The South African

The South African

by Allan Sinclair

The official war art collection located at the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg serves to commemorate the significant role played by South Africans during the Second World War (1959-1945). While important events undoubtedly took place on the many battlefields of the war where many people distinguished themselves in uniform, the importance of the Home Front, a critical front where important industries were developed to service the forces in the field, should not be overlooked. One South African war artist who took a particular interest in this local aspect of the war was Geoffrey Long (1916-1961). The following article will illustrate how Long used the visual arts to record the Home Front during the war.

Capt G K Long, War Artist

Portrait by Neville Lewis

(Cat 1768 SANMMH)

It has been said that Adolf Hitler laughed on hearing of South Africa's declaration of war on Germany on 6 September 1939. At that early stage, he may have had good reason to do so. In 1939, South Africa was ill-prepared to wage any war. The Union Defence Forces (UDF) were in a state of disarmament and the only industries really worthy of mention, apart from state industries such as ISCOR and ESCOM, were mining and agriculture. Most necessities were imported and there was no basic infrastructure for recruiting, supplying and training troops and labour. Yet, in time, 354 224 South Africans volunteered for service in the war and South Africa set up a training programme for pilots and other specialists and became an essential supplier of ammunition, vehicles and other equipment to the Allied cause.

The occupation of most of Europe by Germany led to South Africa losing many of her European trading partners. Britain, too, was in no position to continue to supply South Africa with necessities, which meant that the country had to become self-sufficient. As has already been mentioned, certain primary industries, such as ISCOR, ESCOM and the mines, were already in existence and, due to the highly developed system of roads and railways established to service the mines, secondary industries could be set up away from the main centres. South Africa was also in a position to utilise the expertise of people who organised, controlled and developed the technical and engineering resources available at the time. This was achieved through expanding existing industries to produce armaments and equipment alongside necessary civilian commodities which remained in demand.

ISCOR produced large amounts of iron and steel and the state railways took control of the production of explosives. These major industries laid the foundation for wartime production while the government called on other smaller industries to assist. Eventually, over 1 000 factories became involved in the war effort. The outcome ofthis was the eventual production of armoured cars, mortars, ammunition, howitzers, helmets, aircraft hangars, bridges, uniforms and other equipment. By the end of the war, South Africa had become a self-sufficient nation with a new economic infrastructure in a position to export finished products and manufactured goods.(1)

Geoffrey Long's interest in the industrialisation process

Geoffrey Kellet Long was an established artist by the time

the war broke our. Even before his appointment as an

official war artist in 1941, he had been commissioned by Dr

H I van der Bijl, the Director-General of War Supplies, to

undertake a series of drawings of the ISCOR steelworks.(2)

Long took an interest in the birth of the South African

industrial age, and wrote the following:

'Generations of the future may come to look upon complete industrialisation as a fait accompli: future artists will transfer a mature stage of its development to canvas. But what of the beginnings, the birth and the struggle now being made, passing unrecorded in the stress and urgency of war? The biography of our achievements will be incomplete, like that of a great man photographed only at the height of his fame. It is my sincere belief that a great deal will be lost if in our time we neglect to record the works and conceptions that are ours.'

'... There is also a new hero on the scene: a man newly acknowledged as a vital necessity. He is a man without the battle dress, the man in overalls behind the machine. This man has not yet had sufficient praise: the public still does not recognise sufficiently that his work is the work of the soldier. While the actual scenes of battle are already being glorified by painters and writers, the home front worker is not receiving the full recognition he deserves in the eyes of the people. He should become as familiar a figure as the soldier for the part he plays is equally great.'

'Because organised industry for war is a new front, the general masses are not so aware of it... I firmly believe that the present speed-up ofSouth African industry and the men who are fighting in this section of the war should be glorified and represented equally in the nation's annals. Their portrait, their contribution, deserves to be put before the public in every possible way, not only for immediate reasons of propaganda and psychological value, but that a record be kept for the future years. That this record be made, not only in writing and iii photography btit by pictorial representation... will provide an instant visual experience: they are more intimate, more selective than any photograph, and the result more dramatic.'

'Covering this aspect of the war activity could be work of tremendous importance, giving concrete expression of their service which would define their exact purpose to workers and public alike. No stone has been left unturned in England to bring this point home and subjects of the industrial front portrayed by artists hang side by side with scenes of the withdrawal from Dunkirk and battles of the Norwegian Campaign. They will go down to posterity in the Empire's history as one.'(3)

Examples of Long's works of art

Of the examples of Geoffrey Long's artworks in the official war art collection which illustrate the industrialisation process in South Africa, five were selected for discussion in this article. Three ofthese are drawings, while the other two are oil paintings.

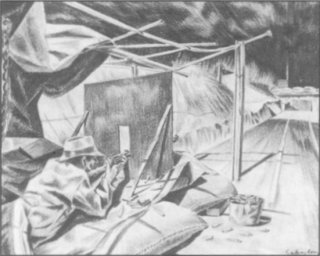

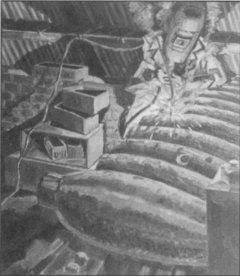

The first is a chalk drawing entitled Cutting armour plating. It depicts workers in a South African ordinance factory cutting armour plating to be used on armoured cars.(5)The second is a charcoal drawing entitled Dipping a gun barrel, and the scene is set in the same factory. Here molten metal, which has been poured into a gun barrel mould and has set but not yet cooled, is being quenched in a bath of oil to temper it. After this process has been completed, the newly produced gun barrel would be bored and rifled.(6)

Cutting armour plating.

2/Lt Geoffrey Long, 1941

(Cat No 1616, SANMMH)

Dipping a gun barrel.

Sketch by 2/Lt Geoffrey Long, 1941

(Photo: By courtesy: SANMMH)

Testing armour plating.

A sketch by 2/Lt Geoffrey Long

(Photo: By courtesy: SANMMH)

Home Front,

oil painting by war artist 2/Lt Geoffrey Long

(Photo: By courtesy: SANMMH)

Key man,

oil by Geoffrey Long

(Photo: By courtesy: SANMMH)

Through his paintings and drawings, Geoffrey Long was able to bring home the importance of the industrialisation process in South Africa and the ordinary people involved in maintaining war production here. There are many works in the Second World War Art Collection which depict the important roles played by South Africans who fought in the infantry, artillery, engineer, tank and medical corps as well as the air and naval forces. It is hoped that, by bringing to light the works which have formed the subject of this article, the role of the workers and industries will also not be forgotten.

References

1. J L Keene (ed), South Africans in World War Two: A pictorial

history, (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1995), pp 17-44.

2. N P C Huntingford, The Official World War Two works of Geoffrey

Long, (South African National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg, 1986), History of the artist.

3. File 920 - Long G K: 'Paper written by Long about the machine

and the man', in the South African National Museum of Military History Archives.

4. File 920 - Long G K: 'Statement issued by the Union Defence

Forces, 9 January 1942, re inter-factory exhibitions', in the South

African National Museum of Military History Archives.

5. 'Official World War Two Art Catalogue', Cat No 1616, at the

South African National Museum of Military History.

6. 'Official World War Two Art Catalogue', Cat No 1630, at the

South African National Museum of Military History.

7. 'Official World War Two Art Catalogue', Cat No 2003, at the

South African National Museum of Military History.

8. 'Official World War Two Art Catalogue', Cat No 1709, at the

South African National Museum of Military History.

9. 'Official World War Two Art Catalogue', Cat No 1745, at the

South African National Museum of Military History.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org