The South African

The South African

Introduction

An enquiry by Dr W Bizley of the University of Natal regarding the sinking in 1943 of U-Boot 97 near Madagascar alerted the author to the realization that the exclusive secret service rendered to the Royal Navy by South Africa during the Second World War (1939-1945) had not been documented in this country. Furthermore, it seems that there is a general unawareness of both the extent of the submarine war off the coast of South Africa and the significant contribution made towards their destruction by a small group of dedicated men and women. As possibly the sole survivor of that group, the author felt obliged to record his reminiscences of the activities of the group in this article and hopes that, by doing so, readers who may be in possession of more accurate information might come forward.

Essentially, the following article deals with the use of high frequency direction finding (or HuffDuff), a rather technical system, which nonetheless served its purpose, and very successfully too, much to the chagrin of the U-boat commanders who never found out how they were discovered! This document deals only with the location of German U-boats by means of high frequency direction finding and does not cover the subsequent action initiated through the location of the target by this means. The article covers the period 1939/40 (when sites for the direction finding stations in South Africa were being selected) to the middle of 1942, after which the author left the country.

While the interpretation of the essence of coded U-boat transmissions might appear to be an easy matter, it required trained and experienced personnel. The Head of the Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy, which controlled this activity, was situated in the Admiralty in London, while those concerned with the decoding or deciphering of intercepted radio messages were mostly civilians housed in a very beautiful old English home called Bletchley Park - a very hush, most secret establishment.

A coding/decoding machine called the Enigma was used extensively by the Germans and messages coded by it were impossible to decode. The acquisition of an Emgma machine by the British Navy was one of the most critical events of the war and the incredible story of the Enigma is presented in a book by Ronald Lewin, entitled Ultra goes to war, published by Arrow Books Ltd, London (See also the article entitled The Enigma machine and the "Ultra" Secret', by Colin Dean, which begins on p 1 of this issue of the journal).

Especially in the early days of the war, the U-boats were required to report directly to their home base, even in the event of the sighting of a target (particularly a convoy). They did not appear to have had the freedom of making their own decisions. Later, when hunting in packs, this method of communication enabled the home base to coordinate the attack and bring in additional boats where necessary. While there have been reports of 'chats' between the U-boats, the author is sceptical of this because the coding and decoding process was complicated (and the Enigina notoriously slow) and he never personally experienced U-boats communicating with each other in plain language. However, he does concede that, towards the end of the war, the restrictions may have been modified or removed.

Those listening in on U-boat transmissions learned to recognize when a U-boat had sighted a target. In such an event, the transmission would begin with the Morse Code 'dot dot dash dot dot' (..-..) When this signal or another was intercepted, a whole train of events was initiated, which will be discussed below. The purpose of those responsible for intercepting the U-boat transmissions was to obtain bearings on the transmissions, and not to attempt to decode the messages, this latter task being carried out by the personnel at Bletchley Park.

The establishment of a high frequency direction finding unit in Simon's Town, South Africa

In the last quarter of 1939, a Royal Navy officer, Lt J S Bennett, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (United Kingdom), arrived in South Africa from England. His mission was to seek the assistance of the South African authorities in establishing an organization here which could be used by the Royal Navy to locate German U-boats at sea anywhere in the world. In so doing, the South Africans would be protecting their own interests and the safety of ships operating in South African waters. Secrecy was of paramount importance in preventing local German intelligence agencies from becoming aware of the existence of this organization.

Judging by the facilities which were made available to him, it would appear that Lt Bennett had access to the highest level, probably even to Prime Minister Smuts himself, who was known to have had a very high regard for the Royal Navy. (Smuts once said that the greatest force for peace in the world was not the League of Nations, but the Royal Navy.) General Hertzog, too, acknowledged the Union's debt to the Royal Navy and, whilst he and Smuts could not agree on whether or not South Africa should remain neutral during the war, they did concur that the Royal Navy should continue to use Simon's Town.

Very soon the search began for suitable personnel who had been cleared by Security and who could read Morse Code. In addition, technically suitable personnel who could install the equipment from England and others who could recommend where it should be installed had to be found.

It was decided that the controlling unit would be set up in the Admiral's Office, Simon's Town, and the author moved in as the first occupant! Lt Bennett had arrived with information about U-boat transmitting frequencies and the times when these were expected to change. The author was required to learn as much as possible about methods of radio interception, the techniques of taking bearings, controlling the entire operation, and about the equipment which was being installed, how it was going to work, what could be expected from it, and how to deal with the information which would be presented. The author was also made responsible for training the operators in these procedures; apart from Lt Bennett, nobody in South Africa had any knowledge of the facility. Although the author had some experience as a radio ham (an amateur radio operator) in his private life and as a Petty Officer Telegraphist in the RNVR (South Africa) with some technical training and knowledge, nothing prepared him for this new experience.

The author had spent many hours in his private life listening, with a pair of headphones clamped to his ears, to one frequency on one receiver. At Simon's Town, he was provided with three radio receivers - one connected to a loudspeaker and the other two to a set of headphones with one earphone connected to each. It was thus possible to monitor three frequencies simultaneously - a necessity as no other naval operators were available and it was easier to train one man (the author) and then to have him train others.

U-boats usually surfaced at night to refresh the air in the boat and to recharge their batteries. They also utilized this time to transmit and receive radio signals. Thus, in Simon's Town, most of the listening occurred at night.

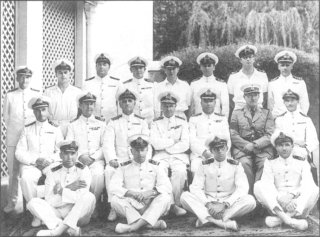

Rear-Admiral D A Budgen, CB, Flag Officer-in-Charge,

South Africa, 1939-42, with his staff at Admiralty House,

Simon's Town. Lieutenant J S Bennett is sixth from left, back row.

(Photo: By courtesy of the SA Naval Museum, Simon's Town.)

High frequency direction finding was a complicated process. For the sake of making it easier to understand, some sections of the operation described below have been simplified.

Let us accept that there was a receiving station in Simon's Town, which controlled the operation, and that there were at least two radio direction finding (D/F) stations within the borders of South Africa, all manned and ready, with the necessary communication links in place. The operators at Simon's Town and at the D/F stations were all listening to frequencies provided by Simon's Town. (Occasionally, one or more of the D/F stations would hear a signal and take a bearing on it without a prompt from the station at Simon's Town, which may not have heard it.)

In Simon's Town, let us assume that the operator was listening to three frequencies, say 'A', 'B' and 'C', when he heard a U-boat commence a transmission on 'C'. He would then telephone the D/F stations and instruct them to take a bearing of the signal on 'C'. (However, it is possible that such a bearing may already have been taken by a D/F station listening in on the frequency.) The operator in Simon's Town would then await the bearings and, once he had received them from the D/F stations, he would lay them off on the chart. The intersection of the bearings on the chart would indicate the possible area from which the transmission originated and, thus, the possible location of the U-boat.

The above information would then be sent to the Commander-in-Chief's Operations Centre, where it would be added to a plot recording all shipping movements. At the same time, the bearings would be reported to the Admiralty in London for collation with all the bearings sent from other sources and, in the normal course of events, the Admiralty might then have sent a signal to ships operating in the vicinity and, where necessary, to the commodores of convoys, advising them of the presence of a U-boat in their area, thereby enabling them to take the necessary steps.

British ships were under the strictest orders never to use their radio sets for transmitting. Absolute radio silence was the order, except in extreme emergencies. On the other hand, German shipping seemed to show a total disregard for the need to restrict radio transmissions indicating that they assumed it to be impossible to take reliable bearings of high frequency transmissions.

During the early part of the war (1940-1941) it became clear, when listening to U-boat radio signals in South Africa that the 'old school' of German naval radio operators had individual methods of transmitting Morse Code. It therefore became possible to identify individual U-boats by the 'handwriting' of its radio operator. Thus, the movements of a particular U-boat could be traced on a chart - a fascinating but unproductive exercise! As more U-boats were lost during the course of the war, resulting in a frantic build-up of new boats, the nature of Morse Code transmissions changed from the recognizable 'fist' to a less individual and more machine-like transmission, either because operators may have been trained on machines or because machines were being used to send the messages. The Germans also started to fit snorkels to their U-boats, which, it was believed, contained the aerials from the radio sets. For some technical reason, bearings taken on subsequent transmissions became less reliable and it became more difficult to locate the U-boats with the same degree of accuracy as earlier in the war. However, progress had been made with the British ship-borne HufDuff equipment, which enabled ships at sea to locate U-boats with some accuracy and this is believed to have contributed greatly to the war against the U-boats, reducing their pack-hunting successes and causing havoc amongst them.

How did high frequency direction finding work?

In non-technical terms, high frequencies have been used for a long time in transmitting long-distance radio broadcasts across the world. This could not be achieved using medium frequency radio waves, which travel along the surface of the ground and are absorbed by the earth or sea .This type of wave weakens the further it travels. However, from the point of view of taking radio bearings, it has proved invaluable in its accuracy and it is used extensively today for that purpose. High frequency waves (also known as short waves), operate differently, spreading out, some travelling along the ground, which are soon lost, and others travelling up to the ionosphere (an atmospheric level consisting of a number of layers, like blankets). From the ionosphere, these waves are reflected back to the earth and, on striking the earth, some are again reflected back to the ionosphere and so on. In this manner, they are spread around the globe, becoming weaker the further they travel and eventually fading out, after having travelled great distances. Short waves enable South Africans to listen to the BBC, Moscow and other famous radio stations around the world.

Unfortunately, the ionosphere is not a stable reflector of radio signals. Unlike the surface of a mirror, which reflects at a consistent angle, the ionosphere resembles the surface of the sea and the layer is always moving, even on a calm day. This means that a signal from a U-boat, reflected from the ionosphere, would not necessarily strike the earth at the same angle at which it struck the ionosphere, resulting in an apparent change in the bearing of the U-boat's transmission. Furthermore, a signal reflected from the ionosphere often arrived back on earth in such a way that it could not be heard by the listener - the result of 'skip distance', which meant that a signal could sometimes be heard at one station and not at another, only kilometres away.

The nature of the high frequency waves presented an enormous problem to those attempting to track down a U-boat. At the time of the outbreak of the war, Naval Intelligence knew some of the frequencies used by the U-boats and, as the war progressed, more and more frequencies became known, to such an extent that, in South Africa (and elsewhere), operators were advised in advance to expect changes made by the Germans and where to look and listen. The Royal Navy, accepting that inaccuracies were possible in reading the bearings of high frequency transmissions, set up direction finding apparatus in as many different areas as possible in order to obtain numerous bearings on each transmission. Theoretically, more bearings should mean greater accuracy, but this was not always the case in practice.

South Africa's contribution

South Africa was considered to be a very well placed geographical location for high frequency direction finding, thought to be capable of providing excellent coverage of the Atlantic and Indian oceans and of taking bearings on transmissions sent out both far away from and close to her coastline.

It was envisaged that two D/F stations would be installed in South Africa, one at Smith's Farm near Cape Point and the other in Natal near Overport. Selecting the actual site presented a problem as the terrain had to comply with stringent requirements which would ensure that bearings taken from there would not be influenced by magnetic fields in the ground. A third station was also to be erected, but the author could not recall its site - possibly near Bloemfontein, Bulawayo (in Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe) or Maun (in Bechuanaland, now Botswana).

The stations, once established, had to be manned on a 24-hour basis by personnel who knew how to read Morse Code and who had to be of the highest integrity as they would be involved with intelligence work, the nature of which was never to be divulged. These men and women also had to be prepared to spend lonely days and nights at remote D/F stations and to travel quite some distance to arrive there. Mr H M Trainor of the Post Office was made responsible for training the personnel on the new equipment and he also supervised the technical aspects of the installation of the equipment. To fulfil these requirements, the Postmaster provided a group of highly skilled telegraphists of whom the author was very proud. They worked for a long time with the author and, later, his successors and became superbly efficient at their job. The Postmaster also supplied the telephone connections to the D/F stations, which were required to be quite different to those provided to the ordinary subscribers. (It should be borne in mind that, in 1940, telephones had handles which had to be turned in order to attract the attention of the operator, who answered and then inserted a cable with a plug on the end into the number which was required. Trunk calls had to be booked and then the caller had to wait for the connection to be made.) The entire direction finding operation depended on speed, as U-boat transmissions did not last long and the D/F stations had to be contacted immediately and simultaneously so that the relevant frequency could be communicated to the stations and, if necessary, the signal could be heard on the telephone by both stations at once. It was quite an order, but it was achieved successfully.

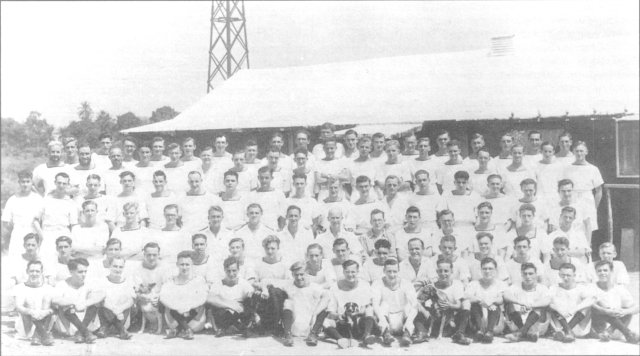

Lt N A Stott and the men, of the Aberdeen W/T Station, Freetown, Sierra Leone, l January 1945

(Photo: By courtesy of the SA Naval Museum, Simon's Town)

In the Simon's Town office, there was also an ordinary telephone with a handle. A special arrangement allowed a radio signal from any of the three receivers to be placed on the telephone line, thus enabling the D/F stations to hear the signal on which they were to take a bearing. While the author is unaware of the exact arrangements of the telephone exchanges, he remembers that a turn of the handle alerted the telephone operator, who then immediately (and without a word being spoken) plugged in an emergency line which linked the office directly with the D/F stations. While the Simon's Town office was quite easily linked to the station at Smith's Farm, the connection in the case of the Overport Station was an incredible feat, as all the Post Office exchange operators linking the Simon's Town office to the D/F station would immediately disconnect any conversations on the special line and, within seconds, the call would be connected.

As described earlier, once the bearings had been obtained from the D/F stations, these were laid out on specially prepared charts, one for each station. The intersection of the drawn lines indicated the approximate position of the U-boat and this information was then passed on to the War Room, or Plot, and, simultaneously, a radio signal was sent to the Admiralty in London. Only very seldom was the signal sent to London before the U-boat had completed its transmission.

The charts at Simon's Town were not of the conventional Mercator's projection. Instead, great circle paths were drawn for each station, showing each degree of bearing. A tracing was placed over each chart, and the bearing received from the D/F station was added to this and the approximate location of the U-boat was identified. Great care had to be taken to ensure that a reciprocal bearing had not been received (for example, a reading from the Atlantic instead of the Indian Ocean), which sometimes occurred. Eventually, as more telegraphists became available for service in the special unit, space became limited. At the same time, the Commander-in-Chief's departments expanded and, eventually, the unit in Simon's Town was moved to Orange Street in Cape Town, where it was accommodated opposite the Labia Theatre.

Organization

The author was attached to a department in the Admiralty which was known as the Naval Intelligence Division. The section coutmiung the high frequency direction finding unit was known as the 'Y' Division and was primarily concerned with the interception of all enemy naval radio transmissions. The officer commanding the 'Y' Division, attached to the Staff of the Admiralty, was known as a Staff Officer (Y), or SO(Y), and while similar to the Staff Officer Intelligence, or SO(I), he headed an entirely separate department. In the case of the South African unit, Lt Bennett was SO(Y) on the staff of the Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic.

In the successful prosecution of the war, knowledge of enemy communication became essential. Thus, what had begun as a naval operation soon broadened to include the interception of all radio transmissions between Germany, Italy and Japan, mostly high speed Morse transmissions on high frequencies. The recording of this radio traffic required a greater number of highly specialized operators and equipment and also formed a part of the 'Y' service. Radio traffic between enemy countries was always in code and the rate of transmission was anything up to 60 to 80 or more words a minute - too fast for one operator to listen to and write down at once. Thus, recording equipment called an undulator, which was very similar to that used by the South African Post Office, was used. This machine, fitted with a pen which was controlled by the radio signal it received, 'wrote' on a moving paper tape. The pen moved up and down up when the Morse symbol (a dot or a dash) reached it and down when the signal ended. The speed of the tape running underneath the pen could be adjusted by the operator. It was possible to differentiate between a Morse dot and clash, because a dot moved the pen up for a brief second, while a dash moved the pen up for about three seconds. This action produced the dots and dashes (usually in a relationship of three to one) and, from this it was possible to read the coded message as a series of letters and figures. This was best done by one operator reading and calling out and another writing it down.

In Freetown, Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Central Africa, the Royal Navy constructed a radio station. The author believes that a South African by the name of Doug Rex from Port Elizabeth was responsible for the installation - a remarkable achievement, considering the type of labour and the dreadful climate. During the time that the author worked there (as one of the complement of 100 British officers and men), the main task carried out by the station was the interception of high speed radio traffic. There was a D/F station in the vicinity and another on Ascension Island, which the author visited by air from Lagos. The station was manned by employees of The Cable and Wireless Company, who also operated the cable links The author was appointed there as the officer in charge of the Aberdeen W/T Station. The information collected by this station (and another at Durbanville, near Cape Town, where the author was appointed later and worked in the company of Women's Royal Naval Service [WRNS] from England) was fed to the Admiralty in London and then to Bletchley Park for analysis.

The most incredible radio station imaginable, in the view of the author, was one situated at Cheltenham in England. The station consisted of acres of receivers, masts and aerials and served as the backbone of the entire network of interception stations and as the main source of intelligence required in the war.

Direction finding equipment

Amongst the equipment sent to South Africa by the Admiralty was a device known as a '249' or 'Two-Four-Nine', which was designed to measure the height of the ionosphere which played such an important role in the transmission of high frequency waves. The author is not aware of how it was to be used, where it was installed, or who used it, but believes that the Department of Physics at Rhodes University in Grahamstown has a machine capable of measuring the height of the ionosphere. The Admiralty also sent out an RFP (Radio Finger Printing) machine, which, it was believed, could detect the differences between the signals produced by individual radio transmitters.

The 'undulator' mentioned above was a machine which was designed to record and 'write' down Morse Code signals transmitted at high speed on a moving paper tape. The pen of this machine was fitted to an arm which was activated by the Morse signal and the speed of the moving paper tape could be adjusted to suit the speed of the transmission. The dots and dashes recorded on the paper could later be 'read' by an experienced operator and written down by hand.

Conclusion

Any experienced radio operator was capable of reading a Morse signal transmitted in plain language at a rate of 60 words or more a minute. As a radio ham, the author was thus capable of reading the daily news transmitted by Morse Code in English by the British 'Rugby Radio'. Sadly, however, the individual art of sending and receiving Morse Code over the air has almost died completely and of the amateur radio operators who still use it to day, some are now using computers to do the sending and receiving.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org