The South African

The South African

Military History Society

Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging

Military History Journal

Vol 11 No 5 - June 2000

The war experiences of Mike du Toit:

Eleven days in the Anglo-Boer War

by Pierre du Toit

Grandson

Introduction

Mechiel (Mike) Siewert Wiid du Toit was born in Hopetown,

Cape Colony, in 1868, the only son of the DRC churchwarden.

His father, a stern, uncompromising man, ran a school in

the mission grounds where Mike and his five sisters were

raised in the strict Calvinistic style of the time.

They were sent to the Huguenot Seminary in Wellington

for further education and Mike seems to have attended

SACS as well. After his father's death, he emigrated to the

Transvaal where he worked in the Surveyor-General's office.

Citizenship was bestowed upon him in l892. He was called

up during the jameson Raid (1895/6) and seems to have

enjoyed the military. In 1897 he married Kate Ferguson,

daughter of an American missionary teacher at the

Huguenot Seminary and joined the Staatsartillerie of the

Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR)

This is the story of the part that Mike du Toit played

in the armed forces of the ZAR doting the AngloBoer War,

pieced together by his grandson, Pierre, following many

years of research. It was a very short war for Mike, whose

service lasted precisely eleven days. The author had long

suspected that his grandfather had kept a diary and

fruitlessly scoured archives and military museums for it.

After the closure in 1994 of the Fort Klapperkop Museum

outside Pretoria, a Disposal Board was convened and the

diasy, which had been in the museum's possession all along

(despite enquiries by the author), ended up with the Rand

Light Infantry in Johannesburg. Thanks to Sergeant-Major

Peter Wells, the author was able to obtain a copy of the

diary which forms the basis of this article. The author

assumes that the diary was written in English for the

benefit of his grandmother who, although fluent in Dutch,

spoke English at home.

The war experiences of Mike du Toit

Following the Jameson Raid in 1895/6, the ZAR

Government began to take seriously the threat of British

imperialism and the personnel of the Staatsartillerie was

increased from 154 officers and men to 416 within months

after the capture of Jameson. This figure continued to rise

until the outbreak of war. State spending on defence, which

had been a mere £ 87 000 in 1895, leapt to £ 614 000 in

1897 and large quantities of weapons were imported from

Germany and France.

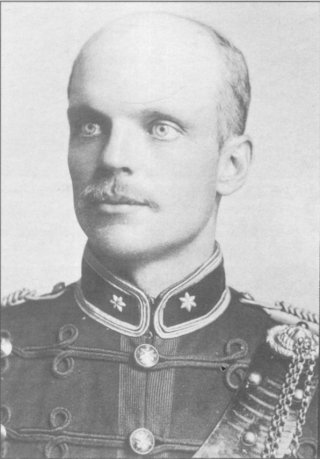

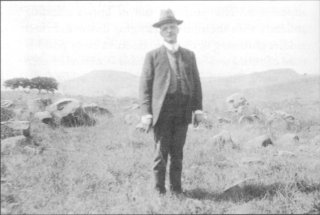

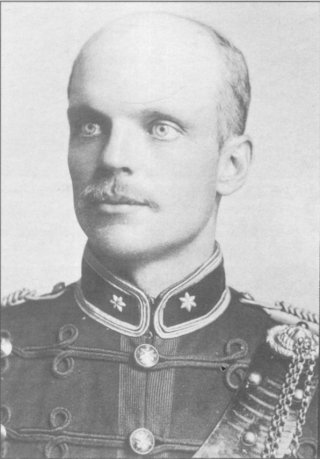

Mechiel (Mike) du Toit, ZAR Staatsartillerie

(Photo: National Cultural History Museum, NFI)

Katie du Toit (neé Ferguson, daughter of an American

missionary teacher at the Huguenot Seminary

(Photo: P du Toit)

Mike du Toit was accepted as a second lieutenant in the

ZAR Staatsartillerie after responding to an advertisement in

the Staatscourant and passing the examination. Subjects

required were Dutch, South African History, Geography,

Algebra, Geometry, Accounting, Nature Study and Artillery

Science. With his new bride, Katie, he moved into a house

in what is today known as Artillery Way, alongside the

headquarters building. He was assigned to the 'Franse'

(French) Battery, the third of the three batteries of the

Staatsartillerie and so called because it was equipped with six

75 mm breech-loading guns from the Schneider works in Le

Creusot, France. This weapon was very effective and

extremely difficult for the enemy to locate, as the low profile

and the use of smokeless powder made it almost invisible.

The main problem experienced with the gun was its brake,

which was insufficient and could not control the kick. The

other batteries were armed with 75 mm Krupp quick-firing

field gulls, the 55 mm siege guns known as 'Long Toms',

37 mm Maxim Nordenfeldt 'pom-poms' and various other

assorted weapons. Discipline in the Staatsartillerie was

similar to that of the Prussian Army, where a number of the

Boer officers had attended courses, and European instructors

had been seconded to mould the force into an efficient

fighting unit. Daily drill and inspection parades were

carried out and the garrisoning of the recently completed

Fort Schanskop formed part of their duties. In 1897, Mike

was promoted to full lieutenant with a salary of £ 275 per

annum. During the same year the battery appears to have

participated in manoeuvres near Rustenburg. Wives and

girlfriends were allowed to visit and during this time a

happy picnic was held in the area.

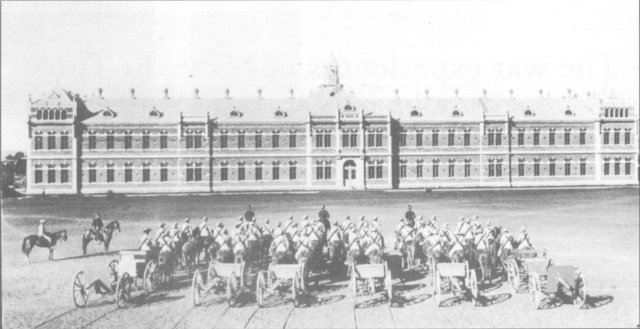

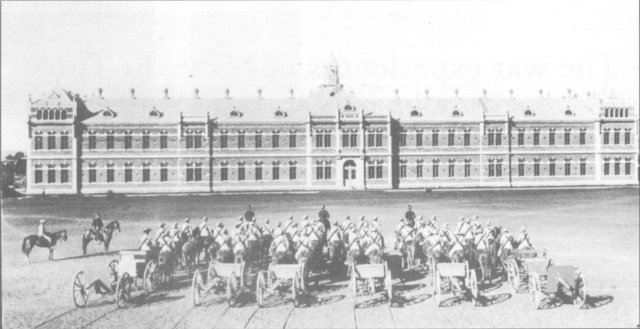

The 3rd Battery, ZAR Staatsartillerie, at Artillery Headquarters, Pretoria

(Photo: National Cultural History Museum, NFI)

In July 1898, the 3rd Battery of the Staatsartillerie

was sent to Swaziland to support thc police who were

attempting to arrest the Swazi king, Bunu. This followed

the murder of a senior induna in the royal kraal in April.

The special commissioner, Krogh, had received instructions

that Bunu must face trial and a summons had been duly

issued but ignored. A week later, Bunu had arrived at the

courthouse with his impis in full battle regalia,

whistling, rattling their spears and singing war songs. When

information reached Pretoria that the whole of Swaziland,

with the support of Dinizulu, was mobilising, Piet Joubert

was dispatched with 1 300 commandos and artillery to

Bremersdorp to restore order. Bunu still refused to hand

himself over and a further 700 men were sent to reinforce

the garrison. The Staatsartillerie constructed a fort on an

exposed rise across the Mzimnene River to the east of the

town. The guns were positioned on platforms 2,4 metres

high, providing a 360 degree field of fire, and surrounded

by a 1,5 metre high earth and sandbag breastwork enclosed

by a trench which was 1,2 metres deep and 1,8 metres wide.

The fort at Bremersdorp (Manzini) during the 1898 Swaziland Expedition

(Photo: National Cultural History Museum, NFI)

In a letter to Katie, Mike wrote:

'I had the honour of shaking hands with her dusky

Majesty the Queen - she is a very fine looking

woman with the smell of a pole-cat about her. I wish

you could see how her court ladies do up their hair.

I shall try to get a collection of photos of native

studies and forward them on to you. Some of the

kraal ladies are as nude as my hand with the most

perfect figures imaginable.'

The letter also contains a sketch of the fort and shows the

lack of security that prevailed.

As with most military operations, boredom was the main

enemy during the campaign and Mike described it as one

of his biggest problems. Bunu fled to Natal and, after much

negotiating between the British and Boer governments,

stood trial in September. He was found not guilty of

murder but guilty of inciting public violence and fined

£ 500 with expenses of £ 1 000 to be paid to the Transvaal

and £ 146 to Natal.

Back in Pretoria, the Staatsartillerie began publication of

their own monthly paper Voorwaarts!, Maandblad van het

Corps Staatsartillerie, with Mike as the editor and Katie, an

accomplished artist, providing the artwork. A banner for the

paper, depicting a cherub, with sword in hand, riding a

shell propelled by another cherub, is dated March 1899. All

eight pages are hand-written. Articles range from the battle

of Laings Nek, a facsimile of Dingaan's land grant to Retief

(in English) and even a correspondence section where a

gunner seeks advice on whether life insurance is Biblically

acceptable. The language used in the paper is generally

Dutch, but occasionally this changes into Afrikaans and it

is interesting to note the development of the language.

Another of Katie's sketches of the time survives. With the

title 'Alarm', it illustrates the falling in of the gunners on

parade. Written across the bottom of this sketch in an

extremely crude hand are the words 'Staats Artillerie Kamp'.

How this scrawl got onto the picture remains a mystery.

The names of various officers appears on the back.

Voorwaarts did not survive long and was soon swallowed

up by other activities as the Corps prepared for the coming

struggle.

In September Mike wrote a letter, in English, to his

sister:

'Art. Camp

Thursday 28th

My dearest sister,

As we are leaving for the frontier tonight I

thought a few lines from me would be welcome.

Ours and the 1st Battery (12 guns) are going to the

Natal border where we expect the heaviest fighting

will be, maar my zuster, ons moed is goed, want onz

zaak is rechtvaardig. I will try to write you now &

again from the seat of war. I returned from Natal

Tuesday & was very thankful to escape with a whole

skin. Give my fondest love to all our dear ones &

with very much love to you and Piet, & don't you

get low spirited Hester. Remember that one Boer is

equal to 10 Englishmen.

Your loving brother

Mike'

His wife also wrote to the same sister:

'Mike has been down to Natal as a spy, he left on

Friday and got back on Tuesday, it was very

dangerous work, but he did it splendidly. They have

been trying to find out one particular thing, and had

sent nine different men already without any success,

& Mike got the information for them.'

Quite what the spying trip entailed is unknown but it is

interesting to note the following undated entry in his diary:

| '18 Hussars |

550 |

| 5 Lancers |

550 |

| 13 RA |

180 |

| 42 |

+/-190 |

| 67 |

+/-190 |

| Leic |

916 |

| Dub Fus |

904 |

| Royal Irish |

1 100 |

| Mount Inf Lec |

300 |

| Indians |

300 |

| |

5 180 |

A fairly accurate assessment of the British force at Dundee!

In early September, it was reported that the British

cabinet had decided to send a further 8 000 troops to

reinforce Natal. President Kruger of the ZAR became

convinced that war was imminent. He needed the Free State

burghers as allies, but President Steyn remained uncertain,

feeling that a peacefnl solution was still possible. Smuts was

instructed to draw up plans for a military offensive and his

plan was for a Blitzkrieg-type thrust deep into Natal

and the occupation of Durban before the arrival of reinforcements

from Britain. On 28 September 1899, President Kruger

decided that he could wait no longer and ordered mobilisation

and the drafting of an ultimatum for presentation to the

British government. President Steyn continued

to hold back, asking for the ultimatum to be redrafted.

Kruger would not be moved on this and on 2 October the

Free State mobilised. The ultimatum was finally presented

to the British agent at 17.00 on 9 October, the same day

that British troops began disembarking in Durban. Smuts's

planned blitzkrieg had lost its advantage.

At the artillery camp, action was feverish on 28 September

1899. Captain Pretorius, in charge of the 3rd Battery,

had his men up before dawn. They paraded and then

marched past the President's house and up Market Street to

the station. Here the scene was festive, the artillery band

under Lieutenant Maggs played stirring music, women wore

their best clothes and hundreds of guests and well wishers

came to see the departure of the contingent. Loading

commenced and sixty men, six guns, eight ammunition

wagons and 105 horses were entrained. Mike kissed his by

then pregnant wife goodbye and then, to the strains of the

Volkslied and the applause of the bystanders, the train

pulled out. After a journey of three monotonous days,

interspersed with interminable halts, the train finally pulled

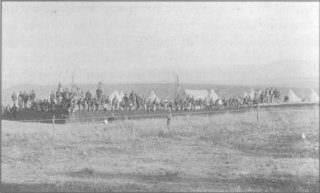

up at Sandspruit, a siding about 15 km from the Natal

border. As far as the eye could see, the veld was speckled

with tents and wagon laagers as new burghers arrived in a

continuous stream. The horses and equipment were off-loaded

and a camp was pitched. The 3rd Battery had a very

capable veterinary officer (paardenarts) in the person of

Arnold Theiler, who would later gain world renown as the

founder of Onderstepoort. The republican flag and a large

marquee on the left of the tracks announced the presence of

the commandant-general, Piet Joubert, and councils of war

were already in progress.

For the next few days a holiday atmosphere prevailed,

hunting parties went out and braaivleis and Boeremusiek

were the order of the day.

An entry in Mike du Toit's diary for 10 October

describes the scene:

'President's birthday - about 1 200 mounted

men of the Heidelberg Commando paraded and

drew up in front of the General's tent where he

addressed them. Our band then struck the Volkslied

& 3 roaring cheers were given for the Pres. & Genl

Maggs then struck up a spirited march & amidst

cheers the Heidelbergers departed. It is marvellous

how light spirited everyone is, in spite of all the

hardships. We had a very severe hailstorm this

morning & a boisterous gale blew all day I expect

tonight will be bitterly cold.'

The war council was already experiencing the disagreement

that was to plague the Boer forces throughout the

war. Every general wanted his own artillery detachment and

the Staatsartillerie ceased to exist as a cohesive unit as

guns and men were allotted piecemeal to the various commanders.

Mike and others of the 1st and 3rd batteries were attached

to the 2 000-strong commando of General Lukas Meyer.

General Joubert addressed the men from the saddle.

Pointing at Majuba, which was clearly visible from the

camp, and to Natal beyond, he reminded them how that

country had been stolen from their forefathers by the

English and of the victory they had achieved on the

mountain in 1881. He urged them to take it back.

The Boers' plan of attack was to isolate the British

garrisons in central Natal and then to press on to Durban.

The Transvaal forces were divided into three columns: The

left and centre were to attack General Penn Symons at

Dundee whilst the right was to link up with the Freestaters

and attack General White at Ladysmith.

An entry in Mike du Toit's diary for 11 October reads:

'We got orders to pack up everything this morning

so as to be ready to start at 1 o'clock. We got away at

2 & after going about 1 mile [1,6 km] the order

came to outspan. The major & Capt P have gone to

the generals to hear about England's reply to the

ultimatum, the time of which expires at 5 pm. I

expect them back at about 6, & we shall then

probably know if there is to be war or not. The wind

is bitterly cold and I expect we shall have a freezing

night and without tents too for everything is packed

away.'

General White, the British commander in Natal, who had

arrived from India on 7 October, was never in favour of the

positions adopted by General Penn Symons, dividing his

force between the two towns. He wished to consolidate his

force behind the Thukela and await the arrival of Bullet, the

commander-in-chief, and his reinforcements then on the

high seas. The Natal Governor, much influenced by the

debunked Randlords who had sought refuge in Pietermaritzburg,

placed White under immense pressure to save

the coal fields and advised that any withdrawal would be

construed by the still rumbling Zulu impis as a sign of

weakness. White decided to leave the troops where they

were.

On the morning of 12 October 1899, the great advance

began. The right hand column, under the command of the

64 year old General Kock had special orders to cut the

railway line between Dundee and Ladysmith and occupy

the Biggarsberg Pass. The centre, comprising the Heidelberg,

Pretoria and Boksburg commandos under General 'Maroela'

Erasmus, were to take Newcastle and then to attack the

garrison at Dundee from the north-west. The left column

under General Lukas Meyer was to follow the Natal border

to De Jagersdrift and then to cross into Natal and attack

the garrison at Dundee from the north-east. Strategically,

the plan was excellent and should isolate the two

garrisons.

On 12 October, Mike wrote in his diary:

'At Volksrust. Old England wants to fight so we

are going to oblige her. The wagons & horsemen

have been arriving in one continuous stream for over

three hours & are still pouring in. There must be

over 10 000 men here already. A report is being

spread here that the Free Staters crossed the Natal

border this morning. We expect to go over tomorrow,

the major has just been sent for by the general,

so I expect we will know definitely soon.'

The entry for 15 October reads:

'The last three days have been hard ones for

everyone. We left Volksrust on Thursday afternoon

& after going for about two hours a fearful rainstorm

came on & as our provision wagons were too

overloaded we left them behind to follow slowly. The

rain came down in such torrents that I was

compelled to stop the battery & outspan. Most of

the men sat against the gun wheels all night. Fred

R[othmann] and I managed to get a little sleep on

the sopping ground. The whole of Friday was

showery & by evening every bit of my clothes was

wet. In spite of this, I managed to put in a good

night. Yesterday, the sun came through & we got all

our things dry. One of the provision wagons also

caught up with us, so that everyone was in good

humour again after feeding the inner man. Last

night, we came to this place - it belongs to an uncle

of Fred's, but he is away on commando. This

afternoon, we go on to Doornberg where we have to

wait for further orders from Genl Meyer. Yesterday

we heard about the Mafeking encounter & this

morning we heard that 2 000 troops are coming

down to meet us at the Buffels R[iver] Drift.'

Fred F L Rothmann was an old family friend, who seems

to have 'attached' himself to the artillery unit in order to be

with his colleague. The bad weather bogged everything

down. The guns were pulled through, but with insufficient

ammunition, and the horses, mules and cattle were so

knocked up that they could not go on. The expected

reinforcements were the commandos from Pier Retief and

Ermelo, as well as Schalk Burger's Eastern Transvaal

commandos and the Swaziland Police.

On 17 October, Mike du Toit wrote:

'At Doornberg. Yesterday the major sent me in to

Utrecht to buy goods & from there I wired to

K[athy] & had a good breakfast at a real table. When

I returned the artillery had already left for this place

so I had to put in about 20 miles [32 km] quick

trotting. I had taken cold the day before & now

began to feel the effects of it. Last night, I was utterly

miserable & took to my bed on the ground at 6 pm.

It was a real pleasure to see the kindness of the men

when they saw that I was sick. Lottering was

convinced that the only thing for me was a hot

punch & he managed to make some very drinkable

stuff. I am sure it did me good for I had a good night

and am feeling better this morning. When I woke

this morning Mrs Dr B was lying on the ground

about 10 yds [9,14 metres] off, fast asleep. She had

come on horseback in the night & wanted to join us

but I doubt very much if the major will accept her

services at present. A report has just come in that

heavy canon firing [was] heard Ladysmith way

yesterday, so it is possible that Genl Kock and [the]

Free Staters have tackled that town. We are about 15

miles [24 km] distant from Dundee & are expecting

Genl Meyer here this evening, when I trust he will

let us go in at once for there is a certain amount of

dissatisfaction amongst the burghers at this - to

them - reasonless delay.'

The war was already seven days old and still not a shot

had been fired in anger. The column had advanced some 90

kilometres and the Boers, especially the younger ones, were

growing increasingly disenchanted at the lack of action.

Commandant-General Piet Joubert, with the railway at his

disposal, had only advanced 45 kilometres as far as

Newcastle.

Mike's diary entry for 18 October reads:

'Our ammunition wagons have still not turned

up yet so we are still waiting here (near Doornberg).

From the Kop the English Camp at Dundee is quite

visible. They seem to be about 4 000 strong & we

hear that they are very strong in artillery. Our men

are getting very sick.'

The diary continues:

'18th. Eersteling - near De Jagersdrift. At last the

fortified koppies around Dundee are plainly visible

& we are only 4 miles [6,4 km] distant from the

N[atal] border. It is full moon tonight and I expect

the burghers will send out a strong guard for it is not

impossible that the English might try to surprise us.

Report says that there are a little over 5 000 troops in

Dundee with +/- 30 guns.'

On the evening of 19 October, Meyer's force of about

4 000 men assembled at De Jagersdrift and, following a

stirring sermon by Dominee Anderssen of Vryheid, crossed

the Buffalo River into Natal. Guided by a friendly Natalian,

they made their way in the pouring rain across the veld and,

after a brief engagement with a British picket, arrived at the

back of Talana at 03.30 in the morning. Two Krupp guns

and Mike's Creusot 75 mm gun were labouriously hauled

to the summit. Permission to build breastworks was denied

by Meyer. As dawn broke and a gentle breeze cleared the

mist, the enemy camp became clearly visible in the valley

below.

During the night and with great difficulty, General

Erasmus had managed to get his men to the top of the

1 600 metre high Impati Mountain to the north-west of the

town, but the crown was buried in the clouds. In the British

camp, the troops had paraded as usual at 05.00 and were

told to prepare for infantry training. Movement on Talana

caused an uneasy stir and confusion. Human figures were

easily visible, silhouetted against the dawn sky, but were

they members of the town guard, their own picket, or the

Boers? Meyer viewed the unease in the British camp and

kept glancing at Impati from whence the order to attack

should come. After much prompting from the burghers he

eventually gave the order for the artillery to open fire. As the

first shells crashed amongst the British tents, men were seen

scurrying in all directions and Penn Symons is reported as

having said: 'Damned impudence to start shelling before

breakfast!' On top of the hill, the Boer gunners gave it

everything they had. Much of the ammunition was poor

and the percussion fuses failed to explode in the wet

ground. The British artillery was quick to organise and,

after finding that they were out of range, they galloped

through the town and deployed at a range of 2 000 yards

[1 828 metres]. The hilltop was raked by shrapnel and,

without the protection of breastworks and silhouetted

against the eastern skyline, the Boers were forced to pull

back their guns.

At about this time, Mike du Toit was struck below the

left knee by a piece of shrapnel and the bone was broken in

two places. He fell next to his gun, where his friend, Fred

Rothmann, found him trying to crawl to safety from the

hail of shrapnel.

After the war, Mike described the event:

'As I lay by the canon, half conscious, I became

aware of a long slab of a man with a pipe in his

mouth at my side and he indicated that he was going

to carry me piggyback. He manoeuvred me onto his

back and we set off, shells bursting all around us.

One burst so close that it threw both of us to the

ground. All I could hear was Fred cursing the

English because his pipe went missing when he fell.

After finding it he again managed to struggle me

onto his back and on we went.

Fred Rothmann carried him for a few hundred metres

over the stony ground to safety behind some large boulders,

An ambulance arrived shortly thereafter and the injured

man was taken in a stretcher to a farmhouse at the back of

the hill that had been converted into a field hospital. Here

he was placed in the care of a Dr van der Metwe, whose

initial reaction was to amputate, but decided to defer his

decision. Dr C O Moorhead, a general practitioner from

Middelburg, Transvaal, the son of a British military surgeon

and born in India, described the scene at this field hospital,

today known as Thornley Farm, where he was serving with

the Boers:

'The farmhouse, a solid building with stone walls

and stone offices, presented an extraordinary

appearance. The yard was full of horses standing

patiently with their bridles hanging down and their

saddles glistening in the rain. Boers in every possible

state of mind were crowded about - wounded men

were being helped in by their friends, carried down

in blankets or overcoats from the hill above, where

the rifles still cracked out. Shrapnel whizzed noisily

overhead now and then. All looked angry and

frightened. I stepped into the house. Right opposite

me, crumpled in the passage lay the body of Field

Cornet Joubert of the Middelburgers, a little round

hole in the centre of his four-coloured hatband. In a

room to the right the little German artillery doctor

welcomed us warmly and asked for dressings. On a

large bed lay Lt du Toit, with whom I had ridden a

couple of days previously, his leg shattered by

shrapnel. Beside him lay an artillery private shot

through both lungs. The floor was covered with

wounded, pools of water and blood lay everywhere.

Every room was full of groaning forms. I broke into

the tiny pantry and established myself there and for

an hour and more was busy dressing man after man

as they were brought in. The occasional scream of a

shell over the roof told me the fight was not yet over.

There was at length a moment's breathing space, and

I went outside to try and see what was going on. I

noticed a young British officer with a bandaged

hand, Lt Weldon of the 1st Leicestershire. Presently

I saw him strolling nonchalantly away round the hill.

A stout red-faced commandant ordered the burghers

to bring him back. "Leave your weapons here, he is

unarmed," he added further, a kindly trait at such a

moment. The confusion in the hospital all this time

was indescribable. There were only two stretchers

available and wounded men were constantly coming

in. They were laid on the floor until they lay

touching one another all over the house. They were

all wet and sopping, there were no dry clothes or

bedding available but fortunately the kitchen kept

going all day and always provided something warm.

Lt du Toit told me he and an artillery man named

Schultz had worked a Krupp and a Pom Pom until

they were both struck down at the same time. The

next thing I remember was a clear English voice

asking who was in charge of the hospital and the

voice of Dr van der Merwe modestly replying that he

thought he was. I went out and found a flushed and

panting subaltern of the Dublin Fusiliers, his helmet

pushed back, a sword in one hand and a revolver in

the other. At his back [was] half a company of grimy,

panting soldiers with fixed bayonets. The British had

taken possession, the hill was theirs. Some British

wounded now came in but room was found with the

greatest difficulty, there were over 80 people lying in

one small house. It is interesting to note that the

British fired 1 237 rounds of shell and the troops

82 000 rounds of ball cartridge. Therefore at this

battle it took about 8 oz shrapnel and over 500 Lee

Metford bullets to account for every Transvaaler.'

After a fierce struggle, the British had driven the Boers

off Talana and the burghers were streaming back across the

veld to De Jagersdrift. It was at best a Pyrrhic victory for the

British troops. Totally exhausted, they had been on their

feet without food for ten hours and were in no condition to

pursue the Boers. Their casualty figures were horrendous:

51 dead and dying (including General Penn Symons), 203

wounded and 220 missing. General Yule, who had assumed

command after Symons was mortally wounded, received

reports of large bodies of Boers advancing on the town from

the opposite direction and ordered his men back to camp.

Throughout the battle, General Erasmus, on top of

Impati, had stood impassively, sucking on his pipe,

glowering into the mist. The sound of the battle below

reverberated off the surrounding hills and despite the

pleadings of his men to lead them into battle, he still took

no action. No satisfactory explanation has ever been given

for Erasmus' inactivity and the failure of General Kock to

attack along the railway from Glencoe junction, but it may

well have been the personality clashes that existed. There is

no doubt that, had the three pronged co-ordinated attack

taken place as planned, the British force would have been

annihilated.

On the morning of 21 October the Boers positioned a

155 mm Long Tom siege gun on the slopes of Mount

Impati and began shelling the British camp at a range of

10 000 yards [9 140 metres]. British intelligence had

reported these guns, originally used for the defence of

Pretoria, as immovable and their appearance on the hill

came as a nasty shock to the new British commanding

officer, General Yule. He spent the day moving his men

out of the range of the 80-pound shells, before abandoning

his hospitals and the wounded, and slipping away during

the night. The same day, the Boers from Mount Impati

occupied Dundee.

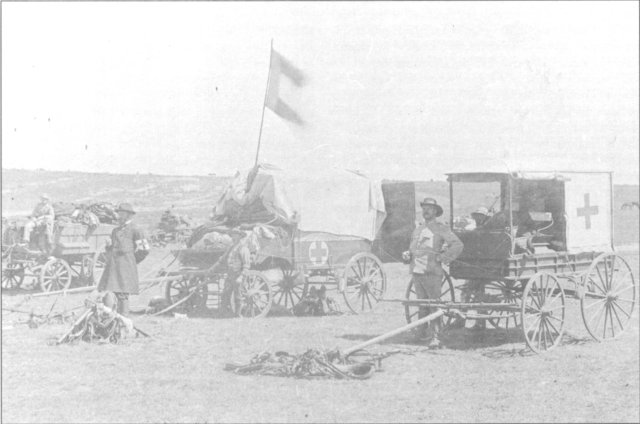

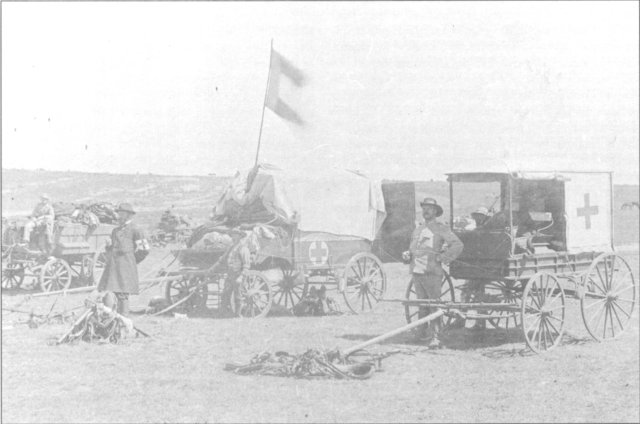

A Boer field ambulance

(Photo: By courtesy, War Museum of the Boer republics, Bloemfontein)

In the Boer hospital behind the hill, Fred Rothmann sat

with Mike throughout the night. The next morning, the

Boer doctors loaded the wounded onto wagons and sent

them to the field ambulance at De Jagersdrift. Fred,

accompanying Mike, described the scene in a letter to his

sister, written in English. These are extracts:

'DeJagersdrif, 25 October 1899

I write from our ambulance station, where our

wounded have been brought following the battle. I

managed to get a room for Mike on his own. It was

very fortunate, because I don't know what we would

have done in a larger room with other people. He is

in continuous pain and I sit with him day and night.

He can only sleep with morphine and this is the only

time I get any sleep. We have plenty of food but

need trained nurses desperately. A British doctor has

come out from Dundee, and after consulting with

our doctors, agreed to take the badly wounded into

the hospital in Dundee. It will be impossible for

Mike to go the fifteen miles by wagon and this

British doctor has kindly offered to have him

transported in a dhoolie.'

Mike composed a telegram to the State Secretary, Reitz,

asking for his sister Leonora, a trained nurse, to be sent to

look after him. He also wired Katie and the telegram was

sent by the ever faithful Fred Rothmann:

'There is a chance of [my] leg being amputated, [I]

am leaving for Dundee tomorrow. See President for

free pass for [your]self and Leo. Come through Natal

to Dundee. Can get cottage for us. Bring water

pillows for bedsores. Fred is with me, bring Annie

[Fred's sister].'

The British doctor referred to in the extract above was

Surgeon-Major F A B Daly, an Australian serving in the

British hospital which had been abandoned by the

retreating General Yule. Daly published his memoirs many

years after the war and recounted the incident. After

consultation with the Boer doctors, Mike was assured that

his leg could be saved, provided he was moved to the

hospital that had been set up in the Scandinavian mission

in Dundee. He did not seem to think that he could survive

the journey and the final entry in his diary was a letter

addressed to Katie in a different handwriting:

'My dear old Katie,

The d[octo]rs think that I should be carried to

Dundee, a distance of 15 miles [24 km] to have the

x-rays tried on my leg. Personally I don't think I can

live through this journey that is why I am dictating

these lines to Fred. Everyone has been most kind to

me. Be sure Katie that if I do die tomorrow my last

thoughts will be of you.

Fondest love

Mike'

Mike du Toit stood the journey well and was housed in

the home of the local minister, together with a number of

wounded British officers. He was of great assistance to Dr

Daly in procuring supplies from the local commandant and

even managed to organise 297 sheep for the hospital. Upon

his return to Pretoria, Mike spoke so highly of Dr Daly that

Louis Botha presented a set of trophy kudu horns to the

doctor.

On 10 November, Mike's condition was so improved

that he was fit to travel and a special train with an

ambulance carriage conveyed him, Katie and Leonora to

Elandslaagte, where they remained for about ten days and

could clearly hear the booming of the artillery as Ladysmith

was besieged. No more wounded were received and the

train was required to move up to Modderspruit, closer to

the front. The doctor thought that Mike should be sent to

hospital in Pretoria and so they were placed in a van and

attached to an ordinary train.

In later years, Mike du Toit (above) revisited the exact site

where he was injured during the Anglo-Boer War.

(Photo: By courtesy of P du Toit)

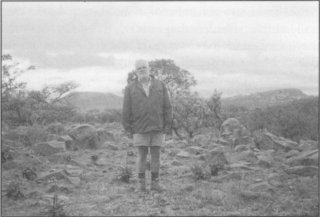

The author recently visited the site where his grandfather was

injured in battle during the Anglo-Boer War.

(Photo: By courtesy of P du Toit)

On 17 November, Izaac von Alphen used his newly

acquired x-ray apparatus to assist doctors von der Horst and

von Gernet in removing a piece of shrapnel and two bullets

from Mike's leg. When the British occupied Pretoria on

6 June 1900, Mike, back in uniform and only able to walk

with difficulty, was taken prisoner. On 26 July, he was

granted parole and, with Katie and their recently born son

Louis, was given permission to proceed to Hopetown to stay

with his brother-in-law, Pieter du Toit. From there, they

moved to Gordons' Bay, where they appear to have been

when the war ended. Mike had to report to the Military

Governor at the Castle twice a month, which entailed a

four-day horse-cart journey across the Cape flats.

The years after the war were difficult until Mike du Toit

met his wartime colleague, J B M Hertzog, and obtained

the post of Police Commissioner in the Orange River

Colony. He remained in police service until 1928 when he

contested and won the Pretoria West seat for the National

Party. He continued in politics until shortly before his

death in 1939.

Bibliography

Amery, L S (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902

Breytenbach, J H, Die geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog in Suid-Afrika.

Daly, F A B, Boer War memoirs.

Die Brandwag, June - October 1910.

Die Volkstem, October - November 1899.

Du Toit, M S W, A 1838, W77, State Archives, Pretoria.

Gutsche, Thelma, There was a man.

Haupt, D J, Die Staatsartillerie van die Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek.

Huisgenoot, 9 October 1925.

Kommando, October 1950, June 1954.

Matsebula, J S M, A history ofSwaziland.

M E R, Oorlogsdagboek van 'n Transvaalse burger te velde, 1900-1901.

M E R, My beskeie deel.

Militaria, 6 February 1976.

Pakenham, T, The Boer War.

Preller, G S, Dr, Talana.

Reitz, D, Commando: A Boer journal of the Anglo-Boer War.

Rothmann, F L, A 1877, A321, State Archives, Pretoria.

Suter, F A, Dr, Unter der Schweizerischen Roten Kreuz im Burenkriege.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's

Home page

South African

Military History Society /

scribe@samilitaryhistory.org

The South African

The South African