The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

In 1980, the author began his spare-time field study and research into the blockhouses and other fortifications erected by the British forces in South Africa during the South African War (1899-1902). There being very little information available on the subject at that time, the process has been an ongoing and absorbing passion ever since and there is still much to be learned. However, with the centenary of the war only a couple of years away, he considers that the time has come to record some of his findings and conclusions, to stimulate the interest of all who are involved in the recording and preservation of these structures and to inform others who enjoy military history and old buildings. The author emphasises from the outset that the following observations are of an interim nature and may be amended as further information comes to light and more field studies are undertaken, but he believes that this is a starting point.(1)

Definition of a masonry blockhouse

Brevet-Colonel EH Bethell, the Royal Engineers officer who wrote a

well-known paper after the war on the blockhouse system, did not know what

the word 'blockhouse' signified.(2) The term appears to have been used

first to describe the smaller coastal batteries built during King Henry

VIII's defence of the English coasts in the 1530s and 1540s, as distinct

from the larger structures which were termed 'castles'. The term is encountered

again in South Africa in the early nineteenth century when it was used

to describe three masonry towers built by the British on the slopes of

Table Mountain to protect Cape Town and two prefabricated wooden towers

which were shipped to Algoa Bay to safeguard a landing place of what later

became known as Port Elizabeth. For the purposes of this article, a 'masonry

blockhouse' is defined as a structure of mortared stonework or concrete,

one to three storeys in height, with a roof of timber and corrugated iron

or concrete, with rifle ports, windows and doors protected by loopholed

steel plates and with or without steel machicouli galleries.

The drystone bases of corrugated iron blockhouses and the irregularly shaped drystone forts constructed by infantry regiments, although an interesting study in themselves, do not fall within the scope of this article. Similarly, the small mortared masonry fort sunk into a hilltop in Monument Extension 1, Krugersdorp [G] (and excavated by the South African Archaeological Society in 1987)(3) and the three unmortared square towers in the fort to the south-west of Heidelberg [G] have been omitted from this study.

Number of masonry blockhouses built

A summary of the returns from the Commanding Royal Engineers (CREs)

of the districts throughout the country and dated 12 May 1902,(4) gives

a total of 441 masonry blockhouses, as distinct from corrugated iron blockhouses

and 'works'. As it is most unlikely that any further masonry blockhouses

would have been constructed between 12 May and the end of the war on 31

May 1902, this figure can be regarded as final.

It should be noted that there are some discrepancies in the numbers of masonry blockhouses recorded in individual CRE's reports when compared with this summary. For example, Major WH Turton (CRE Western District [Transvaal]) lists nine masonry blockhouses in the area as at 20 May 1902,(5) but the summary records eleven. In the Orange River Colony (Free State), the CRE gives a return of 51 as at 11 June 1902,(5) against the summary's 58. However, as a large number of the masonry blockhouses have been demolished, and some of the sites have even been lost through the widening of road and railway cuttings and in the course of urban and industrial development, we shall probably never be able to confirm the exact number of blockhouses built.

Dates of construction

The earliest masonry blockhouses appear to have been constructed during

the early months of the guerrilla phase of the war, ie, after the fall

of Pretoria on 5 June 1900. The CRE, Pretoria District, records that Johnston's

Redoubt, East Fort, and Howitzer Redoubt [G] were 'well advanced' by 1

December 1900.(6) From the CREs' reports which provide dates, it seems

that most of the masonry blockhouses were built between 1 December 1900

and 31 December 1901 (described as Period B).

The only other evidence of dating, noted by the author, was found at the actual blockhouse sites. For example, at Hekpoort (Barton's Folly) [G], the figures '9-1901'can be seen cut into the wet mortar of the parapet wall and, at Warrenton [NC], the date 'MDCCCCII' (1902) and the initials of the Royal Engineers company and individual soldiers involved were incised into the plasterwork of the window sill of the blockhouse by the railway bridge. In both cases, the inscriptions appear to be original.

Location of the blockhouses

Contemporary Royal Engineer sources(8) state that masonry blockhouses

of a design by Major-General E Wood (Chief Engineer), were erected at important

points such as railway bridges over rivers. However, they were also to

be found guarding railway stations (such as the one at Warmbaths [NP]),

railway lines in open country (such as those at Witkop [G] and other points

on the Vereeniging line), towns (including Harrismith [FS], Aliwal North

[EC], and Pretoria [GJ] and passes and high points in the Magaliesberg

(such as the four examples which defended Kommandonek [NW] and the well-known

Hekpoort blockhouse mentioned above). The use of masonry blockhouses at

railway bridges is consistent, but in the other locations cited, there

seems to have been no firm rule and masonry and corrugated iron structures

were interchangeable. The reason for this may be that many of the masonry

examples were built at the end of 1900 and in the early months of 1901,

before the mass-production of corrugated blockhouses began. Major Rice

introduced an octagonal corrugated design in February 1901 and only invented

his circular corrugated blockhouse later. By this time the Boers had lost

most of their artillery and the double-skin corrugated iron wall with the

shingle filling provided sufficient protection against rifle fire. The

high cost and long construction period of the masonry blockhouses also

probably swayed opinion in favour of the corrugated design. In spite of

this, the advantage of the additional height of the three-storeyed masonry

structure may have allowed further examples of this type of blockhouse

to be built at a later date in flatter terrain.

Design variations

To the average tourist who has seen masonry blockhouses along the Cape

Town-Johannesburg railway line, these structures may appear to be identical,

although in variable states of repair. To the author, however, it is the

wide variety of blockhouse designs, many of which formed distinct regional

groups (described below), that aroused his interest:

The standard pattern

This type of blockhouse is based on Major-General Wood's standard design

and is found extensively along the Cape Town-Warrenton railway line; on

the East London-Aliwal North railway line at the Stormberg Junction [EC]

and Burgersdorp [EC]; and defending the towns of Aliwal North [EC] and

Harrismith [FS]. Along the railway lines, these standard pattern blockhouses

defended major river bridges, while corrugated ones were found at intervals

to cover the railway line itself.

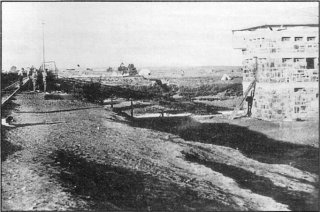

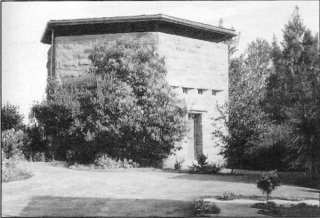

A view of the standard pattern Modder River Blockhouse,

taken during the war. (Photo: McGregor Museum).

The standard pattern blockhouses were constructed of mortared stonework or reinforced concrete and measured 6,1 m square externally. They were almost always three storeys high, the ground floor typically being used as a storage area, the first floor as a living area and the second floor for observation over the countryside under a pyramid-shaped timber and corrugated iron roof, with small gabled extensions over the steel machicouli galleries. The latter were cantilevered out from the walls at two diagonally opposite corners to allow flanking fire along the wall faces in the case of an attack.

The ground floor had two loopholes per wall. The entrance door was situated on the first floor, which also had three windows (one in the centre of each wall) and there were two loopholes on either side of these openings. The second floor had four loopholes at low level in each of the parapet walls, the gap between the top of the parapet and the eaves of the roof being closed by canvas 'drops', which could be rolled up in fine weather. The walls of the blockhouse were 900 mm thick on the ground floor, 600 mm on the first floor and 450 mm on the second floor, the internal offsets carrying the upper timber floors.

Access to the blockhouse was by a ladder to the first floor, which could be drawn up inside in the event of an attack. Similar ladders inside the building gave access to the floors above and below. The roof was fitted with galvanised gutters which discharged rainwater through internal downpipes to circular corrugated iron water tanks on the ground floor, in the two corners opposite those occupied by the machicouli galleries. The tanks were topped up regularly in dry weather, by train (in the case of railway blockhouses) or by water carts brought in from adjacent garrison towns. Food, ammunition, mail, etc, was delivered in a similar manner. The stable-type door, window shutters, loophole plates and galleries were all made of 10-13 mm thick steel plate,(9) each with a 100 x 75 mm, or a 100 mm circular, loophole through which to fire.

The author has found only one exception to the three-storey rule in the standard pattern blockhouse. This is the two-storeyed Orange River Station Blockhouse [NC], situated south of the river on the De Aar-Kimberley line. This blockhouse is built on a thick concrete foundation, reinforced by two rows of railway lines (to stabilise the structure on the sand dunes) and the entrance is on the lower floor level. The construction was not totally successful, as the two loopholes nearest to the south corner on the lower level have been blocked, internally, by stonework.

Orange River Station,

a two-storeyed standard pattern blockhouse.

There are a few minor variations in the design of standard pattern blockhouses around the country. Around Harrismith, these structures exhibit a gabled instead of a pyramidal roof, with vertical corrugated cladding on the gable ends and the roof is cut back over the machicouli galleries. There is only one loophole on each side of the entrance at first floor level.(10) The small monopitch roofs and vertical cladding covering the galleries on the Reservoir Blockhouse at Harrismith represent another original variant to the design.(11)

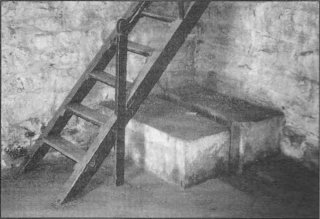

The Reservoir Blockhouse, Harrismith.

The group of standard pattern blockhouses at Stormberg Junction, Burgersdorp and Aliwal North (Buffelspruit) in the Eastern Cape have square rather than the customary circular bases for the ground floor water tanks, with a drainage slot cut through each base to the overflow opening through the external wall. Some examples (including those at the Stormberg Junction and Buffelspruit) have had a doorway inserted at ground floor level at a later date when the blockhouses were 'recycled'. This enables visitors today to view the interior of the blockhouse more easily, without having to carry a ladder. In addition, the Stormberg Junction South Blockhouse has staircases to both of the upper levels, which, judging by the spacing of the floor joists, appear to be an original feature. That there would not have been space for a water tank beneath the lower staircase may be accounted for by the easy availability of water at the nearby railway station.

The Stormberg Junction South Blockhouse.

Note the square water tank base.

The standard pattern at the Vaal River railway bridge at Warrenton [NC] is yet another variant. There are no machicouli galleries here, but there are chamfered corners above the level of the loophole sills on the first floor. This building also has only one shuttered window on this level, opposite the entrance. There is one loophole on each side of the door and window, the other two walls being pierced by three loopholes per side and an angled loophole inserted at each corner (see the Magaliesberg pattern below, where the chamfered corners and angled loopholes are a regular feature).

The Warrenton Railway Bridge Blockhouse.

These masonry blockhouses were generally erected by contractors under the supervision of Royal Engineers personnel. Three contractors were employed to build the eighteen blockhouses between Wellington [WC] and Richmond Road [NC] along the Cape Town-De Aar railway line in the early part of 1901. The contract time allowed was six weeks, but delays in railway transport, the incorrect delivery of material, shortage of labour, etc, resulted in greatly extended building periods. The western blockhouse at the Breede River [WCJ took five months and eleven days to complete,(12) indicating that 'don't you know there's a war on' had little effect even during Victoria's reign!

Mortared stonework blockhouses were considered preferable to the concrete ones as less cement was used (90 casks for stonework and 160 for concrete), a harder face and neater appearance were achieved, and the quality of the work could be more easily checked. Of the fourteen out of eighteen blockhouses between Wellington and Richmond Road (Merriman) which the author has been able to inspect, five (one at Merriman [NC], two at Krom River [WC], one at Laingsburg [WCJ and one at De Wet [WC]) were built of concrete and two of these (Krom River North and De Wet), which were located near to a river, have collapsed. The concrete blockhouses were possibly constructed in areas which had no natural stone, or they may have been experimental. Stone for masonry blockhouses was generally quarried on site, but could also have been transported by train for those blockhouses situated near to a railway line. Other patterns of masonry blockhouse examined were all built of mortared stonework.

A concrete standard pattern at Merriman.

The report of Colonel Morris, CRE, Cape Colony, makes various recommendations for the construction of masonry blockhouses. This makes for interesting reading, particularly for their value in hindsight, as many of the suggestions are seen not to have been used in the well-preserved examples (12) The major points in the report are summarised below:

'On alluvial sites it is better that the footings and floor should be cast together...' This is difficult to verify without excavation.

'Instead of wooden banquettes for ground floor loop-holes, it is simpler to "build in" a masonry banquette...' The author has never seen this in a standard pattern blockhouse.

'Water tanks should be inside the building and not buried outside. They are safer and more convenient and can be more easily washed out.' This practice was generally adopted. However, at Mooi River [NC], a buried external tank is visible in contemporary photographs.

'The doors and shutters should be fitted with steel and not teak jambs, the steel jambs should be of angle or channel section and set through the sills with the hinge pins and hasps rivetted to them...' This was not always followed, which could result in bullets passing through the wooden jambs.

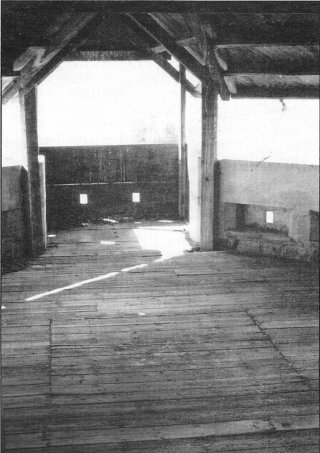

'Trap doors should be in diagonal corners, and not in the centre of the floor (2 ft 6 inches [760 mm] square is an ample size). Placed thus, the danger of falling through them is practically obviated and standards and chains for their protection rendered unnecessary.' This is a classic example of hindsight as the surviving timber upper floors seen by the author invariably had traps in the centre of the floor and they were 1 500 mm square; on the second floor, the trap is set between the steel rails which run diagonally through the building and support the two machicouli galleries, thus dictating the trap size; and on the first floor, the trap is set square to the floor plan but is still the same size. At Stormberg Junction South, despite the timber staircases at both levels, there are still the mandatory central traps in both floors, which seems to suggest that they were necessary for moving stores or weapons down to the ground floor or up to the second.

Interior of the top floor at Stormberg Junction South,

showing the trap door and machicouli gallery.

'The inside ladders should be of iron and fixed vertically. Wooden ladders are cumbersome, get broken and are apt to be used as fuel' - a practical suggestion regarding the material to be used, but vertical ladders between the floors would make hasty climbing more difficult, especially if the soldier was carrying something. General Wood had sloping ladders in his design.

'Angle galleries should be built into the walls and not have the vertical plates butted against them...' This generally was not done and gaps have appeared between the steel and the masonry. However, the passage of time and neglect may account for some of these gaps.

'The floor loopholes should be placed outside supporting railway irons, otherwise the latter tend to mask the fire.' This suggestion was not always followed, but the four circular holes gave fair coverage of the wall faces.

'The air space below the eaves of the roof should not be too large and should be masked by a canvas drop to keep out driving rain.' This seems to have been a standard practice.

'Interior walls and woodwork should be limewhited, this increases the light, preserves the timber and makes for cleanliness.' This seems to have been adopted generally and traces of limewash can still be seen today inside many of the blockhouses. At Merriman and Brakpoort [NC] in the Karoo, the dry climate has preserved the limewash in its entirety and, interestingly, the whitened loophole plates are numbered in black paint, presumably to facilitate speedy dispersal of each soldier to his post in the event of an attack.

'A protecting, sliding or swinging flap for loopholes is desirable, both as a protection against draughts and to prevent unused loopholes [from) being fired into by the enemy during an attack.' The author has never seen this device in a blockhouse. Denys Reitz, in his book, Commando, records that he fired into the loopholes of a fort during the Smuts Commando's attack on Springbok [WC] in April 1902, resulting in the deaths of several of the defenders and the perforation of the water tank which led to the capitulation of the garrison.(13) The garrison for a standard pattern blockhouse appears to have varied according to the availability of men and the degree of danger in the area at the given time. It ranged from seven to forty men, commanded by a subaltern or senior NCO.(14)

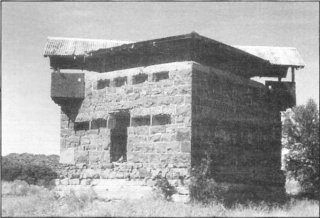

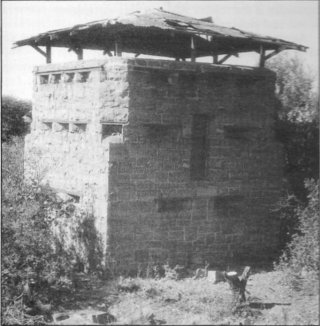

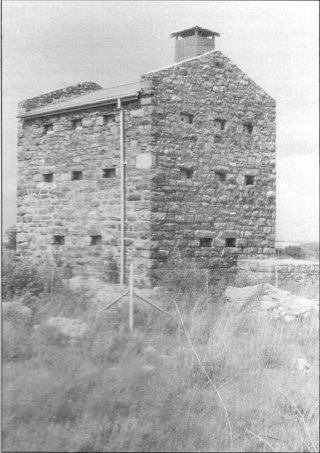

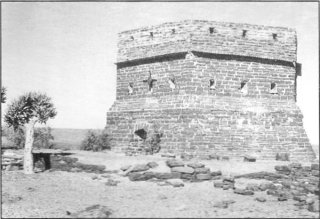

The Magaliesberg pattern

A most distinctive type of masonry blockhouse is found defending the

passes and high points of the Magaliesberg region to the west of Pretoria.

Clearly designed by an engineer with an affinity for medieval military

architecture, they feature crenellated parapets above a flat roof, a wide

range of plan shapes and the chamfering of external angles above the loophole

sills to accommodate additional loopholes at the angles.

The different plan shapes show an almost perverse variety. The group of three on the mountain to the east of Kommandonek [NW] are, respectively from the bottom, square, T-shaped, and L-shaped. The blockhouse to the west of the nek is rectangular. The example at Hekpoort has a chevron or obtuse arrowhead shaped plan. All the Magaliesberg pattern blockhouses are single-storeyed and, where they are constructed on a rounded hilltop, the site has been levelled with a terrace comprising a surrounding revetment of unmortared stonework and a flat bed of small stone chippings.

The flat roof of the Hekpoort blockhouse comprises steel I-beams supporting arched sections of corrugated iron,(15) on which concrete has been poured to form a deck with a slope to direct rainwater to two outlet holes through the parapet walls on the inside faces of the chevron shape. The Kommandonek East lower and middle blockhouses and the Kommandonek West one were roofed in a similar manner, as witnessed by the fallen concrete rubble with impressions of corrugated iron upon them. The upper example at Kommandonek East and that at Broederstroom [NW] had flat roofs of lighter construction, probably timber and corrugated iron.

The Magalieberg pattern blockhouse at Hekpoort.

These blockhouses each had the standard steel stable door, shuttered windows and loopholes; the windows in the short end walls at Hekpoort were positioned above the loopholes and were so high above the floor level that an iron strap step was built into the wall below the loophole to give access to the window. The floors were of boarded and joisted timber, carried on wall offsets, with extra sleeper walls in some instances and with openings for ventilation of the space beneath the floor.

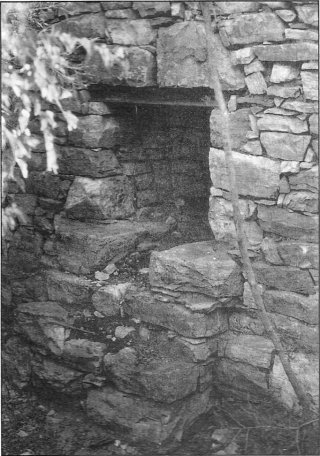

One unique feature of the blockhouse at Broederstroom is the fireplace in the middle of one of the long walls. It had offsets to support a grate, a bar to hang a kettle or cooking pot on a hook above the flames and the wall is thickened externally to accommodate the flue. When one considers the cold winters experienced in many parts of South Africa, it is surprising that this was not a regular feature in the masonry blockhouses.

The fireplace at the Broederstroom blockhouse.

Another feature associated with the Magaliesberg pattern blockhouses, resulting from the mountainous terrain in which they are located, is the existence of mule tracks leading up to them from nearby roads. These tracks are generally 1,5-2 m wide, revetted in drystone on the lower side (occasionally on both sides) to a height of anything up to two metres and finished on the top with a bed of fine stone chippings. They are usually in a good state of repair, despite being used today as hiking trails. One of the best, although built for a corrugated blockhouse, runs up the ridge of the Magaliesberg to the west of Pampoennek for a total distance of about half a kilometre.

A well-preserved mule track at Pampoennek.

There were several Magaliesberg pattern blockhouses within the present municipal area of Pretoria which have been demolished but which were photographed before they disappeared. The best known of these was situated at Wonderboompoort.

The Daspoortrant pattern

This type is peculiar to the mountain ridges around Pretoria and is

characterised by a regular rectangular plan (measuring 6,1-6,25 m wide

and 11-11,3 m long outside) with wall offsets and a central sleeper wall

running along the length of the interior to carry the timber floor. Most

examples found have been destroyed above the level of the floor offset

so that other features of the design are uncertain, but old photographs

of what appear to be Daspoortrant pattern blockhouses show a preference

for gabled corrugated or flat roofs, steel angle galleries and single-storeyed

construction. The galleries on these examples are square in plan with the

outer corner cut off, unlike the rectangular galleries of the standard

pattern.

A variant of the Daspoortrant pattern is represented by the only complete stone blockhouse in Greater Pretoria, Johnston's Redoubt, situated in the grounds of Libertas, Bryntirion. This structure is 6,2 m square externally, single-storeyed with galleries, and it has a door in the centre of the side facing south, which is flanked by a loophole on either side. The remaining three walls each have a shuttered window and three loopholes. The foundations of a similar blockhouse are visible on Daspoortrant East, the ridge to the north of the Rietondale Experimental Farm.

An intricate system of stone-edged sentry paths and tracks linking the blockhouses at Daspoortrant was found extending out towards Kruger's West Fort, incorporating some additional drystone skantzes. The stones edging the paths would have been limewashed to make the paths more visible.

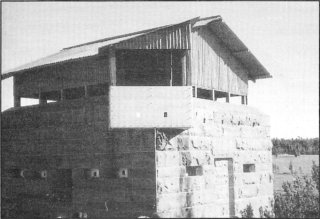

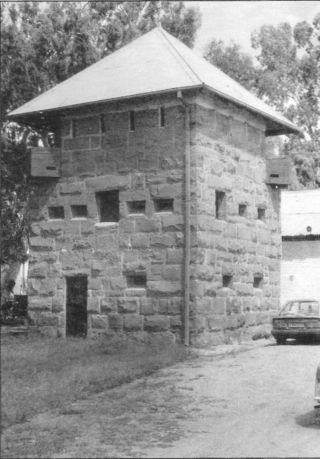

Vereeniging pattern

A very distinctive design is found along the railway line from Vereeniging

to Elandsfontein (present-day Germiston), now represented solely by the

preserved example at Witkop [G]. These came in two and three-storeyed versions

(Witkop being three-storeyed) and were covered with a corrugated gabled

roof with the gable and walls rising above the roof. A small turret of

timber and corrugated iron is positioned near one end of the ridge of the

roof and, approached by a ladder from inside, would have provided a clear

view over the surrounding countryside. A most unusual feature of this type

of blockhouse is the pair of angle bastions at diagonally opposite corners,

which were designed to provide for flanking fire along the walls, similar

to the function of the machicouli galleries on other patterns, but at ground

level. The bastions were flat-roofed, about one metre high an measured

2,5 x 0,9 m in size inside, so that each could only accommodate one man

and must have been very cramped and claustrophobic. The Witkop tower measure

6,15 x 6,75 m externally.

The Vereeniging pattern blockhouse at Witkop.

Note the angle bastion at the right-hand corner.

The design has wall offsets at the upper levels to support the timber floors, two loopholes in each wall on the ground floor, and two in each bastion and three in each wall on the upper storeys, the entrance taking the position of the central loophole in the east wall on the first floor at Witkop. There were no windows in this pattern so it must have been very dark and hot in summer.

The much photographed example by the railway bridge over the Vaal River at Vereeniging(16) has been demolished and a two-storeyed version, represented in photographs in MuseuMAfricA, Johannesburg, and probably located at Daleside,(17) is also assumed lost. The latter was more elongated in plan than Witkop, with the entrance positioned in a short end wall on its upper floor.

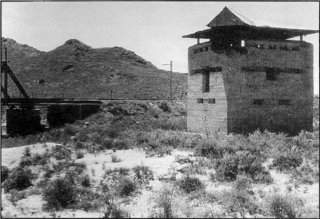

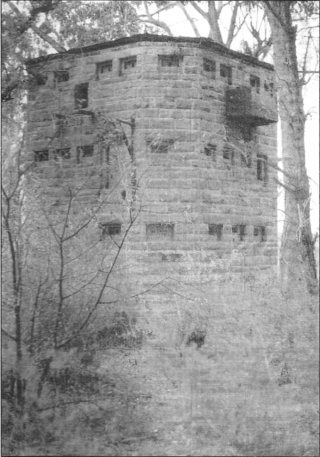

Orange River octagonal pattern

This type of blockhouse is represented by at least two well-preserved

examples, situated, respectively, to the south-east of the road and rail

bridges over the Orange River at Norvals Pont [NC] and to the east of the

railway line at Riversford [FS], 40 km south of Bloemfontein. The latter

is the better to view as the former has been converted into a dwelling,

is situated on private property and is largely obscured by creepers. The

author has established that a third example of this pattern was positioned

to the north-west of the Norvals Pont bridges, this and one other being

known from photographs held by MuseuMAfricA in Newtown, Johannesburg.

Three-storeyed, this pattern is in plan a square with the corners cut off, covered with a shallow-pitched corrugated roof which rises to a central ventilation turret.(18) The ground floor has three loopholes in each main wall and one in each splayed corner. The first floor has the entrance door and three shuttered windows respectively at one end of each main wall, with three loopholes in each of the main walls and one at each corner. The top floor has a shuttered window in the middle of each main wall, which opens onto a rectangular machicouli gallery, with two loopholes on either side of each window and, again, one in each corner. The entrance had, unusually, a steel landing outside, with the ladder running against the wall to ground level (blockhouses generally had a ladder at right angles to the wall). In both surviving examples, the door faced the railway and both still feature a steel gantry hoist fixed to the outside wall by the doorway, presumably to assist with the lifting of supplies into the blockhouse. Internally, the Riversford blockhouse has wall offsets to carry the upper floors, and the floors on both levels were unusual in that railway lines were used extensively in the timber floor construction, partly to support the cantilevered galleries on the top floor, although these are also present at the first floor level. From an architectural perspective, this is probably the most satisfying of the blockhouse designs.

The Orange River octagonal pattern blockhouse at Riversford,

with the gantry hoist to the right of the upper doorway.

Aliwal hexagonal pattern

Two examples of this pattern have survived in Aliwal North [EC]; one

in the suburb of Dewetsville being in good condition and a declared national

monument, and the other on a hill near the waterworks to the south-east

of the town centre, a roofless ruin.

Each blockhouse is two-storeyed, with the entrance in the middle of one side at ground level and with four loopholes in each wall. The curious feature of these loopholes is that they are three metres above the lower floor level so that, in the absence of any visual evidence, they must have been accessed by removable wooden banquettes placed against the wall. All steel loophole plates have survived in situ in both of these buildings and the stone 'cheeks' of the loopholes are widely splayed inside and out to give a good field of fire.

The upper timber floor is positioned 850 mm above the loopholes, with a parapet one metre high. The shallow-pitched 'umbrella' roof of corrugated iron, which is present on the Dewetsville blockhouse, is raised some 600 mm above the parapet and oversails the outside wall face, thus providing an unobstructed view for observation and defence all around. The author was unable to gain access to the inside of the Dewetsville blockhouse in order to view the upper floor and roof design, but the surviving wall posts, fixed to the inside of the parapet on the south-west blockhouse, suggest a similar arrangement to that of the standard pattern blockhouses. The absence of galleries or bastions and, indeed, the hexagonal plan itself, would have made it impossible to provide flanking fire along the base of the walls, placing this design into the category of blockhouses which were only suitable for a garrison town where military back-up was available immediately.

The hexagonal blockhouse at Dewetsville, Aliwal North.

The 'one-offs'

In addition to the 'series patterns' described above, there is a wide

variety of masonry blockhouses of which there appears to be only one surviving

(or demolished) example.

The blockhouse at Warmbaths [NP] is a curious hybrid. Measuring 6,15 m square externally on plan, it was originally two-storeyed with two loopholes in each wall on the ground floor and a first floor entrance facing the railway line (as in the standard pattern). The first floor walls are pierced by two loopholes on each side of the entrance, four loopholes and a window in each of the other two walls (a standard pattern variant). At roof level, there was a somewhat flat, double-pitched roof, which would probably have been covered with corrugated iron, and crenellated parapets 1,8 m high (typical of a Magaliesberg pattern blockhouse). These arrangements were altered later when a doorway and window were inserted in existing loopholes on the ground floor, the lower part of the upper doorway was closed up to form a window, the parapets were extended upwards in plastered brickwork, and a pyramidal corrugated roof was added with a weathervane and matchboarded ceilings. The steep ladder staircases appear to be original and, for once, the central floor traps are absent.

The blockhouse at Warmbaths.

At Krugersdorp, Fort Harlech [G] is situated in the suburb of Monument Township. This double-storeyed blockhouse is rectangular in plan (8,65 x 6,25 m externally) with the corners cut off. It is flanked by two single-storeyed angle bastions, also each with the outer corner cut off, though they are of a more generous size than those in the Vereeniging pattern. The roof of the main building appears to be a more recent addition, and those of the bastions are missing. The upper floor of the main building is also gone, although the wall offset is visible.

Fort Harlech, Krugersdorp

showing the angle bastions to the left and right.

The example at Prieska [NC], is hexagonal in plan and the most notable feature is the bulbous profile of its walls which are thickened by sloping offsets to a maximum of 1,4 m at the base. It is entered through a low arched passage at ground level, which is extended internally through a masonry sub-structure which had a vertical sliding door at its inner end and supports a square galvanised water tank to one side of the entrance passage. The Prieska blockhouse is defended by three loopholes in each wall at a height of 2,5 m, thus necessitating wooden banquettes for access. The loopholes are unusual in that they are formed of flat galvanised sheet metal fixed to a wooden frame right through the wall, 'waisted' in the middle on plan and angled steeply downwards.

The Prieska Blockhouse.

The shallow-pitched timber 'umbrella' roof sits inside the parapets and is largely original, the corrugated iron covering and parapet walls with three upper loopholes per wall (for defence from the roof) having been carefully restored by the municipality, using old photographs and recollections from residents.

At Jacobsdal [FS], the single-storeyed blockhouse, measuring 6,2 m square, is unusual because of the 300 mm wide and 700 mm high wall thickening, or firing step, around the inside wall, which gave access to the loopholes, the sills of which are 2,2 m above floor level. This firing step is too narrow to have been used on its own and would have required timber banquettes to supplement the width. This is the dilemma of the single-storeyed blockhouse on flat ground; it is built single-storeyed to save costs, but the loopholes had to be set high in the walls to give a good view over the countryside and to prevent attackers from firing through the loopholes from close range. Therefore, the necessary banquettes, which were at least 1,2 m wide, would have cluttered up the interior so that the clear floor space in the centre was only 2,5 m square. The banquettes probably also functioned as bunks.

The Jacobsdal blockhouse has three loopholes per wall in three of its walls, with an additional loophole at each corner. The wall opposite the door was largely rebuilt when a wagon entrance was inserted later to convert it into a shed for the local hearse. The loopholes are lined with wooden boards and the steel loophole plates are secured in place with wooden battens. Canvas flaps fixed to the timber lintels to reduce draughts are still visible. The building is spanned by a timber truss roof covered in corrugated iron, with a gable of similar construction incorporating a centre-pivoted ventilator over the rebuilt wall and a masonry gable at the other end.

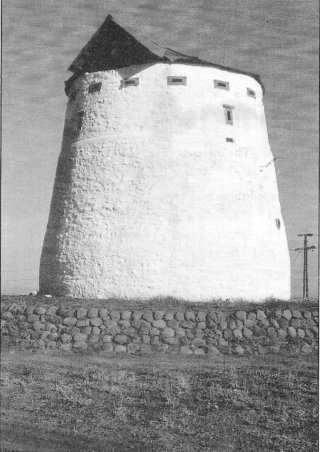

The blockhouse at Noupoort [EC] is the most idiosyncratic and impractical building of its type in South Africa. Circular in plan, with an external diameter of 8,5 m at the base, tapering to about 7 m at the top, the whitewashed stone tower is approximately 7 m high and most resembles a tower windmill such as Mostert's Mill in Cape Town. The building is featureless up to a height of 4,9 m above ground level, at which point the wall sets back 100 mm and above which there are three 225 x 75 mm cast iron air vents. Around the middle of this top stage are five steel loopholes set vertically, and near the wall top, there are a further fifteen loopholes set horizontally. The loophole plates are unusual in that they are mounted on the outside wall face and not in the middle of the wall layer as is customary, and the apertures are much larger than usual. The tower is covered by an umbrella-shaped corrugated roof, which oversails the walls slightly, and has a gabled extension facing south-east which accommodates the entrance door in a vertical, corrugated wall. The internal arrangements of this blockhouse are not known as, with the entrance being more than seven metres above ground level, access is difficult. The top floor would appear to be positioned just above the air vents, so that the defenders would kneel to fire through the vertical loopholes and stand to fire through the horizontal ones. The storage area below may be divided into two by a second floor, or it could be one deep storey.

The Noupoort Blockhouse, showing the entrance gable.

One problem associated with this structure is that the seven-metre long ladder would be very difficult to draw inside in the event of an attack and would project out of the doorway. It is therefore more likely that it would have been left in position, particularly if the blockhouse were surrounded and defended by a large garrison. In the absence of any windows in the lower storey(s), there would have been no light or ventilation there. The absence of machicouli galleries at the top would have made it impossible to protect the base against an attacking force, again suggesting that it was located in a garrison area. The author does not believe that this structure would have been built specifically as a blockhouse and considers it far more likely that it was converted from an existing windmill.

Strictly speaking, the well-known landmark at Cogman's Kloof [WC] is not a blockhouse, but it is included here as a construction of mortared stonework which shares some features with the blockhouses. Perched high on a rock above the R62 road, three kilometres south of Montagu, it measures 9,3 x 3,8 m outside. It has a simple entrance opening at the west end and 21 'waisted' loopholes formed in the masonry without steel plates. The loopholes are 700-800 mm above the concrete floor and the 400 mm thick stone walls reach a height of about two metres inside the building.

Inside the fort, near the south-east corner, is a roughly circular mortared stone platform (400 mm high), together with a drainage channel and hole at the base of the adjacent east wall, which seems to indicate the presence of a water tank and hence a roof; it is certainly hard to imagine the 'Tommies' carrying water up the ninety or so steps to the fort from the water wagon in the roadway below or the river on a regular basis. It is not known how much this building has been restored, but one would expect the entrance to have been protected by a screen wall either inside or outside.

Other demolished patterns

Several different styles of 'one-off' blockhouses which have not been

located can be discerned from photographs in museums, private collections

and books, etc.

At Elandsfontein (Germiston) [G], there was a square-shaped, mortared, double-storeyed stone building with a flat roof and crenellated parapet. The upper storey was set back to accommodate two loopholed angle galleries unusually clad in vertical corrugated iron; the entrance was two or three metres above the ground. The exact location of this blockhouse is not known.

A photograph in the collection of MuseuMAfricA shows a double-storeyed rectangular plastered building with four loopholes at the upper level, with an octagonal three-storeyed structure behind with two loopholes per wall at the top level. Unusually, the octagonal portion appears to have been built in brickwork. It was situated in the Market Square in Hopetown [NC].

Hopetown Blockhouse.

(Photo: MuseuMAfricA).

The Kaalfontein/Zuurfontein blockhouse [G] was a hexagonal three-storeyed stone blockhouse, covered by a low-pitched 'umbrella' corrugated roof with a wide eaves projection over the walls. In the photograph, the first floor entrance and access ladder and the loopholes at all three levels are clearly visible, with two officers and four other ranks posing in front, but the exceptional feature of this blockhouse must be the three bell-shaped 'shields with projecting gun barrels' positioned on each visible wall face between the first and second floor loopholes. Were these designed to scare the enemy into believing that the blockhouse was protected by Maxim guns? The site was on the outskirts of present-day Kempton Park.

Kaalfontein/Zuurfontein Blockhouse.

(Photo: MuseuMAfricA).

A small three-storeyed blockhouse at Pietersburg [NP] measured about 3,5 m square and had two loopholes in each ground floor wall, three loopholes and a window per first floor wall, a crenellated parapet and two diagonally-opposed angle galleries. It was built using large stone blocks with thick mortar joints and is portrayed in the photographs without a roof. It was the most northerly of the masonry blockhouses in South Africa, but, strangely, it is not included in either of the returns of blockhouses built in Pretoria District, although Pietersburg is mentioned in CRE Pretoria's return of 31 March 1902 as the last town on the northern line with a total of eighteen corrugated blockhouses to its credit. This structure defended the railway station.

The blockhouse on Timeball Hill, Pretoria, was a rectangular one-storeyed building overlooking the NZASM embankment and bridge over the Apies River Valley near the Fountains. The entrance was at ground level on the sloping side away from the railway, but the interesting feature is the timber/corrugated iron loopholed breastwork which surrounded the concrete flat roof, effectively turning the building into a double-storeyed one.

The Timeball Hill Blockhouse.

(Photo: MuseuMAfricA).

Identification of individual blockhouses

With so many blockhouses of similar design, especially those of the

standard pattern, it may seem at first sight that the positive identification

of a specific building would be very difficult, if not impossible. Such

identification of individual buildings is usually necessary when one encounters

unidentified photographs in archival or museum collections. Fortunately,

the author has developed reliable techniques of 'reading' the stones and

the backgrounds and, provided the old photograph is clear with as little

as possible of the building in shadow, this is not difficult.

'Reading the stones' is best done at the site with the relevant photograph, but it can also be carried out successfully using both archival and recent photographs, which show the same aspect of the building clearly. Very simply, the principle is that most stone walls exhibit one or more prominent and recognisable feature(s), such as an unusually coloured stone, or a particularly large or oddly shaped stone. Taking such features into account, it is possible to 'finger-print' a building and, if three or four prominent characteristics can be found to tally on a wall, a 'match' can be confirmed.

'Reading the background' should also be undertaken with the archival photograph on site. Mountains and rivers change little over time and can be quite distinctive features. The author recently identified a blockhouse in an old photograph as that at De Wet Stafion near Worcester, purely as a result of the unique mountain profile in the background. The blockhouse in question was built of rather featureless concrete and had collapsed so that only a fragment remained, but the backdrop was unmistakable and the remains of the blockhouse are in the correct place relative to the mountain.

Summary

The British masonry blockhouses of the South African War are the swansong

of a castle and fort-building tradition which stretches back over 1 000

years and embraces a large part of the world. No more stonework fortifications

were to be built by the British after this war. In the context of the very

sophisticated fortification technology current in Europe and the United

States of America during the nineteenth century, these are small and simple

structures, designed to counter an enemy armed with rifles and no artillery.

They served their purpose and were successful in that, whilst 'the wrecking

of the railways reached a maximum in November and December 1900',(19) it

has been stated that not a single important railway bridge was demolished

by the Boers during Kitchener's command.(20) Together with the more numerous

lines of corrugated blockhouses, they were, in a large measure, responsible

for restricting the movement of the commandos, which terminated the guerrilla

phase of the war.

As examples of stonework construction, these blockhouses are well-built and are fine specimens of the stonemason's art. The use of local stone, often quarried close to the site, produces a wide array of colours in different parts of the country, and these buildings fit in with their surroundings. The survival of so many examples testifies to their solid construction and the considerable variation of design types highlights the ingenuity and the wide degree of latitude given to the Royal Engineer officers who planned these interesting structures. They are an important contribution to the built environment and to our historic heritage and remain a highly visible reminder of the war.

What of the future? To date, some eighteen masonry blockhouses throughout South Africa have been declared national monuments.(21) Officially, this confers a degree of legal protection on these structures, as does the fact that they are over fifty years old, but this does not necessarily safeguard them against vandalism and deterioration caused by weathering. As with all such small buildings, which are not sufficiently high profile to justify a caretaker, it is often the more remote examples which survive the best. From time to time, money is voted by the National Monuments Council for the restoration or emergency repair of a blockhouse. However, funds for the maintenance of historic buildings are generally hard to find. Fortunately, some restoration work is being considered for some blockhouses which are situated on the planned routes to commemorate the centenary of the war in 1999. The author believes that the centenary events will take special cognizance of these very physical mementos of the 'last of the gentlemen's wars'.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the following organisations and individuals

for help willingly provided over the years:

The late Colonel (Dr) Jan Ploeger, who guided the author in the right direction

at the beginning of his research.

The staffs of the State Archives and the National Cultural Historical and

Open Mr Museum (NASCO) in Pretoria; the South African National Museum of

Military History and MuseuMAfricA in Johannesburg; the McGregor Museum

in Kimberley (especially Ms Fiona Barbour); the various regional offices

of the National Monuments Council; and the Library of the Royal Engineers,

Chatham, England.

Mr Tom Andrews and Mr Mervyn Emms of Pretoria (in addition to the foregoing

institutions) for granting the author permission to copy old photographs

from their private collections.

The author's long-time friends, Mr David Panagos and Mr Barrie Thomson

for assistance and company on many field trips; and the many other individuals

too numerous to mention by name for contributing pieces of information

to fit into the puzzle.

Notes and references

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org