The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

I was a member of the 2nd Botha Regiment and, during the formation of the 5th South African Infantry Brigade at Barberton, I was attached to the brigade headquarters. The brigade slowly took shape and was converted into an efficient fighting unit under the capable direction of the brigade major, Major Carbutt, and the brigade sergeant major, 'Snakebite'.

Shortly before the 5th SAI Brigade received its orders to proceed up North, I was sent on a cadet course to the Military College in Pretoria, where I received my commission. Amongst my memories of Barberton were the skirling of the pipes of the 3rd Transvaal Scottish and the 1st South African Irish regiments, and the brass band of 2nd Botha Regiment with the holding of the Retreat Ceremony every evening.

In due course, I was drafted to Helwan Camp in Egypt, where we first came into contact with the teeming life of the Middle East in Cairo. From there, I managed to rejoin my regiment at Mersa Matruh. I was subsequently appointed as a liaison officer between the brigade headquarters and the regiment.

Amongst the many memories of life at Mersa Matruh, I recall our bathing in the Mediterranean with its powdered coral beaches, which were as soft as flour. The different colours of the Mediterranean were amazing and the desert sunsets, especially after a ghamseen (a desert sandstorm) with its accompanying dust, had to be seen to be believed. We lived in dugouts, which were lined with timber from bombed out Arab buildings and infested with bed bugs. Once, we obtained a tin into which we put Keatings powder from a 'glory' bag. We caught several of the bugs and put them into the powder, only to find that, after a week, they were still flourishing and crawling about in the powder. I also remember the nightly bombing raids by the Germans with the offbeat noise of their bombers and the whistling bombs.

In November 1941, the 5th SA Infantry Brigade was instructed to proceed on 'manoeuvres' - so-named as a security precaution. The manoeuvres ended with the brigade moving on to Libya in a south-westerly direction. On 18 November, we crossed the barbed wire barricade between Egypt and Libya. The engineers had managed to make gaps in the heavily fortified wire entanglements to enable the brigade to proceed into Libya.

Not long after crossing the border, we were attacked by bombers of the Italian Air Force. One bomber was shot down and all of its bombs exploded as it hit the ground. In my jeep, I went over to inspect the incident. A huge crater had been formed and the brigade chaplain was administering the last rites for the human fragments which were all that remained of the bomber crew.

The brigade proceeded in open formation over a front of some three miles [4,8 km]. The 3rd Transvaal Scottish was in the lead, with the 2nd South African Irish Regiment on the left flank and the 2nd Botha Regiment on the right flank of the Brigade HQ, and B Echelon bringing up the rear. Together with the New Zealanders and the Scots Guards, we formed a left flank to the 7th Armoured Division. Our objective was the relief of Tobruk. The reason for the dispersion of our vehicles was to minimise damage from air attack. Each vehicle was instructed not to follow in line with the vehicle ahead of it and to take its own path. This would prevent fighter aircraft from lining up vehicles in a machine gun attack.

We travelled under radio silence and, in order to maintain contact with the three regiments of the brigade whilst in motion, we, the liaison officers, would convey urgent messages to our respective regiments by jeep. In addition, the Brigade Command Vehicle operated what we called the 'Kirby Code'. This consisted of a pole which was visible from every angle for miles and could be picked up using binoculars. Short bars were attached to the pole at right angles and various geometrical designs were hung from these bars and the pole was rotated slowly so that everyone could see the designs. Triangles, circles, squares, crosses and other shapes formed the Kirby Code, named after Colonel Kirby, the colonel of the 3rd Transvaal Scottish Regiment. Combinations of the designs represented certain basic orders, such as 'air attack warning', 'ground attack warning' and 'brigade will halt'.

On 21 November, we arrived at Sidi Rezegh, not far from Tobruk, but were confronted by elements of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions. We were soon surrounded. The German tanks towed heavy artillery, which had been used to bombard Tobruk. These weapons were used against us from all sides. For three days the battle raged and on 23 November we were subjected to a three hour saturation barrage. I was with Colonel Mason in the forward area of the Botha Regiment sector. We were in shallow slit trenches which were only about nine inches [23 cm] deep. We were unable to dig deeper as we were then on solid limestone. We were pinned down by machine gun fire from the surrounding German tanks and heard the vicious 'zip' of the bullets, like angry wasps, just above our heads. We had lost contact with the Brigade HQ, as our field telephone lines had been broken by shell fire. Colonel Mason told me to proceed to Brigade HQ and request artillery support from Colonel White to relieve the pressure from the tanks.

I climbed into my jeep and drove to Brigade HQ, only to be fired upon. It appeared that German tanks had broken through B Echelon at our rear and had captured Brigade HQ in our midst. On my return to Colonel Mason, a shell burst right in front of me, but caused no serious damage. We discussed our position under the new circumstances. I had found a beautiful pair of Zeiss field glasses in a bombed-out German tank and I handed these to Colonel Mason. Just then, a shell burst next to us and smashed my field glasses. The colonel was heavily wounded.

A message had been passed on to us by word of mouth that German infantry reinforcements were arriving and we would have to make a dash to break out before we were taken prisoner as our position was deteriorating. The colonel's driver and I placed the wounded colonel in his staff car. I then told the driver to follow my jeep as I was going to run the gauntlet between the tanks to attempt to break out of our position. Fortunately, it was getting dark. I drove the jeep at seventy miles per hour [112 km/h] and moved the steering wheel from side to side to put the German machine gunners off their aim. The Germans used tracer shells in the poor light and there was a streak of light as each shell was fired. One of our armoured cars, which was to my left and slightly ahead of me, received a direct hit from a German tank shell and a friend of mine lost his leg at the hip. All four tyres of my jeep were shot flat and the body was riddled with holes and I continued on flat tyres. Just beyond the tanks, the jeep's driving shaft broke, having been shot through. I managed to get a lift with another vehicle and so proceeded beyond the tank danger.

There, three other officers and I halted the streaming vehicles. A mad rush would only have led us all into the hands of other German forces. I remembered, from my last look at our positions on the maps at Brigade HQ, that the 4th Indian Division was situated to the north-east of our present position. Taking my bearings from the North Star and working out mentally the angle of the bearing on the map, and then applying this angle from the North Star, I worked out the approximate direction in which we would have to proceed in order to reach the 4th Indian Division. I told the others that I would lead them there. We took only those vehicles which had sufficient petrol and abandoned the others, after removing the rotors in order to immobilise them. We had with us eleven seriously wounded, several with multiple fractures from the hips down, whose legs had been run over by tanks. We placed the wounded on the floors of the troop carriers and I led the column, which moved at a slow but steady pace, four vehicles abreast, no lights and guided by the stars. At about first light, I heard the challenge of an Indian sentry. By the grace of God, we had arrived exactly at the position of the 4th Indian Division and were able to hand over our wounded to their field medical services and doctors. I reported to the British general there and our troops and vehicles were taken over. From my previous contact with the Brigade HQ, I was able to inform the general of the situation in which the brigade found itself. He told me to call for volunteers and then to return to the battlefield to lead any other stragglers to safety. Corporal Lightfoot and seven other volunteers agreed to accompany me and we entered again the jaws of hell from which we had just been delivered.

After we had proceeded a considerable distance in our troop carrier, we saw a collection of vehicles moving towards us. Just then, we saw strips of dust as German light tanks, travelling at speed, overtook the vehicles and started to herd them away. We immediately turned due south and drove away at speed with some of the tanks following us. Fortunately, it was getting late and Corporal Lightfoot procured every ounce of speed out of that Ford troop carrier. The German tank following us fired whilst travelling at speed and there was an occasional clang as a bullet hit the troop carrier, but we were eventually able to shake them off by changing direction slightly as the light began to fail.

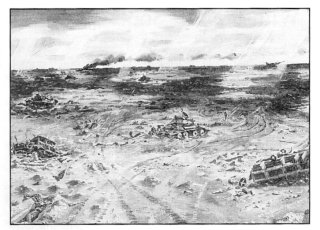

'Field of Sidi Rezegh' by Geoffrey Long. [Photo: SANMMH].

As it got dark, the Germans began using Verey lights of different colours and kinds. These were apparently being used to indicate where their various forces were operating in order to co-ordinate their movements. The lights also showed us where they were and, when we found a slight depression, we decided to park the troop carrier therein and move a few hundred yards away to some sand dunes. Using our steel helmets, we dug slit trenches in the dunes, and were able to conceal ourselves. Not long afterwards, we heard the heavy growling roar of the tanks accompanied by the squeaking of their tracks. The tanks passed quite close to us and, in the starlight, we could just make out the forms of troops with tommy guns, sitting on the tanks, apparently looking for strays such as ourselves. When the Verey lights showed that the Germans had moved away from us, we made our way back to our troop carrier and carried on in a south-easterly direction.

Just before sunrise, we came across a British water supply unit who invited us in for a cup of 'Chai'. Whilst we were talking, one of our party on the troop carrier called to us that the tanks were again approaching. We immediately embussed and went on our way, whilst the tanks overran the British water supply depot.

Later in the day, we came across a British artillery major and told him about the tanks. He said that they were expecting them and that his 25 pounders were dug in and ready. He showed us the way to the rail head, which was not very far ahead. (We heard later that the major's artillery had managed to knock out several of the German tanks.)

We arrived at the rail head. On the previous night, three cattle trucks, loaded with German and Italian prisoners of war, had been waiting to be unloaded when they had been bombed and blown up during an air raid. A gang of Indian troops had been engaged in clearing up the result that morning. I reported at the rail head and we were told that we were to be used that night to escort a prisoner of war train, containing over 1 000 German and Italian prisoners, to Mersa Matmuh. An additional number of British troops were provided to augment my few volunteers. When it got dark, we were on our way and arrived at Mersa Matruh early the next morning without further mishap. The prisoners were taken over and I met up with friends of mine from the Brigade, who had remained at Mersa Matruh when we had left.

I slept for nineteen hours and a friendly major in the Engineers attended to all my wants.

The 5th South African Infantry Brigade had ceased to exist. The Germans remained in command of the battlefield at Sidi Rezegh and Brigadier Armstrong, our brigade commander, had been flown by aeroplane to Germany.

We had gone into action with a brigade strength of 5 800 and had come out with a strength of under 2 000. The balance had been killed, wounded or taken prisoner. It had been one of South Africa's heaviest losses during the war, according to General Smuts.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org