The South African

The South African

by Nosipho Nkuna

Nosipho (Pearl) Nkuna is an education officer at the South African National Museum of Military HistoryAuthor's note: The following article focuses on the involvement of black South Africans in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902. The term 'black', used in this article, refers specifically to black South Africans and does not include Coloureds and Indians.

Although the Anglo-Boer War was primarily a war between the British and the Boers, other population groups in South Africa, like the Zulu, Xhosa, Bakgatla, Shangaan, Sotho, Swazi and Basotho, became embroiled in what was initially termed the 'White Man's 'War'.. There was an unwritten agreement between the leaders of the Boers and the British that this war would be a white man's war and that blacks should not be armed for the struggle. In spite of this, however, there are photographs that attest to the contribution made by blacks in both combatant and non-combatant roles during the war. Blacks were employed in a wide variety of roles, as trench diggers, scouts, despatch runners, cattle-raiders, drivers, labourers and trackers, and they were used in the construction of forts, the transportation of balloons that were used for reconnaissance work, and also as agterryers and auxiliaries.

Agterryers were either conscripted by the Boers or joined the commandos voluntarily. The Boers utilized agterryers for guarding spare ammunition, looking after the horses, cooking, collecting firewood and loading firearms. Not only were auxiliaries used in a labour capacity, but they were also used in fighting. Some photographs of Boer commandos and their agterryers attest to the fact that auxiliaries were armed during the war. Some of the Boers had a very strong attachment to their servants who had served them before the commencement of the war. Fransjohan Pretorius worked out the numeric ratio and concluded that a ratio of 1:4 or even 1:5 (agterryer pro rata to Boers) may be taken as realistic.(1) Pretorius has suggested that roughly 15 000 agterryers served in the war.(2) In his diary, C A Cronjé wrote about his agterryer, Kleinbooi Sabalana, and confirmed that he was given a rifle and fought in many battles. Keinbooi was only 15 years old when he joined the commandos, but proved himself to be brave in these battles.(3)

On 10 September 1899, C Bird, the Principal Under-Secretary for Native Affairs in Natal, instructed all white magistrates in the Natal Colony to appeal to Zulu ama-khosi to remain neutral in case of war between the Boers and the British.(4) In the kingdom of Zululand, this agreement was only observed until January 1900, when the Boers captured the Nquthu Magistracy, including the fifty Zulu policemen who were defending it.(5)

For many black people in South Africa, active involvement in the Anglo-Boer War was voluntary. In some cases, for instance, the Swazi wanted to settle old scores with the Boers who had confiscated their land before the war. Thus the Swazi people entered the war with a specific aim of reclaiming their land from the Boers.

Black despatch runners and scouts were an essential part ofthe system of field communication. R C A Samuelson, a member of the Natal Carbineers and the brother of the under-secretary for Native Affairs, was sent to Driefontein and Edendale to raise a unit of men for intelligence work, to be known as the Zululand Native Scouts. Samuelson served as an officer of the Natal Carbineers and not as the captain in charge of these men. The success of the unit indicates that these men worked amicably together and had a good relationship with each other.

Driefontein Group No 1. Men such as Stephen Mini and Khambule

recruited amakholwa (Christians) to serve as scouts during

the siege of Ladysmith. Samuelson served with these men as a Carbineer

officer.

(Samuelson, Long, long ago, p 117)

The Boers employed a large number of black scouts. Information conveyed to the commandos by the black scouts was remarkably accurate and it was also transmitted with extraordinary rapidity. On the British side, black scouts were used with particular success during the later stages of the war when, to counter the guerrilla tactics of the Boer commandos, the British Army divided its men into smaller and more mobile columns, each of which depended for its success upon reliable information about the enemy's movements.

Black men employed to guard a blockhouse

(SANMMH)

A group of armed black scouts attached to the 4th Battalion

Scottish Rifles Mounted Infantry at Boshof. By the end of 1901

almost all black scouts with the British forces bore firearms

(Warwick The South African War, p 198).

During the siege of Ladysmith, November 1899 to February 1900, the scouts played a particularly important role. Black scouts regularly came under fire, but, unlike the Colonial scouts, they were initially not allowed to carry arms.(7) By the end of 1901, however, almost all scouts attached to the British columns bore firearms.

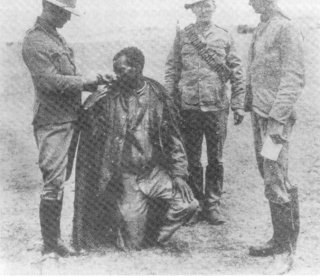

A black despatch runner is prepared for sending a message to Ladysmith.

Despatch runners played a vital role on both sides during the war.

(Warwick The South African War, p 195).

Blacks in concentration camps

When the British resorted to the scorched earth policy of burning Boer farms, blacks were also removed from farms and accommodated in separate concentration camps. The decision to move them to these camps was not a humanitarian gesture by the British. The blacks had to be cleared from the land to prevent the Boers from obtaining assistance, supplies and labour from them. In most concentration camps, conditions worsened every day for the black inmates. There was no material available with which to build proper housing and the blacks had to acquire on their own the little that was naturally at hand. There was also no sanitation or fresh water facilities in the camps and medical care for black inmates was very limited. By the end of the war, thousands of black inmates had died from typhoid, diarrhoea and dysentery because of the appalling conditions under which they had lived.

A mother and child interned in a refugee camp in Klerksdorp

They received insufficient food and shelter

(After Pretoria p 559)

After the war

The failure to recognise the contribution made by blacks in the war was evident by the non-issue of medals after the war, which can he attrihuted to three factors: Firstly, the blacks had served as non-enlisted soldiers and, according to the British Army regulations, only enlisted soldiers could receive medals. Secondly, the decision not to issue medals to blacks was a political one in the sense that it was felt that the Boers might have felt insecure and angry had blacks been issued with medals. After the war, the British government went to great lengths to attempt to conciliate Boer opinion and, by awarding medals to blacks and thereby officially recognising the contribution made by them in the war, these efforts would have been endangered. Thirdly, the non-issuing of medals to Blacks can also be attributed to the problems of bureaucracy. In Natal, for example, Samuelson, who had recruited the black scouts, went as far as drawing up a list of all the scouts who were entitled to receive medals, but the matter was dragged from one official to the next and, ultimately, it was dropped altogether.

Solomon Mojela, who lived in Evaton near Vereeniging (where the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging was signed in 1902), was conscripted by the Boers to join the war. His story was reported in the Sunday Times of 14 February 1982. His job had been to look after the Boer horses. In 1982, the South African Legion was going to honour Mr Mojela with a commemorative medal, but a few days before he was due to receive it, the old veteran passed away. Mr Mojela was one of many black veterans who were unknown and never rewarded for their contribution in the Anglo-Boer War.

In the Journal of Military Medals, No 21, March 1983, it is stated that some of the black units qualified for the Queen's South Africa Medal. These units included the Herschell Native Police, the Matatiele Native Contingent, the Tembu Levies and the Kruisfontein Native Scouts. It has not yet been verified whether these units actually received the medal; their names are not recorded.

In Natal, the commander-in-chief of the British Army, Lord Roberts, made it clear that the black scouts should receive bronze and not silver medals.(11) This decision came as a shock to those black scouts who had served and dedicated their lives to the war and they refused to accept the bronze medals, which they regarded as inferior. Samuelson, who had raised units of black scouts during the war, also expected his men to receive medals which never came forth.

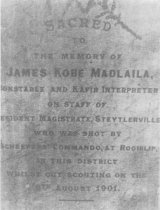

During the Anglo-Boer War, many blacks who had served as combatants or non-combatants lost their lives. The official statistics of blacks killed in action are inaccurate. According to Nasson, in the Cape Colony, most of the bodies were dumped in unmarked graves.(12) Constable James Kobe Madlaila of Steytlerville was one of the few scouts who had a tombstone over his grave with his name clearly inscribed on it.

The tombstone of James Kobe Matlaila from Steytlerville

in the Cape Colony. Madlaila was one of the Black scouts

who received a burial and tombstone during the Anglo-Boer War.

(Nasson, Abraham Esau's War p 185).

Although the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) was initially termed a 'white man's war', large numbers of black people became embroiled in the conflict, either voluntarily or involuntarily. By the end of the war, many blacks had been armed and had shown conspicuous gallantry during the course of the war. The decision not to issue medals to blacks after the war can be attributed to many factors which will probably never be understood completely. Whether the blacks served as scouts, messengers, watchmen in blockhouses, or auxiliaries, all these war activities were essential to the events that took place on the battlefield and all these services were necessary to support the war effort. While the contribtition made by the fallen soldiers will always be remembererl, many civilians, who did not actively participate in the war, were also deeply affected by it. One is reminded of the thousands of women and children, for example, who died in concentration camps. The Anglo-Boer War affected all the people of South Africa.

References

1. Nasson, Abraham Esau's War. p 94.

2. Nasson, Abraham Esau's War. p 94.

3. Labuschagne, 'The South African War: The role of agterryers

on commando, (UNISA paper, 1998) p 8.

4. Maphumulo, 'The Zulu in the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902'. (UNISA paper, 1998), p 4.

5. Maphumulo, 'The Zulu in the Anglo-Boer War', p 11.

6. Samuelson, Long, long ago, p 146.

7. Samuelson, Long, long ago, p 146.

8. Note on 'Holkranz massacre': this attack cannot be correctly

described as a massacre, which implies a slaughter of civilians, as it

was an attack against armed Boer commandos.

9. Maphumulo, 'The Zulu in the Anglo-Boer War', p 4.

10. Stowell Kessler 'Brutal truth behind "sacred history"

in The Star, 1 February 1999.

11. Lambert, 'Loyalty its own reward: the South African War

experience of Natal's "loyal" Africans, (UNISA Paper) p 15.

12. Nasson, Abraham Esau's War. p 185.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org