The South African

The South African

D W Aitken

Dudley Aitken is the curator of the Edged Weapons and Flag collections at the South African National Museum of Military HistoryIntroduction

Important railway junctions and stations in the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (the Transvaal) fell to the British in rapid succession after the main British Army under Field Marshal Lord Roberts crossed into the Transvaal from the Orange Free State in late May 1900. On 27 May 1900, the British Army headquarters occupied the railway station at Vereeniging, the southern terminus of the NZASM. Elandsfontein, the key to the Transvaal railway system, was occupied on 29 May in full working order and, on 1 June, Colonel Girouard DSO, Royal Engineers, took charge of the railways in Johannesburg. On 6 June 1900, the British occupied Pretoria Station and on 8 June locomotive and traffic officers of Colonel Girouard's staff arrived in Pretoria. British military rail traffic was started to the south of Pretoria, to Waterval on the Northern Line from Pretoria, and to the British army outposts near Eerste Fabrieken, sixteen kilometres from Pretoria on the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway Line. In June 1900, NZASM officials were deported and the Transvaal railway network was incorporated into the Imperial Military Railways system. Soldiers with railway experience were called upon to volunteer for work on the Imperial Military Railways. Those selected received, in addition to their regimental pay, engineer remuneration at rates which varied according to their qualifications.(1)

On 23 July 1900, the British Army began their advance eastwards along the Delagoa Bay Railway Line. For some weeks the 11th Division and mounted troops had been encamped near Lerste Fabrieken, the eastern railhead for the British. A supply depot had been formed at this point.(2) A construction train, fully equipped to cope with anticipated damage, left Pretoria and on 24 July began work on a small bridge near Van der Merwe Station. The British Army made rapid progress along the railway while the railway construction engineers followed closely on their heels carrying out the necessary repairs along the line. This included deviation works at two large bridges over the Bronkhorstspruit and Wilge rivers, which were completed by 6 August l900.(3)

Besides attending to the necessary defence of that portion of the line already under their control, the Royal Engineers also constructed auxiliary platforms and installed portable electric lights and supplementary water supplies at some stations to cope with the military traffic using the line.(4)

On 13 September 1900, the construction train commenced work on a large bridge that had been destroyed near Godwan Station in the Elands Valley. Troops of the 11th Division kept guard. By 25 September 1900, when Komatipoort Station had been occupied by the British Army, the entire Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway was ready for use by the British.(5)

The British defence of the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway

The first major task undertaken by the British authorities controlling the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway after the capture of Komatipoort Station was the transportation back to Pretoria of most of the British force which had been used during the advance drive into the east. Between 26 September and 10 October 1900, a total of 102 trains were used to transport these troops back to Pretoria. From the beginning of October 1900, owing to the presence of ZAR forces near the line who used every opportunity to attack and damage the railway, the running of trains at night on the line between Pretoria and Waterval was suspended. Some of the troop trains returning to Pretoria came under fire along certain sections of the line and it became clear that suitable defence was essential if the British were going to be able to continue to make use of the railway(6)

One of the first reforms introduced by Lord Kitchener when he assumed command was the strengthening of the railways. In October 1900, the railway defences were rudimentary, consisting of open trenches at stations, bridges and culverts, while the line itself was patrolled by small parties of mounted men. In laying out the trench defences, the principal object was to render them inconspicuous and thus immune from artillery fire. The system required enormous numbers of troops, both for patrol work and for manning the long lines of trenches. Thus, it was not long before it proved to he both inefficient and wasteful.(7)

The number of successful attacks carried out on the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay line by ZAR forces in October 1900 soon illustrated the inadequacy of the railway defence system. On 1 October, for example, the ZAR forces derailed a train at Pan Station. There were 300 British troops on board. Twenty-three were killed by the terrific fire which was directed at the wreckage of the train during the attack. On 6 October, an engine was blown up and five trucks derailed at Balmoral Station; the next day a culvert was destroyed at Brugspruit, east of Balmoral; and two days later a train was derailed at Kaapmuiden.(8) It was only too obvious that the defence of the line was far from satisfactory.

Lord Kitchener was determined to stamp out attacks on the railway. On 26 October 1900, he ordered the troops under Smith-Dorrien to undertake active offensive operations against the burghers who were interfering with the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway. The headquarters of the railway attackers was traced to a laager at Witkloof, located thirty kilometres south of Belfast, and British troops raided this area on 2 November and again on 6 November. Fierce fighting took place along the Komati River. Attacks on the railway line did not cease after the raid and the British forces continued their policy of raiding and burning farms which were being used by the burgher forces as launching sites for attacks on the railway. The climax to the British raids took place on 13 and 16 November 1900, when the flour mills and a number of houses were destroyed at Witpoort and Dullstroom.(9)

The British policy of burning and raiding farms in the vicinity ofthe railway in an attempt to stop attacks on the line did not have the desired effect and attacks by the ZAR forces not only became more frequent but also more destructive. In December 1900, Helvetia was attacked and 250 British troops, mainly prisoners, and a 4,7-inch gun were captured while the Republican forces were planning a large-scale attack on five big railway stations on the railway, namely Machadodorp, Dalmanutha, Belfast, Wonderfontein and Pan, in early January. Other methods of defending the railway would have to be used if the line was to be successfully defended.(10)

The large-scale attack by the Republican forces on the stations mentioned above took place on 7 January 1901. The biggest attack took place at Belfast, during which the British lost 71 men and fought desperately to prevent the entire town from falling to the Boers.(11)

The British Army had made a close study of the use of railways in times of war and of the various methods of defending a railway from enemy attack. Railways had played an important part in the American Civil War (1861-65) and contributed greatly to the success of General Sherman's campaign. Railways had also played a major role in the Italian Campaign of 1859 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the British Army experts could use the knowledge gained in these previous wars.(12)

The 8th (Railway) Company, Royal Engineers, was sent to the Cape in July 1899 and a Department of Military Railways was created with Major Girouard, RE, in charge as 'Director of Railways for the South African Field Force'. A number of other Royal Engineer officers who had experience of railway work in India served as assistant directors or staff officers in various capacities. These men and their staffs now built up a railway system in South Africa that would be run on strictly military lines with military efficiency.(13)

To improve the defence of the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway, the British Army began to make increasing use of two particular inventions from January 1901. These were the armoured train and the blockhouse system with its wire entanglements and other obstacles, including deep trenches and alarm systems such as spring guns, flares and tin cans tied to wire fences. What follows is a discussion of the use of these inventions in defending the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay line.

During the Anglo-Boer War, the armoured train was developed possibly to its climax, both in manner of employment and in organization. In the first year of the war, the use of armoured trains had proved disastrous but slowly a sensible control system was established. Captain H C Nanton, RE, was appointed Assistant-Director of Armoured Trains and he was responsible for controlling all of the armoured trains in South Africa. Nanton saw to it that all armoured trains were used in the best manner possible and carefully defined the purpose and duties of these trains.(14)

The armoured train was virtually a fortress on wheels

and a typical one used to defend the Delagoa Bay line

from January 1901 would have comprised the following,

as seen from front to rear: (15)

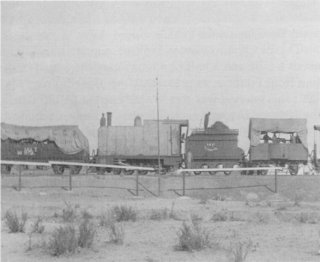

A British armoured train, manned by soldiers and armed

with a Maxim machine gun, during the Anglo-Boer War

(Photo: SANMMH)

Towards the end of 1901, there were more than twenty armoured trains in service in South Africa, but even this number was insufficient to protect all the ordinary trains. An armoured wagon, a standard bogie wagon protected by lengths of rail in clips to a height of five feet with sleeper-mountings at each end for Maxims and a canvas awning cover, was therefore coupled to an ordinary train to defend it in case of attack.(19)

A typical British armoured train during the Anglo-Boer War

(Photo: SANMMH)

Nevertheless, the so-called 'Blockhouse System' introduced by Lord Kitchener in January 1901 to fence off the country, was also a vital element in the successful defence of the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway during the last fifteen months of the war. The first blockhouses were built along the railways as a means of protecting the lines from attack by raiding parties. Later, the system of blockhouses was extended across the open veld in some parts until eventually there were some 8 000 of these structures in South Aflica, usually spaced between half a mile and a mile (0,8 to 1,6 km) apart.(21)

The number and intensity of the Boer attacks on the Pretoria-Delagna Bay Railway continued to grow steadily during the last two months of 1900. Thus it became increasingly clear that some form of permanent or semi-permanent defence was urgently required if some level of security was to be achieved and the number of railway guards reduced. Early in January 1901, therefore, the first blockhouses were constructed and by March 1901 blockhouses were being built along the Delagoa Bay Railway. As the ZAR forces had lost most of their artillery by January 1901, shell-fire no longer presented a great threat to the blockhouse. The open trenches alone the railway were replaced by closed works, allowing for a wide field of fire, and they were also protected from assault by barbed wire entanglements and other obstacles.(22)

At important bridges along the line, the blockhouses were built in the form of substantial stone forts, the construction of which required much labour and time. The majority of blockhouses consisted of small, octagonal structures made of two skins of corrugated iron nailed onto wooden frames, the space between being filled up with gravel and earth. To enable the defenders to fire at anyone attacking the blockhouse, loopholes were formed by drilling through the centre of steel plates and these were placed either on wooden cases which rested on the gravel or on wooden cross-pieces. This early type of blockhouse had many disadvantages - it required a regular foundation, the loopholes were complicated and inefficient, construction was slow (involving the transportation of much of the material and the necessity of having experts on site) and it soon proved to be too expensive and too elaborate.(23)

In February 1901, Major Rice RE devised a new pattern for the building of blockhouses. While the octagonal shape was retained, the two skins of corrugated iron were placed only 11 cm apart. Both skins were nailed to a single wooden frame and the space between the skins was filled with hard shingle to prevent penetration by bullets. The blockhouse stood on a platform of stone and/or earth, which was about four meters in diameter and 30 cm high. Around this platform was raised a bank of unrammed earth which reached a height of some twelve metres and was a metre thick at the top. Through the corrugated iron sheets, twelve loopholes were cut at a height of 120 cm from the ground inside the blockhouse. The loophole was formed of sheet iron in the shape of a double funnel with the neck in the middle of the wall. A roof of corrugated iron was placed on top of the blockhouse to give protection from the sun and rain.(24) Outside the low earthwork which formed the lower part of the blockhouse ran a trench and beyond that, though not in every case, was a complicated entanglement of barbed wire. Tins suspended on sticks on the wire gave audible warning by tinkling whenever anyone approached and attempted to pass through the entanglement. These measures were introduced to prevent the enemy from stealing up at night and firing through the loopholes.(25)

Although blockhouses were being built along the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway as early as January 1901, progress in attempts to improve the defence of the line in the face of frequent attacks by train wreckers such as Captain Hindon and his men, proved to be slow and unmethodical. This continued to be the case until March 1901, when Major Rice again introduced a new type of blockhouse.

Each blockhouse was furnished with a small, cylindrical water-tank of corrugated iron. To produce these, iron sheeting had to be rolled in a machine to give it the proper curve and, in observing this process, the idea of the circular blockhouse occurred to Major Rice. The new pattern proved to be an immediate success and became the standard pattern used on the Delagoa Bay Railway and elsewhere in South Africa from March 1901.(26)

This new blockhouse consisted of two corrugated iron cylinders without any woodwork, the space between the cylinders being packed with shingle, and the whole structure roofed and loopholed as before. These blockhouses were more durable than the octagonal form which tended to bulge, and they were also much cheaper to build, requiring little material or transport or skilled labour, and proved very successful in defending the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway.(27)

Such was the progress made with the construction of the new circular form of blockhouse during March and April 1901 along the Delagoa Bay line that by May most of the line between Pretoria and Komatipoort was well-protected. The blockhouse garrisons, working in conjunction with the crews of the armoured trains that were also steadily increasing in number and improving in efficiency, took over the work of patrolling and defending the railway from the mounted patrols and an immediate improvement in the defence of the line was noticed.(28)

The blockhouses were initially constructed only at stations, bridges, culverts, important cuttings and curves along the railway as these proved to be most vulnerable to attack by enemy raiding parties. With the introduction of the new circular blockhouse which could be manufactured and erected cheaply and rapidly, however, the function of the blockhouse was extended to serve the additional purpose of converting the railway into a barrier against the free passage of the enemy.(29)

This new function of the blockhouse was put to the test on 27 June 1901 when General Ben Viljoen and about 600 men attempted to cross the railway between Balmoral and Brugspruit. In describing the events which followed, General Viljoen wrote:(30)

'The blockhouses were only 1 000 yards (914 metres) distant from each other, and in order to take our wagons across, there was but one thing to be done, namely, to storm the two blockhouses, overpower their garrisons, and take our convoy across between these two ... When 150 yards (137 metres) from the blockhouses the garrison opened fire on our men and a hail of Lee-Metford bullets spread over a distance of about four miles (6,4 km) the British soldiers firing from within the blockhouses and from behind mounds of earth. Our men thrust their rifles through the loopholes of the blockhouses and fired within. Meanwhile the fight at the other blockhouse continued. Commandant Groenwal afterwards informed me that he had approached the blockhouse and found it built of rock; it was in fact, a fortified ganger's house built by the NZASM. He did not see any way of taking the place - many of his men had fallen and an armoured train with a searchlight was approaching from Brugspruit. On the other side ofthe blockhouse we found a ditch about 3 feet deep and 2 feet wide. Turning the searchlight on us, the enemy opened fire on us with rifles, maxims and guns, firing grape-shot. The searchlight made the surroundings as light as day, and revealed the strange spectacle of the burghers, on foot and on horseback, fleeing in all directions and accompanied by cattle and wagons, whilst many dead lay on the veld.'

The blockhouses were built at regular intervals of about a mile and a half (2,4 km) along the extent of the line from Pretoria, as previously mentioned. From May 1901 this interval was steadily lessened until, ultimately, the distance between each blockhouse was reduced to as little as 400 yards (366 metres). The barbed wire entanglements and the till cans which served as a warning device to the garrison, as well as barbed wire on either side of the shoe of the railway track and the additional trenches made it very difficult, if not impossible, for the ZAR forces to drive wagons or carts onto the line to block the path of oncoming trains.

The garrisons of the blockhouses along the Delagoa Bay Railway were instructed to fire upon anything seen moving after dusk and wild animals, stray horses, oxen and even ostriches paid the penalty for venturing near the line.(31) Flares, ignited by a string, which led up to one of the nearest blockhouses, lit up the veld whenever the enemy was thought to he attempting a crossing. Rockets were always at hand to call in the help of the nearest armoured train.(32)

As increasing numbers of blockhouses were erected along the Delagoa Bay line, attacks on the line became increasingly more difficult to carry out. Even Captain Hindon and his determined hand of train wreckers decided the Delagoa Bay line was too well defended and left for the northern Transvaal towards the end of July 1901.(33)

The growth in the number of blockhouses throughout 1901 also created problems for the British Army, as a large and ever-expanding number of men was required to man them. At first, there had been ten to fifteen men to a blockhouse, but with the construction of more of these structures, the number of available men per blockhouse decreased. (Reinforcements from Britain did not substantially increase the total strength of the army.) From the initial ten men, the blockhouse garrison was reduced fewer men could be spared for this work, although the effect of the fire of so few rifles, especially in the dark, hardly presented a formidable deterrent to a determined attack on the railway or an attempted crossing of the line by a cunning enemy.(34)

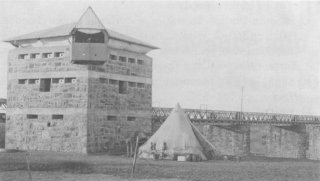

A blockhouse, made of two skins of corrugated iron nailed

onto a wooden frame, situated two miles east of Pretoria, June l902

(Photo: SANMMH)

A stone blockhouse, used for guarding the railway bridge

(Photo: SANMMH)

From August 1901 , the British columns began to use the Delagoa Bay Railway as a barrier against which to drive and trap the scattered Republican forces. The main purpose of the blockhouse system by then was to prevent the ZAR forces from crossing the railway line and thus escaping the net that the British columns were continually trying to cast around the Boer forces.

Just before the conclusion of the Peace at Vereeniging in May 1902, Captain Hindon, the famous train wrecker who had caused so much damage and destruction along the Pretoria-Delagoa Bay Railway, especially in the period October 1900 to June 1901, surrendered with several of his men.(36) In August 1901, after Hindon and his men had destroyed a train at Waterval about 30 km from Pretoria, Lord Kitchener had stated:(37) 'Although it may be admitted that the mining of railways and the derailment of trains is in no way opposed to the custom of war wherever any definite object is in view, it is impossible to regard senseless and meaningless acts of this nature, which have no effect whatever on the general course of operations, as anything better than wanton murder.'

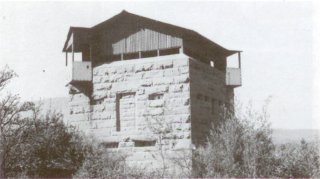

Octagonol blockhouse, Orange Grove, Johannesburg

(Photo: SANMMH)

A blockhouse of cut stone silhouetted in the botanic gardens

near Harrismith (Photo: SANMMH)

After the surrender of Captain Hindon and his men in May 1902, they were cleared of all infractions of the laws of war.

References

1. E P C Girouard, History of the Railways during the War in

South Africa (London, 1903), pp 39-40, 52.

2. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 43.

3. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 43.

4. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 43.

5. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 45.

6. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 46.

7. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 46.

8 Girouard, History of the Railways, p 46. See also H W Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War. Volume I (London.

1902). Note that these two sources give different dates for the derailment of the train near Balmoral Station:

6 October 1900 (Girouard) and 5 October 1900 (Wilson). These sources agree on the other dates.

9. H Smith-Dorrien. Memories of 48 years service (London, 1902), pp 260-2: Wilson. After Pretoria: The Guerilla War

(London 1902), pp 204 and 206. See also Gustav S Preller, Kaptein Hindon (Cape Town, 1916). pp 161-3.

10. Smith-Dorrien, Memories, p265. See also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 164-5.

11. Smith-Dorrien, Memories, p269. See also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 172-4: also Wilson, After Pretoria, pp 362-3.

12. E A Pratt, The Rise of Rail-Power in War and Conquest, 1833-1914 (London, 1915), pp 7-29. See also Royal

Engineers Institute, Detailed History of the Railways in the SA War (Chatham, 1904). p7.

13. Pratt, The Rise of Rail-Power, Chapter XVI. See also Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History, pp 7-9.

14. Pratt, The Rise of Rail-Power, p251. See also Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History, p 246.

15. Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History, pp 241-5.

16. Keith Davies, 'Armoured Trains' in War Monthly, No 18. September 1975, pp 43-6.

17. Davies, 'Armoured Trains'. pp 43-6. See also Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History, pp 248-50.

18. Wilson, After Pretoria. See also Ben Viljoen, My reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War (London, 1902). pp 382-6;

also Preller, Kaptein Hindon. pp 207-10: also Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History, p 240. Note that

Preller gives the number of Boers killed and wounded as 26, while Ben Viljoen gives the total number as 31.

19. Davies, 'Armoured Trains', p 46. See also Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History, p25.

20. Davies, 'Armoured Trains', p 46.

21. L S Amery (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902, Volume V, (London, 1907), pp 396-7.

22. Amery (ed), The Times History, p257. See also Wilson, After Pretoria, Volume I, p 379;

also Girouard, History of the Railways, p 67.

23. Amery (ed), The Times History, p 258.

24. Amery (ed), The Times History, p 258.

25. H W Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume 11 (London, 1902), p 69.

See also Viljoen, My reminiscences, pp 382-6 and Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 189-92.

26. Amery (ed), The Times History, p 258.

27. Amery (ed), The Times History, p 259. See also Girouard,

History of the Railways and Viljoen, My reminiscences, pp 44-5.

28. Amery (ed), The Times History, p 259.

29. Amery (ed), The Times History, p 259. See also Viljoen, My reminiscences, pp 357-8.

30. Viljoen, My reminiscences, pp 382-6.

31. Amery (ed), The Times History p 259. See also Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 848.

32. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 848. See also Royal Engineers Institute, Detailed History,

pp 249-50.

33. Preller, Kaptein Hindon, p 212.

34. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 848.

35. Girouard, History of the Railways, p 67.

36. Ben Viljoen, My reminiscences, p 990. See also Preller, Kaptein Hindon, pp 261 and 262.

37. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 692.

38. Viljoen, My reminisceaces, pp 485-6.

39. Wilson, After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Volume II, p 990.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org