The South African

The South African

by D Y Saks

Recently, the long-forgotten letters of a homesick South African War volunteer were discovered in the photographic files at MuseuMAfricA. Unaccessioned and undetected, they had languished there for over forty years, and it is impossible to say now how they came into the museum's possession in the first place. The letters, seven in all, were written between 15 February and 18 September 1900 by Cyril Caesar Hawkins, formerly of the Imperial Light Infantry and later a trooper in the Imperial Light Horse. He was 22 years old at the time.(1) Four letters were addressed to his mother in Pietermaritzburg and the remainder to his sister, Edie. Apart from their human interest value, providing as they do an ordinary soldier's perspective of military life, the letters also have relevance to such campaigns as the storming of the Tugela heights, the relief of Mafeking and the capture of Barberton. Hawkins wrote with little regard for grammar or sentence construction, but apart from adding the occasional comma, minimal changes have been made to his correspondence so as to preserve its original flavour. Sundry references to family and friends have, however, been omitted.

Hawkins' first letter, dated 'Springfield 15-2-1900', is addressed

to his sister in Eshowe. A few days prior to this date, in the aftermath

of his abortive attack on Vaalkrans, General Buller had decided to move

the bulk of his force back to Chieveley, east of the railway line. Cavalry

commander Lt Col J F Burn-Murdoch was left in charge of the remainder at

Springfield, today the hamlet of Winterton, on the Little Tugela. Burn-Murdoch's

division consisted of the cavalry, York and Lancaster Regiment, Imperial

Light Infantry, 'A' Battery Royal Horse Artillery and two naval 12-pounders.(2)

At that time, Hawkins was in the Imperial Light Infantry.

He wrote:

Dear Edie

I was very pleased indeed to receive your nice long letter. There are four

thousand of us here, that's including cavalry & artillery. I am having

a good deal of trench digging and picquet duty, which I dislike very much.

The Boers are reported to be a mile off in great numbers, in fact we can

see them digging trenches... the British seem to be making no progress

whatever in my opinion. I all [sic] spare no Boers or Germans which I may

come in contact with. I shall use my bayonet freely. Give Kit my love and

tell him I wish I had never seen the ILI. At present we are keeping the

line of communication open between here and Frere... I am getting thoroughly

tired of biscuits, which are as hard as iron. I shall write soon again

when I can find time. With love to Kit & yourself'

The digging of entrenchments by the Boers (referred to in the extract) could only have been visible through binoculars. They may have been those stationed at Brakfontein, the ridge linking Spioen Kop and Vaalkrans some ten kilometres away, or possibly those on Thabanyama further west. The reference to Germans can be explained by the prominent role played by both the Imperial Light Horse and the Boer's German detachment at the battle of Elandslaagte. Being an imperial volunteer himself, Hawkins would have been familiar with this.

On 21 February, the Imperial Light Infantry were also brought across

to Chieveley and, from here, Hawkins' second letter was written on 8 March.

By this time, of course, Buller had finally succeeded in relieving Ladysmith

and much of the tension had gone out of the Natal campaign:

'Dear Edie

How is it that you haven't answered my last letter? You must have been

rather frightened when the Boers invaded Zululand and commenced looting

the different districts, just think of young Dartnell and the Magistrate

being taken prisoners, it was very plucky of them keeping the enemy at

bay for an hour but of course they had to give in when the Boers began

to open fire on them with their 6-pounder. The Scouts have been having

a rather hard time in their estimation but I don't think their hardships

are to be compared to our adventures & marches, sometimes we had no

water, but nothing is mentioned in the papers about us poor Tommies. I

don't know when our next move takes place, our Regt, or rather the 5th

Division, has been ordered round to the Cape, but I don't know whether

we shall be leaving, it will be a nice trip... This is a fearful place,

no water to wash with, we get our drinking water from Frere. I am afraid

I shall have to remain in this Corps for quite 6 months longer as I signed

for as long as my services were required by Her Majesty. All the Ladysmith

troops I hear are to go down to Highlands for a good feed... poor chaps,

they must want it badly after being so short of rations & having to

eat horses & mules... I tell you, I will be pleased when this war is

over. I am thoroughly tired of it all. Everybody in camp [is] suffering

from severe headaches and several have fever and dysentery; a few have

gone under. The Boers had a fearful time this last fight. The Lyddite played

'Old Harry' with them, the trenches were piled up with dead & several

women among them, one of the Boer prisoners stated that one woman was a

splendid shot & she was kept in the trenches to pick out the officers,

she was about 25 years of age... Mother seems to be in greater spirits

since the relief of Ladysmith, but I don't think the fighting is half over

& that I shall see a lot of fighting yet. Our Colonel Nash is not liked

at all by the men, he seems to order us about as if we were kaffirs or

coolies. I must close now hoping to hear soon.'

This letter is interesting for its references to the little-known Boer invasion of Zululand, which took place towards the end of February. A commando, entering from the east, captured first the Nqutu and then the Nkandhla magistracies. The Nkandhla Magistrate managed to flee before the Boers arrived, but the Nqutu Magistrate and neighbouring inhabitants (one of whom Hawkins names) were taken prisoner. Edie had good reason to fear the invasion since Eshowe was, for a time, vulnerable to an attack. The British responded by dispatching the newly-raised Colonial Scouts (the 'Scouts' referred to above), as well as a number of Bluejackets with naval guns to avert the threat.(3)

The engagement described at the end of the letter was the decisive battle of Pieter's Hill, which took place on 27 February. Here, after ten days of almost continuous fighting, the British broke through the Boer defences and opened the road to Ladysmith. The Boers indeed suffered heavily from artillery fire during this battle, particularly those manning the trenches on Hart's Hill, in the centre. It is also true that a number of women were fighting on their side at that time. One of them, just nineteen years old, was mortally wounded a few minutes after her husband was killed.(4)

The next letter, dated 'Colenso, 16-3-1900' was written to Hawkins'

mother:

'Dear Mama

We are now encamped in the above-mentioned place [Colenso]. Our camp is

within a couple of hundred yards from the railway station, so I suppose

they will put me on a lot of fatigue, loading wagons etc. One comfort which

we have is the river which is also close at hand, the water is of a khaki

colour. The trenches round here are beautifully built & I see any amount

of civilians going over them for relics. Our camp ground looks something

like a swamp and when it ruins I'm afraid we shall be floating about our

tents... I am glad to hear Henry & Percy have persuaded Scott not to

join the Light Horse as I don't think he would like to be ordered about

like a Kaffir & have a rough time, sometimes nothing but these hard

biscuits & wet through for twenty four hours at a stretch... I am pleased

we have left Chieveley, it was a miserable place & fellows were falling

sick daily with fever & dysentery, nearly two sent to the hospital

daily.. they are hard at work on the railway bridge here all through the

night, they have got the Boers' search-light working. I think the bridge

will be finished in a few days. I must close now, hoping you will write

soon again.'

Henry, Percy and Scott were probably Hawkins' brothers. The latter,

as references in later letters show, evidently changed his mind about not

enlisting and, by September, was fighting at his brother's side. On 10

April, Hawkins, still in Colenso, wrote to his sister once more. Only the

first page of this letter survives. Apart from the usual grousing, it concerns

his impending transfer to the Imperial Light Horse:

'Dear Edie,

l received your letter and hope you will not think it nasty of me for not

writing to you before now but I have been rather busy lately what with

parades and long route marches... Henry has tried to get me into the Carbiniers

but they don't want any more recruits so he has arranged a place for me

in the Imperial Light Horse. At present I am arranging a way to get my

transfer, which I think will be successful. I thank God the day I leave

this Regt, we are always on the move, not a minute's peace to ourselves.'

Hawkins joined the Imperial Light Horse on 13 April 1900, just in time to embark with the regiment for Cape Town from Durban four days later. During the course of the journey, it was learned that the ILH was to be sent to Kimberley to form part of a force being put together by General Hunter to relieve Mafeking. Colonel B T Mahon was eventually entrusted with the command of a flying column which on 4 May set out from Barkly West to link up with Colonel Plumer approaching from the north. The column, roughly 1150-strong, was comprised mainly of two locally-raised regiments, viz the ILH (814 officers and men) and the Kimberley Mounted Corps.(6) Other components included 100 men from General Barton's Fusilier Brigade, two pom-poms and four guns of 'M' Battery, RHA. On 16 May, Mahon and Plumer having successfully linked up, Mafeking was duly relieved after a siege lasting 217 days.

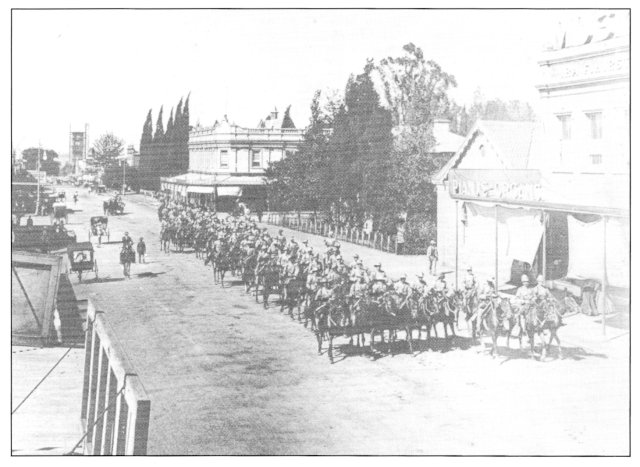

Troopers of the Imperial Light Horse

(Photo: By courtesy of MuseuMAfrica)

Hawkins was recovering from a severe leg wound sustained during the

relief when he wrote the following letter, dated 'Mafeking Hospital, 6-6-1900',

to his sister:

'Dear Edie

I suppose you know that I am wounded, the mater must have been in a fearful

state when she saw my name amongst the wounded. I had a fearful time of

it, and never expected to come through safe as the bullets were dropping

around me by hundreds. I lay on the field from half past four until 11

at night. I managed to get a chap to bandage my wound in the early part

of the fight, but it must have bled a basin-full, as there was a pool of

blood. When the bullet went through it burnt like a red-hot iron for a

time, it has only gone through a small bone in my calf and it is healing

up splendidly. I can manage to get around with a stick now, and will soon

be able to walk. We are expecting the train up from the south either tomorrow

or this evening, and I hear they are taking us all down to Kimberley &

the bad cases to Cape Town... We have got about 200 Boer prisoners here,

they do look such beasts, they are sending them also down to Cape Town.

This is a fearful dismal place - nothing whatever to buy, see or do and

everybody seems to be half dead. Lady Sarah Wilson is looking after us

here, we are in the school room which they have made into a convalescent

hospital... Food is scarce here, we are nearly starved & long sometimes

to have a good meat. My Regt is doing police duty, that is going out on

patrols and disarming rebels etc which is rather dangerous work at present.

The war is over now thank God, fancy old Kruger making a bolt with 10 000

Boers towards Delagoa Bay, he has also taken 2 millions in money with him.

I wonder what he thinks he is going to do. Lord Methuen is after him with

20 000 men and will soon put a stop to his forward move. We are attached

to Baden-Powell's Frontier Force at present... I must close now with my

love to Kit and yourself.'

The battle in which Hawkins was wounded took place near the Maritsani River on 13 May. It was the only attempt the Boers, preoccupied with trying to stem General Hunter's advance further east, were able to mount to halt the flying column. A commando under Commandant Liebenberg, numbering 600 with the majority being rebels from Griqualand (7), finally managed to place themselves in Mahon's path, occupying the heights at Koedoesrand, overlooking the main road through which his men would pass. Anticipating this, Mahon had decided to make a detour to the west, avoiding Koedoesrand altogether. It was a sensible decision, given the relatively small size of his own force. The column was advancing through bush country when, around 16.00, ILH scouts reported that a large number of Boers were marching parallel with the column with the evident intention of heading it off and attacking it.(8) So thick was the bush that Mahon's advance guard ran right into them and was temporarily driven back before the rest of the force rallied and set about clearing their assailants from the road.(9) The ensuing engagement lasted for perhaps three-quarters of an hour, but sporadic firing continued until long into the night, explaining why the wounded Hawkins was only brought in around 23.00.

The fight took the form of a large number of personal duels with firing taking place at close range. The ILH stood their ground well and the accurate fire of the artillery eventually beat off the burghers. Casualties on both sides amounted to about thirty killed and wounded.

Hawkins mentions Lady Sarah Wilson, Winston Churchill's paternal aunt and one of the most colourful characters of the Mafeking siege. Amongst other things, Lady Sarah was, for a time, held as a spy by the Boers and only released after Baden-Powell agreed to set free the Boer prisoner, Jeffrey Delport, himself suspected of spying. She went on to take charge of the auxiliary hospital in Mafeking.(10) Hawkins did not, in fact, go to Kimberley to recover fully from his wound, but to Pretoria. The following letter, dated 28 July, was written to his mother from there just before he rejoined his regiment:

'Dear Mama

As I have got a few minutes to spare I am writing to tell you that the

ILH are expected here tomorrow and that I will be able to join them.. We

have now got here a hundred and thirty two remounts in our lines, so you

can think how much work we have, there are about forty of us here. I shall

be awfully pleased to see Scott, he must be sick of the whole affair I

know I am. Sampson won't hear of disbanding the Corps, he intends seeing

the end now that he has started, everybody is thoroughly disgusted with

him. Our depot has been moved from Bloemfontein to here. There are a heap

of presents waiting to be distributed amongst us. Several fellows have

gone down to the hospital with dysentery. It has been fearfully cold here

lately during the evenings. Your balaclava cap has come in splendidly.

There is nothing going on here & we cannot get any news from the front.

I am feeling in splendid health and quite game for another fight. I may

not be able to write for a long time as I don't know where the Regt is

going and there may be no post that way so don't worry if you don't hear

again for some time. I must close now with much love to yourself and all.'

The Sampson referred to here is Colonel A Woolls-Sampson, OC of the ILH. He had fought with distinction at Elandslaagte and, in the process, had been severely wounded. By all accounts he seems to have been a brave and dedicated officer. However, as the above references to him show, he was unpopular with his men, and not without reason. For example, when the regiment entered Johannesburg, many of the men of the ILH (who, unlike Hawkins, came from the Rand) had requested a few hours leave so that they could investigate whether their property in the city was safe. Without communicating to his officers his reasons, if any, Sampson had refused - a decision which was particularly resented. The ILH had other grievances and, as Gibson notes, there was a great deal of dissatisfaction in the ranks around this time.(11) Not only the rank and file were concerned about Sampson's leadership. Kitchener went so far as to send a cable to London, asking that he be relieved.(12) It probably came as relief to all concerned when he became an Intelligence Officer.

In the early hours of 30 August, the ILH, as part of General French's

division, set out from Pretoria for Barberton. After seven days of constant

marching and patrolling, it reached Carolina in the afternoon of 6 September.

Here Hawkins took advantage of the rare respite to write once more to his

mother. By this stage, his brother had joined him:

'My dear Mama

We are now here, it's a miserable little place, only about 15 houses and

one can't get any eatables whatever. We have had rather a tiring march

so far, and a good many horses have knocked up and died during the march

so we have a few Tprs [troopers] marching. My horse has got a very bad

back and I shall also have to march until I can get another remount, it's

a Hungarian horse & mostly all our remounts are from that part, as

far as 1 can see they are useless animals. Scott's horse has also gone

wrong so he is dismounted and I think before long the whole Regt will be

the same. We are at present with French, his Division is here and I don't

know what we are after around this way. I don't like the appearance of

this part of the country at all, it's awfully barren & the veldt is

as dry as you could make it, there's not a blade of grass here and the

panorama gives one the blues. I often think what a fool I have been joining

the corps & wish for the end to come. We were after the Boers the day

before yesterday, they attacked 160 New Zealanders with two 15-pders and

wounded six & took six prisoners, they also fired on one of our goods

trains, when we went out there was no sign of them anywhere. I wonder when

it will all be over, the ILH are sick of it and long for the day when we

are disbanded... I am orderly for the day to the Quartermaster, a very

easy job, nothing to do so I am writing you in the spare time... the ILH

are gazetted as the 25th Hussars as an honour to us. I long for a good

feed again, it's an awful way of living this kind of life, the food is

fit for a dog in my estimation. We are all quite lousy again, oh it is

awful to feel them.'

In a post-script, Hawkins adds:

'We are leaving here tomorrow I think, whereto I could not say, this

marching is fearfully monotonous & not knowing where one is going.

What is the opinion now as to when it will be over? I hope to God soon.

Sampson is going to see it through to the end so they say We would have

been disbanded if it wasn't for him.'

Apart from having another dig at Woolls-Sampson, the letter notes the difficulties the ILH experienced with their remounts, believed to have come from Hungary. Though these were good-looking animals, they either did not acclimatise or possessed no stamina, and Lieutenant Blake eventually had to be sent around to the well-known horse breeding farms in the district to obtain replacements.(13) There is also a reference to the previous day's attack by Commandant Dirksen's Boksburg Commando on a small outpost of Canadians (incorrectly identified by Hawkins as New Zealanders) at Wonderfontein. Dirksen broke off the attack when he learnt of the ILH's approach and was well clear by the time they arrived.

On 16 September, having encountered minimal resistance, the column

finally reached Barberton. Here Trooper Hawkins, in considerably better

spirits for reasons that will become apparent, wrote the last of his letters,

at least of those that have survived:

'Dear Mama

I suppose you are all rather anxious about Scott and self. Well, we have

had several little skirmishes with the Boers and on both occasions were

under a 15-pounder gun fire which was rather uncomfortable when the shells

came within two yards of us, but luckily as per usual they didn't burst

so did no damage. We got the Boers on the chase both times, it was grand

sport popping at them, they left several wagons laden with flour and sugar

which came in splendidly for us all. We have also got about a thousand

sheep and a few hundred cattle. At present we are getting plenty of fresh

meat besides rations. I made three small loaves of bread today, they turned

out splendidly, better than I thought they would. lt's fearfully warm here,

something like the Durban climate. I have not been into Barberton yet,

we are about two miles out of town and the fellows who have been in say

the place is in a fearful state. We can buy anything we want at a liberal

price such as jam and tin stuff. The Boers cleared when they saw the Khakis

coming and six of our men took the town. I can't make out why they didn't

make a stand here, it's a brutal country for fighting in, it's nothing

but huge mountains covered with boulders. I think we shall soon be disbanded

now as it's really practically all over, the Boers seem to have lost all

heart in fighting which is quite time. Scott is on grazing guard, it's

my turn tomorrow... I could have got some of those blank coins which Kruger

was using but hadn't the money to purchase them, it's beastly hard lines

I think, they really would have been a great curio. Several fellows have

had rather beastly spills off horseback, some have broken their arms and

fingers. I must close now, hoping soon to be back with you all and have

a good chat.'

The skirmishes described at the beginning of the letter took place between 12 and 14 September 1900. On 12 Sept ember, the Boers, to cover their withdrawal, brought a 15-pounder and a pom-pom into action but without success, causing neither casualties nor delay. This is hardly surprising since, as Hawkins remarks, their shells invariably failed to burst. Seven wagons full of supplies were captured by the ILH after the British brought their artillery into the picture. Another wagon was taken on 13 September, as well as 100 horses and 900 sheep. For a change, therefore, the perpetually hungry troopers had more than enough to eat, and this doubtlessly explains the relatively upbeat tone of Hawkins' letter. That same day, French, at the head of the 1st Cavalry, outflanked Smuts and captured Barberton without a shot being fired. These were indeed heady days for the British Army in South Africa. Enemy resistance was collapsing on all fronts and the war was becoming little more than a mop-up operation. Hawkins can be forgiven, therefore, for writing that it was practically all over. Little did he realise that the war, whose end he had longed for ever since joining up, would run for almost another two years. Apparently well beaten, the Boers were unexpectedly about to launch a new phase in the conflict, effectively introducing guerrilla tactics to counter their opponents' numerical superiority. What part, if any, Hawkins played in this phase is uncertain as we have no further letters of his (at least not in MuseuMAfricA). However, since the ILH Memorial to their dead in the South African War does not include his name, we can at least assume that he survived it and returned to his family, perhaps even convincing them and himself as the years went by, that it was actually all a fine old adventure in retrospect.

References

1. The author wishes to thank Colonel Gibson of the Light Horse Regimental

Association for this and other pieces of information regarding Hawkins.

Col Gibson, incidently, is the nephew of the Gibson mentioned below.

2. Amery, L S (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa (London,

1906), Vol III p 328.

3. Scott, C H, The Boer invasion of Natal, being an account of Natal's

share of the Boer War of 1899-1900 as viewed by a Natal Colonist (London,

1900), pp 219-20.

4. Holt, E, The Boer War (London, 1958).

5. Gibson, G F, The History of the Imperial Light Horse in the South African

War, 1899-1902 (Johannesburg, 1937), p 166.

6. Pakenham, T, The Boer War (London/Johannesburg, 1979), p 416.

7. These are the rebels to whom Hawkins refers as being disarmed.

8. Gibson, History of the ILH, pp 171-2.

9. Maurice, F, History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902 (London, 1908),

Vol III, p 182.

10. Midgeley, J F, Petticoat in Mafeking: The Siege letters of Ada Cook

(J F Midgeley, 1974), p 145.

11. Gibson, History of the ILH, p195.

12. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 540.

13. Gibson, History of the ILH, p 219.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org