended the war and the authority of the Crown was therefore illegitimate.(3) Many more had ceased to be combatants, but such 'neutrality' was tolerated. However, the same cannot be said of the 4 000 to 5 000 who actively served with the British forces. In the view of Bill Nasson, 'the quandary of a hard-pressed Boer society deepened as a flank of its anti-imperial war began to mutate into a bitter head-on civil war.'(4) The hero-worship of the Boer generals in the Christiaan de Wet and Koos de la Rey mould, and the demonisation of 'joiners' such as Piet de Wet, was prevalent as late as 1990, when Jacques Malan published his biographical compilation, Die Boere Offisiere 1899-19O2.<(5) If the level of hostility towards alleged collaborators from the 'bywoner' (tenant) class is anything to go by, the reaction from more elevated backgrounds can well be imagined. Writing in 1985, Emanoel Lee says of the collaborators: 'Amongst Afrikaners they are remembered to this day with such hatred that it is almost impossible to get any information about them.'(6)

(Source: C Pama, Die Groot Afrikaanse Familienaamboek)

Piet de Wet was born on 18 August 1861 on the farm 'Nuwejaarsfontein' in the Dewetsdorp district of the Orange Free State. Seven years younger than Christiaan, he was one of fourteen children of Jacobus Ignatius and Aletta Susanna Margaretha de Wet. Although Piet received little formal education, as was the norm on the Free State platteland at the time, he was reportedly intelligent and showed a flair for languages.(7) In 1879, he and Christiaan left home to farm together in the Heidelberg district of the Transvaal. At this point, they apparently shared a close relationship with each other and, on 8 December 1880, they jointly attended the historic Boer gathering at Paardekraal, where it was resolved to cast off the British annexation of 1877. This was followed by active commando service in 'die Eerste Vryheidsoorlog' and the climactic battle of Majuba on 27 February 1881.(8) In 1882, Piet de Wet also saw service in one of the perennial Boer campaigns against black chiefdoms; in this case, the Mapoch War against Chief Nyabêla.

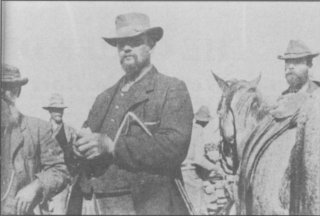

(The archetypal figure of the steadfast mounted burgher

(Source: Siege Museum, Ladysmith)

(Piet de Wet on commando

(Source: J H Breytenbach, Geskiedenis van die Tweede

Vryheidsoorlog, IV, between pp 258 and 259)

Piet de Wet's wartime commando service

At the outbreak of war, Piet de Wet was in command of 200 burghers attached to the Bethlehem Commando, who were despatched to the Natal front. He led his men with distinction at the Boer victory at Nicholson's Nek outside Ladysmith on 50 October 1899. Thereafter, he was initially part of the siege cordon before being transferred to the western front (also called the southern front) in the southern Free State and the northern Cape.

Piet de Wet was instrumental in the Boer seizure of a British position at Vaalkop near Arundel on the auspicious day of 16 December 1899. On this occasion and others during the first six months of the war, De Wet was among the Boer officers urging the strongest possible pursuit and he railed against the aged Boer military veterans of 1880-1881.(16) In recognition of this action and of his service to that date, President Steyn appointed him to command all Free State commandos south of the Orange River, headquartered at Colesberg, with the rank of general. He was thus one of the first of the younger Free State burghers to be promoted to general. He immediately established a reputation for aggressive action, so much so that the British were compelled to shift the focus of their first offensive in the region westwards in the direction of the Modder River.

On 16 February 1900, De Wet received instructions from President Kruger to reinforce General Piet Cronjé, under pressure from Lord Roberts on the Modder River. En route to this assignment, he heard of Cronje's surrender with some 4 000 burghers at Paardeberg.

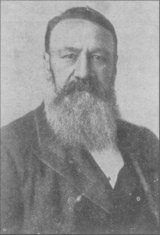

(Commandant-General Piet Joubert

(Source: H W Wilson, With the Flag to Pretoria, I, p37)

By mid-May, Piet de Wet found himself striking

sporadically at British columns in his home district of

Lindley.(23) By 18 May, Lindley had been proclaimed the

provisional capital of the Orange Free State, following the

fall of Kroonstad. It was a status it would enjoy only

briefly.(24) According to Thomas Pakenham, the De Wets'

hometown was not a very inspiring place:

'Lindley struck people as a depressing place. It was one

of those strange, bare little towns, whose presence on the

veld was so inexplicable: no visible roads led to it; no fertile

fields, let alone trees or gardens, surrounded it; it was just a

cluster of tin roofs and a bleak, tall church.'(25)

Winston Churchill's eyewitness report was more favourable: 'Lindley is a typical South African town, with a large central market-square and four or five broad unpaved streets radiating therefrom. There is a small clean-looking hotel, a substantial gaol, a church and a school-house. But the two largest buildings are the general stores.'(26) From mid-1900, the triangle of territory formed by Lindley, Bethlehem and Reitz was to form a reliable base of operations for Boer raids, especially by Christiaan de Wet, although before long little was left of the towns themselves.(27) At this point, Piet de Wet proposed a concerted head-on assault by all Free State forces on the advancing British army. His brother advocated an attack in the enemy rear by way of Norwalspont. This strategic difference of opinion was to be but the tip of the proverbial iceberg as far as the falling out of the two brothers was concerned, but, according to Grundlingh, it did suggest a more conventional approach to the conduct of war by Piet compared to Christiaan '5 unconventional flair. It was already apparent that Christiaan's approach, with its key element of surprise, was soon to be the only viable one for the Boer commandos.(28) Perhaps Piet felt himself threatened with marginalisation in military affairs.

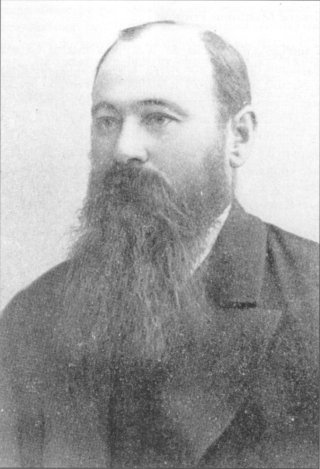

(President M W Steyn of the Orange Free State

(Source: H W Wilson, With the Flag to Pretoria, I, p 55)

General Marthinus Prinsloo

A similar story to Piet de Wet's was that of General

Marthinus Prinsloo, who served throughout the campaign

in Natal.(34) It was on 29 July 1900 that Prinsloo opened

negotiations for his surrender to the British. Like Piet de

Wet, Prinsloo's action also came as a shock at all levels of

the Boer military and political effort, but, according to P J

Delport, it was probably some time in gestation.(35) Generally

such efforts at surrender were complicated by the British

insistence on unconditional surrender.(36) It also emerges

from Prinsloo's case that honourable surrender after a good

fight was viewed in a commendable light in British circles.

Following his unconditional surrender, Prinsloo was asked to

'accept for yourself and all your men our sincere admiration

for your loyal and gallant conduct while acting against

us ...'(37) Prinsloo announced the surrender to his men in the

following words:

'Ik heb de eer aan U Ede en alle officieren en Burgers van

die krygsmacht onder myn bekendt te maken dat ik heden na

veele moeite over een gekomen ben met den bevelvoerder van

de Britse krygsmacht alhier om onvoorwaardelijk aan hem

over te geven ...'(38) (I have the honour to make it known to

Your Honour and all officers and burghers under my

command that, after considerable effort, I have reached an

agreement with the commander of the British forces to

surrender unconditionally.)

While Prinsloo's surrender was greeted with relief by some in his own command, it was greeted with outrage in other Boer quarters, not least because of the jubilation it elicited among the British forces - exactly the sort of propaganda that the likes of Christiaan de Wet would deplore.(39) To add insult to injury, when they surrendered, Prinsloo's men, nearly a thousand of them, were forced to ride through a two kilometre-long double row of British infantry, armed with bayonets, to a flagpole flying the British flag.(40) The location of the surrender, on a farm called 'Verliesfontein', became known as Surrender Hill.(41) The number of surrenders initiated on this occasion swelled to over 4 000. Most of these men landed up as prisoners of war in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) or India, while Prinsloo was held at Greenpoint near Cape Town.

The surrender was a heavy blow to the Free State.(42) Prinsloo's report on the matter to General Christiaan de Wet, the overall commander-in-chief of the Free State forces, elicited the blunt response that it was nothing less than a gruesome murder on government, land and people.(43) Another damning factor in the surrender of Prinsloo, and of Piet de Wet, was the fact that in mid-1900 the position of the commandos in the Free State was still relatively strong, a fact remarked upon by the British themselves.(44) Interestingly, Prinsloo also had a brother, General Michael Prinsloo, who, like Christiaan de Wet, took a very different path from his sibling.(45) One reluctant burgher who recorded his wartime experiences in a diary was Petrus Jacobus du Toit, who surrendered in May 1901 at Ventersdorp, and served in the National Scouts.(46)

The adventures of Christiaan de Wet

According to C J Barnard, Christiaan de Wet 'was the first Boer general who thoroughly understood the tactics of mobile warfare. It was his constant aim to avoid the superior forces of the enemy and then to strike quickly the moment his adversaries relaxed their vigilance.'(47) His daring tactics were demonstrated at Rooiwal in the north-eastern Free State in early June 1900, soon after the British capture ofthe Boer capitals and when the morale of the commandos was at a low ebb. Here his 8 000 burghers were hemmed in by British garrisons and cordons. Supplies carried by rail were essential to the British and one large depot was accumulated at Rooiwal, between Kroonstad and Vereeniging.(48) The booty of supplies captured at Rooiwal on 7 June was the largest of the war, and it was this sort of action that was to make De Wet's name a legend in South Africa and across the world, and rekindled the spirit of resistance in the republics.(49) This success had been achieved with a leaner but committed force of commandos that had effectively been disbanded in March 1900 with the instruction to reassemble after a period of ten days. De Wet, described at this juncture as grey-haired, curt and ruthless, had assured an incredulous General Piet Jouberr that those burghers who returned would be the most commitred, and so it proved.(50) His brother, Piet, was to take a drastically different course.

A change of heart for Piet de Wet

Despite his commendable war record, by May 1900 Piet de Wet was starring to exhibit reservations about the conflict and to lose confidence in the Boer prosecution of it. He was also pessimistic over the anticipated foreign intervention, a holy grail that was to prove elusive for the Boers.(51) Even his victory over the Yeomanry on 31 May did not inject a new personal enthusiasm.(52) In his defence, though, it must be said that the Free State forces in general were at a low ebb following the defeat at Paardeberg on 27 February and the subsequent British occupation of Bloemfontein.(53) Breytenbach writes that, in the wake of the fall of Kroonstad, the Free State commandos appeared disheartened: 'moedeloos huis toe gedros en geen lus meer geopenbaar om verder te veg [nie]' (disheartened, they deserted and exhibited no desire to continue fighting).(54)

Another factor worth considering is Piet de Wet's repeated references to the physical devastation and resultant human hardship that the war was visiting on the Boer republics. He was probably aware, for example, that homesteads had been targeted from the moment the British Army entered the Orange Free State on 11 February 1900. The burghers termed such destruction 'vernielzucht'.(55) Helen Bradford has suggested that, following the defeats of Black Week in December 1899, British policy became increasingly vindictive and that this occurred long before the onset of the guerrilla war. It resulted in 'a sort of Sherman's match through Georgia'.(56) One factor to consider here was that the British occupation of the Free State, and then the Transvaal, was 'probably the first occasion on which British forces undertook extensive occupation of territory as opposed to mere invasion'.(57) This was complicated by the fact that hostilities continued for two years after the commencement of the occupation.(58)

(Burghers sign the British oath of neutrality after surrendering, c 1900

(Source: Emanoel Lee, To the Bitter End, p 123)

'Go and fight. I can get another husband, but not another Free State.' Gender issues in the politics of collaboration

Bradford also makes the important point regarding the domesticity of the Boer male psyche. Many Boer leaders, and Piet de Wet would have been one, identified strongly with family and farm and were slow to identify with the concept of the nationalistic nation-state.(65) Perhaps Piet de Wet allowed these feelings to override his concern for the survival of the state more than the likes of his brother, Christiaan. It was the conviction of many an ordinary burgher, and not only leaders such as De Wet, that loyalty to family and hearth far superseded that owed to the state. Commandos melted away as many burghers were relieved to replace war for home and hearth.(66) In light ofthe above, Bradford makes the general point that 'the invasion of the Free State, and the almost simultaneous reversal of military fortunes throughout South Africa, greatly intensified reluctance to fight'.(67) Bradford specifically mentions Christiaan de Wet's exasperated response to the consequent crisis in Boer ranks: 'As commandos collapsed, De Wet, notorious for his machismo, with all its Boer inflections, granted home leave to every man. He could not corner a hare with reluctant hounds, he told his shocked Transvaal counterpart.'(68) Significantly, it was the determined resolve of De Wet's political chief, President Marthinus Steyn, that steadied a floundering Transvaal-Kruger ship in the wake of the fall of Pretoria in June 1900.(69) It was also in the southern Free State that renewed Boer resolve made itself felt with raids in the Jagersfontein, Philippolis, Fauresmith, Jacobsdal and Koffiefontein districts in late October 1900.(70)

Interestingly, habitual seclusion of Boer women on farms where hatred of the British was almost a fact of life, complicated by the inversion of established patriarchal gender roles under the pressure of war, left a hardened and resilient womenfolk very intolerant of signs of weakness such as surrender.(71) Renowned Boer fighter Roland Schikkerling recalled meeting one of these tough women on the Transvaal Highveld: 'She hated the English and all their innovations, and made me promise to whip them to the water's edge, and, as they were departing, to fling back into their ships their finery, their high-heeled boots, their corsets and all their hollow "pracht en praal" (pomp and splendour).'(72) It is probably fair to speculate that women like these would have fiercely resisted the collaboration of their menfolk with the British invaders. The result of all this was a remarkable resurgence in Boer resilience that probably accounts for the subsequent failure of surrendered leaders like Pier de Wet to recruit from the commandos.(73) Churchill's description of an episode in the occupation and almost immediate evacuation of Lindley in May 1900 also speaks volumes about the nature of Boer acquiescence to the British presence: 'All kinds of worthy old gentlemen, moreover, who had received us civilly enough the day before, produced rifles from various hiding-places and shot at us from off their verandas.'(74)

A falling out between the De Wets

A simmering tension between the De Wet brothers reached fever-pitch in June 1900 with a secret election in the field for the post of commandant-general of the Free State forces. A third candidate was Marthinus Prinsloo.(75) Christiaan de Wet emerged the victor from this contest, with his brother earning only a solitary vote, and Prinsloo two. The final break, of course, was to come with Piet's formal surrender and entry into service with the British forces.(76) The rift was to be permanent, and there was almost a brawl between the two when they met perchance in the Grand Hotel, Kroonstad, at the end of the war. In 1915, when Christiaan was languishing in Bloemfontein gaol for his part in the 1914 Rebellion, Piet entertained the futile hope that he could use the opportunity to clear the air between the two.(77)

One De Wet surrenders

On 19 July, Piet de Wet fought his last action on the side

of the Boers. Ironically, this was a joint operation with

subsequent Boer legend, Danie Theron, at Karoospruit

north of Lindley.(78) On that day or the following, he met

with his brother to discuss with him the prospect of

furthering the war. Christiaan dismissed him abruptly.(79)

According to Christiaan, who pointedly avoids any reference

to Piet as being his brother, the exchange went as

follows:

'We had the opportunity of accepting the invitation of

Mr C Wessels to take breakfast at his house. It was there

that General Piet de Wet came to me and asked if I still saw

any chance of being able to continue the struggle? "Are you

mad?" I shouted, and with that I turned on my heel and

entered the house, quite unaware that Piet de Wet had that

very moment mounted his horse, and ridden away to follow

his own course.'(80)

Without much further ado, General Piet de Wet and several members of his staff surrendered to the British at Kroonstad. Well, there was a little more to it than that: On 18 July, for example, he had exchanged correspondence with Lieutenant-General Ian Hamilton on this very subject, when the latter occupied Lindley.(81) Winston Churchill had been there. From a farmhouse about sixteen kilometres from the village, De Wet sent in a message to British cavalry commander Brigadier-General Robert Broadwood (whom he had helped to defeat at Sannaspost), offering his surrender, with a thousand burghers, on condition that he be permitted to return to his farm and not be exiled to Cape Town and perhaps overseas. His messenger was already on his way back with Broadwood's approval of this condition when this decision was overturned after hurried telegraphic communication with Lord Roberts.(82) De Wet therefore resolved to continue fighting, for the time being at least.

Another Free State general to voice his opposition to the war was J H Olivier, who had defeated Major-General Sir W F Gatacre at Stormberg Junction in December 1899. After his capture near Winburg in early 1900 he offered to maintain the peace in his district with his own commando, but the offer was refused.(83)

The peace committees in the ORC

Peace committees ('vredeskomitees') on a central and local level were established in both the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony (formerly the Orange Free State). This was an initiative by Roberts's successor, Lord Kitchener, in an effort to promote an end to the war. Their establishment represented 'the most sustained campaign of propaganda to that date to induce Boers in the field to lay down their arms'.(84) Piet de Wet played a major part in the context of the Free State committees.(85) He asserted that there existed among a certain portion of the Free State people a spontaneous 'pro-peace' movement, and by the end of December 1900 he was chairing the central Free State committee in Kroonsrad.(86) By May 1901, committees were established in Bloemfonrein, Harrismith, Bethlehem and Winburg.(87) According to SB Spies, 'Kitchener made it clear to these peace committees that they were not to discuss questions of policy. He wanted the burghers still fighting to be informed by men they could trust that Britain intended to see the war through and that there was no possibility of foreign intervention in South Aftica.'(88) He did not, however, expect too much from this initiative and it was not to yield much.

Kitchener, on the part of the British, shrewdly appreciated the political potential of encouraging division among the enemy - an 'if they can be made to hate each other more than they hate us' philosophy.(89) Piet de Wet was a case in point. However, efforts to persuade the British authorities to permit the involvement of such leading exiled prisoners of war as General Piet Cronjé on St Helena to return to help set up a united front among the Boers in favour of bringing an end to the war, failed. Kitchener refused permission.(90) An intensive propaganda effort was also mounted in late 1900, and contingents of 'wapenneerlêers' (those who had laid down arms) were despatched to the still active commandos. There was also an initiative in May 1901 by a former 'hoof-commandant' and Free State Volksraad member for Philippolis, E R Grobler, to secure a Boer surrender through constitutional means. This was, however, unsuccessful.(91)

Canvassing the commandos?

Efforts to canvas the active commandos to persuade them to surrender, and to secure recruits, was nor a success, 'On the contrary, they relieved the fighting burghers of worry with regard to their families, who would then be the responsibility of the British, and enabled them to continue the struggle without distraction,'(92) This initiative included proclamations from the British military authorities and letters from womenfolk to their men on commando.(93) In the case of the latter, the women in most cases, far from encouraging surrender, often urged the burghers on to greater efforts'.(94) Many ofthe passive 'handsuppers' who had surrendered fairly early on in the war often found themselves back on commando. For those who did so unwillingly, it was often due to British inability or unwillingness to guarantee their safety against active burghers.(95) The overall failure of the peace committees and this canvassing of the commandos contributed directly to the establishment of burgher corps to assist British columns in the field.(96)

A likely factor behind the failure of efforts by the

'hendsoppers' to attract support from commandos in the

field was the fluctuating morale of the burghers at this

crucial phase of the war (circa June 1900 to July 1901). At

the time of Piet de Wet's surrender, the situation of the

commandos was at a low ebb, but it did not remain so,

as the following extract from Life on Commando in the

Anglo-Boer War illustrates:

'During the guerrilla phase, self-interest and lack of

self-sacrifice, which had weighed so heavily at first, gradually

disappeared, resulting in a dramatic improvement in

military discipline. After four months on commando,

during which he commented several times on the lack of

self-sacrifice, Hintrager noted in September 1900 that the

main thing he had observed in the struggle was that many

Boers gradually started sacrificing their personal interests for

the good of their country and their people. Whereas in

June, many of them had been concerned mainly with

defending their own property, a sense of solidarity as a

nation of brothers at arms developed in the course of the

struggle. As this awareness grew, the Boer cause started

prospering.'(97)

Wartime life for Piet de Wet after his surrender

'Piet de Wet se vrywillige oorgawe het hom 'n onbeminde persoon by die lojale Republikeinse bevolking gemaak,.'(98) (Piet de Wet's voluntary surrender made him unpopular amongst the loyal republican population.)

In the first week of August 1900, De Wet travelled to Durban, where he remained for four months on parole.(99)

De Wet appeals to De Wet

On 11 January 1901, Piet de Wet appealed to his brother in an open letter to give up the struggle.(100) Piet tried almost everything in his arsenal of persuasion: The slim likelihood of European intervention; the prediction that the country would be left devastated if the war continued much longer; and the suggestion that the ordinary burgher was being misled by the Boer leadership and would wish to throw in the towel if the true situation was known. One message to his brother read as follows:

'Which is better for the republics - to continue the struggle and run the risk of total ruin as a nation or to submit? Could we for a moment think of taking back the country if it were offered to us, with thousands of people to be supported by a government that has not a farthing even if we received help from Europe? Put passionate feeling aside for a moment and use common sense, and you will then agree with me that the best thing for the people and the country is to give in, be loyal to the new government, and try to get responsible government.'(101)

This letter was published in the Bloemfontein Post on 11 January, and shortly thereafter appeared as a booklet entitled Broeder tot broeder: Een prijzenswaardige brief: Een smeekstem tot De Wet. Piet also claimed in this letter 'that he had openly discussed surrender with his brother and President Steyn and that he was therefore no traitor'.(102) Christiaan was apparently unmoved and his only recorded response to the appeal was that he would shoot his brother without hesitation if he ever set eyes on him again. The bearer of the above message was apparently flogged into the bargain.'(103) A similar appeal to De Wet from the Bethlehem peace committee, also in January 1901, was equally fruitless and, according to A M Grundlingh, no further efforts were made to reach commandos in the field in this fashion, apart from the informal effort of two dominees, Charles Murray and J F Botha.(104) These two at least succeeded in meeting De Wet (and former President Steyn), only to be rebuffed with a very hardline attitude that included British recognition of the full independence of the republics - harking back to the content of the original Boer ultimatum to Britain in October 1899.(105)

(General Christiaan de Wet

(Source: KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Museum Service)

It was ironic that when peace was eventually signed at Vereeniging on 31 May 1902, several of the Boer generals justified the rationale of surrender on the same grounds that Piet de Wet and others had done nearly two years earlier. General Louis Borha was one:

'It has been said that we must fight to the bitter end, but no one tells us where that bitter end is. Is it there, where everybody lies in his grave or is banished?'(111)

It had also become apparent by early 1902 that continued armed resistance threatened the very future of the 'volk', making possible Alfred Milner's pre-war utopia: de-Afrikanerised crown colonies.(112) Botha's sentiments were echoed by generals Koos de la Rey, Schalk Burger and Jan Smuts. This sheds an interesting slant on Smuts's recollection of Piet de Wet and Marthinus Prinsloo: 'Both tried to surrender the forces under their command; the blundering Piet de Wet failed and sought consolation in the infamy and pay of a National Scout ...'(113)

Peace feelers in the Cape Colony

In January 1901, the Kroonstad peace committee had initiated an appeal to the inhabitants of the Cape Colony to add their weight to bringing an end to the war and to salvage something from the failure of peace initiatives directed at the commandos.(114) This effort would appear to have been compromised by the presence of Piet de Wet in the Boer 'peace process', with many Cape Afrikaners aghast that the brother of such a Boer 'hero and patriot' as Christiaan de Wet could be 'working against' the republics.(115) Pakenham described De Wet on this occasion as a prize exhibit of a tame guerilla'.(116) Despite every assistance from Lord Milner and the prime minister of the Cape Colony, Sir Gordon Sprigg, the mission was a fallure.(117) If the strategy of recruitment from the commandos was not a success, there were always the surrendered burghers in the internment camps. The methods used were a combination of a stick and carrot approach with, on the one hand, emphasis on the continued ruination of the country and, on the other hand, financial and material inducements such as rations and equipment. This was an especially useful tactic in the case of those landed burghers with more to lose.(118) In February 1901, Piet de Wet led a delegation from the Bloemfontein peace committee on a chaotic and unsuccessful mission to Cape Town to canvas support.(119) At the Greenpoint prisoner of war camp, their arrival only served to incite intimidation of suspected peace sympathisers.(120) In the wake of this abortive visit, a separate camp for 'the moderate minority' was established in March 1901.(121) Another abortive appeal for peace came from Sammy Marks, the prominent Jewish millionaire businessman.(122)

British-Boer burgher forces

When the most severe proclamation to date, that of 15 September 1901 - threatening, inter alia, Boer leaders with perpetual banishment - failed to elicit much response, some 'handsuppers' opted for a more drastic measure of their own - active service against their former compatriots.(123) Lord Roberts had been wary ofusing armed surrendered burghers in active operations. As early as January 1901, Free State General J H Olivier, the victor of Stormberg, languishing as a prisoner of war on Ceylon (Sri Lanka) had 'offered to maintain peace in his own district in the Orange River Colony with a picked commando'.(124) Kitchener and Milner had not, however, regarded this as feasible.

(Transvaal National Scouts on parade

(Source: Emanoel Lee, To the bitter end, p 171)

Interestingly, of the booty, half was paid monthly, with the remainder going into a fund to support the resumption of farming operations once the war ended.(127) This loot-pay was later supplemented by colonial volunteer pay of five shillings per day.(128) Each corps was accompanied by two British colonial officers, one to act as intermediary with British columns and the other as a quartermaster.(129) The scouting expertise provided by the joiner burghers definitely sharpened the combat effectiveness of British columns, and reliable joiner 'agents' were even successfully infiltrated into commandos themselves.(130)

During the course of 1901, the various burgher corps were drawn together in the (Transvaal) National Scouts and the Orange River Colony (ORC) Volunteers, and placed under British Army uniform and disciplinary codes.(131) They received pay of 2s 6d per diem and, in addition, kept fifty percent of captured cattle.(132) The ORC Volunteers were the brainchild of De Wet and Commandant S C Vilonel of Senekal, while the National Scouts were led by A P J Cronjé and J C Celliers.(133) The process appears to have languished for some time in gestation, only receiving attention again in early 1902.(134) Eventually two units of the ORC Volunteers were established: one under Vilonel (200-strong) and stationed at Winburg, and the other (248 men) operated under De Wet out of Heilbron.(135)

In contrast to the numerically larger National Scouts (with a strength of 1 359), the ORG Volunteers were not engaged in any military actions, their short war service from March 1902 onwards consisting of reconnaissance missions, nocturnal raiding and the escort of British columns.(136) However, as early as 11 July 1901, eleven joiners had assisted in a raid near Reitz where several members of the Free State government were captured, and President Steyn narrowly evaded capture.(137) It could have been anticipated that the differences and similarities in the response of Transvaal and Free State burghers would have had an influence on the evolving relationship between the burghers of the two republics, but Fransjohan Pretorius makes no mention of this in Life on Commando.(138) There is also mention in sources on the war of a 'Loot Corps' and the 'Intelligence Corps', as well as numerous bodies of scouts, such as Waldon's Scouts.(139) Although the scouts and Orange River Colony Volunteers were entitled to the British campaign medals for the Anglo-Boer War, only about 57 bothered to claim it.(140) They were certainly not eligible for the Boer campaign medal, the 'Dekoratie voor Trouwe Dienst', which was promulgated on 21 December 1920 and required proof of service against the British without surrendering, taking parole or signing an oath of allegiance prior to 31 May 1902.(141)

As for Piet de Wet himself, A M Grundlingh comments:

'Dit Wil voorkom asof Piet de Wet hom hoofsaaklik met

die werwing van lede en organisasie van die korps besig gehou

het. Hy was self nie baie aktief in die veld nie en so ver vasgestel

kon word, het hy gedurende die laaste fase van die oorlog slegs

eenkeer as gids vir die Britte opgetree.'(142) (It appears

that Piet de Wet was primarily occupied with recruiting members

and dealing with the organisation of the corps. He was not

very active in the field and, as far as can be ascertained, only

served as a guide for the British on one occasion during the

last phase of the war.) However, the Reverend J D Kestall

suggests that De Wet (one of the 'traitorous Afrikanders')

had played a more direct role in a large-scale British sweep

through the Lindley district in December 1901. Kestall was

appalled: 'How must every noble sentiment have been

stifled in these men!'(143) Kestall recorded a revealing

(alleged?) conversation between De Wet and a certain Mrs

van Niekerk, a former close acquaintance whose farmstead

was being destroyed:

The colonial press in Natal

The colonial press in Natal painted a glowing but somewhat condescending picture of the National Scouts. This is evident in a Natal Mercury report of 13 June 1902, when a parade of Scouts was reviewed by Lord Kitchener, that 'arch-enemy' of the Boer people. Among the high-ranking Boer leaders present were Andries Cronjé and John Dory, brother-in-law of General Schalk Burger. Kitchener told them that 'they had taken arms when the fanaticism of those still in the field thoroughly justified the Scouts' actions.'(152) This might be debatable, but his point that their services would not be forgotten was certainly true, but not for the reasons that the British would have preferred.

When the fighting was over, what did the 'joiners' get out of their actions?

According to The Times History of the War in South Africa, the British government was very aware of its obligation towards those Boers who had fought in its ranks against their own people. It was pointed out that among the most implacable of Britain's enemies in the Anglo-Boer War were the sons of those burghers who had fought on the British side in the war of l880-188l.'(153)

When the British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, visited South Africa in January 1903, he met with a delegation of 'wapenneerlêers' (those who had laid down arms) from the Transvaal and Orange River colonies.(154) Piet de Wet and Vilonel represented the Free Staters. High on their agenda were accusations against the British occupants that they were not receiving the compensation they had been promised. Many of the 'hendsoppers' were openly saying that they would have been better off holding out to the end and receiving the compensation accruing from the Treaty of Vereeniging.(155) Their lobbying of Chamberlain bore fruit. They benefited from two funds, one for a total of £3 million and a second special fund (the Protected Burgher Fund) of over £4 million. In addition, they were able to lodge claims with a £2 million fund intended mainly for British subjects, neutrals and blacks.(156) For much of this belated reward, the so-called 'ex-military burghers' owed much to the efforts of a Royal Engineer officer, Major E H M Leggett, who had served as a staff officer at the headquarters of both the National Scouts and the Orange River Colony Volunteers.(157)

Helen Bradford suggests that British promises to Boer civilians and 'hendsoppers' were largely nullified in practice.(158) After the war there was also a plea from certain 'afvallige burgers' (renegade burghers) that they be readmitted into Afrikaner society. Barely two weeks after the Treaty of Vereeniging, Piet de Wet addressed a futile letter to the press calling for a rapprochement between the two distinct groups that then existed.(159) In fact, in many districts of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony, including Piet de Wet's home district of Lindley, distinct schisms soon became apparent, especially in the realms of social interaction and education. The 'hendsoppers' were made to feel distinctly unwelcome.(150) However, while Christiaan de Wet was to take the enmity against his brother to the grave, others were more forgiving. Napier Devitt relates the case of one 'joiner', a leading Transvaal politician after the war, seeking and receiving the forgiveness of General Louis Botha.(161) By 1904 ex-'joiners' were still complaining that the British had not held up their end of the deal. At a meeting of National Scouts held at Standerton on 25 July that year, it was said that all they could realistically expect was 'an open grave in which their bodies might be thrown; their children would grow up to spit on those graves, and to curse them.'(152)

Several years later, in November 1907, Piet de Wet and S C Vilonel took part in the elections that followed the granting of self-government in the colony in June that year. De Wet and Vilonel stood unsuccessfully as independent candidates in Lindley and Senekal respectively.(163)

Anti-war opposition in Britain

Boer commanders like Piet de Wet may have been influenced by the anti-war (and sometimes, but not always, pro-Boer) opposition to the war in Britain. The anti-war movement had to keep a low profile during the emotive opening nine months ofthe war, especially during the crises of the sieges of Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking, and the defeats of Black Week in December 1899. However, after the occupation of Pretoria in June 1900, public opinion in Britain cooled and the anti-war movement emerged from its foxholes, especially when the controversial scorched-earth policy and the internment of Boer civilians created an opening for protest.(164) This was about the time of the capitulation of De Wet and other Boer leaders.

Some concluding thoughts

Piet de Wet has generally been condemned in Afrikanerdom, both by his own and subsequent generations, and by historians. However, it should be mentioned that he appears to have had genuinely at heart the mounting destruction and suffering of the republics.(165) It would not have been the first or last time in history, however, that a clearly defeated army fought on in a hopeless cause, almost regardless of the human and material cost. It is also possible that De Wet became a victim of the Afrikaner nationalist almost mythic eulogising of the Boer military heroes of the war - not least his brother.(166) Whether the 'joiners' had any decisive effect in terms of hastening the end of the war is debatable. On the one hand, the revulsion that their actions instilled in the burghers drove many to renewed efforts against the British, but their actions also had a demoralising effect.(167) The particular revulsion directed at 'joiners' who held high military and social positions, such as Piet de Wet, is probably also related to the significant moral guidance exercised by Boer officers on often impressionable burghers.(168)

'While commandos were counting their losses, their opponents were so growing in strength through the infusion of traitorous blood that the dread time might come when fighting partisans behind the republican cause could be outnumbered by "their own people" who had turned on it. If by no means a principal factor in bringing about Boer defeat, the plague of collaboration was there in the final losing equation between actual hardship and loss of faith.'(169) Piet de Wet had displayed rather ordinary military capability and his decision to surrender was also motivated by his lukewarm approach to the irregular warfare that was to become the only option for the Boers from mid-1900 onwards. 'Bittereinders' and 'handsuppers' continued to skirmish for many years after the war, and ultimately succeeded in largely burying their differences, but the joiners were beneath contempt and beyond redemption and perhaps beyond Christian forgiveness too'.(170) This contempt was reflected strongly in the works of Afrikaner nationalist writers after the war.(171)

Boer punishment of 'traitors', as illustrated in the

sensationalist French weekly Le Petit Parisien, 1901

(Source: F Pretorius The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902, p 67)

Piet de Wet also extended a conciliatory hand to his former British enemies, urging an acceptance of a benevolent British control.(174) However, it may have been that the British harboured a greater respect for their former Boer opponents, in much the same way as the burghers respected the British soldier's commitment to his task and orders. The 'joiners', on the other hand, had 'stabbed them in the back'.(175) Significantly, it was Botha, opposed to war at its outset but arguably its greatest military leader, who made reconciliation the hallmark of his political career.(176) Ironically enough, Christiaan de Wet was also to end up condemned as a traitor, albeit not in popular Afrikaner perception, when in 1914 he opposed South Africa's assistance to Britain in the First World War, when Union forces under his former compatriot, General Louis Botha, invaded German South West Africa.(177) Curiously, Christiaan de Wet prefaced his famous autobiography of his wartime adventures, Three Years War, with the greeting: 'To my fellow subjects of the British Empire'.(178)

This paper was written at the request of Adri Joubert,

a great-granddaughter of Piet de Wet.

Adri Joubert, August 1994

Finally, there is a curious reference in S B Spies's Methods of Barbarism? of 'bittereinder' allegations that Piet de Wet was the 'father' of the concentration camp policy.(182) Spies comments on the assumption in the Times History of the War in South Africa, as well as more recent works, that surrendered burghers advocated the system as a penalty for burghers still on commando, but he says that there is no evidence of a direct role.(18)3 The reason for the accusation is probably that the British used the 'explanation' that camps were intended, inter alia, for the protection of 'hendsoppers and 'joiners' and their families from the commandos, as a reason to term them 'refugee camps', although this category of internee was always a small minority.(184) These families reputedly also enjoyed various privileges in the camps, especially in terms of rations.(185)

References

1. P Marais, Die vrou in die Anglo-Boereoorlog, p l97.

2. CJ Barnard, 'Studies in the generalship of the Boer commanders', p 151.

3 Bill Nasson, The South African War 1899-1902, p 214.

4. Nasson, The South African War 1899-1902, p 214.

5. K du Pisani and L Grundlingh, 'Volkshelde: Afrikaner nationalist

mobilisation and representation of the Boer warrior', p 18;

J Malan, Die Boere Offisiere 1899-1902, p 28.

6. Emanoel Lee, To the bitter end, p 172.

7. A M Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 240-1.

8. Grundlingls, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 240.

9. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 241;

Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II, p 193.

10. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 241.

11. Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II, p 193.

12. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 241.

13. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 241-2.

14. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 242.

15 Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 242.

16. J H Breytenbach, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, IV, pp 10, 16, 29.

17 Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 242;

Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II, p 193.

18. Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War, pp 390-3; Breytenbach, Die geskiedenis van die

Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, V, pp 192-205; and see Lee, To the bitter end, pp 113-4 for Sannaspost.

19. Breytenbach, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, V, pp 222-3, 224-5.

20. Breytenbach, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheiddoorlog, V, pp 262-5, 301-3, 305-312.

21. Breytenbach, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, V, p 458.

22. A Conan Doyle, The great Boer War, p 433.

23. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 242-3.

24. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 424.

25. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 424.

26. Winston Churchill, 'Ian Hamilton's March' in Frontiers and Wars, p 524.

27. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 424.

28. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 243.

29. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 243.

30. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 436.

31. Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II, p 193.

32. Grundlingh. Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 243.

33. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 244.

34. P J Delport, 'Die rol van Generaal Marthinus Prinsloo gedurende

die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog', p 113.

35, Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', pp 185-7.

36. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', pp 188-90.

37. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', p 191.

38. Delport. 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', pp 191-2.

39. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', pp 192-3.

40. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', p 196.

41. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', p 197.

42. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', pp 201-3.

43. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', p 203.

44. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinslno', pp 208-9.

45. Delport, 'Die rol van Genl Marthinus Prinsloo', p 215.

46. P J du Toit, Diary of a National Scout, pp 1-5.

47. Barnard, 'Studies in the generalship of the Boer commanders', p 151.

48. Barnard, 'Studies in the generalship of the Boer commanders', pp 151-3.

49. Barnard, 'Studies in the generalship of the Boer commanders', pp 154, 156.

50. Philip Bateman, Generals of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 112-3.

51. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 245-6.

52. Grundlingh. Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 244.

53. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p245; V B Solomon,

'The hands-uppers' in Military History Journal, Vol 3, no 1, June 1974, p 13;

F Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902, p 67.

54. Breytenbach, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, V, pp 505-8.

55. Helen Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers: Afrikaner nationalism,

gender and colonial warfare in the South African War', UNISA Library Conference, 1998, p 3.

56. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 4.

57. S B Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 55.

58. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 55 and see pp 55-7 for details of

British administration of the Orange River Colony, as the Free State was named after annexation.

59. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', pp 5-6.

60. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 7.

61. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 8.

62. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 13; Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, pp 28-9, 34-7, 40-1.

63. Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War, p 68.

64. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 14.

65. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 8; Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, pp 188-9.

66. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', pp 9-10.

67. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 8.

68. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 9.

69. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 13.

70. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 170.

71. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', pp 11-12.

72. R W Schikkerling, Commando Courageous, p 41.

73. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 13.

74, Churchill, 'Ian Hamilton's March' in Frontiers and Wars, p 527;

Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 173.

75. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 246;

Eric Rosenthal, General de Wet, p 82; Christiaan de Wet, Three Years War, p 154.

76. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 247.

77. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 247.

78. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 244.

79. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 244; Rosenthal, General de Wet, pp 834.

80. De Wet, Three Years War, p 170.

81. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 244-5.

82. Churchill, 'Ian Hamilton's March' in Frontiers and Wars, p 524;

Pakenham, The Boer War, p 424.

83. Lee, To the bitter end, p 171.

84. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 203.

85. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 90; Solomon, 'The

hands-uppers', pp 16-17; Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War, p 71;

Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, pp 202-5.

86. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 90.

87. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 90.

88. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 202.

89. Nasson, The South African War, p 215.

90. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 90-1.

91. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 108.

92. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 16.

93. C J Scheepers, Spieëlbeeld Oorlog 1899-1902, p 100.

94. Scheepers, Spieëlbeeld Oorlog 1899-1902, p 102.

95. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 15; Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, pp 46-8.

96. Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War, p 72.

97. Fransjohan Pretorius, Life on Commando, p 212, and see p 216.

98. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 248.

99. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 248.

100. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 107; Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 205.

101. Tabitha Jackson, The Boer War, p 140. See Lee, To the bitter end, pp 122-5,

for the full text of this letter.

102. Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II, p 193.

103. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 107, 111; Jackson, The Boer War, p 140.

104. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 107-8.

105. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 109.

106. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 114.

107. Lee, To the bitter end, p 125.

108. Churchill, 'Ian Hamilton's March' in Frontiers and Wars, p 484.

109. Churchill, 'Ian Hamilton's March' in Frontiers and Wars, p 484.

110. Jan Ploeger, 'Burgers in Britse Diens 1902' in Militaria, 15/1, 1985, p 19.

111. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 19.

112. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 568.

113. Gail Nattrass and S B Spies (eds), Jan Smuts: Memoirs of The Boer War, p71;

and see Pretorius, Life on Commando, chapter 11, for the saga of the Boer bittereinder.

114. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 109; Solomon,

'The hands-uppers', p 16; Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, pp 205-6.

115. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 109.

116. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 488.

117. Spies, Methods of Barbarism? p 206.

118. Nasson, The South African War, p 215-16.

119. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 110.

120. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 114; Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 206.

121. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 114-15.

122. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 488.

123. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 17; The South African Mounted Irregular Forces, p 36.

124. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 201.

125. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 202.

126. Nasson, The South African War, p 214.

127. The Natal Witness and The Natal Mercury, 25 November 1901.

128. Lee, To the bitter end, p171.

129. The Natal Mercury, 25 November 1901; Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 208.

130. Nasson, The South African War, pp 214-15; Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War, p 72.

131. Nasson, The South African War, p 215; Peter Boyden et al. (eds),

Ashes and Blood: The British Army in South Africa, 1795-1914, p 81.

132. The Natal Mercury, 25 November 1901; Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 250;

The South African Mounted Irregular Forces, p 56.

133. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 240, 251.

134. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 208.

135. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers enJoiners, pp 208-9, 216.

136. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 216-17.

137. Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War, p 72.

138. Pretorius, Life on Commando, pp 241-3.

139. The South African Mounted Irregular Forces, p 52.

140. The South African Mounted Irregular Forces, p 58.

141. D R Forsyth, The Medal Roll, pp 9-11.

142. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 216.

143. J D Kestall, Through Shot and Flame, p 224.

144. Kestall, Through Shot and Flame, pp 224-5.

145. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 216-17.

146. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 216-17.

147. Scheepers, Spieëlbeeld Oorlog, pp 102-3.

148. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 217.

149. Wessels (War Museum of the Boer Republics) to writer, 1 April 1996.

150. Napier Devitt, The concentration camps in South Africa during the

Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, p 24.

151. Schikkerling, Commando Courageous, p 234.

152. The Natal Mercury, 13 June 1902.

153. L S Amery (ed), The Times History of the War in South

Africa, 1899-1902, Volume VI, p 53.

154. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 296.

155. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 296;

Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 17; Ploeger, 'Burgers in Britse Diens, pp 19-21;

Rosenthal, General de Wet, p 171; Amery, The Times History, Volume VI, pp 43, 152.

156. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 297, 302.

157. Amery, The Times History, Volume VI, pp 53-4.

158. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 4.

159. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 310-11.

160. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, pp 311-12;

Amery, The Times History, Volume VI, pp 52-3.

161. Devitt, The concentration camps in South Africa, p 24.

162. The Natal Witness, 26 July 1904.

163. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 350.

164. David Smurthwaite, The Boer War, 1899-1902, pp 158-9.

165. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 245.

166. Bradford, 'Gentlemen and Boers', p 2.

167. Pretorius, The Anglo-Boer War, p 73.

168. Pretorius, Life on Commando, p 333.

169. Nasson, The South African War, p 216.

170. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 19.

171. Du Pisani and Grundlingh, 'Volkshelde', pp 5-6.

172. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 13.

173. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 15.

174. Grundlingh, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners, p 249.

175. Jackson, The Boer War, p 141.

176. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 21.

177. Bateman, Generals of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 114-15.

178. De Wet, Three Years War, preface.

179. Nasson, The South African War, pp 216-17.

180. Nasson, The South African War, p 217.

181. Du Pisani and Grundlingh, 'Volkshelde', pp 11-17/

182. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 183.

183. Spies, Methods of Barbarism?, p 184.

184. Marais, Die vrou in die Anglo-Boereoorlog, p 195.

185. Marais, Die vrou in die Anglo-Boereoorlog, p 195.

186. Solomon, 'The hands-uppers', p 13.

Bibliography

Amery, L S (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902, Volume VI,

(London, Sampson Low, Marston and Co, 1902-1905).

Barnard, C J, 'Studies in the generalship of the Boer commanders', in Military History Journal,

Volume 2, No 5, June 1973.

Bateman, Philip, Generals of the Anglo-Boer War, (Cape Town, Purnell, 1977).

Bizley, H C, 'Anglo-Boer War Diary', Natal Carbineers History Centre.

Boyden, Peter B, Alan J Guy and Marion Harding (eds), Ashes and Blood: The British Army in South Africa,

1795-1914, (London, National Army Museum, 1999).

Bradford, Helen, 'Gentlemen and Boers: Afrikaner nationalism, gender and colonial warfare in the South

African War', in 1899-1902: Rethinking the South African War, UNISA Library Conference, 1998.

Breytenbach, J H, Die Geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog in Suid-Afrika, 1899-1902, volumes IV

and V, (Pretoria, Die Staatsdrukker, 1977 and 1983).

Cameron, Trewilla and S B Spies, A new illustrated history of South Africa, (Southern Book

Publishers/Human & Rousseau, 1991).

Churchill, Winston S, Frontiers and Wars, (London, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1962).

Conan Doyle, A, The Great Boer War, (London, Smith, Elder & Co, 1900).

Delport, P J, 'Die rol van Generaal Marthinus Priosloo gedurende die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog', MA, University

of the Orange Free State, 1972.

Devitt, Napier, The Concentration Camps in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902,

(Pietermaritzburg, Shuter & Shooter, 1941).

De Wet, Christiaan Rudolf, Three Years War, (Westminster, Archibald Constable & Co, 1902).

Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II, HSRC.

Du Pisani, Kobus and Louis Grundlingh, 'Volkshelde:

Afrikaner nationalist mobilisation and representation of

The Boer Warrior', 1899-1902: Rethinking the South

African War, UNISA Library Conference, 1998.

Du Toit, P J, Diary of a National Scout, (HSRC, 1974).

Forsyth, D R, The Medal Roll, Johannesburg, 1976).

Grundlingh, AM, Die Hendsoppers en Joiners: Die rasionaal

en verskynsel van verraad, (HAUM, 1979).

Jackson, Tabitha, The Boer War, (London, Channel 4 Books, 1999).

Kestall, J D, Through Shot and Flame, (Africana Reprint

Society, Johannesburg, Africana Book Society, 1976).

Lee, Emanoel, To the bitter end: A photographic history of the

Boer War 1899-1902, (Viking, 1985).

Malan, Jacques, Die Boere Offisiere 1899-1902, (Pretoria, J P van der Walt, 1990).

Marais, Pets, Die vrou in die Anglo-Boereoorlog 1899-1902, (Pretoria, J P van der Walt, 1999).

Nasson, Bill, The South African War 1899-1902, (London, Arnold, 1999).

Natal Mercury, The, 25 November 1901, 13 June 1902.

Natal Witness, The, 25 November 1901, 26 July 1904.

Nattrass, Gail and S B Spies (eds), Jan Smuts: Memoirs of The Boer War,

(Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1994).

Pakenham, Thomas, The Boer War, (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1979).

Pakenham, Thomas, The scramble for Africa, (Johannesburg, Jonathan Ball, 1991).

Pama, C, Die groot Afrikaanse familienaamboek, (Human & Rousseau, 1983).

Ploeger, Colonel (Dr) Jan, 'Burgers in Britse diens (1902)', in Militaria, 15/1,1985.

Pretorius, F, The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902, (Cape Town, Don Nelson, 1985).

Pretorius, Fransjohan, Life on commando during the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902, (Human & Rousseau, 1999).

Rosenthal, Eric, General de Wet, (Cape Town, Simonelium Publishers, 1968).

Scheepers, Dr C J (comp), Spieëlbeeld Oorlog 1899-1902, (Tafelberg, Die Afrikaner en sy Kultuur, 1974).

Schikkerling, RW, Commando courageous, (Johannesburg, Hugh Keartland, 1964).

Smurthwaite, David, The Boer War 1899-1902, (London, Hamlyn, 1999).

Solomon, V E, 'The hands-uppers', in Military History Journal, Volume 3, No 1, June 1974.

Spies, S B, Methods of Barbarism?, (Human & Rousseau, 1977).

The South African mounted irregular forces 1899-1902; A multinational force in The Boer War,

(Roberts [Medal] Publications, Ltd, nd).

Uys, Ian, South African Military Who's Who, (Germiston, Fortress Publishers, 1992).

Van Schoor, M C B, Die stryd tussen Boer en Brit: Die herinneringe van die boere-generaal C R de Wet,

(Cape Town, Tafelberg, 1999).

War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein.

Wassermann, Johan, The Eshowe Concentration and Surrendered Burghers Camp during the Anglo-Boer War

1899-1902, (Durban, Waterman Publishers, 1999).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org