The South African

The South African

by D W Aitken

Dudley Aitken is a curator at the South African National Museum of Military History.

On 1 October 1900, the Republican forces of the former Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR), large areas of which were then under British control, derailed a train travelling to Pretoria at Pan Station. On board the train were three hundred British troops, of whom 23 were killed by the attackers who opened a terrific fire upon the wreckage of the train.(1) This attack was followed on 6 October by an attack at Balmoral Station, where an engine was blown up and five trucks detailed. The follwing day a culvert was destroyed at Brugspruit, east of Balmoral Station and, on 9 October there was a serious accident at Kaapmuiden, probably caused by ZAR forces tampering with the line. On this occasion the train left the rails at the deviation crossing the Kaap River, killing three British troops and forty horses.(2)

On 1 November 1900, British troops under General Smith-Dorrien attacked the enemy camp at Van Wyk's Vlei in an effort to stop the train wrecking. It appeared that much of the interference with the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway had been traced to a laager at Witkloof, 30 km south of Belfast, and two columns of British troops set off as soon as it was dark to raid the enemy camp. A skirmish took place near Van Wyk's Vlei and the British withdrew to Belfast, but on 2 November the British engaged the ZAR forces in fierce fighting along the Komati River.(3) As the Boer forces continued to attack the railway during November 1900, the British threatened to retaliate by burning and razing those farms which were being used to launch the attacks. Thus, on 13 November, the British blew up the flour mill and burned down a number of houses at Witpoort and, on 16 November, did the same at Dullstroom.(4)

An armoured train, wrecked by Boer forces near

Vlakfontein, Transvaal, 8 October 1900

(Source: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol III, p 203)

The next big attack on the railway line by the ZAR

forces took place on 7 January 1901. The places selected

for attack were Machadodorp, Dalmanutba, Belfast,

Wonderfontein and Pan, all railway stations on the

Pretoria-Delagna Bay line, General Ben Vilinen was to

attack from the north and commandants Botha and Smuts

from the south. General Ben Viljoen describes the part he

played in the attack on 7 January 1901:

'It was one of those nights known in the Steenkamp

Mountains as "dirty nights", very dark with a piercing

easterly wind. About 9 o'clock the mist changed into heavy

rain. Exactly at midnight all had arrived at the place of

destination. The positions near Monument Hill (Belfast)

and the coal mine were attacked simultaneously. There were

four forts near the Monument which the burghers stormed

in the dark and captured, but suffered fairly heavy

casualties. Twenty minutes of very fierce hand-to-hand

fighting took place while the forts were being overrun by

the ZAR forces and 21 prisoners of war, a Maxim and 20

boxes of ammunition and provisions were taken form the

four captured forts.' Ben Viljoen's men then advanced into

Belfast but failed to make contact with the other ZAR forces

and decided to withdraw as dawn approached. The attacks

on Wonderfontein, Pan, Dalmanutha and Machadodorp

Stations all failed on 7 January and the Republican forces

lost 40 killed and wounded.(6)

During January 1901, the ZAR forces between Carolina and Middelburg were estimated at between 5 000 and 7 000 men under Botha and Viljoen and the position of the British garrisons along the railway line was a critical one. At every moment, they were liable to attack by greatly superior forces and the perpetual vigilance necessary to prevent the success of such attacks imposed a severe strain upon officers and men, the more so as the rations for the men were by no means adequate, owing to the difficulty of maintaining communications. Telegrams reaching England from Delagna Bay seemed to indicate that for some time previous to the attacks upon the posts along the railway in January, the line at some point between the Portuguese frontier and Belfast had passed completely into the possession of the ZAR forces. A message reported that from 7 January the British had been holding the line and added that military supplies were being forwarded in great quantities, despite a shortage of engines and the interruption of traffic by frequent derailments.(7)

The derailment of trains along the Pretoria - Delagoa Bay line continued throughout January 1901. Hardly a day passed without a train being wrecked or blown up or the line damaged at some point. On the morning of 17 January 1901, the engine of the westward-bound train was blown up and the train derailed near Brugspruit. This was the work of the notorious train-wrecker among General Ben Viljoen's forces, Captain Jack Hindon, who became an expert in destroying trains and had manufactured a special mine for that very purpose. This mine was made in the following manner: A Martini-Henry rifle was used and sawn off four inches before and behind the magazine, and then the trigger guard was flied so that the trigger was left exposed.(8) The two men who took the specially prepared rifle and bucket of dynamite to the spot chosen for the mine were very carefil not to leave any footprints that could be traced by the British patrols. To avoid leaving any footmarks, they walked for a considerable distance on the rails. The stones were carefully removed from underneath the rails and then carefully replaced to fill up the hole after the instruments of destruction had been adjusted. The trigger was placed in contact with the dynamite and just enough above the ground to be affected by the weight of the locomotive, but so little exposed as to be passed unnoticed. All surplus stones were then taken away in a bag and great care was taken to conceal all traces of the mine.(9)

Boers attack a blockhouse on the railway near Brandfort 8 August 1901.

(Source: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol II, p 801)

In defence of a derailed train, British troops fight back,

Delagoa Bay Railway line between Alkmaar and Godwaan, 20 May 1901.

(Source: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol II, p 619)

The next big train attack took place six days later on 23 January as Lord Kitchener was travelling from Pretoria to Middelburg to meet General Smith-Dorrien. As his train approached Balmoral Station, signs that the enemy were in the vicinity were observed and it was felt that special precautions should be taken to protect the train. A pilot engine was sent ahead along the suspect part of the line but it returned safely and reported that nothing was amiss. However, Lord Kitchener was still not convinced and issued orders that two heavily-laden trucks be prefixed to the pilot engine and that the engine with its trucks was to precede his train. His order was obeyed and his own train followed slowly. The combined weight of the trucks and the engine was sufficient to release the trigger of the mine that had been planted on the track and the trucks were blown into the air and the pilot engine derailed. The train wreckers came out of hiding to admire their work, but this time their victims had escaped and they saw Lord Kitchener's train quickly backing down the line to safety. British reinforcements were rapidly summoned and after a short skirmish during which the ZAR forces succeeded in capturing a number of prisoners, the train wreckers withdrew to safety to wait for another chance to attack the railway.(12)

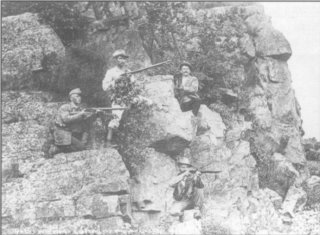

Boer forces at the side of a railway near Pretoria

(Photo: by courtesy, SANMMH)

A typical Boer commando group

(Photo: by courtesy, SANMMH)

From 3 to 14 February 1901, the British forces swept through the area south of the Delagoa Bay Railway, each day laying waste acres and acres of crops and slaying thousands of sheep while over 500 trucks were used on the railway to carry supplies forward to the British troops. By 14 February they had reached Amsterdam, near the Swaziland border.(14)

As the British began to pay more attention to the defence of the Delagoa Bay line, Captain Hindon and the other train wreckers were forced to adopt new methods of attack. During the day, increasing numbers of armoured trains were brought into use and Hindon's men began to lay their mines during the night and watch the result of their efforts from a safe distance during the day. Knowing that, as a rule, the British soldier was not adept at following spoor, it puzzled Hindon that so many of his mines laid at night were being discovered and harmlessly disposed of by the British. It seemed as if the British could follow his tracks in the veld over distances of some 600 yards (548 metres) while making an early morning reconnaissance, Hindon learned what was happening: The British were simply following obvious marks left in the dew. To solve the problem, Hindon made sure that his mines were laid as early as possible in the evening before the air cooled and dew formed on the grass and from that time onwards the British again had very little success in tracing his tracks.(15)

To guard against attacks, it became the custom for the British to send an armoured train, with the engine between a few reinforced trucks, in front of each train. In this way, if the line was sabotaged, the truck in front, usually carrying a few soldiers, would be blown up by the mine, while the engine would remain intact and could then be uncoupled from the damaged truck and returned safely with the trucks still on the rails.(16) However, Captain Hindon and his vigilant Lieutenant Slegtkamp soon got wise to this scheme and would first let the armoured train with its load of British soldiers pass before they activated the mine to explode under the engine of the train which was following, a method which worked well while there were very few blockhouses on the Delagoa Bay line.(17)

On 9 February 1901, Captain Hindon received a letter from the State Secretary, F W Reitz, requesting him to remove certain parts of the first engine he captured. These parts were needed by General Beyers for the only old engine he had for his use on the line between Warmbaths and Pietersburg.(18) Hindon's opportunity came on 13 February 1901, while he was hiding with about 200 men in a plantation near the railway line east of Balmoral. Lieutenant Slegtkamp laid the mine and waited for a signal from Captain Hindon who was watching to see when the second train would leave Balmoral. The armoured train passed safely by and within three minutes of the next train leaving Balmoral, Slegtkamp had his mine set and was safely back in his hiding place, one hundred metres from the line.

The heavily laden goods train steamed by and the mine exploded under it.(19) The Republicans charged out of the plantation towards the wrecked train while the British soldiers took cover in the water furrows on both sides of the railway line. From Hindon's vantage point on the top of the hill, from where he had given the signal to Slegtkamp, he was able to sum up the situation very well. With a group of his men, he rode to the right of the main group, where they poured in a devastating flank fire upon the soldiers in the water furrows, forcing them to surrender.(20)

Trolleys appeared from the plantation and were quickly loaded with clothing, tobacco, salt, bread and other articles while Hindon and Field-Cornet Jan Viljoen drove a group of soldiers back that were trying to advance from Brugspruit. The ZAR forces came under cannon fire from the fort at Brugspruit but the raid was over and the attackers disappeared over the hills with their booty.(21)

During the rest of February 1901, Hindon and Slegtkamp made various attempts to capture trains in the vicinity of Uitkyk Station. During one of these attempts, a train trolley, carrying a ganger and a few blacks, was blown sky-high. Shortly before this event, a patrol officer had stood within ten yards of Hindon and had looked through his binoculars and come to the conclusion that there were no enemy forces in the vicinity!(22) Towards the end of the month, while travelling by train from Pretoria to Middelburg, Lord Kitchener himself was extremely fortunate to avoid capture by Hindon and his commando. However, for the first time in Hindon's experience, the mine failed to explode. The train ran safely over the mine and Hindon's men were so amazed that they did not fire a single shot at it.(23)

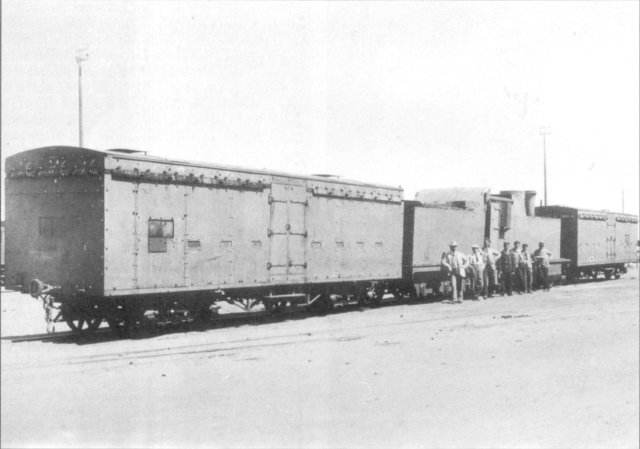

An armoured train, used by the British forces during the Anglo-Boer War

(Photo: by courtesy, SA National Museum of Military History)

On 11 March 1901, Captain Hindon struck again between Wilge River and Balmoral stations. As soon as the mine exploded under the engine, the British troops on the train took cover in the water furrows alongside the track, where the high banks offered good protection, and a twenty minute exchange of fire took place at a distance of 400 metres before Hindon realised that his men would never succeed in reaching the train unless they were willing to make a desperate charge under fire. Hindon called for volunteers and ten came forward out of his hundred or so men and with these he stormed the train. Meanwhile, Field-Cornet Piet Minnaar and ten men fired on the blockhouse from a distance of fifty metres and Erasmus with a group of men opposed British troops coming from Balmoral Station. With the loss of one of his men, shot dead from the blockhouse, Hindon succeeded in reaching the water furrows and forcing not less than 35 soldiers and about 30 blacks to surrender. The rest of his men immediately began offloading clothing, blankets, foodstuffs and saddles from the train. Observing that British troops were charging from the blockhouse, while others were approaching from Balmoral Station, Hindon saw it was time to make his getaway. He set the train alight and made good his escape.(27) This was the first and the last time that Hindon attacked a train within sight of a blockhouse because it was obvious to him that, to have a reasonable chance of success, he must have a cannon at his disposal and the only one he could obtain was in Pietersburg.(28) The task of attacking the railway was clearly becoming more onerous as increasing numbers of blockhouses were being built all along the railway.

General Ben Viljoen's men were also very active in March 1901 between Belfast and Wonderfontein on the Delagoa Bay Railway. These stations were situated only 10 km apart, with a garrison at each station with two or three guns and two armoured trains held in readiness to proceed to any place within their area when anything irregular occurred on the line. Between the two stations, the railway was also guarded by blockhouses by March 1901. No trains ran at night and every morning the line was carefully inspected.(29)

During March 1901 Ben Viljoen and his men were encamped at Steenkampsbergen and about 100 men were detailed to attempt to capture a train. A mine was laid and the men took up their positions behind a small hill about two kilometres from the railway. The first train expected in the morning was the mail train and the men were told to capture as much food and clothing as possible as well as newspapers. The early morning scouts failed to discover the mine.(30)

Viljoen posted two men at the top of a hill and from their vantage point they had a clear view of the railway line. The morning passed with no train appearing and by 14.00 the men and horses were complaining of hunger. Eventually, at 16.00, smoke was seen and then a train appeared. With a tremendous shock the mine exploded, overturning the engine and bringing the train to a sudden halt. Viljoen's men spread out and stormed the train. When they were about 200 metres from the train, the British troops opened fire but they shot badly and at random. At 100 metres, Viljoen's men dismounted and after a very short exchange of fire, the British showed the white flag and about twenty soldiers surrendered. Eight sacks of European mail were seized and the part of the train not occupied by women and children being transported to the Concentration Camps, was destroyed.(31)

In a similar attack, Viljoen's men seized a train near Pan Station which was carrying presents for the British soldiers and a miscellaneous assortment of cakes, puddings and other delicacies.(32)

Towards the end of March, Viljoen's men attacked a train near Wonderfontein Station, but unfortunately for them, this was an armoured train and, as they charged the train over open ground, they were exposed to the heavy fire from guns on the trucks as well as the fire of a hundred British riflemen. They failed to take the train by storm and, having lost three men killed, were forced to retire.(33)

As more and more blockhouses were built along the railway, attacks on the line became steadily more difficult to carry out and from March 1901 the number of successful attacks dwindled considerably.

Captain Hindon's men again attacked a supply train near Godwan Station on 20 May 1901. This train had two engines with several trucks in between them and in front of them in order that both engines would not be disabled in the event of a mine exploding. Hindon, on this occasion, used an observation mine which was detonated by a wire carried to a distance of 40 metres from the track. The mine exploded and the ZAR forces charged the train and began looting. However, some British troops in an armoured truck hindered them by keeping up a steady fire and when an armoured train arrived they were forced to retreat with only a small amount of booty.(34)

Boers force a crossing over the railway line by driving their

cattle and horses over barbed wire and other obstacles, 7 February 1902.

(Source: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol III, p 913)

As Hindon's men were on their way to lay a mine on the track, they were surprised by two cannon shots from the direction of Balmoral. Later, they met up with Viljoen's men who were attacking a blockhouse in preparation for their dash across the line. At an awkward moment for Viljoen's commando, an armoured train appeared on the scene, lighting up the whole area with its searchlights and attacking the ZAR forces with field guns and Maxims. A number of Viljoen's men succeeded in crossing the line with a loss of ten dead and wounded. Viljoen, with about 100 men, two guns and the wagons, was forced to remain on the other side of the line.(36)

Determined to rejoin his men, Viljoen asked Lieutenant Slegtkamp to lay mines on the line between Uitkyk and Middelburg stations and between Uitkyk and Great Olifants River. Viljoen planned to cross at a drift near Olifants River while Captain Hindon prevented an attack from Middelburg. Commandant Groenewald and Field Cornet Pienaar were to lead the crossing over the railway on a smooth gravel road about 2 000 metres from Uitkyk Station.(37) Captain Hindon surveyed the area of operations from a high hill near Harteheestfontein and noticed that the British had built a blockhouse at the very spot where they were planning to cross over the line that night! He immediately altered the crossing point to an old road about 1 000 metres to the east.(38)

On 27 June 1901, between 20.00 and 21.00, the ZAR forces made their attempt to cross the railway at the point Captain Hindon had chosen the day before. While the crossing was in progress, however, British troops, hiding in the darkness nearby, opened fire. The two guns were safely taken across, but soldiers began shooting from the nearby blockhouse and sending off rockets to summon the armoured trains. The ammunition wagon stuck fast in one of the furrows alongside the track but, with the efforts of about twenty men, it was freed and safely moved across. Next came the ox wagons and carts, all (with one exception) of which succeeded in crossing. Only General Vujoen's own wagon, which had suffered a broken disselboom in the attempt, had to be abandoned. The oxen, however, were cut loose and saved. Not a single man and only one wagon had been lost in the crossing over the line.(39)

Further success was achieved by the train wreckers that same night. Lieutenant Slegtkamp had just finished laying his last mine between Middelburg and Uitkyk stations when an armoured train came steaming out of Middelburg at full speed, intent on coming to the aid of the blockhouse that had sent up rockets asking for assistance. The mine exploded under the engine and the entire train was still lying at the fatal spot the following morning.(40)

The events of 26 and 27 June are described by the

British as follows:

'On the night of June 26th the OC at Brugspruit was

alarmed by rockets going up to the west, and by the noise

of firing. At once the armoured train got under way and

proceeded through the inky darkness to the scene of action.

The train carried two searchlights, a long 12-pounder and

two maxims. Nearing the last blockhouse but one

garrisoned from Brugspruit, it was found to be hotly

engaged. The rays of the searchlights showed some

hundreds of mounted Boers galloping away from the line.

The maxims were turned on them, and they disappeared.

After replenishing the ammunition supply of the engaged

blockhouse, the train ran on to the next one, which was

observed to be silent. The enemy were ahead in swarms, and

they were given the full fire of the train at close quarters

Unfortunately, the leading maxim jammed at the fourth

round, but the rifles of the men were plied with effect. The

Boers speedily disappeared over the veld, leaving behind a

cart and a number of horses. The train stopped to

investigate what had happened to the men in the silent and

empty blockhouse, taking the precaution to call up Captain

Nanton, the chief of the armoured train service on the line,

and the forces at Balmoral and Middelburg. Presently, out

of the darkness came shouts, and three of the garrison of the

captured blockhouse appeared on the scene. They stated

that another four were wounded at a farm close by. It

seemed that the Boers had opened the attack by driving a

wagon on the line, whereupon four of the men had come

out of the blockhouse to seize it. The moment they

emerged, a body of Boers in ambush opened fire on the

little party and shot three of them. With the garrison thus

weakened, they were able to rush the blockhouse, wounding

another man. The next post in the chain however, had

already given the alarm and the armoured train was on the

scene before the enemy could decamp. They lost in this

affair 40 horses and mules, 1 wagon, 35 cattle and a

prisoner, besides 6 dead who were found on the field by the

British. They are believed to have had 25 more men put

out of action by one of the 12-pounder shells from the

armouted train which had landed amongst a large group of

burghers. Their total strength was placed, by the prisoner,

at 600 men under Viljoen with two "pom-poms" - the

weapons captured from the Australians at Wilmansrust -

though they made no use of these guns. Not many

succeeded in getting to the north of the line, but a day or

two later they made another and a more successful attempt

to cross. Documents of the greatest military importance

were found in the captured cart, referring to the operations

which General Botha was contemplating near the Delagoa

Bay line.'(41)

By successfully crossing the Delagoa Bay Railway Line on 27 June, the ZAR forces under the command of Ben Viljoen managed to elude the British cordon of about 25 000 men under the supreme command of General Sir Bindon Blood and Viljoen's men were able to escape to the Bethal and Ermelo districts.(42)

Ben Viljoen's description of the events of 26 and 27

June 1901 is as follows:

'We approached the line between Balmoral and

Brugspruit, coming as close to it as possible with regard to

safety, and we stopped in a "dunk" (hollow place) intending

to remain there until dusk before attempting to cross The

blockhouses were only 1 000 yards (914 metres) distant

from each other, and in order to take our wagons across

there was but one thing to be done, namely, to storm two

blockhouses, overpower their garrison, and take our convoy

across between these two. Fortunately there were no

obstacles here in the shape of embankments or excavations,

the line being level with the veld. We moved on in the

evening (27 June), the moon shining brightly, which was

very unfortunate for us, as the enemy would see us and hear

us long before we came within range. I had arranged that

Commandant Groenewald was to storm the blockhouse on

the right, and Commandant W Viljoen that to the left, each

with 75 men. We halted about 1 000 paces from the line.

When 150 yards (137 metres) from the blockhouses the

garrison opened fire on our men, and a hail of Lee Metford

bullets spread over a distance of about 4 miles (6,4 km) -

the British soldiers firing from within the blockhouses and

from behind the mounds of earth. The blockhouse attacked

by Commandant Viljoen offered the most determined

resistance for about 20 minutes, but our men thrust their

rifles through the loopholes of the blockhouses and fired

within.'(43)

The first blockhouse surrendered with the loss of one of

Viljoen's men but the second blockhouse was built of stone

and offered much greater resistance. Viljoen continues with

his account:

'Many of our men had fallen and an armoured train

with a searchlight was approaching from Brugspruit. On

the other side of the blockhouse we found a ditch about

3 feet deep and 2 feet wide. Hastily filling this up, we let

the carts go over. As the fifth one had got across and the

sixth one was standing on the lines, the armoured train

came dashing at full speed in our midst. We had no

dynamite to blow up the line, and although we fired on the

train, it steamed right up to where we were crossing,

smashing a team of mules and splitting us up into two

sections. Turning the searchlight on us, the enemy opened

fire on us with rifles, maxims and guns, firing grapeshot.

Commandant Groenewald had to retire along the

unconquered blockhouse, and managed somehow to get

through. The majority of the burghers had already crossed

and fled, whilst the remainder hurried back with a pom-pom

and the other carts. I did not expect that the train

would come so close to us and was seated on my horse close

to the surrendered blockhouse when it pulled up abruptly

not four paces from me. The searchlight made the

surroundings as light as day and revealed the strange

spectacle of the burghers, on foot and on horseback, fleeing

in all directions and accompanied by cattle and wagons,

whilst many dead lay on the veld. However, we saved

everything with the exception of a wagon and two carts, one

of which unfortunately was my own... My two

commandants were now south of the line with half the

men, whilst I was north of it, with the other half. We

buried the dead next morning and that evening I sent a

message to the remainder of the commandos telling them to

cross the line at Uitkyk Station, south-west of Middelburg,

whilst Captain Hindon was to lay a mine under the line

near the station to blow up any armoured train coming

down. Here we managed to get the rest of our laager over

without much trouble. The "Tommies" fired furiously

from the blockhouses and our friend the armoured train was

seen approaching from Middelburg, whistling a friendly

warning to us. It came full speed as before, but only got to

the spot where the mine had been laid for it. There was a

loud explosion, something went up in the air and then the

shrill whistle stopped and all was silent.'(44)

By July 1901, the huge British force of about 25000 men had cleared the area in the eastern Transvaal south of the Delagoa Bay Railway and the scene of activity now lay to the north of the railway line where General Viljoen's men had retired after crossing the line on 27 June.(45)

Captain Hindon and his train wreckers faced mounting difficulties in attacking the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway Line: More and more blockhouses were being erected, connected to each other by a formidable network of barbed wire; deep trenches were being dug along both sides of the line; and increasing numbers of armoured trains were being brought into use. Thus, they decided to continue their train wrecking elsewhere and towards the end of July 1901 began moving in a westerly direction, destroying a train at Waterval about 30km north of Pretoria. By 9 August 1901 they reached the Pretoria-Pietersburg railway near Naboomspruit Station.(46)

From August 1901, attacks along the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway almost ceased. The line was so heavily defended as to make successful attacks almost impossible and certainly not worth the risks involved.

General Viljoen's men organised some expeditions to the Delagoa Bay Railway during November 1901 but their efforts met with little success. During one of these night raids on the line, they laid a mine near Hector's Spruit Station. While they were lying in ambush the next day, waiting for a train to come along, a British soldier discovered the mine, having noticed some traces of the ground having been disturbed, and removed the dynamite. Thereafter, sentries were doubled along the line, making attacks even more difficult.(47)

By the beginning of 1902, the situation facing the ZAR forces in the vicinity of the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway had deteriorated to such an extent that obtaining enough food and other supplies merely to exist had become a continual struggle. In January, several attempts were made at destroying or damaging the railway, but the defence of the line was so strong that almost all attempts failed. Under these conditions, even the most determined amongst the train wreckers decided to turn their attention to other lines.(48)

On 19 February 1902, the British columns marched from Pan Station on the Delagoa Bay line against two Boer laagers in the Bothasberg and on the following day, sixteen ZAR men were captured.(49)

Several railway accidents occurred during the last few months of the war, causing a great loss of life. For example, on 30 March 1902, 38 men of the Hampshire Regiment were killed when the driver lost control in descending a steep gradient near Barberton. These accidents were apparently due to negligence on the part of the railway staff and no evidence of sabotage of the line was found.(50)

In April 1902, the British troops under Bruce Hamilton began their sweeping movement from the Delagoa Bay railway to the Natal railway. All the garrisons along the Delagoa Bay railway had been greatly strengthened and five armoured trains were moved to that section where the Republican forces were expected to make their crossing. In spite of all these efforts on the part of the British forces, only three Boers were taken prisoner, most ofthem escaping into the Zuikerboschrand.(51)

Just before the conclusion of the Peace at Vereeniging in May 1902, Captain Hindon and several of his train wreckers surrendered to the British They were cleared of all infractions of the laws of war.(52) When Lord Kitchener stated that he doubted that Captain Hindon's train wrecking tactics could be justified under international rules of war, Captain Hindon defended his actions by replying that the British forces had adopted the same tactics earlier in the war: firstly, in Natal when General White had ordered that bridges and culverts be destroyed by dynamite in the vicinity of Ladysmith; secondly, when British troops had attacked and tried to derail trains on the Pretoria-Pietersburg line during the investment of Pretoria; and finally, when British troops belonging to Steinaecker's Horse had destroyed a train on the Delagoa Bay Railway near Komatipoort.(53)

References

1. H W Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume 1 (London, 1902), p 142.

2. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War Volume 1, p 147.

3. Smith-Dorrien, Memories of forty-eight years' service (London, 1925), pp 252-4.

4. Smith-Dorrien, Memories of forty-eight years' service, pp 260-2.

5. Ben Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War (1st Edition, London, 1902), pp 254-6.

6. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 313-19; see

also Smith-Dorrien, Memories of forty-eight years' service, pp 265-9.

7. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume I, p 363.

8. Gustav S Preller, Kaptein Hindon: Oorlogsavonture van 'n Baas

Verkenner (Pretoria, 1916), p 174; see also Viljoen, My

reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 488.

9. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 489: see also

Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 175.

10. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 175; see also Wilson, After

Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume 1, pp 363, 364.

11. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 175-7; see also Wilson, After

Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume 1, p 364.

12. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 177-8; see also Wilson, After

Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume 1, p 364.

13. Smith-Dorrien, Memories of forty-eight years' service, p 273;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 178-81.

14. Smith-Dorrien, Memories of forty-eight years' service, pp 274-9.

15. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 178-81.

16. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 183.

17. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 183.

18. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 183-4.

19. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 184.

20. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 184.

21. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 184.

22. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 184.

23. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 188-9.

24. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 322.

25. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 322-3;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 189.

26. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 323-4.

27. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 189, 190, 191.

28. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 192.

29. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 487.

30. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 488; see

also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 189.

31. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 490-3;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 191.

32. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 494; see

also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 191.

33. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 495; see

also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 191, 192.

34. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 380-1; see

also H W Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II (London, 1902), pp 619-620.

35. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 204.

36. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 204-5.

37. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 206.

38. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 206.

39. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 207.

40. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 210.

41. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, pp 621-2;

see also Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 207-210.

42. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 387.

43. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 382-3;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 204-210.

44. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, pp 383-7;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 209.

45. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p622;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 211.

46. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 212-224.

47. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 442; see

also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 429-430.

48. Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, p 442; see

also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 244-246.

49. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p442;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 256-7.

50. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 977.

51. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 990;

see also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 260-4.

52. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 260-4.

53. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 262.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org