The South African

The South African

Introduction

Buried in the footnotes of military history one often finds interesting stories of technology and technological innovations, the implications of which are only understood years later in retrospect. Unfortunately this material is not always well documented. While the history of the development of wireless telegraphy more than 100 years ago has received considerable attention over the last few years it is not generally known that as far as can be established, the first operational use of this new technology was in fact in South Africa during the Anglo Boer War of 1899-1902. The story of how this invention found its way to South Africa so soon after it was first demonstrated makes fascinating reading. (1)

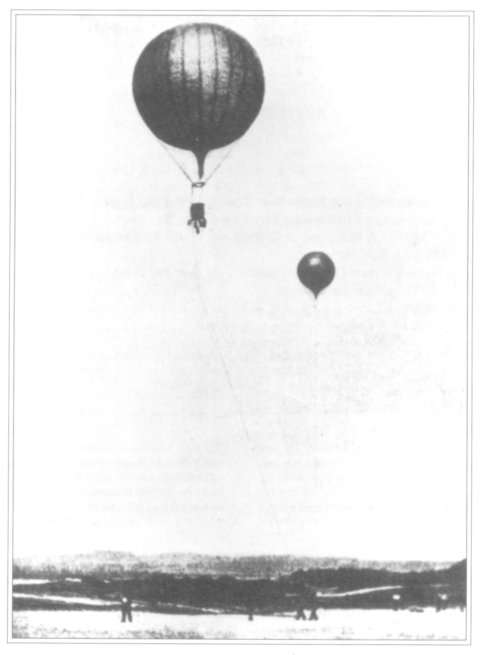

During the Anglo-Boer War, The Royal Engineers operated radio transmitters

which were served by aerials suspended from balloons.

(Photo: by courtesy of the Rosenthal Estate. Taken from Eric Rosenthal,

You have been listening ... A history of the early days of radio transmission in SA,

published by Purnell & Sons, Cape Town, 1974, opposite p9)

The title of this section inadequately describes the birth pains of a technology which continues to amaze us with its new developments - from untuned spark generator/transmitters to personal cellular radio and communication with spacecraft in the deep reaches of our solar system in less than a hundred years. Who could have foreseen that billions of people around the globe would view spectacles such as the Olympics and World Cup Football, taking place in countries and cities many of the viewers had not even heard of as these events were unfolding?

No single person can lay claim to the invention of radio. Many scientists and engineers contributed to the body of knowledge which made wireless telegraphy possible. These early pioneers included Faraday, Maxwell, Poynting, Heaviside, Crookes, Fitzgerald, Lodge, Jackson, Marconi and Fleming in the UK; Henry, Edison, Thompson, Tesla, Dolbear, Stone, Fessenden, Alexanderson, de Forest and Armstrong in the United States; Hertz, Braun and Slahy in Germany; Popov in Russia; Branly in France; Lorenz and Poulsen in Denmark; and Righi in Italy.(2) Despite the US Supreme Court's ruling in Tesla's favour in his longstanding patent dispute with Marconi, it is Marconi who is generally credited as being the inventor of wireless telegraphy as a means of conveying messages, as opposed to signals. It should be noted, however, that Tesla operated a radio-controlled boat in New York City in 1898, and that some believe that his disclosures in 1893 mark the birth of wireless telegraphy.(3)

On a purely historical note, we must also mention that the first wireless telegraphy patent was issued on 20 July 1872 to one Mahlon Loomis, who made use of atmospheric electricity to receive signals using 183 metre long kite-supported antennas on two mountain peaks in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, some 22 kilometres apart. This system was demonstrated in 1866.(4)

The conflicting claims of Marconi in the UK and Popov in the USSR as the inventors of wireless telegraphy are discussed at length by Barrett.(5) He describes the systems used by both, and after considering published information and indirect evidence and claims, concludes that Marconi 'can be named as the inventor of radio communication' Considering all the evidence, there can be no doubt that Marconi, in true entrepreneurial spirit, saw an opportunity for exploiting the fledgling science of wireless telegraphy when many scientists were still captivated by the novelty and the underlying science. Certainly Marconi, starting with his early experiments at the Villa Griffone in Italy in 1894 and 1895, devoted his energies to developing a workable system for the transmission of messages without wires. It is on this that his pioneering reputation is founded.

The technically minded reader is referred to the Institute for Electrical Engineers Conference, held in London in September 1995, which celebrated '100 Years of Radio'.(6)

Wireless telegraphy in Britain at the turn of the century

By 1850 telegraphy on land using the Cooke and Wheatstone single-needle receiver, or the Morse embossing instrument, operated over relatively long distances and had been demonstrated over lines more than 1 600 km in length. The first successful undersea cable across the English Channel was laid in September 1851. In 1855 a telegraph cable had been laid across the Black Sea to the Crimea.(7) Communications between the British Government and General Simpson, Commander of the British Forces in the Crimea, was possible by a combination of undersea and land based cables. (In fact, General Simpson appeared to consider this more of a hindrance than a help as he was continually bothered with minor queries concerning the progress of the war in the Crimea).(8) After many misadventures the first successful trans-Atlantic signals were passed between Britain and North America on 13 August 1858. The cable became unusable during September 1858 for a number of reasons, but not before the British Government had cancelled plans for two regiments to be despatched from Canada for use in India. This is said to have saved the British Government some £50 000 - no mean sum in those days.(9) By 1870 the first regular telegraph unit had been established to maintain telegraph communications for the army in the field. In South Africa this unit took part in several campaigns, including the Zulu War of 1879, and the First Anglo-Boer War of 1880-81.(10) However, communications between headquarters and the frontline still required that messages be conveyed by hand, or by a system of visual signalling.

Against this background it is hardly surprising that there should have been keen interest in the new technology of wireless telegraphy. As early as 14 August 1894 at the British Association meeting in Oxford, the first public demonstration of the transmission of information by wireless telegraphy had been given by Oliver Lodge, Professor of Physics at Oxford.(11) It would, however, appear that Lodge failed to recognise the significance of the achievement and it was left to others, notably Marconi, to capitalise on the potential of the new technology.

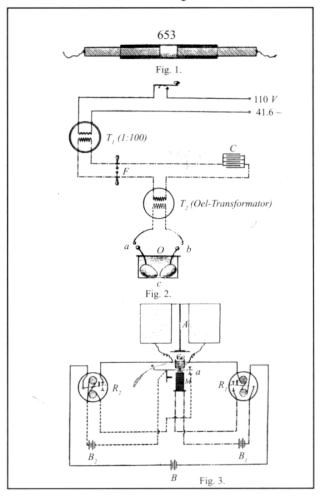

In Austin's paper,(12) he refers to a demonstration of a system to transmit messages without wires organised by Sir William Preece, Chief Engineer of the Post Office, at Salisbury Plain in late 1896. Present in this group was a Captain J N C Kennedy of the Royal Engineers who was to play an important role in the deployment of Marconi's equipment in South Africa at the start of the Anglo-Boer War in 1899. These tests and subsequent demonstrations showed that it was possible to achieve reliable communications over some tens of kilometres using vertical wire antennas 37 metres long, and connected to earth at one end. This distance was later extended to 40 km. The transmitter consisted of the secondary winding of a Ruhmkorff coil (essentially similar to the induction/ignition coil in a motor car, but capable of producing much larger sparks), with the spark gap connected between the wire antenna and earth. A typical spark length was approximately 250 mm, produced by keying the primary coil across a fourteen volt battery of Obach cells using a Morse key. The current drawn was of the order of six to nine amps. The basic transmitter and receiver circuits are shown in Figure 1.(13)

Figure 1: Sketch of a coherer, transmitter and receiver

used in a late 19th century wireless telegraph set

(Source: Zeitschrift für Electrotechnik, Jahrgang XV, Heft XXII, Nov 1897)

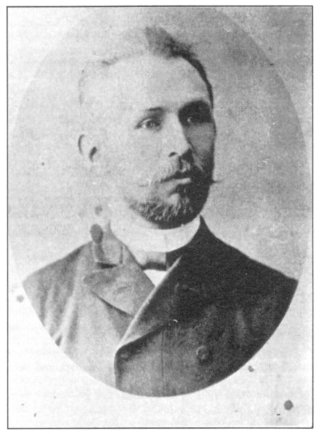

Robert Poole served in the electrical branch of the Royal Engineers during the Anglo-Boer War. He spent two years in the field as a telegraphist, being appointed Telegraph Master at Heidelberg in the Post Office of the newly annexed Transvaal. He served in the First World War with the rank of major. Later, as Chief Engineer of the South African Post Office, he handled the start of broadcasting in South Africa.

Early interest in wireless telegraphy in South Africa

Cape Province

Rosenthal's account of the early days of wireless telegraphy in South Africa indicates that interest was more widespread than that suggested by Baker and Austin. (16) According to his research, Edward Alfred Jennings, born in London in 1872, may have discovered wireless telegraphy independently of workers in Europe and North America. At a young age he applied for a position in the Post Office of the Cape Colony. After two and a half years in Cape Town he was transferred to Port Elizabeth's telephone exchange in 1896. This had been opened in 1882 and was the oldest exchange in South Africa.

In the course of trying to improve on the old microphones using carbon granules, Jennings experimented with metal filings, which he expected would not pack together as the carbon granules did. He fabricated a microphone using a glass tube and some silver filings off a watch chain. In effect he created a coherer similar to that used by Marconi and others for the detection of the Morse radio transmissions. He observed that his experimental receiver responded when an electric doorbell was used. The filings adhered to each other and had to be tapped lightly to loosen them. Even more surprising was the discovery that electric trams passing through a cross-over caused a much louder crackle in his primitive receiver than the doorbell. He observed that this correlated with the spark caused when the trams passed through the cross-over. After he was unable to obtain an explanation for this from various 'experts' in the area, he built a Ruhmkorff coil to generate bigger and 'louder' sparks. Rosenthal describes the construction of this coil in detail.

Using his home-made apparatus, Jennings first succeeded in transmitting signals over a distance of half a mile (800 m) in 1896. Further experiments followed. Shortly after this, reports came through of Marconi's work on Salisbury Plain

In 1898 the Marquis of Graham visited South Africa. He was acting on behalf of Lloyd's of London, which was interested in safety at sea Experimental transmissions were made between Bird Island Lighthouse and the mainland. No doubt encouraged by these experiments, Jennings next erected his transmitter at the lighthouse on the Donkin Reserve. In July 1899 he achieved a distance of eight miles (13 km). Using a strip of wirenetting about a foot (30,4 cm) wide as an aerial, the lighthouse keeper was able to drive a Morse tape machine printer with the received signal. Despite the optimism created by the experiments, further development was stymied by the extremely short-sighted opinions expressed by no less a person than John X Merriman. As late as 1899 trials were again held between Port Elizabeth and the mail steamer Gascon lying three miles (5 km) out in Algoa Bay Rosenthal, who met Jennings in the 1940s, comments that Jennings' work was overshadowed by the events of the time. Surely Jennings must be acknowledged as one of the pioneers of this fledgling technology.

In his book(17) Rosenthal also describes an experiment carried out on the Grand Parade in Cape Town in February 1899 under the supervision of Dr (later Sir) John Carruthers Beattie, who became Vice-Chancellor and Principal of the University of Cape Town. Using equipment imported from Britain, he and other notables demonstrated the use of wireless telegraphy to transmit signals over a distance of 400 feet (120 metres). The shipwreck of the Tantallon Castle on Robben Island further stimulated interest in the use of wireless telegraphy for safety at sea. An agreement was reached between the Cape Government and Lloyd's of London to establish wireless telegraphy between Dassen Island and Robben Island, as well as between Bird Island and Port Elizabeth. It was further reported that ships of the Union-Castle Line would be equipped with this apparatus, enabling them to communicate with Dassen Island from a distance of 186 miles (300 km). This decision was to be rescinded in August of 1905.

The outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War a few months later and the subsequent confiscation by the British forces of wireless telegraphy equipment made by Siemens and intended for use in the Transvaal Republic, or Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR), now links us directly to surprising events in the ZAR prior to the war, This section of the article would not be complete without mentioning that in 1902 the Cape Parliament amended the Electric Telegraph Act of 1861 to take account of wireless telegraphy. The first wireless licences were also introduced in the Cape of Good Hope Colony. Both were world firsts.(18)

The Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR)

Research at the State Archives in Pretoria uncovered a rich trove of material relating to early interest in wireless telegraphy in the ZAP.(19) The main actors in the drama that was about to unfold there in wireless telegraphy were Paul Constant Paff (Figure 2) and C K van Trotsenburg (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Lt Paul Constant Paff

Figure 3: The ZAR Telegraphy Department, 1896.

Van Trotsenburg is shown seated.

The Field Telegraph Department was established by a vote in the Volksraad in May 1890, and would form part of the ZAR Staatsartillerie.

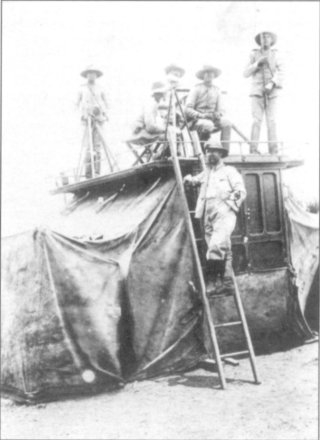

Paff's contract lapsed at this time and he was offered and accepted a commission in the Staatsartillerie. He trained fifteen men in the skill of Morse telegraphy. At the completion of their training, the men were able to send and receive messages in Morse by means of telegraph, heliograph, lamp, and also by means of flags.(20) Figures 4 and 5 show the Field Telegraph Company in the field.

Figure 4: Signallers of the Field Telegraph Department of

the ZAR before the war. Lt Paff is standing on the ladder

Figure 5: Lt Paff (seated) with signallers outside the

Staatsartillerie Headquarters in Potgieter Street, Pretoria

'On account of the aforementioned and in view of high costs, I would not recommend the laying of an underground connection between the Artillery camp and Daspoortrand, but would suggest the erection of an overhead line, to be worked with an ordinary telegraph or telephone instrument or perhaps with both.

For distances of about 6 miles [9,6 km] telegraphic communications can be exchanged without wire. At present, experiments are being conducted in Furope on a large scale by Military Powers, and it appears to me that lately such improvements have been made to those instruments used therefore, that the system would probably answer well for the forts.

I would suggest that I communicate with manufacturers and in case of satisfactory information being received tu order one set of instruments for trial.

The costs connected therewith are comparatively low.'

This is not, however, the first official indication of an interest in wireless telegraphy. On 28 February 1898, a few days earlier, van Trotsenburg had taken the initiative to write as follows to Siemens Bros in London:(23)

'Gentlemen,

A certain place "A" in a valley is surrounded by hills.

I wish to correspond telegraphically without wires

between this place "A" and those hills as marked in the

margin 1, 2, 3, 4 ... Are there any difficulties[?] If so,

which? If not, can you supply us with the necessary

instruments complete[?]

If you can supply them, please send one set (two

instruments) for taking a trial, for use either between "A"

and 1, or 1 & 2, etc; the most exhaustive directions for

use should accompany the instruments.

Of course we require the best known instruments of this class, with all the improvements which have since been introduced in the instruments of Marconi. We will be pleased to learn by return of post what you can do for us. In case you send the instruments, please send them via Durban.

If the trial [is] in any way successful, we will give you a further order. Please indicate certain cablewords in order to place us in a position to give you an order by cable.

I have the honour to be, your obed't servant,

C K van Trotsenburg

General Manager of Telegraphs'

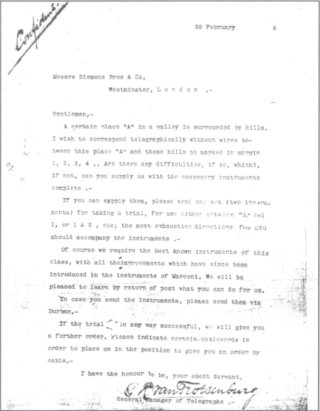

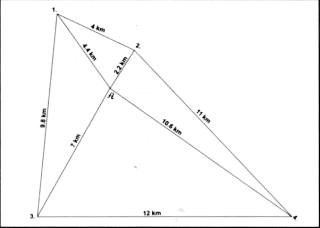

A copy of this letter and the map appear in Figures 6 and 7. Of interest is the fact that van Trotsenburg appears to have been well versed in wireless telegraphy and that communication by cable to Great Britain appears to have been common practice.

Figure 6: A copy of van Trotsenburg's letter to Siemens Bros

in London, requesting information on wireless telegraphy

Figure 7: A copy of the illustration accompanying van

Trotsenburg's letter (after the original sketch)

The reply from Siemens is dated 26 March 1898 and refers to the technicalities of establishing a wireless telegraphy link, and some general features of the equipment. It also appears that discussions were held by Siemens with the Marconi company, which held the patents. The company declined to sell equipment outright, but was prepared to lease it, and wanted to know the identity of the potential client.(26)

On 20 April 1898, L W J Leyds, the State Secretary of the ZAR, instructed van Trotsenburg in writing to investigate the supply of wireless telegraphy equipment.(27) Van Trotsenburg corresponded with Siemens and Halske in Germany,(28) as well as a French company in Paris, Societe Industrielle des Telephone, whose reply is dated 16 June l898(29). The French company provided a detailed quote for their equipment.

From a further reply(30) of Siemens Bros in London it was clear that the Marconi company intended to maintain tight control of their equipment. Effectively the client would only be able to use the equipment under a lease arrangement, and Marconi would install and maintain the said equipment. Siemens Bros also refer to contacts with Prof Oliver Lodge on the matter. On 21 June 1898, Siemens and Halske's South African agents made an offer to supply sufficient equipment for five installations at a total cost of £485.(31) This was signiflcantly lower than the £9 000 cost of installing a telegraph cable, referred to earlier.

There now follows a substantial gap in the record of

correspondence. It is difficult to imagine that, with this

level of interest, communications should have ceased. It

is tempting to speculate that in all likelihood there must

have been a steady exchange of correspondence, culminating

in June and July 1899 with a visit by van Trotsenburg to

Europe to discuss matters at first hand with potential

suppliers. Amongst the companies he visited was the

Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company in London, who,

on 1 July 1899, offered to supply van Trotsenburg with

five sets of equipment at a total leasing cost or royalty of

slightly more than £95 per complete set per year.(32)

By then it must have been very clear that war with

Great Britain was unavoidable. Accordingly, on 24 August

1899, van Trotsenburg placed an order for six sets of

spark wireless telegraphy instruments with Siemens and

Halske in Berlin.(33) This must surely have been one of

the earliest orders (if indeed not the first) for wireless

telegraphy equipment and bears quoting in full:

'With reference to your telegraphic communication of

20th inst stating:-

"we can deliver three stations within fourteen days, the

rest within one month. The price at Berlin, one hundred

and ten pounds each and a pole of forty metres will be

required to work out to a distance of fifteen KM [sic].

We will then guarantee good working up to this distance,

supposing there is good management and excepting

atmospheric interruption":-

and adverting to our personal conversation of yesterday, I now have the honour to inform you, that we accept your offer to supply 3 "spark-telegraph instruments" complete at £110 each at Berlin, payment to be made after the instruments have been erected in Pretoria and found satisfactory and in accordance with your guarantee. If these instruments prove satisfactory and answer our purpose, we are prepared to place an order for further 3 complete instruments at the same price and conditions a aforementioned, the six instruments to be forwarded from Berlin as stated in your wire:-

I would further request your attention to the necessary

poles for these instruments according to our conversation

and especially concerning the following:

(1) Material to be of light weight.

(2) A simple way of erecting and breaking same down,

perhaps your firm already has a simple method, if not, to

enable us by a simple way of construction to lower an

erected pole.

We should require the poles to be delivered with the instruments. Enclosed please receive the Electrical Engineer London edition, No 14,1898, page 420.

In case we do not require to use the complete length of the pole and as in such case I would not like to use the pole higher than necessary, I trust that the pole will be constructed in such a way to enable us to do away with certain parts thereof if necessary.

I would further request you to duplicate all such parts of the instruments subjected to hard wear and also those liable to breakage.'

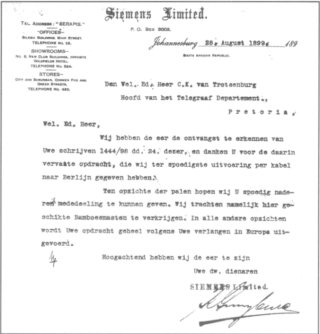

Acknowledgement of the order by Siemens Ltd in

Johannesburg, dated 28 August 1899, is shown in Figure 8,

and reads:(34)

'We have the honour to acknowledge receipt of your

letter 1444/98 of 24th inst and thank you for your order

contained therein, which we have cabled to Berlin for

immediate execution.

With regard to the poles we hope to be able to give you

further information shortly.

We are trying to obtain suitable bamboo poles here. In

all further respects your order is being executed in

Europe in accordance with your request.'

Figure 8: Acknowledgement by Siemens Ltd, Johannesburg,

of van Trotsenburg's order for wireless equipment

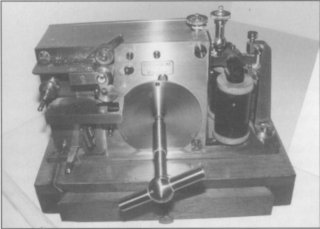

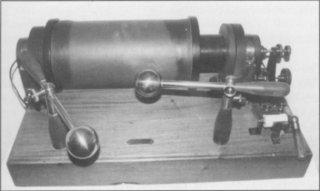

Details of the fate of the wireless telegraphy equipment destined for the Boer forces are given in the accounts by Ploeger and Botha, Kennedy, Austin, and Rosenthal.(37) The equipment was cannibalised by the British Forces for spare parts for the Marconi system being deployed in South Africa. The remaining Siemens equipment was sold off after the war by the Quartermaster General, and purchased by F G T Parsons. Rosenthal was able to talk to him and he confirmed demonstrating wireless telegraphy using this equipment. Eventually some of the equipment made its way to the War Museum in Bloemfontein, which has a restored Ruhmkorff coil transmitter, receiver and Morse inker. These are shown in Figures 9, 10 and 11. The South African Corps of Signals Museum has a restored receiver.

Figure 9: The Siemens receiver

(Photo: By courtesy of the War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein)

Figure 10: The Morse inker for the Siemens receiver

(Photo: By courtesy of the War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein)

Figure 11: The restored Marconi Ruhmkorrf coil transmitter

(Photo: By courtesy of the War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein)

British use of wireless telegraphy during the war

'Failure' in the Army

Comprehensive details of the British use of wireless telegraphy during the war may be found in the reports of Austin and Fordred,(38) What follows is based on their reports, with a few additional references.

At the outbreak of war, Marconi persuaded the British War Office that wireless telegraphy would be useful in ship-to-shore communications in order to regulate shipping traffic in Durban and Cape Town, where the steady flow of troopships was causing massive congestion and delays in the harbours.(39) Persuaded by this suggestion and the success of trials of Marconi's system during the naval manoeuvres earlier in 1899, the War Office agreed to hire five wireless sets and operators on a six-month contract, with effect from 1 November 1899. The equipment was to be used to control shipping at the ports.

By the time Marconi's engineers, Bullocke (in charge), Dowsett, Elliott, Franklin, Lockyer and Taylor, arrived in Cape Town on 24 November 1899, they found that the original agreement had been changed and they were invited to volunteer for active service in the field. The men were prepared to do so, but the equipment, which had been designed and tested for shipboard use, had to be installed in wagons for use on land. This may well have been the first mobile wireless system! Captain I N C Kennedy, who had been present at Marconi's early demonstrations and knew him, was appointed to assist Bullocke and his men. Figure 12 shows some of the men involved in this work.

The battery power supplies and jelly accumulators were secured to the bottom of a wagon, along with the spark transmitter. The Morse key was to be operated at the back of the wagon to keep the operator away from the spark, which could be as long as 30 cm according to the detailed quotations of equipment referred to earlier. A successful demonstration of the equipment was held at the Castle in Cape Town in early December, and was described by Kennedy as a success.(40) At this time, Kennedy was also able to view the confiscated Siemens equipment. He was critical of the fact that the sets were not enclosed in metal, thus affecting their suitability for operational use, but nevertheless took the oscillators and Morse keys. The British equipment had no masts, as it was originally intended for shipboard use, and antennas could have been rigged easily. The steel masts which accompanied the Boer equipment were abandoned, presumably because there was insufficient time available for their evaluation. The British equipment was to be operated using bamboo masts. This decision was to be the root cause of problems experienced later.

The equipment was to be deployed around De Aar, the railhead for the dispersal of the British forces. The wireless telegraphy sets were intended for communications between various British columns operating in the area. At this stage it became clear that the wagons used for the mobile installations were unsuitable for the task.

Figure 12: Royal Engineers/Marconi Company Wireless

Section at De Aar encampment, South Africa, 1899

(Photo: By courtesy of GEC-Marconi)

The bamboo poles soon began to split in the dry, arid conditions prevalent in the Karoo where Marconi's engineers were deployed. Kites and balloons, as shown in Figure 13 and the first illustration in this article, were used in an attempt to provide the spark transmitters with a suitable length antenna - the length being crucial for tuning the system. Three of the sets were sited at the towns of Orange River, Belmont and Modder River. An additional station was established at Enslin, some 27 km from Modder River, to provide advance warning of a possible Boer attack. Establishing communications between the various sites using poles or kites proved to be difficult. In addition, the high level of atmospherics from thunderstorms caused considerable interference at the receivers. By the end of December 1899, wireless contact had been established between Orange River and Modder River, a distance of some 80 km, via a manually operated relay station at Belmont.

Owing to adverse weather conditions, the Marconi equipment remained unserviceable for three of the six weeks which were spent on evaluating the system in the field. Naturally, Marconi defended the system and his operators against criticism for failing to establish wireless communications. At a meeting of the Royal Institution on 2 February 1900, he made a fortuitous tactical blunder by criticizing the local military authorities for not making proper preparations. The light bamboo poles which had been selected for use had not been up to the task and had broken due to drying out. Taking umbrage at this criticism, the Director of Army Telegraphs instructed the sets in the field to be dismantled immediately. Two further sets, which had been sent to accompany General Buller's forces in Natal, were also withdrawn from service.

Figure 13: George Kemp, formally Marconi's

Chief Assistant, with a Baden-Powell kite

(Photo: By courtesy of GEC-Marconi)

Success in the Navy

The successful trials in the Royal Navy during the manoeuvres of 1899 prior to the war had no doubt sensitised the naval authorities to the potential usefulness of Marconi's system. The five wireless telegraphy sets which were withdrawn from active service with the British Army following Marconi's 'fortuitous blunder' (referred to above), became available fur use by the Royal Navy, which requested the equipment to support the naval blockade of Delagoa Bay. By March 1900, these five sets had been installed on the cruisers HMS Dwarf, Forte, Magicienne, Racoon and Thetis. Thetis was the first vessel to be equipped with wireless apparatus under wartime conditions.(41)

As was to be expected, the ships proved to be ideal platforms for the equipment. Extended masts and the good conductivity of seawater greatly improved the performance of the telegraphy sets. The operational area and effectiveness of the ships could be drastically increased as they no longer needed to maintain sight of each other in order to exchange signals. Furthermore with the Magicienne in Delagoa Bay providing a relay to a telegraph landline speedy communication was possible between the ships at sea and the operational headquarters for the Navy in Simon's Town, some 1 600 km away. A communications range of 85 km was obtained on 13 April 1900. There is also an unsubstantiated claim of a signal transmission over a distance of 460 km.

By November 1900 the nature of the war in South Africa had changed. It had become a guerrilla war and the British had begun to apply a scorched earth policy.(42) There was no further need for wireless communications in the Navy. The significant point, however, is that between the successes achieved in wireless trials during the naval exercises in 1 899 and the undoubted success of the use of wireless under operational wartime conditions, the Navy was convinced of the viability of Marconi's system. A decision was taken to equip 42 ships and eight shore stations around Britain with wireless telegraphy equipment by the end of 1900.

Austin provides an interesting technical perspective on the problems experienced by the British Army with the use of Marconi's system under operational conditions in South Africa.(43) By weighing the evidence provided by operations on land and at sea, it is reasonable to conclude that important factors which contributed towards the lack of success around De Aar included the problems associated with elevating the antennas to suitable heights and the failure of the masts; climatic conditions, including the frequency and severity of thunderstoims; and poor earth conductivity.

Final comments

It is intriguing to think that, but for the timing, the ZAR could have had a wireless telegraph network connecting the forts around Pretoria at the outbreak of war. As far as can be established, van Trotsenburg accompanied President Paul Kruger to Machadodorp, site of the ZAR Government towards the end of the war, and subsequently returned to the Netherlands(44) Paul Constant Paff is reported to have maintained close links with the military after the war and to have acted as adviser to the South African Government. His papers are housed in the Archives of the Parliament of South Africa.(45)

The willingness of Marconi to supply the ZAR with wireless telegraphy equipment adds an interesting side-light to the story.(46) The British Army's experiences with the operational use of wireless telegraphy equipment appears to be fairly typical of new and sophisticated equipment in the initial stages of deployment, even today. There can be little doubt, however, that the experience gained during the Anglo-Boer War served the Marconi company well in the further development and refinement of the equipment.

The importance of this early application of wireless telegraphy equipment in the development of modern radio communications has been recognised by the Institution of Electrical and Electronic Engineers with the declaration of an IEEE historical milestone. The proposed citation for the first operational use of wireless telegraphy reads:

'The first use of wireless telegraphy in the field occurred during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). The British Army experimented with Marconi's system and the British Navy successfully used it for communication among naval vessels in Delagoa Bay, prompting further development of Marconi's wireless telegraph system for practical uses.'

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the many useful exchanges of ideas and information with (and constructive comments by) my friends and colleagues Dr Brian Austin of the University of Liverpool, and Mrs Lynn Fordred, Curator at the SA Corps of Signals Museum. They have greatly extended my own meagre knowledge of the facts and sequence of events in this fascinating history of the first use of wireless telegraphy under operational wartime conditions. The library staff at the State Archives were also most courteous and helpful in locating the original files on which much of the local history is based. Sincere thanks and appreciation are also due to the War Museum of the Boer Republics for permission to use photographs of the Siemens and Marconi equipment exhibited there. The author was allowed to inspect and handle the artifacts personally during a visit to the Museum in October of 1998.

References

1. B A Austin, 'Wireless in the Boer War', IEE International

Conference: '100 Years of Radio', 5-7 September 1995 (Savoy

Place, London, IEE Conference Publication No 411), pp 44-50;

D C Baker and B A Austin, 'Wireless telegraphy circa 1899:

The untold South African story', IEEE Antennas and

Propagation Magazine, Vol 37, No 6, December 1995, pp 48-58;

L L Fordred, 'Wireless in the Second Anglo Boer War 1899-1902',

Transactions of the SAIEE, Vol 88, No 3, 1997, pp 61-71.

2. J S Belrose, 'Who invented Radio?', Letter to the Editor, The

Radio Science Bulletin, No 272, March 1995, pp 4-5.

3. R L Riemer, 'About Tesla's contribution to the invention of

Radio', The Radio Science Bulletin, No 272, March 1995, p 5.

4. Belrose, 'Who invented Radio?', pp 4-5.

5. R Barrett, 'Popov versus Marconi: The centenary of Radio',

GEC Review, Vol 12, No 2, 1997, pp 107-112.

6. Austin, 'Wireless in the Boer War', pp 44-50.

7. B S Finn, Submarine Telegraphy: The Grand Victorian

Technology (National Museum of History and Technology,

Smithsonian Institute, 1973).

8. Fordred, 'Wireless in the Second Anglo Boer War 1899-1902'

pp 61-71; N F B Nalder, The Royal Corps of Signals (Royal

Signals Institution, 1958), p 11.

9. Finn, Submarine telegraphy - The Grand Victorian Technology

10. Fordred, 'Wireless in the Second Anglo Boer War 1899-1902', pp 61-71.

11. P Rowlands and J P Wilson, Oliver Lodge and the invention

of Radio (PD Publications, 1994).

12. Austin, 'Wireless in the Boer War', pp 44-50.

13. 'Telegraphie ohne draht', Zeitschrift für Electrotechnik,

Jahrgang XV, Heft XXII, 15 November 1897, pp 264-5.

14. E Rosenthal, You have been listening ... The early history

of Radio in South Africa (Published by the South African

Broadcasting Corporation to mark the 50th anniversary of

broadcasting in South Africa, 1974), pp 1-11.

15. Private communication with B A Austin.

16. Baker and Austin, 'Wireless telegraphy circa 1899: The untold

South African story', pp 48-58.

17, Rosenthal, You have been listening ... The early history of

Radio in South Africa, pp 1-11.

18. Rosenthal, You have been listening ... The early history of

Radio in South Africa, pp 1-11.

19. Bakerand Austin, 'Wireless telegraphy circa 1899: The untold

South African story', pp 48-58.

20. Fordred, 'Wireless in the Second Anglo Boer War 1899-1902', pp 61-71;

South African Corps of Signals (SADF Documentation Services,

Publication No 4, 1975), p 6.

21. J Ploeger, assisted by H J Botha, The Fortification of

Pretoria: Fort Klapperkop - Yesterday and Today (Military

Historical and Archival Services, Publication No 1,

Government Printer, Pretoria, 1968).

22. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa.

Report by C K van Trotsenburg to L W J Leyds, State

Secretary, ZAR, on telegraph communications between

military camps and fortifications around Pretoria, 2 March

1898.

23. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa. Letter

from C K van Trotsenburg to Messrs Siemens Bros and Co in

Westminster, London, UK, stating wireless telegraphy

communications problem, 28 February 1898.

24. For example, 'Telegraphic ohne draht', pp 264-5.

25. Summaries in the State Archives are of articles in the

Electrotechnische Zeitschrift (1897) and the Electrical Engineer

(1897). An issue of The Electrical Review, 19 August 1898,

includes an article describing Marconi's demonstration

between the Royal yacht Osborne and Osborne House over a

period of ten days.

26. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa. Reply

from Siemens Bros and Co, Westminster, London to C K van

Trotsenburg, dated 26 March 1898.

27. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa. Letter

from L W J Leyds, State Secretary of the ZAR, to C K van

Trotsenburg, instructing him to proceed with the investigation

of supplying wireless telegraphy equipment, 20 April 1898.

28. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa: Letter

from C K van Trotsenburg to Siemens and Halske AG, Berlin,

requesting whether they could supply wireless telegraphy

equipment, dated 23 April 1898; letter from Siemens and

Halske, Berlin, to van Trotsenburg, advising him to expect a

reply from their South African agents, dated 25 May 1898;

letter from C K van Trotsenburg to Siemens Bros, London,

requesting more details to their reply of 26 March 1898, dated

23 April 1898.

29. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa: Letter

from Societe Industrielle des Telephones, Paris, to C K van

Trotsenburg, providing a detailed quote of the French

equipment, 16 June 1898.

30. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa. Reply

from Siemens Bros, London, to van Trotsenburg's inquiries

dated 23 April 1898.

31. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa. Reply

from Siemens and Halske's South African agents in Johannesburg

(following the letter of 26 March 1898 from Siemens and

Halske in Berlin to C K van Trotsenburg) to van Trotsenburg,

21 June 1898.

32. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa.

Letter from the Wireless Telegraphy and Signal Company Ltd, London,

confirming discussions with van Trotsenburg on 30 June 1899

and their willingness to supply wireless telegraphy equipment

to the ZAR, 1 July 1899.

33. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa.

Order placed by C K van Trotsenburg with Messrs Siemens Ltd,

Johannesburg, for six wireless telegraphy sets, Document No

1444/98, 24 August 1899.

34. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa.

Acknowledgement by Siemens Ltd, Johannesburg, of C K van

Trotsenburg's order placed with them on 24 August 1899,

dated 28 August 1899.

35. File NAB291035488, Source CSO, Vol No 2583, Ref C4481

1899, Natal Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Letter

from the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony to the Prime

Minister of Natal, requesting Customs to seize wireless

telegraphy equipment believed to be on board the Dunottar

Castle, 3 November 1899.

36. J N C Kennedy, 'Wireless Telegraphy - Marconi's System',

extracts from the Proceedings of the Royal Engineers'

Committee, 1901, pp 155-9.

37. Ploeger and Botha, The Fortification of Pretoria: Fort

Klapperkop - Yesterday and Today; Kennedy, 'Wireless

Telegraphy - Marconi's System', pp 155-9; Austin, 'Wireless

in the Boer War', pp 44-50; Rosenthal, You have been listening

The early history of Radio in South Africa, pp 1-11.

38. Austin, 'Wireless in the Boer War', pp 44-50; Fordred,

'Wireless in the Second Anglo Boer War 1899-1902', pp 61-71.

39. Document No 181, GEC Marconi Archives, Chelmsford,

Essex, England. Memorandum Sent by the Marconi Company

to the British War Office.

40. 'Wireless Telegraphy - Marconi's System' REC Extracts,

1900, p 125.

41. A Hezlet, The Electron and Sea Power (Peter Davies,

London, 1975).

42. E Lee, To the Bitter End: A photographic history of the Boer

War 1899-1902 (Penguin, 1985), p 163. Memorandum

released in Pretoria on 21 December 1900 by Lord Kitchener.

Circular Memorandum No 29 from the Archives of the

Military Government, Pretoria.

43. Austin, 'Wireless in the Boer War', pp 44-50.

44. Brig J H Pickard (compiler), 'Col S F Pienaar's Boer War

Diary - Part 2', Militaria, Vol 23, No 4, 1993, pp 1-15.

45. Ian Uys (ed), Military History's Who's who 1452-1992

(Fortress, 1992).

46. File TLD No 1, State Archives, Pretoria, South Africa. Letter

from The Wireless Telegraphy and Signal Company Ltd.

London, confirming discussions with C K van Trotsenburg on

30 June 1899 and their willingness to supply wireless

telegraphy equipment to the ZAR, 1 July 1899.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org