The South African

The South African

Huw M Jones

To the middle of September 1899, life went on with its customary normality for the population of Bremersdorp(1), headquarters of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek's administration in Swaziland. On Monday, 18 September, Special Commissioner J C Krogh laid the foundation stone of new government buildings. Consulted about the possibility of war, the British consul, Johannes Smuts, said it would not come for at least a year, but by the end of the month life in this small town had changed dramatically. From Pretoria came news of the imminence of war with Great Britain and instructions on how to deal with the situation. Families began to leave immediately and the school was the first government building to close. On Monday, 25 September, at a well-attended meeting in the courthouse, burghers heard the field cornet for Swaziland, Sgt J D Opperman of the Swaziland Police, explain the situation and the landdrost, P F de B Tenbergen, read out a letter in which Cmdt-Gen P J Joubert informed Ngwenyama Bhunu weMbandzeni that the white residents of the territory were being told to leave and that Swaziland was being left in his care. With neither question nor discussion, the meeting closed with the singing of the Volkslied. Two days later, Opperman issued rifles and ammunition to the burghers and the police practised with their rapid-firing Maxim.

Swaziland evacuated

On 2 October, the rumour spread that the administration

was being moved into a laager at Bell's Kop on the

western border and on the following day all official work

at the government offices was suspended. Krogh issued a

notice on 4 October which stated:(2)

Unconvinced by Smuts's equanimity or the orders of his London board to stay where he was, the manager of the gold mine at Pigg's Peak, E T McCarthy, bought canned provisions and all the canvas he could find in Barberton to tent his wagons. He hired donkeys to transport the wagons directly to Pigg's Peak rather than use the usual route for mine stores - by rail and wagon via Komatipoort. At the mine, McCarthy prepared twenty wagons for carrying provisions and the women and children of the mine's white employees, 400 trek oxen and 45 horses for the men to ride. The mine was closed overnight on 28 September, the staff paid off and a convoy of 74 people left for Delagoa Bay. To avoid being stopped and the wagons commandeered by the local police, McCarthy had secretly discussed his timings and route with the Pigg's Peak vrederechter, J M Ginjolen.(4) Instead of going northwards, McCarthy took his convoy down to Balekane where it would meet the old wagon road to the Bay. It took a week to reach the Lubombo range where representatives of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek and the Portuguese government were conferring on the undetermined boundary line. The ZAR's surveyor-general, G R von Wielligh, visited the camp and quietly warned McCarthy that he was still on land claimed by the ZAR and that it would be prudent to move into acknowledged Portuguese territory.

McCarthy had left Pigg's Peak just in time; soon after his departure, Boer officials arrested the mine's cyanide manager and two other miners and took them to Carolina, confiscating the remaining horses and guns.

Some Swazilanders had dual nationality. David Forbes Junior from Athole near Amsterdam was in the Swaziland lowveld looking after the coal mine on his family's property.(5) Opperman had already been there as he compiled a list of burghers available for service and refused to accept Forbes's assertion that he could not fight against his own people. Since Forbes had fought on commando against the Nzundza Ndzebele in 1884, Opperman put his name down. In early October, a burgher arrived with the order for Forbes to report to Bell's Kop with horse, saddle, bridle and thirty rounds of ammunition. Forbes led him to believe that once he had closed the mine down and paid off the men, he would ride to Bremersdorp. Having closed the mine, however, he told R P Miller (the brother of A M Miller) to drive his cattle towards the Portuguese border while he made a detour to avoid meeting the two policemen who were escorting the miners to the border. Forbes and his cattle evaded a police cordon and successfully reached Portuguese territory. He had earlier sent his brother James to Pisin (Pessene) in Mozambique with four wagon-loads of coal and orders not to return, and there the brothers established their headquarters.

Dress-rehearsal

Four and a half years had passed since Cmdt-Gen Joubert

had come to Swaziland with Vice-President N J Smit to

recognise Bhunu as ngwenyama and to establish an

administration without powers of incorporation. On their

visit to Nkanini on 15 March 1895, they had been

accompanied by Cmdt H P N Pretorius, commandant of the

Staatsartillerie, as well as a detachment of that corps with

several Maxims and a commando of some 1 000 burghers.

Joubert was well-acquainted with the country and

with the royal family and within two years he had been

forced to return to deal with a serious crisis. As the

indvuna of the Zombodze royal homestead and of

Ndhlovukazi Gwamile Mdluli (Labotsibeni), Mbhabha

Nsibandze had become indvunankhuluyesive, the senior

indvuna and a man of considerable influence, who

advocated solving the Swazi nation's problems with the ZAR

peacefully, particularly those concerning the imposition

of tax. This course the ngwenyama resented and on the

night of 9 April 1898 he engineered Nsibandze's death.

Krogh summoned Bhunu to Bremersdorp, a summons

which was initially resisted but met on 21 May. Tensions

were high as the ingwenyama rode into the town with

some 600 warriors in attendance and others escorting the

ndhlovukazi; and on the hills around the town another

2 000 were evident. Despite the ngwenyama's obvious

anger, nothing untoward happened and he retired to his

Mampondvweni homestead in the Mdzimba range with

some 1 000 warriors. The ZAR reacted to the tension by

increasing the size of the Swaziland police force from

89 to 120 under the command of Cmdt C Botha, entrenching

and fortifying the court-house and police buildings in

Bremersdorp, and mobilizing its forces.

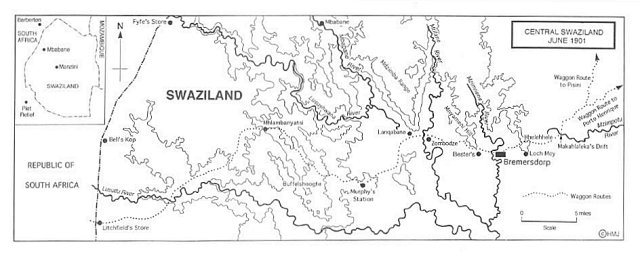

What followed was, in essence, a minor dress-rehearsal for the larger war two years later.(6) On 13 June detachments of the Pretoria Vrijwillige Infanterie Corps under Capt Melt Marais left Pretoria; they had been on standby since 10 May. With them came a detachment of the Staatsartillerie with four Maxim guns under Lt M S W du Toit, the only professional officer on what soon became known as the 'Swaziland Expedition'; with it also came a field ambulance company and field telegraph section. They had been joined by the Krugersdorp Vrijwillige Cavalerie Corps commanded by Cmdt B J Viljoen, with Capt G Figulus and Capt P F Maré. These units left the train at Belfast and moved through Bonnefoi to Carolina where they were joined by Cmdt D J Joubert of the Carolina Commando who took command. At Snaaksklip, 160 burghers of the Ermelo Vrijwilligers and Ermelo Commando joined the force to guide it into Swaziland. The force crossed the border on 22 June at Fyfe's Store and camped at Beacon Kop, before following the route taken by commandos in earlier years - on Mhlambanyatsi and down the Buffelshoogte - to reach Bremersdorp on Sunday evening, 26 June. Led by the Ermelo Vrijwilligers who acted as guides, the force of 600 men crossed the Mzimnene River and marched up to the Government Square. Meanwhile, 110 officers and men of the Johannesburg Vrijwillige Corps had left by train for Barberton where they went into camp near the gaol. Bhunu had been formally summoned to appear before a preliminary enquiry into Nsibandze's murder on 5 July and Cmdt-Gen Joubert had arrived on the previous day with the newly appointed commandant of the Staatsartillerie, S P L Trichardt. At 1100, the court assembled, but waited in vain; Bhunu had fled to the British magistrate at Ngwavuma. The force initially camped on Church Square where a fort was built; the Staatsartillerie and the Pretoria cavalry built and occupied another large fort on the ridge west of the town. Eventually the ngwenyama returned to Bremersdorp where he faced an enquiry and, after extensive consultations between the British government and that of the ZAR, he was fined £500 with £1 146 in costs.

The force did no more than demonstrate, the only action being a brawl in the International Hotel between men from the Pretoria cavalry and infantry units which became a dispute between Hollanders and Afrikaners; De Korte put the hotel out of bounds. The Pretoria infantry and Krugersdorp units left for Komatipoort Station through Buckham's (Croydon) in the lowveld in early September before the enquiry started, followed a month later by the Pretoria Vrijwillige Infanterie Cavalerie Corps once the ngwenyama had been allowed to return to his homestead. Some lessons had been learned while others were ignored. Instead of going on to Machadodorp, where wagons had been commandeered, the force had left the train at Belfast. The Machadodorp drivers had refused to go there and Marais had been forced to halt for two days before he had been able to obtain seven wagons, eventually increasing the number to 23. The wagons had severely slowed the force as it moved across the highveld and down the rugged terrain into Swaziland, a problem which would later face all Boer commandos in the early stages of the Anglo-Boer War. On the march, bread had been scarce and the men had had a hard time, but once in Bremersdorp rations had been no problem. Soon after the arrival of the force, a false alarm at night had provoked a very fast response, with all posts being manned, lights out and tents flattened in two minutes. It had also been a useful exercise for the Swazieland Police who were able to mobilize a commando very quickly in September/October 1899.

Early days of the war

With the outbreak of war in October 1 899, those who had

co-operated well a year earlier, formed different

affiliations. The sheriff of the court, who had delivered the

summons to the ngwenyama in tense circumstances, J H

Howe, unofficially supported by L F Townsend of the

Staatsartillerie, found himself commandeered as a burgher

for active service despite his Natal origins. Taken to

Bell's Kop Laager, he escaped and reached Lourenço

Marques. F A Goulding, looking after the mine property

as Forbes' Reef, was arrested and confined in Pretoria

before arriving in Lourenço Marques on 19 November.

On 7 November, C M Meintjies, the public prosecutor,

and five burghers arrived at J J Bennett's store near the

Mtilane River with two wagons and ordered the Bennett

family to get into the wagons and go into laager at Bell's

Kop.(7) Mrs Bennett and the children escaped into the bush

whilst Bennett himself scrambled up the nearby Mdzimba

range above the Zombodze magistracy and police post. The

ndhlovukazi sent a messenger to bring the family

to the safety of the roval homestead at Zombodze

whilst Bennett wandered in the hills. He was arrested at

H W Kelly's store three days later by two armed burghers

and taken to Zombodze police post. From there he was

taken to Mbabane and Bell's Kop where he was interrogated

by N J M Vermaak, senior vrederechter in Swaziland,

with C S Koevort, Krogh's secretary, interpreting

(Tenbergen was then in charge of the laager, Krogh having

gone to Piet Retief). Among those officially allowed

to stay in Swaziland was V M Stewart, manager in

Bremersdorp of a branch of the trading company Schwab

& Co; he had been appointed to act as magistrate and

report on the situation in Swaziland to the Boer authorities.

Stewart continued to trade, railing his goods from

Lourenço Marques to Komatipoort from where they

were taken by wagon under an escort of the Republic's

police to Bremersdorp. At Usutu Mission the Rev and

Mrs Swinnerton left a Swazi catechist, F Dlamini, and his

wife in charge and tried to reach Volksrust by wagon, but

the course of the war and Mrs Swinnerton's illness forced

them to take refuge at another Anglican mission, Ndhlozana,

in the Little Free State close to the Swaziland border.

Here the country was also in turmoil, but the resident

missionaries, the Rev and Mrs W M Mercer and their

family, with Brother S T Harp, had stocked up with

canned goods and were determined to stay. On 5 October

a burgher had commandeered three Swazi men and three

Swazi boys from the mission as drivers and voorlopers in

addition to eight oxen.(8) From the Scandinavian Alliance

Mission at Bulungu the Rev and Mrs W F Dawson

trekked south sending a message for their colleague,

Miss Malla Moe, at Bethel Mission Station near Sihlutse

to join them in the lowveld. The message never arrived

and the Dawsons carried on into Zululand.(9) At Henwood's

store near Bethel, J C Henwood was ordered to leave,

but persuaded Moe to look after his ailing father at

his store. Shortly afterwards a Boer commando arrived

and looted the store, taking £1 400 of Henwood's money

in gold sovereigns from the safe. The old man

remonstrated with the Boers to no avail and collapsed, dying

from a stroke induced by the exertion.(10) Moe returned to

the mission and continued to preach in the surrounding

area until she was evicted by the Boers early in 1900 and

sent to live with T Klopper on the farm Excelsior near

Piet Retief. She later returned with permission to live at

the mission. This was only one instance of widespread

looting throughout Swaziland. Emmett later wrote that

'We could not take our furniture with us and we lost the

lot - mostly looted by invalid or sickly burghers who

could not go to the front and who could show doctor's

certificates as to their wives' "interesting conditions!"'

On the southern Lubombo, the Republic's special representative, H F von Oordt, had been ordered to join the Piet Retief Commando so he was not there when the Swaziland Commando led by Cmdt C Botha attacked the small British police post at Kwaliweni on 28 October. The commando was accompanied by J J Ferreira, vrederechter at Mkwakweni in southern Swaziland. The resident magistrate at Ubombo had been told by Chief Sambane Nyawo that Ngwenyama Bhunu had sent word that he was to be attacked by two Boer commandos and an African commando.(11) The commando of some 200 burghers did split in two, one party climbing the western scarp of the Lubombo to attack Kwaliweni. The post comprised two white troopers with a sergeant and seventeen men of the Zululand Police, all of whom prudently withdrew to the magistracy at Ngwavuma. Having burned the post and L C von Wissell's store, the commando moved to Ngwavuma which had a small fort. The magistrate, one of the ten whites with 25 Zululand Police, ordered the evacuation of the village to Nongoma, successfully evading the other half of the commando waiting in ambush on the road down the eastern slopes. The commando looted the store, also owned by Van Wissell, and burned every building except the small hospital and doctor's house.

The Swazi independent again

In his letter to the ngwenyama, Joubert had written that

the Swazi must remain quiet and calm and not become

involved in the war and that C Botha and M J J (Thuys)

Grobelaar would liaise between him and the governments.

Grobelaar had acted as personal liaison between President

S J P Kruger and the ngwenyama for several

years, paying him his monthly stipend of £l 000. Botha

was clearly busy elsewhere and so Grobelaar was accompanied

by J G Dingley, a farmer from Dingleside in New

Scotland where he had been among the first settlers and

had been granted citizenship of the Republic. They went

to see how the Swazi were disposed towards the Boer

forces and whether any British troops were moving through

the territory. The ndhlovukazi had complained

about armed burghers in Swaziland and Krogh, having

warned everyone that it was at their own risk if they did

so, several times turned burghers with their families and

stock back from the border. The government of the

Republic was uneasy about the situation in Swaziland. On

the withdrawal of the Republic's administration, the

ngwenyama realized that there were now no restraining

influences on his behaviour and alcoholic excess induced

serious illness. To combat this, several people were

killed at Mampondvweni including the venerable and

sage diplomat, Mnkonkoni Kunene, and one of his

wives, together with a wife of Matsofeni Mdluli and two

of her maids. Settling old scores, Bhunu had a witness

who had testified against him at the 1898 enquiry, Nyangana,

and several of his people, killed in the Mbabane area.

News quickly reached the battlefields around

Ladysmith where Cmdt D J Schoeman, heading the

Lydenburg Commando whose burghers had close links

with Swaziland, wanted to know the situation. He was

assured from Cmdt-Gen Joubert's laager that the Swazi

were well disposed towards the Republic. Cmdt H N F

Grobler and Field Cornet H F Prinsloo from Carolina,

who had been at Bell's Kop, were expected at the laager

on 10 November to report on the situation. Krogh sent

two African spies as far as the Lubombo range to assess

the situation and they reported that the murders resulted

from Bhunu's fear that he had been bewitched.(12) Even

Bhunu's close friend, Jilo kaMancibane Dlamini, had not

escaped notice and been warned to escape to the Republic,

but he left Mampondvweni for Zombodze where he

committed suicide by shooting himself. Krogh reported

to the government that the Swazi were peacefully tilling

their land and that Grobelaar and Botha would visit the

ngwenyama to discuss the murders. On the night of 10

December 1899, however, Bhunu died at Zombodze and

Stewart, that 'credible and trustworthy person', reported

the matter to Krogh in Amsterdam immediately. The

ndhlovukazi became queen-regent and immediately set

about eliminating those close to the late ngwenyama,

such as Mnt Zibokwane Dlamini who had been his

'guardian' and senior adviser. Groups from the Swazi

regiments roamed through the country and even threatened

the south-western border where Boer women and children

left on farms fled to Piet Retief for satety.(13) The

Republic, however, felt sufficiently secure on its eastern

border to send the fully supplied and equipped Swaziland

Commando southwards in January 1900 to join the fighting

along the upper Thukela River. For many years,

farmers from the highveld, and particularly from the

Wakkerstroom and Piet Retief districts, had trekked

sheep into Swaziland for winter grazing. On 24 January

1900, the Mercers at Ndhlozana were told to have no

communication with Swaziland and, with the onset of

winter, the state secretary advised the landdrost of Piet

Retief to tell burghers that trekking was undesirable.

That advice, given on 18 April, was followed the next

day by a notice that trekking was now forbidden.(14)

The Komatipoort Railway Bridge

The British were also concerned about Swaziland. From

the outset, they had worried about war material passing

through Lourenço Marques to Komatipoort and of

Swaziland being used as a corridor to smuggle supplies to

the ZAR. A prominent financier in Johannesburg with H

Eckstein & Co, S Evans, was sent by the high commissioner,

Lord Milner, to Lourenço Marques in late December

to assess the situation and, in the course of his

visit, he went to Pisini to meet Forbes. In January 1900,

R D Casement, former consul at Lourenço Marques,

returned to examine the situation. Both reports focussed on

the possibility of destroying the railway bridge at

Komatipoort to block the railway; in addition, Evans

mentioned the possibility of creating a 'Forbes Swaziland

Corps', established on the Lubombo range to harass

the railway and any burghers in Swaziland. Infructuous

attempts to destroy this bridge by a squadron of Strathcona's

Horse guided by Forbes from Kosi Bay, as well as a

small, independent force of Colonial scouts under Lt

Baron F C L von Steinaccker, have been previously

documented in this journal and need only be sketched in

here.(15)

Lourenço Marques and its connections with Swaziland had been important to the British from the outset of the war. Only some 45 km to the west, the Lubombo range had for some twenty years been a locus for white residents who, for various reasons, preferred to live on the fringe of society. Most of this small group had established themselves east of Siteki close to the then undefined border and become involved in transport riding between Porto Henrique, the highest tidal and navigable point on the Tembe River from Delagoa Bay, and the burgeoning gold mines of Swaziland and the agricultural potential of New Scotland. More recently, others had settled further north at Nomahasha where the Portuguese were interested in establishing a settlement. Most of the British residents in Swaziland had left for the Lubombo range and the information which they could provide was of immediate interest to the British consul, A C Ross. He was supported by the appointment of R Diespecker from Field Intelligence in Cape Town. Before the war, Diespecker had been general manager of the Selati Railway. An intelligence network involving Lubombo residents was established, initially aimed at detecting arms smugglers. Forbes was one of the first to call on 23 November to report that the Portuguese had already taken advantage of the situation to collect taxes and exercise control over land on the Lubombo that had not been recognized as Portuguese. On 19 December, T B Rathbone, a long standing Swaziland resident and lately Bhunu's principal white adviser, called at the consulate to say that the ngwenyama had died. This was one route by which the British maintained communications with the Swazi.

Swazi diplomacy

After Bhunu's death, the Swazi royal house was primarily

concerned with the rituals of mourning and the question

of succession. The queen-regent made no obvious moves to

favour either side in the war, but may have been influenced

towards the British by Mrs Bennett, acting as her secretary,

and by the possibility that the Republic's officials might

endorse a candidate not to her liking. Memezi waMswati had

supported his elder brother, Mbilini, in the fighting

against the British during the Anglo-Zulu War and afterwards

became closely associated with J J Ferreira, native

commissioner in the Piet Retief district and from 1895

vrederechter at Mkwakweni in southern

Swaziland. After the death of Ngwenyama Mbandzeni

weMswati in 1889, Memezi had taken one ofhis wives,

Ncenekile Simelane, as an ngena'd wife. Her son,

Masumphe, was Mbandzeni's choice to succeed him, but

because of his mother's violent temper, the family council

had not endorsed him and chose Bhunu. As early as

1896, it was known that Masumphe was being educated

in Pretoria ready to succeed once the Republic managed

to oust Bhunu. Now that Bhunu was dead, the queen-regent

must have considered the possibility of intervention,

but the Republic was much too involved with the

prosecution of the war. On 4 February 1900, Krogh arrived at

Zombodze and presented the queen-regent with ten head

of cattle; the gift was refused, but the cattle were still in

the royal sibaya five months later. As ndhlovukazi, the

queen-regent had favoured her own son, Malunge, and

with the sudden death of the 22 year old ngwenyama the

succession was again wide open.(16) Watching from Zululand,

CR Saunders, civil commissioner and chief magistrate,

reported on 22 March that affairs in Swaziland were

settling down; the queen-regent had summoned the chiefs

to assemble,(17) but one close observer of the political

scene, J Gama, anticipated serious dispute over the

succession.(18) July was declared to be the official month of

mourning.

The queen-regent opened up a channel of communication with the British through the magistrate at Ngwavuma once he returned in May 1900, sending messengers to say that if she needed British protection she would flee to his district. With some humour she reported that the Boers had painted their faces red to disguise themselves (as British) and thus force the Swazi to fight alongside them. The Boers had four laagers in what she regarded as the Swazi country - one at Bell's Kop, one at Moodies and two near Mahamba. These messages were passed through Saunders and the government of Natal to the high commissioner in Cape Town. Here J Smuts, erstwhile consul, had joined Milner's staff preparing messages for his approval and despatch via the messengers waiting at Ngwavuma. In late June the queen-regent asked why, if the Boers were beaten, the British did not occupy her country? This was a foreign policy line taken by the Swazi for many years - asserting independence, but hesitant without the support of either the Republic or Britain. The queen-regent revealed her anxieties about Memezi by asking whether she could take steps to reclaim cattle taken by Memezi from Bhunu when he had fled to Ngwavuma in 1898. One important messenger with an appropriate escort was Lomvazi waMbandzeni, the queen-regent's fourth child by Mbandzeni and a natural younger brother of Bhunu. He arrived at Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo's Usutu homestead in May 1900 to report his father's death and Dinuzulu formally reported his arrival to J Y Gibson, the magistrate at Nongoma. Gibson met him on 13 July and ascertained that only Zibokwane had been killed expressly on the queen-regent's orders since she had blamed him for her son's death. Through the Ngwavuma messengers the queen-regent was told about the progress of the war and that the Swazi were not forgotten - they could 'rely on British representatives returning to the country at an early date'. Drafted by Smuts, the reply showed that he wanted to replace Krogh's authority with his own, backed by the British government. But the tides of war had distorted lines of communication and boundaries of responsibility between the military and civil powers aud it would not be easy for him to further his ambitions.

The Republic was not alone in its concern over the murders in Swaziland. Sir F A Bartlett, a grandiloquent protagonist of Britain's important imperial role as staunch defender of Swazi interests against those of the Republic, persuaded Field Marshal Lord Roberts to sanction a secret journey to visit the queen-regent. With a Johannesburg journalist of similar views, H R Abercrombie, Bartlett arrived in Lourenço Marques ostensibly on a hunting expedition and took the train on 25 March to Forbes's camp at Pisini. From there, guided by Forbes aud A K Brooks, they rode across the Lubombo to reach Zombobze where they found Rathbone. Bartlett's aims were firstly to persuade the queen-regent to prevent Boer forces from occupying the mountainous areas of the territory, secondly to persuade her to sign an appeal for British protection aud thirdly to adjure her against indiscriminate murders. The petition was duly signed at Nomahasha, and Bartlett and Abercrombie returned to the consulate on 3 April. Forbes had used the occasion to impress his ideas on Bartlett who duly told Ross that a force of 500 men was needed in Swaziland to deny the Mdzimba range to the Boers, counter their influence and harass the railway line. Bartlett then went off to tell the same to Lord Roberts in Bloemfontein and to reinforce the idea of destroying the Komatipoort bridge.

The Komatipoort bridge again

Forbes's next involvement was with the attempt to

destroy the Komatipoort bridge and with the landing at

Kosi Bay of a squadron of Strathcona's Horse, commanded

by Lt-Col S B Steele, which, guided by Forbes,

would proceed north along the Lubombo, avoiding Portuguese

territory, and strike at the railway line. While

Forbes waited in the breakers on 4 June to collect the

troops, he received a laconic signal from a small coastal

cruiser, HMS Widgeon, waiting offshore, that the

operation had been cancelled.Two days earlier Rear-Admiral

Sir R H Harris commander-in-chief of the Good Hope,

on his flagship HMS Doris with HMS Monarch and

the Widgeon, was waiting off the bay for the transport

Columbian and Wakool with the expeditionary force.

On Sunday 3 June although the weather was fair and the sea

calm, Harris cancelled the landing and autorized the

two transports to proceed to Durban for orders. He had

told Steele the night before of the despatch from the

consul-general in Lourenço Marques saying that the Boers

knew the plans, had reinforced the Komatipoort garrison

and were sending a large force to impede the advance of

the expedition. While the despatch had been addressed to

Forbes, Harris misinterpreted the information without

waiting to consult him and Steele decided that it was

impossible to carry out the object of the expedition.

Ordered to Eshowe, Forbes found that Strathcona's Horse had been sent on to Standerton and so he returned to Mozambique. Ever alert to his major ambition to see the construction of a railway to export coal from his lowveld holdings, Forbes wrote to Evans, now on the staff of the civil commissioner in Johannesburg, about the failed expedition which had, however, allowed a look at the country. He saw the possibility of establishing a port for shipping coal and a railway. Was Evans interested? Evans passed the letter to J P Fitzpatrick with the comment that 'Tongaland was not under the Imperial government'. It added to the correspondence which the high commissioner was generating on the same subject,(19) but Milner had already received a letter from Forbes, written in Durban whilst awaiting passage to Lourenço Marques, which promoted the idea of a port and railway to exploit his lowveld coal as well as that found in New Scotland.(29)

On their way south, Forbes had come across the remains of a temporary camp where an old copy of the Natal Mercury and a tin of Oxford sausages had been found. The camp was that of Von Steinaecker and his group of Colonial scouts who had already made contact with L C von Wissell at Mtini's Drift on the Phongola River and J A Major at Phalata farm on the Portuguese border. (21) When the war had started, Major had moved his cattle to a camp across the border to prevent them from being commandeered and did intelligence work for the British consul at Lourenço Marques; he became disillusioned when accused of looting cattle taken by Boer forces from Natal. In a letter to a relative, Major described how he had left because the 'man-in-charge' was incompetent.(22) The war provided plenty of opportunities for settling old scores and intelligence reports need careful interpretation. As one example, a secret report from the consul-general in Lourenço Marques to the governor of Natal averred on good authority that 'A man named Major who is now in Swaziland, somewhere between the headwaters of the Umbumbane and Tembe (close to the Portuguese frontier) has looted a lot of Boer cattle, and it is quite possible that he will be driving them for protection into Zululand. Two other British subjects named Oswin and Patterson, are trying to play the same game of cattle lifting from the Boers .. I believe the men named before are right enough, but one named Dupont, on the same business, is a [bad lot?].(23) There is no evidence to suggest that this report was accurate.

After becoming involved with Major in a fracas involving two groups of Swazi, taking advantage of the wider situation to repay old scores, Von Steinaecker reached Nomahasha in early June where he established good relations with Mbudula Mahlalela, an important chief with a considerable degree of independence from the Swazi royal house. The Komatipoort bridge was too well guarded for Von Steinaecker's small group and so the unguarded bridge at Malelane was blown up on 16 June, halting railway traffic for two weeks. The British presence on the Lubombo attracted more Boer forces to the area to meet what was rumoured to be a force of some 300 men. Cmdt G M J van Dam of the Johannesburg Police was ordered to patrol the railway line through the lowveld and, early in July, with a party of 4O burghers, he climbed the Lubombo to Mahlalela's homestead on Mpundvwini Mountain. Accompanied only by two others, since he thought himself safe on what he believed was the Republic's territory, Van Dam was ambushed and taken prisoner by Von Steinaecker's men.

The success of this small group encouraged Lord Roberts to sanction an increase and the consul-general in Lourenço Marques recruited local residents and financed and provisioned their activities. Visiting Natal in August, Von Steinaecker made arrangements for more recruits, supplies, personal promotion to the rank of major, and the creation of a unit to be called Steinaecker's Horse. Returning to Kosi Bay on the Widgeon, he was met by Forbes with three wagons and was back in his camp on the Lubombo south of Nomahasha by 17 September, a week before Lt-Gen R Pole-Carew's 11th Infantry Division spear-headed the British advance eastwards along the railway and entered Komatipoort unopposed on 24 September. Most of the 3 000 burghers trapped at the border crossed into Mozambique with Cmdt J J Pieuaar, but a column led by the Rev M P A Coetzee successfully moved northwards through the lowveld towards the Lydenburg area. Von Steinaecker made Komatipoort his base, but maintained a camp on the Lubombo with its piquet post on the scarp edge commanding extensive views across the lowveld, a place still known to the Swazi as Piketesi. As Lt-Gen J D P French's cavalry division swept through the Barberton area, burghers fled into Swaziland where they were harassed by the Swazi who took their cattle and their rifles.(24)

The future of Swaziland considered

At Government House in Cape Town, the future of

Swaziland was being considered even before Pretoria fell.

Here, Johannes Smuts moved to play the leading role in

bringing Swaziland into the British fold. He was a Cape

Afrikaner who had been private secretary to Lord Loch

when high commissioner; for him it was a matter of regret

that he was not 'home born' and his official life was

played against a 'more British than the British' backdrop.

On his own initiative, he prepared a memorandum on 28

May on the future administration of Swaziland, but Milner

deferred consideration.(25) As British forces advanced

eastwards towards Komatipoort early in September,

plans were hatched for Smuts to visit Swaziland; he was

to be accompanied from Cape Town by AM Miller as his

unpaid secretary, ostensibly to provide information on

the Swazi and their language. Here again, however,

commercial interests were not allowed to be forgotten in the

prosecution of the war. Miller was the Swaziland manager

of the Swaziland Corporation Limited and had recently

returned from Britain where he had prepared a

memorandum on the corporation's assets and the valuable

development opportunities which the territory offered.

On 8 May he had addressed this theme to a wider

audience at a meeting of the Royal Colonial Institute

chaired by Sir Sidney Shippard. Also present was Bartlett

who, having just returned to London, missed the speech

and some of the discussion, but was able to assure the

meeting that stories of the state of anarchy in the

territory were untrue.(26) Forbes was summoned from Pisini

to join Smuts and Miller in Pretoria where they arrived

on Monday 10 September and met Lt-Col H V Cowan,

Lord Roberts's military secretary. Briefing papers on

Swaziland were prepared for the Director of Military

Intelligence. On 26 September, doubtlessly prompted by

Smuts, Milner cabled Roberts that he did not want to

leave Swaziland without white influence for too long

and, if Roberts agreed, wished to send Smuts to Barberton

to try to establish communications with the Swazi from

there.(27) Roberts replied that he had no intention of

sending any force there at present and Smuts was in

agreement that he could not enter the country unsupported.

From Pretoria. Smuts advised Milner on 28 September

that he was leaving for Barberton that day with Miller

and Forbes and proposed another career move, to which

Milner responded that he approved 'his being styled

Resident Commissioner for the present, without prejudice to

the question of his ultimate position.'(28)

Swaziland Communications

Independently of the queen-regent, the most powerful

man in southern Swaziland, Ndabazezwe waTsekwane

Dlamini, had been providing the magistrate at Ngwavuma

with important information about Boer movements.

Another important Swazi informant was Tshingana kaTole

who had served as one of J J Ferreira's 'police', but

had become disenchanted when the vrederechter had

ruled against him in a dispute concerning cattle; Tshingana

supplied the British with details of the movements of

Ferreira and his agents and also of M S Thring.(30) For

these services, the Natal cabinet rewarded Ndabazezwe

with four heifers and Tshingana with two.(31)

With the fall of Komatipoort in September 1900, Swaziland provided the only effective route for Boer communications with G Pott, Netherlands consul in Lourenço Marques. In November 1900, Asst Cmdt-Gen C Botha, then in Piet Retief, asked A L Kuit, a postal official, to take despatches to Pott and return with gold for the Boer forces. Kuit was accompanied by the brothers Louis and Izak van Rooyen and first had to obtain a pass to go through Swaziland from Krogh at Bell's Kop. Here they found another group comprising Meintjies, H Viljoen and J Duprat also bound for Lourenço Marques on Krogh's instructions. This group arrived in Bremersdorp on 13 November and left the next day, followed a day later by Kuit's group. V M Stewart told them that Steinaeeker's Horse was patrolling the Lubombo and coming as far as Bremersdorp. Kuit and the Van Rooyen brothers left that evening, pretending to return to the Republic but, once clear of the village, turned around to cross the lowveld. On 16 November they arrived at the homestead of Jozana Maziya, another Mahlalela chief then living where the village of Siteki is today. He was thought to be sympathetic to the Republic and to Krogh in particular, but Maziya ordered them to move on. On the return journey, Kuit found that Maziya had told a detachment of Steinaecker's Horse of his visit and he and his companions had a difficult time eluding the British forces. They passed close to Bremersdorp and came to the store at Murphy's Station (now Malkerns) where M K Stewart was astonished to see them, having been told by his brother that they had returned to the Republic. When he saw the poor condition of their horses, Stewart believed their story and provided them with the little that remained in his store. Presumably for this exploit, Kuit was the only person who was not a commissioned officer of the Boer forces to be awarded the Dekoratie Vir Trouwe Dienst, a medal awarded to officers for distinguished service.(32)

Also making the journey across Swaziland from Lourenço Marques was J Forbes, who went to see his family at Athole near Amsterdam. On 16 November he returned with a letter from his father, D Forbes Senior, that a commando of 500 burghers with ten guns had been there on 10 November and that burghers were being commandeered to augment it for an attack on Vryheid. Having no confirmation of this, the British took no action and Vryheid was attacked on 11 December.(33)

In addition to her link with the British through Ngwavuma, the queen-regent opened up communications with Brig-Gen T E Stephenson who had taken over command in Barberton. In response to letters from Roberts and Smuts, she reported that she was doing her best to drive Boers out of her country. She had ordered Mtshakela (J J Ferreira) out of the country, but he had responded by bringing in armed burghers and Africans, among whom was Memezi. Meintjies had arrived in Bremersdorp on 13 November, but had been ordered away. Since then, three armed burghers (Kuit and the Van Rooyen brothers) had been in Bremersdorp. Ferreira had sent her three goats which she had returned; Grobelaar, however, had sent ten head of cattle which she would keep until sile heard from Smuts what should be done about them. Mrs Bennett added a personal note to Roberts, asking for 'pecuniary assistance' and permission for her husband to come and stay in Swaziland. Finally she begged Roberts to 'warn the Queen against showing any letters from the British to others than herself as there are educated natives and being favourable to Boers probably take copies for them'.(34)

On 29 November 1900, Kitchener succeeded Roberts as commander-in-chief and on 20 December Smuts addressed Kitchener's military secretary, Capt W N Congreve, VC. Explaining his background and noting that he had been sent to Pretoria by Milner 'with a view to returning to Swaziland as resident commissioner', Smuts referred to the fact that a detachment of Steinaecker's Horse had been in Bremersdorp on 8 December and that 'if I had known that this visit was contemplated, I would have pointed out that the High Commissioner's wish was that when British officials went into Swaziland they remain there and that I should be the person to take charge of the territory'. A patrol led by Lt C S Carmichael had visited Bremersdorp and taken eight people prisoner. The brothers V M and B B Stewart, who had previously served with the so-called 'English Police' prior to the Republic's administration, were among them. Carmichael had ordered V M Stewart's wagon to be burned and had taken his two horses. Left behind to continue trading were a German and another British national, H R Middleton. Smuts learned of the patrol from V M Stewart, then a prisoner in Pretoria, who had stayed in Swaziland on the Republic's authority to trade aud supply information on British movements. With the tide of war clearly swinging in Britain's favour, Stewart was obviously anxious to ingratiate himself with the British authorities. During an interview with Kitchener, Smuts was shown the letter from Mrs Bennett, which he did not think merited a reply, but Kitchener disagreed, saying that it would be good to send a letter which would be read by the Boers.(35) So Kitchener thanked the queen-regent for her letter, introduced himself as Roberts's successor and asked her to keep him supplied with news of Swaziland. Admonishing the Swazi to take no part in the war, he said that unless Boer forces entered Swaziland in large numbers, he would not send British troops into the country. Finally, he told the queen-regent that, as the British Crown had annexed the Transvaal, Her Majesty the Queen 'now stands in the same position to the Swazis as the Transvaal did before the war.'

A letter from Forbes, then back in Lourenço Marques,

arrived after the interview, adding to Smuts's discomfort.

The success and formal establishment of Steinaecker's

Horse irked Forbes. He complained that their successes

were exaggerated and that many of their African scouts

were armed and had been sent on their own to seize cattle

from whites. Forbes maintained that some 300 Africaus

were employed at salaries of between £3- 10-0 and £6 per

mouth which, presumably because he regarded them as

high, would harm Swaziland. In a diatribe against the

corps, he wrote that:

No judge of character himself, Smuts must have been galled to read that 'Sandy McCorkindale seems to have charge of Swaziland' and that Rathbone was used to pass messages to the queen-regent. Forbes was angry because his father's message about the impending attack on Vryheid had been dismissed and he concluded: 'It is very disheartening to have anything to do with the military. Adventurers well versed in egotism are trusted by them, but honest men who are known to be of some social standing are invariably looked on with distrust, but certainly always with indifference'.(37) Forbes had been in Komatipoort when Lt B P A Geldenhoys had arrived there as a prisoner. Geldenhuys, a member of the Transvaal-Verkenningskorps, had been captured in late October 1900 at the Nkhomati River on the Swaziland border by a party of what he described as 'National Scouts' with armed African allies. Taken on foot to A (Sandy) McCor- kindale's farm at Ndzingeni east of Pigg's Peak, he had escaped, only to be captured by a party of Swazi and then marched on McCorkindale's orders to the British base at Komatipoort. Geldenhuys was familiar with both the country and his captors since he had been a clerk collecting the personal taxes introduced in Swaziland in l898.(38)

Thinking that Forbes's letter would reinforce his

own derogatory views of Steinaecker's Horse, Smuts

forwarded it to Congreve on 29 December with the

observation that the 'raid' on Bremersdorp was bad, but the

'arming of natives for fighting and looting is far worse'.

Smuts wanted Kitchener to read the letter and this was

acknowledged in Congreve's very brief reply Forbes had

had his chance to do what Von Steinaecker was doing but

had delayed so long that the work had been given to Von

Steinaecker instead. 'No-one', added Congreve, 'thinks

S all angel, but he has his uses and Forbes being jealous

must be taken at a discount'.(39) Smuts persisted in his

criticisms and on 4 January 1901 sent a despatch to Milner;

he failed to see what good the December patrol could

have done, suggesting that it might provoke Boer reprisals

on the British citizens left in the territory. The Swazi,

he thought, would regard it 'as nothing more than a raid

for plunder'. The Forbes letter and Congreve's response

to it accompanied the despatch with the comment that 'it

appears to me that the military don't welcome or care to

accept information from civil sources'. 'As', he concluded,

'I understand that your Excellency does not wish action

taken in Swazieland [sic] until an official is sent in

to establish an administration, and as the Commander-in-Chief

desires to avoid making Swazieland [sic] a scene of

military operations, I hope the actions of Steinaecker's

Horse in that country may he kept under control.'(40)

Milner responded by telegraphing Kitchener that, as he had

heard that Steinaecker's Horse was raiding in Swaziland

and carrying off Boers, would it not be better to leave

Swaziland completely alone since sporadic incursions may

lead to 'native risings' and 'may excite Boer reprisals'?

He would be inclined to treat Swaziland as friendly

but neutral and asked for Kitchener's views.(41) The

commander-in-chief's reply was terse:(42)

'I think matter exaggerated. Forbes and Smuts not

very reliable when relating to what they hear from

Swaziland. Steinaecker will not make raids into

Swaziland or disturb there, but I must stop

communication with coast. As far as I know Steinaecker's

men have only once been in Swaziland and

I have told him to be most careful. Absolute

prohibition to enter Swaziland would be a great

assistance to Boers getting ammunition. Who is

your informant?'

As Milner appeared his only sympathetic contact, Smuts later added what he considered even more shocking detail to his earlier despatch. From the Stewarts, then paroled as prisoners-of-war, he had learned that armed Africans had accompanied the December patrol to Bremersdorp and that in camp on the Lubombo they were used to escort white prisoners to bathe and to the latrines.(43)

Incursions by British troops

Preparatory to a massive sweep through the eastern

Transvaal towards the Swaziland border, French ordered

a detachment of the Imperial Light Horse under A

Wools-Sampson to clear burghers from the area around

the mining camp in the mountains behind Barberton,

called French Bob's, and on 21 December 1900 he

reported that the burghers had retired through Swaziland.(44)

On 26 December he telegraphed that he was sending an

officer to meet tindvuna from Swaziland at Devil's

Bridge (Bulembu) to impress on them the necessity of

preventing any violation of their country by the Boers.(45)

Eight columns left their start-line on 28 January 1901,

moving eastwards. Living conditions in the south-eastern

Transvaal, already precarious, had deteriorated. By 8

January 1901 there was no bread, coffee, sugar, light,

salt, soap or tinned goods at Ndhlozana Mission.(46) Smuts

met another prisoner-of-war in Pretoria at this time, C B

de Villiers, whom he had known in Bremersdorp before

the war. De Villiers was from Piet Retief and reported

that the burghers in that area had moved with most of

their stock further east into the Mkwakweni hills north of

the Phongolo River. They were very impoverished with

no proper clothing, only meat and mealies but no salt,

and the women and children in particular were suffering.(47)

French's objective was to advance to a line from

Piet Retief northwards through Amsterdam and force the

commandos in the area either to surrender or to move

into Swaziland.(47) Maj-Gen H L Smith-Dorrien's column,

one of the eight involved in this sweep, was attacked in

the very early morning of 6 February near Lake Chrissie

(Chrissiesmeer) by some 2 000 burghers from the Middelburg,

Ermelo and Krugersdorp commandos. Absorbing severe casualties,

the attack was repulsed and the column bivouacked there

until 9 February when it pushed inexorably towards Amsterdam

and the Swaziland border. From then on, the weather deteriorated

rapidly, torrential rains swelled the rivers, and the heavy

ground slowed the wagons, many of which had to be

man-handled out of the mud.(49) But the retiring Boers

were also handicapped and the British mounted infantry

were successful on 9 February in taking 50 wagons as

well as some 4 000 head of cattle and 4 000 sheep. In

addition, huge herds of cattle and sheep were taken from the

farms and they posed an immediate problem. Volunteers

were called up to slaughter the sheep, soldiers being

awarded one penny for each sheep killed. At Warburton

on 1 February all available soldiers were called out and

with their bayonets and knives killed some 15 000 sheep

before moving on at 08.30. 'Awful sight', as one officer

noted.(50) That day, operating on the Swaziland border, the

mounted infantry took 19 wagons, 3 400 head of cattle

and 5 000 more sheep.(51) Many refugee Boer families with

the convoys were brought in to the British camp and the

whole area was cleared of white inhabitants, British and

Boers alike, most of the latter finding their way to the

concentration refugee camp at Volksrust.

Swazi deputation to the British, led by Mnt Logcogco (centre)

at Litchfield's Store, 19 February 1901. (Photo by Lt M Riall,

West Yorkshire Regiment, courtesy of Nicholas Riall)

With heavy rain continuing to fall, four companies of the 2nd Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire) Regiment left their camp at Tweepoort, on 19 February 1901 for Litchfield's Store. Ihere, Maj H E Watts had a discussion with a Swazi chief named as Gondo (most probably Mnt Logcogco, the senior prince and regent) and handed over a gift from Smith-Dorrien of 1000 sheep and 50 black oxen from the captured herds.(54) From there that day, Lt-Col D Mackenzie took the Imperial Light Horse some ten kilometres into Swaziland down the Ngwempisi River and the Suffolk Regiment, based at the store, also went into Swaziland. Together the columns killed one and wounded two burghers, took 31 prisoners as well as 2 700 cattle, 5 000 sheep, 60 horses (half of them saddled), 15 mules and three wagons complete with ox spans. On this occasion, the Swazi joined the British troops, firing at the Boers, carrying off their rifles and cattle(55) and destroying their wagons. Heavy rains continued to slow the British advance and seriously delay the arrival of food convoys from Lüneburg, so foraging for mealies and slaughtering the captured livestock became the principal occupation of the soldiers who were on half rations. Other casualties from both sides were the huge herds of springhok and blesbok which were still found in the area. On 28 February Lt-Col St G C Henry's mounted infantry was sent into Swaziland with a force of 200 men and a 'Pom-pom' some 20 km east of Ndhlozana where, in extremely rugged country, it met with stiff opposition. On the following day, Smith-Dorrien heard of a Boer convoy moving north from Mahamba along the Bremersdorp wagon road and sent reinforcements and food to Henry with an order to move south. It was the transport convoy of the Piet Retief Commando and Henry took 65 prisoners, including Asst Field-Cornet/Adjutant K P van Dyk, 27 wagons, 2 000 head of cattle and 2 000 sheep. One burgher was killed and two wounded as the rest of the commando under Cmdt C L Engelbrecht broke southwards only to be taken prisoner at Zandbank where Col W P Campbell's column had relieved that of Allenby's that day. By 2 March, Smith-Dorrien noted that the Swazi were looting Boer homes and driving the women away in terror to be brought in by the British troops.(56) Allenby moved further east and camped inside the Swaziland border at Mahamba. Henry continued to operate well inside Swaziland in the Mahlangatja Hills south-cast of Mankayane and on 4 March reported that the Swazi had located a Boer wagon convoy some 20 km to the east. On the following day, Smith-Dorrien noted that 'The Swazi Queen has called out her Impis to attack the Boers and clear them out of her country'.(57) Henry returned to Derby on 9 March with eighteen prisoners, nine wagons and two carts, 400 head of cattle and 500 sheep; British operational losses in this rugged country were thirty horses from exhaustion. Operating in wet and cold weather, the columns of Campbell and Allenby continued to press northwards into Swaziland from the southern border, watching the drifts on the Mkhondvo River and patrolling as far as C Warren's store in Mahlalini south of Hlatikulu, thus squeezing the burghers into the hills of south-western Swaziland.

Swazi attack

Whether or not Smith-Dorrien intended to bring the Swazi

into the conflict, at least one soldier, a private with the

Devonshire Regiment in Piet Retief was convinced that,

in addition to French's eight columns, there was 'a ninth

column, commanded by the Queen of the Swazis'.(58)

Responding to Smith-Dorrien's message, the queen-regent

sent out instructions to drive the burghers out of the

territory. To the south she sent Thinthita waMvikiviki

Dlamini, an experienced but headstrong indvuna from

the Ndhlavela regiment who had fought against the Pedi

in 1879. His orders were to instruct Chief Ntshingila

Simelano and Mnt Ndabazezwe waTsekwane Dlamini,

the two most powerful men in southern Swaziland, to

drive the Boers across the border. One group of men from

the Piet Retief Commando, with seven women and

twelve children, some cattle and five wagons were in

camp some eight kilometres north of Bouwer's Hoogte

near the present site of Hlatikulu. On Thursday, 7 March,

Ntshingila sent a message to the party that he wanted to

talk with them and demanded a grazing fee of two oxen.

One burgher, W Whitman, took two of his oxen and did

not return. On the following morning some forty Swazi,

two of whom had rifles and the rest assegais and kerries,

returned with one of the oxen. The burghers went out to

meet them, but at a pre-arranged signal from Thinthita

the Swazi surrounded and attacked the group. Some

burghers escaped on horseback whilst the women and

children fled. Thirteen burghers and one African with

them were killed, several wounded and all their cattle

taken.(59) The remainder of the party, ten burghers and

their families, together with a nearby laager, trekked

southwards to the border where they surrendered to the

18th Hussars on the farm Zandbank on 9 March.(60) From

8 to 11 March, Allenby's column was on patrol from

Mahamba and during this time 69 burghers with 20 wagons

and many women and children surrendered; the massacre

had caused a panic.(61) One party with three wagons was

held up by Mkhondva River swollen by incessant rains,

a burgher dying from assegai wounds in the stomach.

Both the queen-regent and Ntshingila denied involvement

in the incident. Ndabazezwe reported to B Colenbrander,

the resident magistrate at Ngwavuma, that both he and

Ntshingila had ignored Thinthita's demand and that it

was the indvuna who had collected a small imphi

and attacked the Boers. According to Ndabazezwe, the

imphi carried no shields to allay suspicion and attacked

with assegais only; Ntshingila sent Thinthita and all the

Boer cattle to the queen-regent.(62) Allenby immediately

sent a note remonstrating with the queen-regent for the

massacre and ordering local chiefs to surrender the cattle

they had taken contrary to his orders; within a few days,

some 100 head had been returned.(63) French recorded that

he too had sent a letter to the queen-regent 'warning

against practice of barbarities towards Boers and theft

from White residents.'(64)

Gravestones of burghers killed by a Swazi imphi

on 8 March 1901, Hlatikulu Kop

(Photo: H M Jones).

On 24 March Allenby's column moved eastwards from Mahamba further into Swaziland. During its first bivouac on H Muller's farm Plat Nek the indvuna of the royal homestead Zombodze emuva, Silele Ntsibandze, was very co-operative. As the column moved on, numbers of armed Swazi arrived to fight with the column but they were sent home with the exception of a few who were retained as guides. Allenby made his main bivouac at J C Henwood's store and soon met the missionary Malla Moe who had returned to the Bethel Mission. Allenby was unable to catch up with a Boer party that he had been following, but at Langdraai a drift across the Phongola River, Swazi guides found one 15-pounder gun (captured from the British at the battle of Colenso on 15 December 1899) and two Pom-poms which had been buried in the sand. They were rewarded with £25 for each gun. Moe entertained Allenby aud his officers from her meagre supplies and became almost infatuated with the future field-marshal. Just before the column started to retrace its steps westwards on 8 April, she presented Allenby with a Zulu grammar book inscribed 'Colonel Allenby with remmeberances [sic] Malla Moe'.(70) As the columns of Smith-Dorrien, Allenby and Campbell withdrew to Middelburg and Wonderfontein on the Delagoa Bay railway, pressure on the scattered commandos around the south-western borders of Swaziland eased.

Further north, Johannes Smuts tried to visit Swaziland to explain the situation Leaving Pretoria on 8 April 1901 with Miller, still acting as his secretary, and his former interpreter, D Macebo, he arrived five days later in Barberton where he reported to Stephenson. Probably to his intense chagrin, Smuts found that Bremersdorp was occupied by a detachment of some 100 men from Steinaeker's Horse and that Von Steinaecker himself was there. The latter had been instructeo to send an escort to Nomahasha to meet Smuts, but replied on 23 April that Smuts should postpone his visit as he was short of horses. Smuts's report compiled two days later was vitriolic in its treatment of Von Steinaecker. He reports that the queen regent, through Mhlaba, a Shangane indvuna at Forbes' Reef, had said that the soldiers in Bremersdorp were not English, but only men who used to work in Swaziland. Stephenson was advised by Smuts that Von Steinaecker's request for Mbridula Maziya to be rewarded for his services with 250-300 head of cattle should be turned down.(71) Smuts eventually reached Bremersdorp in early May where he told Brother I F Swinhoe, who had returned to Usutu Mission Station with Brother S F Harp in September 1900, that he was enquiring into the damaging of houses in the town. Swinhoe reported that the rains had been late and that there was a lot of fever. Of the 80 or so men in Steinaecker's Horse in Bremersdorp, at least 30 were down with fever and they had no medicines. At the mission, work was going well with a full church each Sunday, but in spite of considerable help from the troops who were most kind and considerate, provisions were low and Frank Dlamini with six other Swazi had to go to Nongoma for sugar, salt, soap and candles.(72) At Ndhlozana, the Mercers, having been evacuated, headed for Britain and shortly after their departure the mission was looted, first by Swazi and then by Boers.

Whilst Smuts was away from Pretoria, Milner had come to the conclusion that Swaziland would best be administered as a department of the Transvaal. With I Chamberlain's concurrence, Milner telegraphed Smuts that it had 'been decided that Swaziland shall be treated for the present as a dependency of the Transvaal. You should therefore address any reports or telegrams to Secretary to Administrator, Pretoria, not to me'. Smuts's hopes to become the first British administrator in Swaziland received a severe setback.(73)

Boer incursion: Bremersdorp razed

Swaziland remained an important communications route

for the commandos and on 4 July 1901 two men carrying

despatches for the Boer command were killed in hand-to-hand

combat by Lt J A Baillie and L/Cpl W S Harris of

Steinaecker's Horse; both mentioned in despatches. Baillie

was later awarded the DSO and Harris the DCM. The

men were shot on the Lubomb and were apparently

dressed in Portuguese uniforms. Some reports said that

they carried only newspaper cuttings while others stated

that despatches from Europe had been sent to Kitchener. (74)

The queen-regent, playing both sides in the conflict, became uneasy with the detachment of Steinaecker's Horse in Bremersdorp which by July numbered some 110 men of whom twelve were on the sick list.(75) Capt I B Holgate had ordered the execution of a Swazi as a spy and arrested Mancibane waNdlaphu Dlamini for supporting the Boer cause: Mancibane had been well-known to Cmdt-Gen Joubert and was also a friend of M J J Grobelaar. Steinaecker's Horse was also accused of looting cattle which were allegedly sent to St Lucia Bay for safekeeping. Accordingly, the queen-regent advised Cmdt-Gen Botha that Bremersdorp was occupied by robbers who should be removed. From Ermelo on 16 July 1901, Botha sent orders to Asst Cmdt-Gen F Smuts to take his commando into Swaiziland and, without molesting the Swazi nation in any way to destroy the robbers and shoot on sight any armed Africans operating with them. The Swazi National Council had given permission for this to be done and Smuts was asked to arrange a meeting in conjunction with Grobelaar to tell the council not to allow the country to be used as a hiding place for murderers and robbers. In this, as in other cases, the British military had failed to act in concert with the civil authorities and there seems to have been genuine doubt on the part of both Swazi and Boers that Steinaecker's Horse was a legitimate British unit.

The Ermelo Commando with a few burghers from Carolina left Spitzkop for the border on 21 July under the leadership of T Smuts and Cmdt J L Grobler. A patrol to the western border, which returned to Bremersdorp at midday on 21 July, reported the approach of the commando. At l4.00, Von Steinaecker left for Barberton, having conveniently been summoned there. On the afternoon of the followiug day, Swazi messengers from the queen-regent arrived with the news that the commando was at the Hlambanyati. In command of the detachment was Capt A D Greenhill-Gardyne with Capt H O Webb-Stock as town commandant. As Von Steinaecker had left without nominating an officer in overall command the news prompted a dispute botween Gardyne, claiming seniority as a regular officer, and Webb-Stock, a colonial volunteer who had served with Bethune's Mounted Infantry. It was Webb-Stock, however, who that evening sent out a patrol of 25 men under Lt C P Major with orders to patrol as far as the Lusutfu River or until it located the commando. Should Major come into contact with the Boers, he was to send a message back and take up a position to block its advance. The rest of the detachment would then take up a position on Black Hill (Mnyameni or Lugoba Hill) to the west of the town. Major reached the Mhlahlane Spruit when another messenger from Zombodze reported that the commando was now coming down the Buffelshoogte. A message to this effect was sent to Webb-Stock, Major adding that he was falling back to the Black Hill with his patrol.

That evening the detachment's wagons were loaded and Webb-Stock announced that he was going with them to the Black Hill to laager at Bester's before joining Major. At this moment, Gardyne insisted that he was in charge and the detachment would take up a position at Loch Moy on the ridge east of the town with pickets on the hill above the Transvaal residency and gave orders accordingly. Lt E Holgate remonstrated that his brother Capt J B Holgate and Webb-Stock were taking their position on the Black Hill, but Gardyne replied that he was not having his line of retreat cut and at 21.00 he trekked eastwards. The wagons were taken beyond Makahlaleka's Spruit and outspanned whilst Gardyne took up a defensive position around Loch Moy with Holgate and 25 men in a forward position above the Transvaal residency. No-one had told Major of this move and, as the sun rose on 23 July, he thought he saw men of the detachment in the town and sent Tpr T G Butler to ascertain the situation. On reaching the Mzimnene River, Butler was taken prisoner. At daylight, Major with Sgt Smethwick and four men rode down to the Mzimnene. Smethwick sensed that there were Boers in town and hung back, but Major and the others had crossed the river when they were fired upon. Turning around and galloping back, the group was intercepted where the Raleigh Fitkin Hospital is situated today by a burgher called De Wienaar. At Bester's trees, Major halted and told his men to surrender, albeit De Wienaar was alone. The burgher rushed at Major and tore off his stars of rank and bandolier, saying 'You call yourself an officer - you are a cur'. In the meantime, Smethwick and the rest of the patrol rode off past Zombodze and eventually reached Komatipoort.

The commando had surrounded the town during the night, only to find that the bulk of the detachment had moved eastwards. Scouting at daylight near the Transvaal residency on the eastern side of the town, M S Thring was the first to notice burghers riding up from the river. He was fired at, but returned to Holgate's position. Half-an-hour later some 50 to 60 burghers came riding eastward and, contrary to instructions, one nervous trooper fired when they were still 400 yards (366 metres) away. Even so, they scattered back to town only to return with twice the number and Holgate retired to Gardyne's main position. As he rode up, pursued by the burghers, however, panic ensued and the cry 'Every man for himself' saw officers and men upsaddle and ride eastwards. Sgt K B Wilcoxon, who was technically under arrest for drunkenness, fired on the burghers and tried in vain to rally the men. At Helehele Nek ('The King's Offsaddling Nek') which was then wide enough only to take the wagon road Gardyne tried to rally the men, but Baillie thought that the 60 to 70 burghers who followed were too many so he upsaddled and left. Gardyne was left with no alternative but to give the order to mount. As the men reached Makahlaleka's Drift, they were fired upon by a Boer Maxim from the ridge above. Towards the end of the fight, the detachment's Maxim jammed and Sgt A J Miller, who was in charge of it, was killed along with an African called Scotchman. Above the spruit, at the current site of St Joseph's Mission, the Boers captured the wagons which were loaded with 30 000 to 40 000 Lee Metford cartridges, one Maxim gun and some £900 in cash. The commando took 33 prisoners and returned to Bremersdorp where, at about 11.00, the burghers started to burn the town. Everything was destroyed, including the plant on which The Times of Swazieland had been printed. On its return, the commando laagered at Lanqabane near Lozitehlezi and the queen-regent was presented with some of the 500-600 head of cattle which had been taken by the burghers. Mnt Mancibane was released and given one of Von Steinaecker's wagons, the commando taking a further eleven with them. T Smuts and Grobelaar met the queen-regent and council and passed on Botha's message and the queen-regent thanked the commando for its actions.

It is difficult to assess the casualties from this action. Officially, four men of Steinaecker's Horse wore killed (76) and four others seriously wounded and subsequently discharged as medically unfit. T Smuts, however, reported that eighteen to twenty of Steinaeckor's Horse had been killed, eight wounded and 41 taken prisoner. The British lists report no prisoners, but undoubtedly there were.(77) Among them were four surrendered burghers (Hensoppers) from Ward II of the Ermelo district. Returning to Amsterdam, they were court-martialled: M G Joubert was sentenced to death on 27 July and shot the same day in front of the commando 'according to military fashion'; J Tosen was given ten lashes and fined £25; William Tosen was given 25 lashes; and C Viljoen was given fifteen lashes and fined £15. T Smuts believed that a further sixteen burghers with the detachment escaped. There is no evidence of these surrendered burghers in the various muster rolls or among the attestation papers, but they were definitely with Steinaecker's Horse with Families, their wagons and cattle being among those taken by the Boer commando.(78) The commando's only reported casualties were two wounded burghers, but there were probably more.(79) After the detachment of Steinaecker's Horse was driven from Bremersdorp, the 1st Alexandra Princess of Wales's Own (Yorkshire) Regiment, occupying blockhouses along the railway line from Kaapmuiden to the border, was alerted that the commando was heading north-eastwards towards Komatipoort. This post was then reinforced by 50 men from Barberton and 50 from Kaapmuiden whilst patrols under Capt H R S Maitland, 2/Lt C H Marsden and 2/Lt B C D Nash-Wortham were immediately sent into Swaziland. When it became obvious that the commando had retired to the Republic, the patrols were withdrawn.(80) Returning to the Republic, T Smuts reported to Cmdt-Gen Botha on 29 July. As an afterthought, he added a postscript: 'NB. As Bremersdorp was used as a refuge for robbers and handsuppers [sic], I have burned the town to ashes'. Commenting that Smuts had 'acted absolutely contrary to our principles in burning to ashes the town of Bromersdorp', Botha suspended him from duty as of 18 August and, on 31 August, his suspension was confirmed and he was discharged as an assistant commandant-general. Smuts complied, but pointed out in a letter dated 2 September 1901 that where the British were using houses outside the Republic's borders to promote their operation his actions were valid. He also stated that most of the burghers on commando had urged him to burn the town, a course probably suggested by the fact that by this time, the eastern Transvaal had been devastated by British troops.(81) In response, Botha noted that Smuts had refused to give the explanation requested and to meet personally with him at Bankkop to discuss the matter.(82)

In his vitriolic remarks about Steinaecker's Horse, Johannes Smuts had been particularly disparaging about the Scot, Alexander McCorkindale, who lived at Ndsingoni east of Pigg's Peak 'a burgher, and a notorious drunkard and bad character [who] seems to have charge of the Pigg's Peak district and if reports are true has been indulging in looting and gun selling'. As we have seen, McCorkindale had certainly been active. Born in Scotland, he may have been registered as a burgher, but had attested as No 1105 Trooper Alexander McCorkindale at Komatipoort on 6 July l900.(83) On 30 May 1901, the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons picked up two burghers at the Sheba Queen Mine in the upper Nkhomati valley who had been shot and seriously wounded by McCorkindale.(84) The gold mine had managed to maintain sporadic production throughout the war, but in the spring of 1901 came news that a commando was coming north through Swaziland. Steinaecker's Horse moved from Pigg's Peak and met the commando, which seems to have been a remnant of the Ermelo Commando, in the Nkhomati valley. Prisoners were sent to Barberton and the old men, women and children were put onto their wagons and left to find their way back across the border.(85)

Further incursions

Later in the year, as the blockhouse line was extended

from Wakkerstroom to the Swaziland border, Lt-Col A E

W Colville's column swept repeatedly through the area,

forcing small parties of burghers into Swaziland. Some

of these, under the command of Asst Cmdt-Gen C Botha,

were returning from Cmdt-Gen L Botha's unsuccessful

second invasion of Zululand and Natal, crossing into

Swazi territory to evade the blockhouse line.(86) On 8

November, Maj B A Wiggin, 13th Hussars, with a detached

force of the 26th Battalion Mounted infantry from

Colville's column, captured a laager near Mahamba and

took fourteen burghers prisoner; among them the landdrost

of Piet Retief, T A Kelly, who had served with the

Swaziland Commando, and C J van Rooyen, field cornet

for Ward I (Assegai) of the Piet Retief district adjoining

the Swaziland border.(87) Another laager was attacked a

week later when twelve burghers and nineteen wagons,

with their teams, were taken by Wiggin's force at Plat

Nek, well inside the border.(88) Colville pushed eastwards

as far as Bethel, where Malla Moe was accused by local

burghers of sending for British troops. He left the

missionary to look after the families of the captured

burghers.(89)

In the meantime, Forbes had been acting as guide for Brig-Gen J C Dartnell's column in the eastern Transvaal from late January, along the Zululand border in March and then in the Free State. In September he was sent to join Brig-Gen J Spens's column in a similar capacity in Natal. Recalled to Pretoria, Forbes was appointed captain in the Field Intelligence Department on 7 December 1901 and was instructed to raise a unit known as the Lebombo Intelligence Scouts. By this time, the activities of Steinaecker's Horse were essentially limited to garrison duty at Pigg's Peak, Komatipoort and the Sabi River, and the Lebombo Scouts were raised to intercept messengers moving between the commandos and Lourenço Marques. It has been stated that this was one of the burghers' corps established in 1901, but the available evidence suggests that this is too simple a classification.(90) The unit certainly included men who had served with the Swaziland Commando and who risked their lives if captured by the Boer commandos; it also included men who were definitely not burghers, as well as several who had served with Steinaeckor's Horse. What they seem to have had in common was a knowledge of the country in which they were expected to operate, but the war had created divided loyalties and severe tensions within families and communities. Two of Forbes's sergeants, Willem A and Cornelius R McSeveney, were from Ferreira's Station and Mantambi respectively; their father was a Scottish immigrant who had married an Afrikaner wife in Potchefstroom and the sons, like Forbes, were burghers. Unlike Forbes, however, they were brought up as Afrikaners and not as British. Forbes, with Lt A M Miller as his second-in-command, came to Komatipoort from Barberton, where most of their recruiting had been done, and then moved southwards through the Swaziland highveld to Ngwavuma Poort. Their camp was established on the Lubombo range above the poort. Near Sihlutse, Cmdt N J M Vermaak had established a laager which was attacked by Forbes and some twenty scouts in early February 1902. During the brief fight, Vermaak was fatally wounded and taken by Forbes to Malla Moe's mission where he died and was buried. According to the missionary, Forbes was most kind to her and evacuated all the Boer families from the mission. Forbes had been helped by Swazi guides, the most prominent of whom was Tshingana kaTole who was given the task of taking a message into Vermaak's laager, for which he was rewarded with four head of cattle. This was the last action of the war in Swaziland and, for a few months only, the country resumed its independent status.

Post-war Swaziland

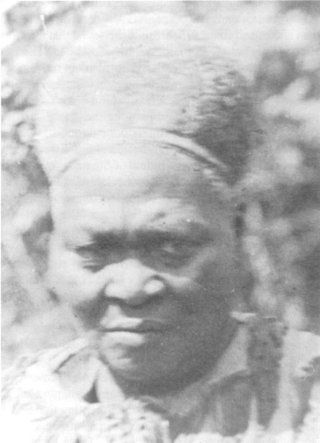

The Queen-Regent, Gwamile Mdluli (Labo Tsibeni),

13 April 1917

References

6. Details of the 'Swaziland Expedition' are from The Times of Swaziland and South Africa, supplemented

with information from Major G Tylden, The armed forces of South Africa, (Johannesburg, 1954).

7. PRO DO 119/572, affidavit by J J Bennett, Cape Town, 5 July 1900.