The South African

The South African

from the memoirs of the late

Lt Col H L Silberbauer

The following is his account of the war:

It is quite impossible to describe the excitement in Cape Town when war was declared...

General Botha called for volunteers in September 1914, as the Union of South Africa had been invaded near the

Orange River. A very motley crowd turned up at the Drill Hall... a sprinkling of [veterans] from the Boer War

days... , clerks, students, advocates, judges. We were all marched out from Cape Town to Oude Molen at

Mowbray and spent some uncomfortable days under canvas, without equipment, army clothing or blankets.

Our ardour cooled off somewhat!

We were to be called 'Botha's Army', but the response was poor and they marched us off to Wynberg Camp one morning, where, to our indignation, we were told that we were to form 'B', 'E' and 'F' companies of the Duke of Edinburgh's Own Volunteer Rifles, as that regiment was under strength. That was how we became part and parcel of the Duke's and very soon were proud of that fact. Wynberg training was peculiar by modern standards. Parade ground drill, marching and PT were the only things that mattered. Discipline was not bad, but on New Year's Day 1915, only fifty men turned out on parade and some had to support others. Amongst our riflemen were the ex-Chief Justice Centlivres, Sir Murray Bisset and ex-Judge President Jackie de Villiers.

I was really pleased with myself when I became an unpaid lance-corporal, then corporal, and then a sergeant. None of the non-commissioned officers knew anything at all about Drill, Arms, Field Work or, in fact, anything at all about anything they should have known. The same applied to most of the officers.

German South West Africa

Some time in March 1915, the Duke's embarked on the SS Galway Castle for German South West Africa. We landed at Swakopmund on the remains of a pier that had been blasted by an armoured cruiser and, after great confusion and contrary orders, we found ourselves in the market square and were told to make bivvies for ourselves out of what we could find... Heat, dust, flies and general confusion were our enemies. The Germans seemed to have disappeared into the sand dunes four miles (6,4 km) away and there were light skirmishes in that direction. Now that we were on active service, we did our best to train and become efficient, but it was fortunate for us that the enemy did not attack.

We were afraid of an alleged enemy plane that, it was said, would come over and pepper us with darts, but no plane was seen or heard in that glorious campaign. Our food consisted of bully beef and very hard army biscuits and jam. The factory in Natal that had made decent biscuits had been burned down because of its German name - Baumanns.

Our next move was to guard the railway line from Walvis Bay to Swakopmund. An NCO was in charge of each blockhouse and mine was 'No 2 Walvis Bay'. We could buy food in Walvis Bay and we were also close enough to the sea to bathe and spear soles. Life, for the eight of us, was not thrilling. The sandbags, out of which the blockhouse was made, were old sugar bags and attracted flies and we all suffered from diarrhoea... We practised Morse and semaphore, but it was difficult to pass the time and no-one was sorry when we moved on to Swakopmund after 'keeping the enemy at bay' for six weeks.

One night, we had a real alarm and had to pack up at once and entrain. Unfortunately, the train took so long to get up steam that we arrived at Trekkopies just after the Germans had been driven back. I lost my knife there and picked it up between the rails some months later. In France about a year later, that knife was hit by a bullet which otherwise would have struck me in the groin. At Trekkopies that evening, for the first but not last time, I heard that most moving of all calls at a military funeral, the 'Last Post' and then 'Reveille'.

Back again we went to Swakopmund. The Germans were by then being pushed back by General Botha's northern forces. General Smuts inspected us at Swakopmund and we were keen to be in at the kill. At the end of April 1915, I became a second lieutenant. I went to Husab Wells to join 'C' Company. Husab was a very dry river bed about 100 miles (160 km) from Swakopmund. It was very hot, but better than the town. My company commander was Captain P J Jowett, red-haired, efficient and the best officer in the Duke's. He later went missing at Delville Wood in France. The other lieutenant was an elderly Scotsman called McPhail, who had come all the way from Singapore to join up with the old regiment. They were both good men with whom to serve. Their discipline was high and the men came first.

After a few weeks we marched back to Swakopmund... The German General Franke was now really on the run and the Duke's moved north. We did long, hot and tiring marches and landed eventually at Karibib, where the famous marble came from. While we were there, the news arrived that Franke had surrendered and there was great rejoicing. The regiment could not say that it had been in action, but the chaps had toughened up well, were very fit, and the discipline and morale were fine. My 'C' Company would have given a very good account of themselves if they had had the opportunity. They were the tough and rough company of the Duke's.

We had a joyride from Karibib to Windhuk (Windhoek)

with young Louis Botha, who did not much resemble his

great father. The Germans in Windhuk were very

friendly and, like us, were glad that their war was over.

Our one desire then was to get home and the song of our

troops was:

We sailed from Walvis Bay in the captured SS Professor Woermann and received a wonderful welcome in Cape Town... We were paid off in record time and I went back at once to my Articles with my father at 14 Keerom Street. The study of law and the routine of an office seemed quite wrong when civilization was at war. Yet it was hard to leave one's parents to cope. However, we weighted things up and I decided to go overseas. Several of us who had been in SWA were given temporary commissions in the Imperial Army and we sailed in the Walmer Castle in January 1916.

France

We arrived at Devonport on a real winter's day. There were about forty of us and we entrained at once for London, where we were to receive our orders from Whitehall (the War Office). Although I had many letters of introduction to friends and relatives, I stayed for a few weeks at a boarding house in Edgeware Road. There was no bathroom and, if you wanted a bath, an unfortunate little 'tweeny' had to tote the water from the basement to the fourth floor, where you got into a horrible contrivance called a 'hip bath'.

One day, I called on my mother's cousins, the Thomsons, who lived in Rosary Gardens, South Kensington. Cousin Alice was kindness itself and they sent a taxi to collect my kit. Mr Thomson was a retired Indian Civil Servant, very kind and peppery. All these folk in England had suffered the loss of sons and relatives, but they never said a word and made us feel at home.

The War Office seemed to have slipped up and could not trace my file, so I spent quite a time without pay and saw the sights of London. Eventually, young Cyril Barn told me to try to get into the Leicestershire Regiment. At the War Office, I saw the famous cricketer, Plum Warner, and he fixed me up at once. My orders were to report to the 10th (Reserve) Battalion of the Leicesters and I entrained for Rugely Station and took a taxi from there to Cannock Chase.

This was my first experience of mud. Everything was mud. It had been churned up by men and animals in such a way that it was always there. However, the living quarters were comfortable - the usual army hut, but with a coal stove.

Our training followed the usual style of the First World War and did not fit one for much. There was a dearth of trained NCOs and it took time to get to know the men - those Staffordshire lads were very reserved and it was even difficult to understand them at first. (The English certainly have more varied accents than we South Africans). There were many types - English, Scots, Irish, South Africans and Canadians. On the whole, they were a fine lot, mostly just out of school and full of life... Life in spring and early summer was passable at Cannock Chase. The training went well and I cannot say that I was itching to go to France. However, orders came early in June and I found myself on a Channel steamer at Felixtowe. As we climbed aboard, we heard the news of Kitchener's death.

The war in France had settled down to trench warfare. Terrific and gallant attacks had been made on the Germans at Loos and other places and had resulted in ghastly casualties. I think that one day at Loos accounted for as many killed as did the whole of the African campaign in the Second World War. I still cannot understand why the High Command would send men into battle, fully equipped, tired after a long march, and up against barbed wire and machine guns. And they sent them in en masse! The Staff learn slowly and the slaughter was terrible. The casualty lists filled many pages and a subaltern's life was reckoned to be about five days.

We crossed the Channel, escorted by destroyers, as the U-boats played havoc with transports all over the seas. Dick Steytler, an old friend from the South African Corps of Signals, was on board. He was with the Royal Flying Corps and is gone, crashed in France.

We were a tired and hungry lot when we disembarked at Dieppe and eventually arrived at a training camp near Boulonge. The man in charge believed in hard training and, if we were not sticking bayonets into sandbags with bloody oaths, we were forming groups of four, or listening to lectures and having pep-talks. I well remember one brass-hat trying to get us to HATE the enemy, and making our men hate him: 'You cannot fight unless you hate...' On the following Sunday, the division's padre preached a sermon, stating that 'Hatred is the brother of Fear!' At any rate, one gets accustomed to pep-talks...

In the middle of June 1916, I found myself at the front. I was posted to the 6th Battalion, 'C' Company, Leicestershire Regiment. The 6th, 7th, 8th and 9th battalions were brigaded together as the 110th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Hesse. Our divisional commander was a Count von Gleichen, a name which sounds quite, if not more, German than Silberbauer. Our commanding officer was a Colonel Challoner, (who had been a lieutenant during the siege of Ladysmith in the South African War). I believe he was killed during the Irish troubles after the War. Young Cyril Bam was in the 7th Battalion and Tony Moll, captain of the Gardens Football Club, was in the 9th Battalion. Major Gordon was the brigade major and he later commanded a battalion of the Royal Scots. After the War, he retired to Elgin, where he farmed apples at Drumearn.

We were billeted on a French family, who were very kind to us. All the male members were on active service, and three of their sons had been killed. I settled down to get to know my platoon and to learn all there was to know about the trenches. The village was not under shell fire, but our guns would fire on Gommecourt and the bang of the 9,2 has to be heard to be believed. The sector seemed to be relatively quiet and it was difficult to realise that a couple of miles away was trench, barbed wire, snipers, trench mortars and sudden death. We were rehearsing for a trench raid when, to our relief, we received orders to pack up. Trench raids are beloved of the Staff and the lads behind the line lay out what they think is an exact replica of the enemy trenches, created from aerial photographs (which were, in their infancy, quite exceptional) and from reports, and the blanks were filled in from their imaginations. The unhappy subaltern goes back to the headquarters with his raiding party and they go through the drill and there appears to be no trouble in taking the trenches, scuppering a few 'Huns', and returning with prisoners and useful information. Later on, I shall tell you how a raid really pans out!

We packed up and marched south. A fully equipped soldier carries a lot of kit: a rifle, a pack full of things (including the emergency bully beef and biscuits), gas mask, entrenching tool over his tail, haversack at his side (which can be most uncomfortable), and 60 rounds of ammunition. In addition, the officer carries his binoculars, compass and map case. Every 55 minutes, the men fall out and rest for five minutes, before continuing at an average of 2,5 miles an hour (4 km/h). At the end of the day, you have had quite enough of soldiering and wish that you were home again. Then you really hate, not fear, the enemy.

The country we passed through on the way to the Somme was very lovely and had not been touched by the War. We stayed on the banks of the Somme for too short a time and then pushed on towards Albert. There we saw the famous figure of Christ hanging from the Church. There was some legend that the enemy would never take the town while the figure hung there. Most of us were new to war conditions and the trenches at Albert were those that had recently been occupied by the Germans. They certainly built for comfort and security. Outside the trenches were many unburied dead, ours and theirs - a sight to which I never became accustomed. It is strange how impersonal these figures become, and that is just as well, or the average person would go off his head. The officer has an advantage over his men in that he must steel himself against any feeling that might impair his efficiency, or do anything that might appear at all weak in their eyes. It is that knowledge and the realisation of his responsibilities which sometimes lifts the NCO and the officer above himself.

We had no sooner settled down in those nice German dug-outs when we experienced our first real shelling. I did not like it and was never more scared in my life, but I took comfort from my company sergeant-major, who said that it was nothing to worry about and it was just bad luck if you were hit. We all stayed put, but then the Germans started to use tear gas and it was ridiculous to see a platoon of men with tears running down their cheeks. Tear gas does not cause much harm to the infantry, but the gunners hate it. Eyes soon recover and there are no ill effects. Of other types of gas, the less said the better. I never personally experienced a gas attack, but the 2nd Leicesters did, and after that they never took any prisoners - and they were justified in that. War is a rotten business and you might say that it is just as bad to kill a person one way than another. Men get their limbs blown off and the most horrible wounds from the recognised gentle methods of warfare, but the sight of soldiers who have been gassed is awful and it is an everlasting shame on the Germans for having used such a loathsome weapon.

Suddenly the air was full of rumours of a breakthrough and our hopes were raised by the presence of the cavalry, who would romp through after us and run the enemy back to Berlin. Early in July, Mametz Wood had been taken, but the losses had been very heavy.

We were assembled and our new divisional commander addressed us. The army commander, General Rawlinson, then told us that our task would be to capture Bazentin-le-Petit village and wood and that we were to hold it at all costs. I suppose he thought his address was inspiring, but I took a poor view of it!

All this time the battle seemed near. On the night of 12 July, we marched up to our launching place and were guided through the outskirts of Mametz Wood. The dead were everywhere and the men became tired and depressed as we slogged towards the battle. However, once we were in position, a kind of excitement gripped us all and most of us acknowledged afterwards that we had wondered what it would be like to be dead.

Our task was to take three successive lines of trenches and the artillery barrage would lift at definite times to allow us to go forward. The noise was infernal and bewildering - darkness was shattered by ghastly flashes of light and explosions erupted all around. Trees, men, earth, all seemed to be blown to bits around us, but so far, 'C' Company had suffered no casualties. We all crouched in the grass waiting for zero hour at 02.15. The night was mild, but the men were shivering and sweating. Our last meal had been at 19.00 the night before.

All watches were synchronised and zero hour was near. Then our artillery crashed down and I never imagined that such a row was possible. I suppose 'hell let loose' almost describes it. The Germans also increased their fire, and casualties mounted. We were not allowed to do anything for the wounded - that was the stretcher bearers' duty... Their work, and that of the doctors, was a revelation to me of endurance, kindness and sheer bravery.

At zero hour, the barrage lifted and forward we went! Our captain was killed almost immediately. I thought one had to dash ahead as in a story book charge, but soon realised that that was no good. The main rule was to keep the men together, to be with them and to lead them to the objective at a steady walk, or perhaps a trot. The shelling was very heavy - shrapnel and high explosives - but we arrived at the first trenches in fairly good order, to find the enemy gone.

I collected my platoon and a few stragglers from other units and waited for the next jump. On time, the barrage lifted again and on we forged, but now machine gun bullets started to inflict heavy casualties. Despite the fact that daylight was near, it was very difficult to keep in touch in a wood that was being blasted by both sides at once - fallen and falling trees were everywhere.

We struggled on and now began individual fights with stray enemy, most of whom seemed quite bewildered, although the usual brave and tough types had to be dealt with. One of our officers was badly wounded, but refused to give in. I soon lost touch with him and heard later that he had been killed. Gallant deeds were being done all around, but in the chaos there was little time to note special eases, especially names, as I was new to the battalion and at the time knew very few of the officers and men.

We - what was left of us - pushed on to the last objective before the village, but came under terrific fire from our own side, as well as from the enemy. I found out afterwards that this was due to one of those mistakes that should not happen, but do. The barrage on a certain line had been marked 'cancelled' on the infantry maps, but not on the artillery ones. That was one of my nastiest moments in the battle.

We were now out of that nightmare wood in what was once a village - the village of Bazentin-le-Petit, and the day was 13 July. We had achieved our objective, and fondly believed that the Germans were on their way back to Berlin. We received orders to consolidate. The village was a shambles and nothing remotely resembling a house was to be seen. Here I came across an old friend from Hamilton's, Toby Moll, who told me that Cyril Bam had been killed. No trace of him was to be found. Soon after this, Toby was hit by shrapnel when he was quite near me and I saw at once that there was no hope. It was hard to see Toby go - everything else was impersonal, almost unreal, but with Toby one was up against it.

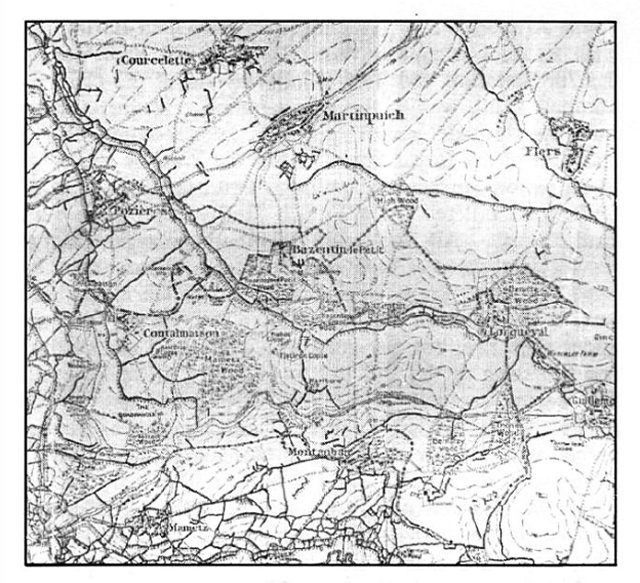

A map of the area, showing the proximity of Bazentin-le-Petit to Delville Wood. (From The Times, 2 August 1916)

The enemy appeared to be preparing for a counter-attack, and I found myself enfiladed from the right flank, so I pulled the men back to better cover in the village.

We were able to stop the Germans with our Lewis gun. The men's rifle shooting was bad. One lad was firing at the Germans, who were fifty yards (46 m) away, and his sights were set at 500 yards (457 m). But we held the enemy and then, to my joy, fresh troops (the Warwickshires) advanced on our right. The Germans saw them and ran, while we gave them many bursts of erratic fire to speed them on.

Despite the casualties we had suffered, we felt that we had to chase the Germans right out of Bazentin and up we got and chased after them. I had not gone far when I felt a whack! against my leg and heard a bullet ricochet off me in a peculiar way. I found out afterwards that the big steel knife that I had lost and later found at Trekkopies, had taken the impact. It was in my pocket over my groin! But I did not get much further after that, as another bullet drilled a very neat hole through my elbow. The wound did not hurt very much at the time, but it made me very angry and I felt like taking on the entire German Army... for a few minutes. Then I began to feel finished, as blood spouted all over the place. I took some coca tablets which made me feel dizzy and one of the lads tied a very tight tourniquet above my elbow, while I held my hand above my head, hoping to stop the bleeding. Then the stretcher bearers arrived and took me away...

The less said about the First Aid Post, the better. It was too grim for words and the doctors were overworked and under fire practically all the time. From there, we went to the Casualty Clearing Station and then a nice clean train, run by 'Quakers', evacuated us to Rouen Hospital.

It was pleasant to be in the hospital after the battle, but I wondered what had happened to the others. I heard later that only eighty men of our whole Brigade were not casualties and that every officer, except for the quarter-master, had been killed or wounded. In the bed next to mine was a Lieutenant Liefeldt, who had served with the South Africans. His face was black with powder burns, and very swollen.

I was classified as a 'walking case', but collapsed on the way to the hospital ship, Asturias (which was later torpedoed), owing to the amount of blood that I had lost. Our arrival in London was overwhelming. I was taken to London General Hospital No 1 and the nurses there were the nearest approach I am likely to meet to angels. The casualties in our ward were grim and heartbreaking and there were many sad and trying scenes there. One felt that the relatives often suffered more than the soldiers.

One fine day, Mother's cousin, Mrs Alice Thomson, came to visit me with her niece, Molly Barrow, who had been a nurse at Le Touquet. It was arranged that I should go to the Barrows at Iver Heath, near Uxbridge, to convalesce. In due course, I arrived there and met my second cousin, Col William Barrow. Mother's aunt Mary Honey had married a Barrow of the Indian Army in c 1850, and his son, this same William, gave me the old man's sword which he had used in the Indian Mutiny. William's brother, Lt Gen George Barrow, was with the 1st Army in France. He later became adjutant-general in India, where I met him in 1918, when he was Northern Army Commander. The Barrows made me feel at home and we enjoyed many pleasant jaunts on the Thames with Molly's sister, Joan. My arm was not good for punting, but I could ride a bicycle.

This interlude lasted about three months and then I received orders to report to the 3rd Reserve Battalion at Patrington. That was a miserable place, near the mouth of the Humber, but when I arrived I found that the 3rd Reserve had regular army officers and I began to consider the Army as a career. Col Cowley told me that applications would be considered for the Army in India and that, if I applied, I could go out to India after the war. I applied and wondered what the outcome would be.

The stay at Patrington was short and over to France we went. On the way, I heard that the odds were unfortunately against joining up again with the old battalion. After the usual trying French train and bus journey, I found myself at Battalion HQ, outside Bethune in the Loos area. The country was not pleasant to look upon and, as one approached the frontline, nasty noises became too frequent. We were in trenches outside what had been Vermelles. Apart from the Adjutant, I was the first Leicestershire casualty to return to the front. The rest of the officers were drawn from the North Staffordshires, the South Staffordshires and the Sherwood Foresters.

It was late September, but the weather was still good. I knew nothing about trench warfare, but was soon to learn a lot! A line of trenches ran from the Coast of Flanders to somewhere in Switzerland and, in some cases, the enemy trenches were no more than 30 yards (27 m) away from ours. A few hundred yards behind the front line was the support line, with deep dug-cuts, comparative comfort, and some freedom from mortar fire. Some 300 yards (270 m) behind that was the reserve line, and you spent three days in each.

The communication trenches were very deep and reliefs were always fair game for the enemy, so these were done quietly at night. In one sector, the enemy was always aware of the relief and the Staff could not determine how he received his information. One day, some bright chap spotted a Belgian who was ploughing on a hill nearby with two white horses and the next day he was seen with one black horse and one white horse when the relief was due. He was shot.

The HQ dug-out in the reserve line was reasonably comfortable, by trench and mud standards, and was almost level with the surface. The Adjutant told me to take command of 'A' Company, with the temporary rank of captain and off I went with two guides to find the company HQ. We wandered up winding communications trenches marked at places with notices 'Keep down, Snipers' and, after about twenty minutes, arrived at the front line, some 50 yards (46 m) from the Germans. Company HQ was down thirty steps and was an evil-smelling place, lit by guttering candles stuck in bottles.

Taking over was quite a task as I had to check rockets, ammunition, rations, etc. This done, I went on a grand tour of the front line, which happened to be relatively quiet and in good order, with well constructed bays and strongpoints. Gas sentries were posted at intervals to give warnings on Klaxon horns. I hoped that the Germans would keep quiet for the next three days.

On the way back to the Coy HQ, I was watching a rifle grenade being fired, but it burst on the rifle. I got two bits in my face, and my left ear was never quite right after that. The sergeant who had fired the grenade was badly wounded, a corporal who was coming around the traverse got a bit in his chest and an officer nearby received a piece in his ankle. Being the least hurt, I went back to report to a very annoyed Adjutant. The correct way of firing a Newton Pippin grenade was with a lanyard tied to the trigger and the puller and others under cover. Apart from being a bit sore, I was not badly wounded and began my three days in the front line.

It was a ghastly existence there in the middle of what remained of the Loos battlefield. The place was unhealthy and stank. Everyone had to be on the alert all the time and boots were never taken off during the three-day spell. In wet weather, the men had to parade in the support line and rub their feet with whale oil.., a nasty smelling process. Platoon commanders had to ensure that his men's feet were healthy.

I had never believed that rats could grow as big as large cats. They were loathsome creatures and had no fear of humans. They would squat on the dug-out table, looking at one with a speculative, greedy eye and, keeping just out of reach, would snap up anything, including candles. We knew too much about their main diet, and they gave us the creeps.

The most unpopular men in the front line were the light mortar and Stokes Mortar 'wallahs'. They would turn up and let loose their infernal machines at the enemy, and then disappear. The result was that the Germans got annoyed and their mortars would throw 'rum-jars' and other horrible things at us. You can see an approaching 'rum-jar' and dive for cover, but the aerial torpedoes arrived without warning and a steady drain of wounded was the result. The 'rum-jar' made a shattering explosion and the trench had to be repaired where it hit - always after dark. I saw one sentry, who should have dived down into his dug-out, frozen with fright, gazing at a 'rum-jar' which had landed in the trench next to him. It was a dud. (The engineers would come along later and dispose of these duds). The Minenwerfer is a superior trench mortar, about two feet (60 cm) long and six inches (15 cm) thick. They were usually aimed at targets in the back areas and, if a gun pit was hit, it was the end of gun and crew.

At night, everyone was on the alert in anticipation of trench raids. It was a ghostly vigil to stare across No Man's Land, through barbed wire, with a few remnants of humans out in front. All was silent... Suddenly a flare would shoot up into the sky and drop slowly, flickering, to earth, lighting up the nightmare torn ground; machine guns would rattle and dull crashes from mortars would shake the world. Suddenly, it would be quiet again, for a while, until the sentry thought that he saw something (or perhaps he did see something) and bursts of rifle fire would break out and all would be hell again. One of our patrols might have been out in front and we would have had to be very careful not to shoot them. Everyone was on edge for those three days in the front line.

We were not sorry when our relief arrived and we could return to the support line. Officers were on the go, night and day, visiting and inspecting trenches and cheering the men - there was nothing like trench warfare for sapping morale. Then we would return to the relief trenches with billets (if we were very fortunate), hot baths, clean dry socks and a bit of spit and polish to brighten us up.

The constantly abused Royal Army Service Corps worked wonders and, in our static front, the food was good and plentiful. When possible, the dixies were brought up in straw-lined boxes to keep the food hot and we often had good bacon, meat, tea and lots of stew, and plum-and-apple jam.

Nothing much happened in October - all seemed quiet and we were able to visit Bethune. I was sent on a ten day Lewis gun training course, enjoyed it and returned knowing a lot about that temperamental weapon. Then came winter and the trenches were soon rivers and pools of icy mud. We lived in cold clay mud and feet suffered from perpetually wearing gum boots. One horrid night, on a lone visit to a forward sap, mortars began falling about me and it was impossible to move out of the sticky mud of that Hohenzollern Redoubt. It was a nasty moment, being stuck and hearing 'rum-jars' coming in our direction.

We had a pleasant diversion when my company was sent to a village called Nouex-les-Mine to help the Engineers. Madame and her daughter, on whom I billeted, got all the mud off my uniform and it was a joy to sleep in a bed again. The men had to go forward every night to dig a tunnel towards the Germans. At the end of that tunnel, much explosive would be placed one day and a 'mine' would erupt under the Germans. Then our men would have to dash forward and consolidate a position on the far lip of the mine crater. That is, of course, if the enemy did not hear us through his instruments and counter-mine, causing our crowd to go up instead.

Looking back on these happenings, the futility and imbecility of it all seems obvious, but it is dangerous for a soldier to think along these lines. Your task is to scupper the enemy and you must be satisfied that that is all that matters. Your country is at war, and your enemy is in the same position.

I was sorry when the fortnight with the Engineers ended and we returned to 'Old Boots Trench' and 'Picadilly Circus'. Then we were raided. Our sentries sighted movement and let loose at once. The Germans (about thirty of them) did not expect to be seen so soon and made a dash for the trenches and managed to get right through the barbed wire. By then, we were all awake and bombs flew about, revolvers barked, rifles cracked, bayonets stuck and suddenly all was clear again and the enemy scurried off across No Man's Land followed by the usual rain of erratic shooting. They left two killed and some wounded behind. HQ were pleased, but we never heard if Intelligence got any information from the wounded. Raiders, of course, leave everything that might identify their unit behind.

The Northumberland Fusiliers on our flank were not so successful. One night, the enemy got into a sector of their trench and quietly removed all the occupants of a deep dug-out, without a shot being fired. No one knew how it had happened, but we guessed that they must have bluffed their way past a sentry and then surprised the sleeping dug-out. HQ were not pleased and made life a misery with new security orders.

My greatest mistake occurred the night I was ordered to send up three practice green rockets to test Artillery co-operation. I had never fired a rocket before and jammed the stick well into the clay. Of course it could not go up and made a glorious blaze right outside the Coy HQ. The Germans must have thought a special sort of 'hate' was on and started shelling the spot with all sorts of nasty stuff.

It was about this time that many of our Somme wounded started to trickle back to the Regiment and quite a few were sporting Military Medals and Military Crosses. I was glad to see them as I cannot say that I was really happy with the new crowd - they had a different outlook, different ideas on essentials and one is very near the other four officers of your company in trench warfare. By this time, an officer with a rank senior to mine had arrived and I became a platoon commander again with the rank of 2nd lieutenant. One day, we were inspected by Maj Gen George Barrow, on the Staff of the 1St Army. He told us that we would be out of the line by Christmas and he invited me to see him at 1st Army HQ. A car arrived for me near Vermelles and I went off in style, taking care that I was correctly turned out. I was glad to have had that opportunity, because I was able to see for the first time how desperately hard the Staff worked and how very frugal everything was at HQ. General Horne, First Army Commander, came in and poured tea into several tin mugs and, despite all his responsibilities, relaxed for a few minutes and seemed genuinely interested in the 2nd lieutenant from South Africa.

We were taken out of the line for Christmas to a village called Auchel, where we did not hear the sound of battle at all. The officers were comfortably billeted, as were the men (who, in their larger numbers, were in barns). I had a stuffy room and found the manure pit around which the house was built, a bit strong. The pit was a big, deep square of some 25 ft by 25 ft (7,6 x 7,6 m) and full of liquid manure.

Christmas Day was the occasion for a big feast for the men in the Town Hall and the officers and senior NCOs waited on them... I suppose they appreciated it, although a Staffordshire miner seldom shows any sign of fear, distress or gratitude.

I was forcibly struck by the very low standard of education amongst the rank and file. We noticed it in censoring their letters. Many of the men would only write: 'Dear Jane, I opes you are in the pink as I am. Wish we ad some good old Burton' or words to that effect. They were a good lot and were devoted to their families - very seldom were they led astray by the French ladies.

Auchel was too good a place to allow us to remain there for long, and we were sent north to the dreaded Ypres Sector. By then, it was really cold. We landed up in a little frozen village in Belgium called Houterkerk and carried on training. My attempts at skating and ice hockey resulted only in many bruises. Basil Melle, the Springbok, played in a rugby match on a frozen ploughed field.

It seemed that we were sent up to that sector to deceive the enemy - we were kept marching along those paved roads every day to give them the impression that we were massing for an attack. Then, hey presto! our cunning army would attack in quite another place and we would all be on the way to Berlin. The idea may have been sound, but it did not appeal to the men who had to do the marching.

After a few weeks of this jolly marching and counter-marching, we returned to the Hohenzollern Redoubt and into practically the same sector of trenches that we had left before Christmas. Things were not too bad during February and early March as everything was frozen stiff, including the mud, but then came the thaw. Sandbags burst and mud and slush were feet deep. In places, it ran over the tops of our gum boots, thigh, and was awful.

HQ decided that they wanted to know something about our opposite number and the only way to find out was to send out a raiding party. If you were lucky and came back with a few prisoners and papers, they could get an idea of the enemy troops in that sector and plot the enemy divisions with some accuracy. Fifteen men and I spent a few days studying the enemy's trenches (reconstructed) and familiarising ourselves with the layout.

The raid was set for 02.00 on a not too dark night and adjoining sectors were warned that we would be out in front. We crawled through a space in our barbed wire and slithered through the mud and muck towards the German line. All was quiet. We kept close together and hoped that nobody would develop an awkward cough, as it was apparent that we had not been spotted. The German wire looked nasty, but after ten minutes we found a weak spot where one of our mortars had loosened things up a bit. With wire cutters, we worked our way forward, and dropped into the enemy trench, scratched but happy. Half the party under the sergeant went to the right and I took the other half to the left. We were to rendezvous in thirty minutes if we did not bump into anything and, if we did, we would lead our parties back independently. We expected to strike something soon and felt that we knew the way - the practice trenches were, after all, fine reproductions of the real thing. We had not gone far when we heard voices and tension grew as we crawled towards the sound. Around a traverse were two Germans, talking softly to each other with not a care in the world. If we could knock them out without a sound, our luck would be in. The trouble was that it was difficult for two of us to go forward together. A corporal and another very tough type were to do the coshing, and their approach was faultless - neither German knew what hit him and both were knocked cold. We left two men with them and hoped that an officer patrol would come along so that we could catch some big game.

We then moved down a side trench that might lead us to a dug-out and were getting along nicely when the quiet was shattered by a bang on our right. There was no doubt that the sergeant's party had stirred up something and our job was to get back at once with our prisoners. Flares started to go up and generally the place was becoming most unhealthy.

Arrangements had been made that, in the event of a flare-up, our Artillery would put down stuff nearby to distract the enemy. In the dark, in the confusion, we made our escape and, to my great relief, the sergeant's party came running along just as we arrived at our break in the wire.

We did not crawl back this time, but floundered across that 50 yard (46 m) No Man's Land as best we could. After about twenty yards (18 m), the Germans spotted us and bullets zipped around, but fortunately nobody was hit. A flare fell among us and lay doggo until it went out. Then on, through our barbed wire and into our trenches we went, where we were received with joy by our comrades.

I went to the Battalion HQ with our two prisoners, still unconscious, and reported. The two Germans recovered, but probably had splitting headaches for months afterwards. Whether Intelligence was able to procure any useful information, I do not know. I always felt that a little gesture, like letting the raiders know whether or not their raid was worthwhile, would have been appreciated. Raids were not fun!

From beginning to end, the raid took exactly fifty minutes. We suffered two casualties. Two men fell into an old latrine pit and could not rejoin their platoon until they had gone right back to the baths and had an entire change of clothing. They took some time to live that incident down!

The War, at that time, was not going well. The campaign in Gallipoli had failed and the U-Boats were on top. There was little to cheer us up. We were handicapped by the great wastage of young officers and by the lack of trained NCOs. It was interesting to see how a young eighteen year old, straight from school, took charge of veteran men. So many of these lads were born leaders and that characteristic was instinctively recognised. There were a few duds amongst the officers but, on the whole, they were a grand lot and few lived long...

Life in the trenches continued and the great thought was a spot of leave or, better still, a 'blighty' wound that would not hurt too much and might give you a few months at home. To us from overseas, home was very far away. The Army Post Office never disappointed us and letters arrived daily with the rations. The eagerness with which letters were awaited was pathetic to see and there were very few on the Home Front who let their men-folk down. Most of the men gave far more thought to religion than they would have under normal conditions and a good padre was worth a lot.

Towards the end of March, when rumours of a contemplated push began to be circulated, we expected much from the Tanks. These had not come up to expectation on the Somme because they had been put into action too soon and the conventional general was not keen on this new idea. Had the tanks been properly tested and perfected, they would have run right through the Germans.

Aircraft were scarce and we seldom saw any. Far away, at times, there would appear a few 'planes and then there would be some wholly inaccurate ack-ack fire, but we never saw a fight and were never bombed or machine-gunned from the air.

One filthy day, I received a note to report to Battalion HQ with all my kit. Thinking it was just another course, I 'trekked' off and did not bother to say good-bye to anyone. At HQ, the Adjutant asked me what I meant by trying to get out of France and into the Indian Army. I replied that I had no idea what he was talking about, but that I certainly would not mind getting out of France. It appeared that my application at Patrington in September 1916 had been approved and that I was to report at once to India Office in London for an interview.

The cattle truck, Cheavaux 12, Hommes 40, which transported me to the coast, crawled along far too slowly, but I was in London two days later and was welcomed back at Iver Heath by Joan Barrow and her parents.

I reported to India Office with about forty others and had to undergo a stiff medical test. The interview was an ordeal and I found myself in the august presence of another distant relative, General Sir Edmund Barrow, KCB etc. All went well and I was told to enjoy myself until I received sailing orders.

It was at this time that U-Boats were at the peak of their success, so sailing orders were naturally very secret, but after a month of waiting, I was told to report to Devonport. There I boarded the RMS Walmer Castle (now a troopship) with 300 other officers, none of whom I knew, but I got to know them all after a few weeks at sea. Amongst them was the youngest major in the Army, Major Hartshorn, DCM. He later became a brigadier and officer commanding the Transvaal Scottish in North Africa, where he was awarded the DSO. He had lost his left hand at Gallipoli.

Officers had cabins and lived in comfort, but this did not apply to the men. The ship first sailed west, then north, then south-west, then due east and we put into Freetown, where our destroyer escort left us. We had some idea of the toll of the U-Boats; not a day passed in which we did not see wreckage in the sea.

After a week in Freetown, a place of mosquitoes and general discomfort, although a pretty tropical port on first sight, we sailed due south and you can imagine my mounting excitement as Cape Town drew nearer. Some time in May 1919, Table Mountain could be seen rising from the sea and that was a wonderful moment. We docked and, who should be standing at the bottom of the gangway but my brother, Ivan. He soon had me ashore and home to Mount Leon, Tamboers Kloof. I will not attempt to describe my joy of getting home. It seemed like a dream and I felt I might awaken at any moment and find myself back in the mud and filth of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. I was allowed to spend the night ashore and the next day the ship carried us to Durban, where I heard that we would have to wait about ten days for transport to India.

Lt Col H L Silberbauer joined the Indian Army and served on the North West Frontier in the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles. He married Miss Nell Steytler while on leave in South Africa in 1920. In 1922, Silberbauer retired from the Indian Army and re-entered his father's law firm, eventually becoming a senior partner. During the Second World War, he rejoined the Duke's and served in Abyssinia and North Africa. He was Mentioned in Despatches and was awarded the Military Cross. He returned to the Union on leave and was refused permission to return to the front owing to his age, but he was later requested, by Maj Gen I P de Villiers, to command the 10th Cape Corps on Robben Island. He died in Cape Town on 29 June 1965 at the age of 73.

While the Bellman hangars were certainly not considered ideal for the purpose of housing a national military history collection, and their erection on the site had resulted in some vociferous criticism from local residents, who found them to be unsightly metal structures and ordered their removal (28), they have become the central (and permanent) exhibition halls at the Museum. In the months leading up to the official opening, the hangars were painted and panelled to provide a more pleasant setting for the exhibits and, on 8 April 1947, the Museum gates opened to the public for the first time.

It was against this background that the South African National War Museum was officially opened at its present site in a ceremony which began at 10.30 am on 29 August 1947. Between 200 and 300 invited guests were seated in the open area between the two Bellman hangars and addressed, firstly, by the Chairman of the Museum's first Board of Trustees, Brig F B Adler, who delivered a fifteen minute speech on the history and objectives of the Museum. This was followed by the opening speech by General Smuts (reproduced above), and then a speech of thanks by the Mayor of Johannesburg. After the speeches, the guests were invited to have tea in a marquee that had been erected on the Museum grounds for the opening, after which they were encouraged to view the exhibits.(29)

In December 1947, the Board heard that the long-awaited army hut for office accommodation had been donated by the Quartermaster General through the War Stores Disposal Board. '[The Chairman] had inspected and approved of a hut in Hector Norris Park and as soon as official permission had been given by the City Council for its erection, the hut would be taken down and re-erected by the Public Works Department. The hut was large enough to accommodate the office, library, records, and the caretaker, and he suggested that future meetings of the Board might be held therein.'(30) It is quite fitting that this army hut (which still serves as the administration section of the Museum) and the two Bellman hangars have, over the years, become exhibits themselves, thereby adding to the historic atmosphere of the Museum. The exhibits on display in 1947 formed the nucleus of the collection which exists at the Museum today, which has grown into a fine record of South African military history.

While grand plans were made in the late 1960s and early 1970s to provide a spectacular and more suitable building for the country's first national military history museum, these plans never materialised.(31) Instead, the existing structures at the Museum have been upgraded and put to their best possible use in beautiful surroundings. Displays have changed over the years, additional buildings have been constructed, and today the Museum also serves as a most unusual and interesting venue for conferences and other functions, which are regularly held in the newly completed Capt W F Faulds VC, MC Centre, or in the Dan Pienaar Gun Park.

References

6. Bellwood, 'Our War Museum Will Preserve The Tradition Established

By Our Fighting Men'.

7. W A Bellwood, Capt 'The South African War Museum: Preserving

proud traditions', in The Nongqai, September 1944, p 1045.

8. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'. This document mentions that on 13 May

1942, even before the Liberty Cavalcade, a General Purposes Committee

had already resolved to store the collection in Johannesburg.

9. From the speech by the Mayor of Johannesburg at the official opening

of the Museum on 29 August 1947, thanking General Smuts for his

speech. A copy of this speech is kept in File 069(68) SANWM 'File

4: Origin & History, Opening Ceremony'.

10. From the speech of the Chairman of the Museum's first Board of

Trustees, Brig The Hon F B Adler, MC, VD, ED, during the official

opening of the Museum on 29 August 1947. A copy of this speech

is kept in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin & History, Opening

Ceremony'. See also Report, 1947-1948, 'Origin and History', in

South African National War Museum Annual Reports, 1947-1957, held

in the Archives of the SA National Museum of Military History.

11. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'. A copy of this letter can be found in

File 069(68) SANWM.

12. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'.

13. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'.

14. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'. In a handwritten note, General Brink

added that the use of the word 'Union' in this paragraph had been

used later by some to restrict the scope of the Museum to the

post-1910 period. He was probably referring to Mr R F Kennedy (Acting

Director of the Africans Museum), who sat on the Advisory

Committee and the War Museum's first Board of Trustees as a

representative of the City Council and was adamant that the scope of

the Museum should be limited to the Second World War to avoid

possible competition with the Africana Museum, which already

collected information and material from all the earlier wars.

15. Bellwood, 'Our War Museum Will Preserve The Tradition Established

By Our Fighting Men'.

16. South African National War Museum Annual Reports, 1947-1957,

Archives, SANMMH. The 'Objects and Functions' of the Museum are

listed as follows:

'TO provide a permanent and tangible record of the efforts,

sacrifices and heroism of the men and women of all its races in

defence of the Union of South Africa; to foster national pride in their

achievements, and to maintain the traditions which they thus established.'

'TO display exhibits which will record the traditions of past and

present units of the Union Defence Forces and other services which

assisted in the Union's efforts in time of war.'

'TO collect and preserve material for the above objects and for the

use of historians and students of military history.'

'TO educate future generations towards a realisation of the

wastefulness of war and its disastrous effect on civilisation, and to

emphasise the necessity of eliminating all possible causes of strife

between nations.'

17. Speech by the Mayor of Johannesburg at the official opening of the

South African National War Museum, 29 August 1947, in File

069(68) SANWM File 4, Origins & History, Opening Ceremony.

18. Bellwood, 'Our War Museum Will Preserve The Tradition Established

By Our Fighting Men'.

19. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'. On 12 October 1946, an official

notice, stating that the Museum was subject to the State-Aided

Institutions Act of 1931, appeared in The Government Gazette.

20. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'.

21. 'Brief history of the South African National War Museum' (1968), in

File 069(68) SANWM.

22. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'. See also the Minute Book which

Contains the minutes of the meetings of the Museum's Board of

Trustees, 25 November 1946 to 11 August 1952, and South African

National War Museum Annual Reports, 1947-1957, both held in the

Archives of the SA National Museum of Military History.

23. 'Memorandum: Historical background of the establishment of the SA

National War Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin &

History, Opening Ceremony'.

24. Copy of the text of a pamphlet for a first day cover produced to

commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Museum on 29 August

1977, in File 069(68) SANWM.

25. Copy of the text of a pamphlet for a first day cover produced to

commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Museum on 29 August

1977, in File 069(68) SANWM. According to the 'Memorandum:

Historical background of the establishment of the SA National War

Museum', in File 069(68) SANWM 'File 4: Origin & History,

Opening Ceremony', there were various reasons for the name change.

In making the decision to change the name, the Board considered the

new name to reflect more precisely the educational role of the

Museum in teaching military history. Furthermore, it was felt that the

old name unfortunately suggested that the Museum was nothing more

than a 'bombastic display of the weapons of war' and there had also

been instances where the Museum had been confused with the War

Museum/Oorlogsmuseum in Bloemfontein.

26. 'Brief history of the South African National War Museum'(1968), in

File 069(68) SANWM.

27. Minute Book, Quarterly Progress Report to the Board of Trustees for

the months of June, July and August, 1947 (On this occasion by the

Chairman, Brig Adler - the Director of the Museum, Brig Senescall,

was off duty as a result of a serious illness).

28. Minute Book, Quarterly Progress Report to the Board of Trustees for

the months of June, July and August, 1947.

29. Minute Book, 'Addendum to Quarterly Report [for the months of

June, July and August 1947]. Arrangement for Official Opening on

29th August at 10.30 am. For the information of Trustees.'

30. Minute Book, Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees, held

in Room 77 in the Public Library Buildings, Johannesburg, on

Monday, 8 December 1947, at 2.15 pm.

31. See, for example, G R Duxbury, 'The South African National War

Museum celebrates its 25th birthday (1942-1967)' in Military History

Journal, Vol 1 No 1, December 1967. Interestingly, this journal was

first produced when the Museum celebrated its 25th year of existence

and the 20th anniversary of its official opening.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org