The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

Forward

There appear to be few references to British motorcycles in the service of the Union Defence Forces (UDF), little information about them having been recorded in South African military annals. The following article has therefore been compiled largely by independent research.

Introduction

In June 1995, an article entitled 'Harleys in Khaki' appeared in the Military History Journal (Vol 10 No 1). Although Harley-Davidsons were almost synonymous with motorcycles used by the Union Defence Forces in the Second World War, the British bikes used by the UDF merit some attention, also having played a role in the war, albeit in a more limited way. These machines took their place with front-line troops and were used in ensuring the smooth running of convoys, the sign-posting of roads and deviations, and the rounding up of prisoners, as well as for reconnaissance, despatch riding and signalling related duties.

After the outbreak of war in September 1939, motor-cycles belonging to private individuals in South Africa were commandeered by the UDF, compensated for, and put into service. These motorcycles were almost all of British manufacture and makes such as the BSA, Norton, Ariel, Matchless. AJS, Royal Enfield and Triumph made up the majority of the machines in the motley collection at the outset of the war.

Prior to the war, South Africa's defence force had, in 1937, ordered only ten Nortons. This was followed in 1938 by an order for 24 BSAs and, in 1939, 177 (M20) BSAs were ordered. In 1940, 101 BSAs were purchased from the South African Police and an additional 110 Matchlesses were ordered from England. In the same year, American Harley-Davidsons were also ordered and began to appear on the scene. Being at war herself, Britain could no longer afford to supply motorcycles for export and the production of civilian motorcycles had already ceased at the time of the outbreak of war.

Thousands of BSAs, Matchlesses, Notions, Triumphs and Royal Enfields, amongst others, were manufactured for use by the British forces in various theatres of the war. The manufacturers had accepted that, in wartime, a tough and simple machine was essential; one which could withstand service use and required the least possible maintenance (as riders would often have to improvise in difficult situations). Fortunately, most manufacturers were able to produce this type of motor-cycle and simple single-cylindered machines were those in highest demand. In this context, it is interesting to note some details of the various British marques, as well as the comparatively large number of military models that were developed and manufactured during the war. Britain was committed to providing her armies with motorcycles and therefore could hardly be expected to fulfil outside orders. Therefore, these British motorcycles differed substantially from those produced for South Africa. Some details of the British bikes are mentioned below:

BSA was one of the main suppliers of motorcycles in Britain during the war, producing over 126 000 units. The models included the 350 cc OHV (only 10 000 units), and 500 cc (mainly M20s) SV.

Matchless produced 80 000 motorcycles. Preferred by despatch riders, the 350 cc OHV (G3L) model had the decided advantage of having telescopic front forks, the first British motorcycle to have this feature.

Norton manufactured over 75 000 military motorcycles, both solo and side-car models. The 500 cc (16H) SV Notions were plagued by assembly and gearbox faults and were not very reliable. The 630 cc side-car model was basically a civilian machine.

During the war, the Triumph factory at Coventry was heavily bombed and their production records were destroyed. However, they manufactured the 350 cc (3HW) OHV, the 350 cc (3SW) SV and the 500 cc (5TW) SV, all of which proved to be reliable and strongly made models.

Velocette produced a mere 5 000 units. This was a specialist bike and did not have a modern factory assembly line. The 350 cc (MDD and MAF) OHV was developed from the popular MAC civilian model and was well-liked by its riders.

Royal Enfield produced a total of over 40 000 motor-cycles. Their slogan was 'built like a gun' - very appropriate! - to which one might add 'and goes like a bullet?' Royal Enfield produced the two-stroke 125 cc (WD-RE) model, the 350 cc (Model G and Model CO) OHV, and the 500 cc (Model J) OHV. Both the latter models became famous by British standards, although their braking ability was debatable.

Ariel turned out a total of 47 500 motorcycles. Models produced were the 250 cc (OG) OHV and the 350 cc (W-NG) OHV. The Ariel was a tough motorcycle, solidly built.

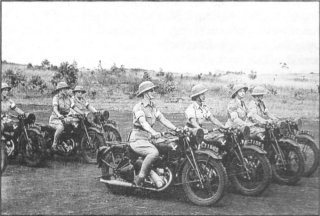

Field Marshal JC Smuts inspects a motorcycle company

in East Africa. The machines are 600cc SV M21 BSA

motorcycles. (Photo. SANMMH).

Many South African women paid their own passage to East Africa

to join the FANYs (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry), seen

here equipped with 500cc SV M20 BSAs. (Photo: SANDF).

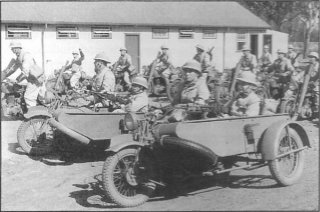

A South African motorcycle unit leaves a local training camp

in 1940, riding 500cc SV M20 BSAJS. (Photo: SANMMH)

As the United States of America only entered the Second World War after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, Harley-Davidson motor-cycles were more readily available than the British motorcycles until that time. Notwithstanding the time factor, practical considerations for the purchase of the most suitable motorcycles for the UDF were carefully weighed up. Thus the decision was taken that mainly Harley-Davidsons were ordered for the army.

In July 1940, 96 newly-ordered BSA motorcycles with side-cars arrived at Voortrekkerhoogte for training purposes. These motorcycles formed part of No 1 Motorcycle Company, whose personnel, after strenuous training, were ready to leave for the frontline. Unfortunately, very few spare parts were available for the company's impressed second-hand machines. The South African Police had also supplied some units to No 1 Motorcycle Company.

Early in 1940, Nos 2 and 3 Motorcycle companies were raised as Active Ctizen Force units, later to be formed into two companies in June 1940, with No 3 being considered as a reinforcement pool. No 1 Company travelled by train to Durban and, in August 1940, they left the Union by ship, bound for East Africa. From the port, they travelled by train to Gil Gil in Kenya, where they remained for a month, carrying out further training, long rides and manoeuvres. In September, the company left Gil Gil for Marsabit via Nanyuki, a terrible journey, as there were no roads and deep sand and rock had to be overcome. On many a stretch, they covered less than four kilometres in an hour. At times, those riding solo had to walk with their machines between their legs. Others had to ride 35 metres apart because of the immense dust created, and many collisions occurred. With the advent of autumn and the area's torrential rains, machines became bogged down in the mud and the men were all but wahsed out of their camp, forcing them to move to higher ground. They struggled for days to extricate their motorcycles from the mud and side-car machines, which were laden with Bren guns, anti-tank rifles and ammunition, required the effort of the whole patrol to move them, as they could not be ridden.

In November 1940, the company moved to North Horr, some 200 km away, and then on to Dukana, a further 140 km away, all of this once again on bad roads and in trying conditions with extreme heat and wind and driving dust storms. It was soon realised that motorcycles were not suitable for that type of terrain, but the riders persevered, braving the trying weather conditions and riding to the best of their ability, hoping for a chance of fighting. Many suffered from heat fatigue and other tropical ailments. Inadequate supplies of nourishing food and limited rations, as well as the occasional rationing of water, added to the problems experienced by the riders. Kenya was indeed a very tough country.

By March 1941. the company had made its way to Mega, once again through a morass of mud, in which six motorcycles had had to be abandoned. Nevertheless, the journey to Nanyuki continued and 800 km were covered in seven days over very difficult terrain. Further orders were received for sixty motorcycles to be railed from Mombasa for shipment to Mogadishu, whereas the other vehicles (including motorcycles) reached their destination in Ethiopia by completing the 1 600 km journey by road. Again, this was a very tough experience.

From Mogadishu, the whole company continued on a 1 800 km journey via Modun, Tijiga, Harar, Auasc to the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa (which had, by then, been captured from the Italians), where they arrived in May 1941.

Quartered in Addis Ababa for four months, the company's duties were to police and patrol the town and to maintain law and order. This the No 1 SA Motorcycle Company did admirably, laying the foundation for the newly formed Ethiopian Police Force who subsequently took over.

August 1941 was to see an end to No 1 Motorcycle Company's spell in Addis Ababa, when patrolling was taken over by the Civil Police to whom No 1 Company's drab khaki-painted British motorcycles were presented. The military achievements created with the help of the motorcycle companies in the border wars in the unforgiving wastes of Kenya's northern frontier and in the deserts and mountains of Abyssinia in the first two years of the Second World War were indeed an important milestone in the annals of the history of the Union Defence Forces.

The No 1 Motorcycle Company subsequently embarked for the Middle East in the last week of August 1941. Once there, it was disbanded and its personnel was transferred to the 3rd SA Armoured Car Battalion. Thus ended the somewhat short saga of the use of British motorcycles in the UDF. These machines were not used by South Africa in the epic battles of the Western Desert - this was left to the stronger, more rugged and imposing Harley-Davidsons of that era.

Note on sources

The article above is based on research undertaken at the South African National Museum of Military History in Saxonwold, Johannesburg. First-hand information was collected through interviews with ex-Don R' s of the period. The book, Military Motorcycles (Pictorial), by D Ansell, provided additional information and the author wishes to thank Mrs E van Rensburg of Pretoria for undertaking to source some of the photographs at the SA National Museum of Military History.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org