The South African

The South African

by Major J D Harris, sometime of the Queen's Dragoon Guards

Line communication

Before 1899, a permanent line had been established along the Delagoa Bay railway line (as along all railways in South Africa), while another ran north-west along the railway from Nelspruit to Pilgrim's Rest to Kruger's Post and on to Lydenburg and then northwards. The various mines in the Sabie-Pilgrim 's Rest area were connected to this system and, as it remained in Boer hands for virtually the entire war, it afforded General Ben Viljoen a useful communications system for his commandos there.(1) Not much further afield, The Times History of the War in South Africa asserts that even after the capture of Pretoria by the British in June 1900, the Transvaal Government at both Pietersburg and Roos Senekal maintained line communication with the commandos under Botha and De la Rey(2), but this could hardly have been continuous.

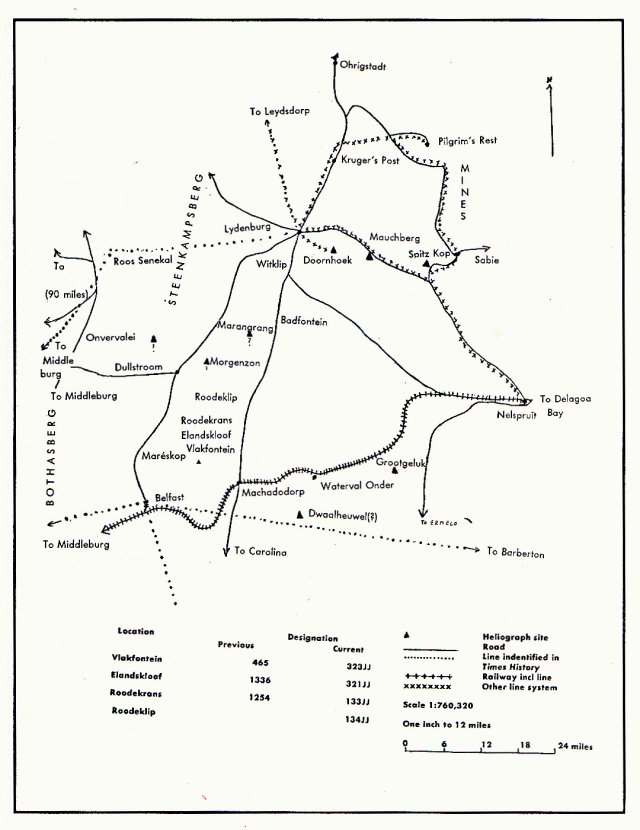

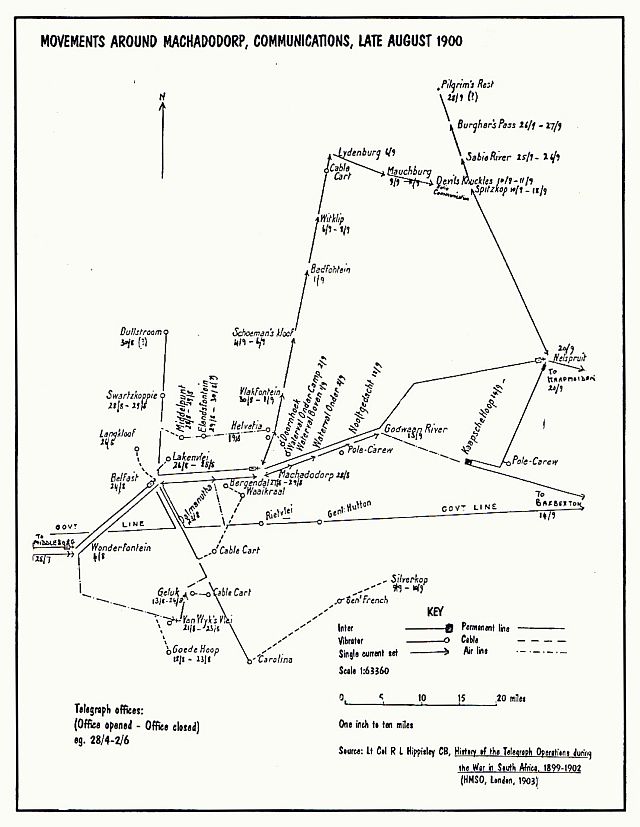

The British Army expanded their system to include their fortified positions and blockhouses (see map I). Tactical extensions of the network were provided by divisional cable carts(3), by whose movements the daily locations of divisional, brigade and often column headquarters could be traced.(4) (Map II shows a typical example in our area of interest).

Map I: Laid line and some heliograph sites

in the Eastern Transvaal, 1901

Map II: Movements around Machadodorp -

Communications, late August 1900

The two chief drawbacks of line from the military point of view were that the line itself was readily cut and that messages could be intercepted by tapping. On occasion, the line itself was used by the opposition to pass its own traffic. Line cutting was an occupation much favoured by the Boers, as not only did it interrupt British communications, but it also provided splendid opportunities for ambushing British lines parties with inadequate escorts. For instance, on 3 May 1901, the Manchester Regiment's line parties suffered casualties. 'The telegraph wire between Witklip [Just south of Lydenburg] and Badfontein, having been cut during the previous night, parties were sent out from each end but were attacked by about 50 Boers. The fire was so heavy that it was impossible to mend the wire, which was found to be cut in twelve places. One native killed, L/C Davies, 1st Manchester, slightly wounded, two men missing.'(5) Similarly, line tapping was a most popular Boer activity. To overcome it, the British fed false information down their line in clear and later encoded messages and corrections gave the intended communication. Latin was considered secure, but with General Smuts having little else in his saddlebags but Kant's Critique of Pure Reason and a Greek New Testament(6), while General Hertzog had his Tacitus with him, clearly Latin was less secure than the British believed. Satis dicit.

Communication by heliograph

The heliograph provided the mobile element in the British service and was even more important to the Boers, who controlled so much less line. The word 'heliograph' is derived from the Greek helios (sun) and graphos (writing). In heliography, a mirror is used to flash light in Morse code. Using this method, eight to sixteen words could be transmitted per minute and the equipment was relatively cheap and easy to manufacture - in the absence of anything else, a simple mirror would suffice - and a 'crew' of only one trained person was required. Marching distances (ranges) varied roughly, depending on the size of the reflector. For example, a 5 inch (12,7 cm) reflector had a marching distance of some 50 miles (80,5 km), whilst the 9 or 12 inch (22,9 or 30,5 cm respectively) models had a range of up to 80 miles (128,7 km). Indeed, in India, marching distances of over 100 miles (161 km) had been recorded and it is interesting to note that, at least until 1975, the Pakistan Army continued to use the heliograph.

The main disadvantages of the heliograph were that a light source was required, be it the sun, the moon, or limelight, and that a clear atmosphere was essential. Tactically, interception was possible anywhere along the axis of the projected light beam, but this was sometimes much reduced in diameter by the use of a narrow tube. Even a rifle barrel could be used to project the beam. The disadvantage in this was that the marching distances of very narrow beams were also less, as less light was radiated.(7) (For a list of the various characteristics of line and heliographic communication, see Table I).

| EQUIPMENT | MARCHING DISTANCE (RANGE) | SPEED (WORDS PER MINUTE) | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electric telegraph | Limited only by length of line | 300 | 24 hours service |

| Telephone | Limited only by length of line | 200 | 24 hours service |

| Helio 12" reflector | 83.5 miles (134 km) | 8-16 | Sunlight |

| Helio 10" reflector | 83.5 miles (134 km)a | 8-16 | Sunlight |

| Helio 9" reflector | 83.5 miles (134 km) | 8-16 | Sunlight |

| Helio 5" reflector | 52.5 miles (84.5 km) | 8-16 | Sunlight |

| Helio (saddle) 3" reflector | 37 miles (59.5 km) | 8-16 | Sunlight |

| Helio (limelight) 5" reflector | 31 miles (50 km) | 8-16 | |

| Helio (moonlight) 5" reflector | 12 miles (19.3 km) | 8-16 | Strong moonlight |

| Lamp, trench pattern shutter | Short and variable | 4 | |

| Lamp, electric, daylight signalling | Not stated, estimated 30 miles (48.2 km) | 8-16 | |

| Flags, Largeb | Difficult over 5 miles (8 km) | 2c | Faster with silk flags and Morse code, slower using semaphore |

Notes:

a. Using the 10-inch reflector in ideal conditions, marching distance of over miles (160km) were recorded in both India and China.

b. Pigeons were also used, as were searchlights in conjunction with shutters, as Admiral Sir Percy Scott records in his autobiography (8)

c. Highly skilled operators were capable of six words per minute.

Source: Alan Harfield, Early signalling Equipment: The Heliograph a Short History (The Royal Signals Museum, 1986).

In the British Army, heliographs were issued to at least regimental/battalion level and, of course, each column had its own equipment. In the Eastern Transvaal, there is evidence to indicate that the heliograph was used as a back-up for the permanent line along the railway and blockhouse lines. Another feature was that a column on an operation could plug into the nearest railway/blockhouse system, and the message could then be sent on by line or heliograph.

To the Boers, the heliograph must have been absolutely essential. How else could General Louis Botha have monitored Colonel Benson's movements, coordinated the movements of the Bethal, Middelburg and Pretoria commandos, and then arrived himself with 500 men from the Ermelo and Carolina commandos after a march of 70 miles (112,63 km) to ensure disaster to Benson's Column, the death of the latter and so many of his officers and men at Bakenlaagte on 30 October 1901? Further, as the British blockhouse lines became more and more difficult to cross, the heliograph became the most practical and the fastest way of getting information, intelligence and orders across them. A system of sites for heliographs must have been built up to accommodate this traffic and this is where some speculation is necessary in our area of interest.

The cardinal point in any heliograph network passing messages from the north to 'somewhere south of the Delagoa Bay railway' between Belfast and Machadodorp must have been Mareskop - its height, extended views (especially north and south), the difficulty of unobserved approach, and the easy withdrawal route via Elandskloof to Boer positions at Roodekrans and the north made it ideal for this purpose. Evidence of the occupation of Mareskop lies not only in its breastworks, but also in reports from British sources over a six month period (see Table II). Having established the cardinal point, it is easy to construct a network, albeit with speculation in places. Further, it can be readily integrated into the line system, thereby giving it excellent local coverage (see Table III).

| DATE | REPORT ON VLAKFONTEIN | COMMENT | SOURCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| w/e 15 December 1901 | Schalk Buger's pickets | Intelligence Reports | |

| 25/26 December | Schalk Buger engages Col Park | Burger reported to have 150 men with HQ at Roodeklip | Intelligence Reports Marden |

| w/e 5, 12, 19 January 1902 | Locations static | Intelligence Reports | |

| w/e 2 Feb | Boer heliograph station confirmed by British near Elandskloof | Intelligence Reports | |

| w/e 16 Feb | AFC Bass at Roodeklip with 40 men | Intelligence Reports | |

| w/e 23 Feb | Schalk Burger reported to be on way to join De la Rey | Intelligence Reports | |

| w/e 2 March | Lucas Grobler establishes post at Elandskloof from his HQ at Witbooi | Schalk Burger gives up attempt to join De la Rey | Intelligence Reports |

| w/e 9 March | AFC Bass evacuates Elandskloof | Probably occasioned by the return of Schalk Burger | Intelligence Reports |

| w/e 16 March | Part of S Trichardt's commando at Roodekrans and Roodeklip | Intelligence Reports | |

| w/e 30 March | Part of Gen Muller's commando at Roodeklip | Intelligence Reports | |

| 31 March | Col Urmston considers raid on Vlakfontein but does not carry it out | Subsequently Urmston reports no one was there. Reality may have been different. | Staff diary |

| w/e 6 April | FC Bass with 70 men at Elandskloof | P Taute with 40 men at Roodekrans, and 30 men at Roodeklip | Intelligence Reports |

| w/e 4 May | FC Taute keeps post of 20 men at Elandskloof | Taute's HQ his farm Suikerboschkop | Intelligence Reports |

Sources:

Intelligance reports: British intelligence reports, Public Records Office, Kew, WO 188/132, pp 397-625.

Marden: Marden and Newbigging, A rough diary of the doings of the 1st Battn Manchester Regiment, 25 December 1901.

Staff Diary: Col Urmston's Column Staff Diary, PRO Kew, WO 32/8101, Part 1, 31 March 1902.

Importantly, one can note the ease with which messages could be beamed from Mareskop to a position south of the railway (such as Dwaalheuwel), or north to Viljoen's commandos in the Mauchberg or perhaps Doornhoek, or to the government in the Steenkampsberg or at Roos Senekal via Ondervalei or a site nearby, or of course very locally to General Muller or Acting President Schalk Burger in the Roodekrans and Roodeklip areas and other neighbouring farms. The necessary speculation as to the precise position of each site should not detract from the general thesis, for the heliograph was so mobile a system that a large selection of sites from which long marching distances could be achieved, was available. Thus, a heliograph and line system with considerable flexibility and even redundancy had materialized, allowing the Transvaal Government and its forces relatively good communications in this part of the eastern Transvaal which, although in African terms is a small area, must reflect light on Boer communications elsewhere in the Orange Free State and the Transvaal itself.

| LOCATION SOURCE HEIGHT (in metres) |

Kruger's Post Hippisley 1 299 m | Lydenburg Hippisley 1 451 m |

Nelspruit Hippisley 300 m | Pilgrim's Rest Hippisley, Viljoen 1 240 m |

Sabie Hippisley, Viljoen 1 204 m | Spitzkop Hippisley, Viljoen 1 675 m |

Doornhoek Viljoen 1 961 m | Mauchberg Hippisley 2 209 m |

Morgenzon Speculative 2 162 m | Onvervalei Speculative 2 274 m |

Marangrang Speculative 2 040 m | Bothasberg Speculative 2 000 m |

Dwaalheuwel Speculative 1 984 m | Maréskop British Intelligence 2 018 m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kruger's Post* | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | |||||||

| Lydenburg * | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | |||||||

| Nelspruit * | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | |||||||

| Pilgrim's Rest | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | |||||||

| Sabie | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | |||||||

| Spitzkop | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line, Helio 11 miles (17,7 km) | Helio 46 miles (74 km) | ||||||

| Doornhoek | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line, Helio 5 miles (8 km) | Helio 28 miles (45 km) | Helio 28 miles (45 km) | Helio 18 miles (45 km) | Difficult Helio 40 miles (64 km) | Difficult Helio 36 miles (58 km) | ||

| Mauchberg | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line | Line, Helio 11 miles (17.7 km) | Line, Helio 5 miles (8 km) | Helio 42 miles (67,5 km) | Helio 35 miles (56 km) | Difficult Helio 23 miles (37 km) | Helio 40 miles (64 km) | |||

| Morgenzon | Helio 42 miles (67,5 km) | Helio7 miles (11,2 km) | Helio 8 miles (12,8 km) | Helio 23 miles (37 km) | Helio 14 miles (22,5 km) | |||||||||

| Onvervalei | Helio 35 miles (56 km) | Helio7 miles (11,2 km) | Helio 13 miles (21 km) | Difficult | Helio 20 miles (32 km) | |||||||||

| Marangrang | Difficult Helio 23 miles (37 km) | Helio 8 miles (12,8 km) | Helio 13 miles (21 km) | Helio 24 miles (38,6 km) | Helio 16 miles (25,7 km) | |||||||||

| Bothasberg | ||||||||||||||

| Dwaalheuwel | Helio 23 miles (37 km) | Helio 31 miles (50 km) | Helio 14 miles (22,5 km) | |||||||||||

| Maréskop | Helio 40 miles (64 km) | Helio 14 miles (22,5 km) | Difficult Helio 20 miles (32 km) | Helio 14 miles (22,5 km) |

To conclude, the story of line communication in the South African War is well documented, but the chase for chronicles of the heliograph is by no means over. Indeed, perhaps some readers might like to join the author in his hunt and to complete the story of the heliograph?

Me that 'ave watch 'arf a world

'Eave up all shiny with dew,

Kopje on kop to the sun,

An' as soon as the mist let 'em through

Our 'elios winkin' like fun -

Three sides of a ninety mile square,

Over valleys as big as a shire -

'Are ye there? Are ye there? Are ye there?

An' then the blind drum of our fire...

Kipling, Chant-Pagan

References

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org