The South African

The South African

by W P Schutz

Nearly 80 years ago, on 24 August 1916, the writer's grandfather, Maj W A Bloomfield (then a captain), won the VC (Victoria Cross) at a place called Mlali in German East Africa. He was the only man in a South African unit to win the award in that arduous campaign. In later years, he was not forthcoming on his deeds on that day and, as youth is heedless with history, the writer did not know much more about them than what appeared in the official citation. Bloomfield died at the age of 81 at his home in Ermelo in 1954.

As the years passed, the writer's wish to visit the scene of his grandfather's act of great bravery increased, but the prospects of a South African tramping around in the Tanzanian bush in search of a colonial battlefield became poorer and poorer. However, in 1994, the approach of long leave at a time when South Africa had returned to the world offered an opportunity.

Locating the general area from printed sources was not a difficult task. The two day action at Mlali took place in the course of one of the many unsuccessful attempts to corner the elusive German commander, von Lettow-Vorbeck. In earlier months, the 'British' forces, under the overall command of Gen J C Smuts, had driven the Germans from the Kilimanjaro-Meru area and had captured the port of Tanga and the northern railway which ran to Moshi at the foot of Kilimanjaro. Maj-Gen J L van Deventer had been given command of a sweep to the west and, in due course, he had cut the recently completed central railway line that ran from Dar es Salaam to Lake Tanganyika. Gen Smuts retained direct command of the eastern advance, initially down the Pangani River valley, driving von Lettow-Vorbeck southwards, his retreat to the west having been blocked by van Deventer's successful advance.

As Smuts approached the central line at Morogoro, 129 miles (207 km) inland from Dar es Salaam, his aim, according to his despatch, was 'to bottle the enemy up in Morogoro' by seizing Mlali, which lay on the road to the west of the Uluguru mountain range, some fifteen miles (24 km) away, whilst simultaneously blocking the road to the east of the range.(1)

The Ulugurus, which run from north to south, are high, rugged and long. Von Lettow-Vorbeck had a different perception of being caught in such a difficult position:(2) 'The enemy expected us to stand and fight a decisive engagement near Morogoro, on the northern slopes of the Uluguru mountains. To me, this idea was never altogether intelligible. Being so very much the weaker party, it was surely madness to await at this place the junction of the hostile columns [van Deventer and Smuts], of which each one individually was already superior to us in numbers, and then to fight with our back to the steep and rocky mountains...

In addition, Smuts' afore-quoted despatch records: 'I was not then aware that a track went due south from Morogoro through the mountains to Kissaki and that the capture of the flanks of the mountains would not achieve the end in view'. This was knowledge gained after the event.

The task of cutting off the western escape route at Mlali was given to Brig-Gen B G L Enslin, in command of the 2nd South African Mounted Brigade. Captain Bloomfield was a member of the scout corps attached to the brigade. Von Lettow-Vorbeck's observers on the mountains watched the dust clouds approaching. Mlali from the north-west and he decided to attack this isolated detachment with his full force.(3)

Enslin neared his destination late on 23 August 1916 with only some 1 000 men and four guns and, on the morning of 24 August, occupied Kisagale Hill, which commanded the Morogoro-Mahalaka-Kissaki main road and overlooked the Mlali river.4 Meanwhile, on the evening of 23 August, von Lettow-Vorbeck had ordered Capt Otto, at Morogoro, to march to Mlali during the night with three companies, of roughly 200 men each.(5) Apart from the great advantage of observation from high ground, the Germans made use of telephones and bicycles and were very amply provided with porters, rendering them very mobile. Captain Otto arrived early on the morning of 24 August, just as the 'English' (Enslin under the command of Maj-Gen Brits, who was in turn under the command of Gen Smuts) had taken the depot at Mlali.(6)

The depot contained a dump of some 200 rounds of 4,1 inch (105 mm) gun ammunition, salvaged from the cruiser Konigsberg, 300 other shells, a large quantity of supplies, and many cattle.(7) Von Lettow-Vorbeck wrote that there were 600 tons of food and military stores at the depot.(8)

According to Hordern, the South Africans were fired on from a farm east of the river across which the Germans had retreated. In order to envelop this post, a part of the brigade, headed by the 5th Horse, crossed the river some two miles (3,2 km) upstream, but the advanced troops were checked 'on reaching the edge of a small tributary valley, by heavy fire from the higher ground beyond it'. 'Soon afterwards,' wrote Hordern, 'two enemy guns came into action behind the defended farm, and on the arrival of the German reinforcements and the development of a threat to his extended right flank, Enslin recalled the 5th Horse.. . '(9) It was in the course of this withdrawal, in which Bloomfield and his men had been given up as lost, that he is believed to have earned his VC.

When von Lettow-Vorbeck arrived on the scene in the morning, he found the fight to be in full swing and ordered up most of his troops, who were still at Morogoro. (These were the reinforcements mentioned above by Hordern). The many steep hills impeded offensive action and, by the afternoon, the outcome of the clash remained undecided, although the South Africans had been driven back at several points and had been seen to suffer considerably.(10)

Enslin withdrew to Kisagale Hill to await reinforcements. Although the Germans advanced two light guns on his right flank on 25 August 1916, they later withdrew into the hills south-eastwards, towards Mgeta Mission.(11)Before retreating with the augmented force of ten companies, however, they were forced to blow up two quick-firing naval guns of 3,5 inch calibre (88 mm), as the wagon road did not continue into the hills and they were reduced to using a footpath.(12) Later, they retreated through the mountains in the direction of Kissaki, despite being pursued, and the campaign swept on southwards.

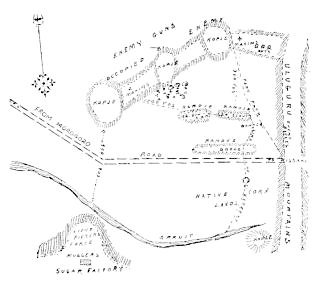

During his visit to Tanzania, the writer hoped to locate the battlefield where his grandfather had earned his VC. However, even with the aid of the rough sketch map, with a scale of 1 inch: 3 393 yards (1 cm: 1 221 metres), which appears in Hordern's book and gives some idea of the area, the prospects of pinpointing the exact location of the action did not appear to be good. Maps 15 and 18 in Collyer's book, The South Africans with General Smuts, also provided some assistance.

The writer then had the good fortune of speaking to Mrs Barbara Worby, senior librarian at the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg. In addition to referring him to the books by Hordern and Lucas, she reminded him of some letters, dated 1917, of which the museum has copies and his family the carbon originals. One, from Trooper E W Hurly, referred to an article which appeared in The Sunday Times on 18 March 1917. A copy of the newspaper was soon located in the Johannesburg Public Library. The article included an account of the action, provided, with characteristic reluctance at first, by Bloomfield himself. Illustrating the article was a rough sketch map, which was clearly prepared under his directions. It was the treasure for which the writer had been looking.

Thus prepared, on 13 February 1995, the writer, his wife Moyra and their driver and guide, Said from Dar es Salaam, turned off the main Morogoro/Iringa road onto the unmarked road to Mgeta which runs through Mlali. After having passed through the latter, they eventually reached a spot which gave the writer a sensation of déjà vu, which he suspected was really to be accounted for by the sudden appearance of a three-knolled hill, a main feature in the Sunday Times sketch map. Nevertheless, he was confused by where the roads might once have been, and worse, he had forgotten to bring a compass, which would have been more useful than binoculars at 10:00 on an overcast morning. Fortunately, he decided to press on for the time being. Almost at once, they were amid steep hills on the way to Mgeta. Even today, caterpillar traction would be required to pull a gun along that road. After a time, the two-wheel drive vehicle could go no further and, with some effort, they were able to turn it around.

While they were admiring the beautiful scenery of green hills and valleys, a very old man came past, heading in the direction whence they had come, towards Mlali and, as he said when asked, towards Morogoro some fifteen to twenty miles (24-32 km) away. Daemeon, as they learned his name to be, was clearly very old, with rheumy eyes and a few isolated teeth. He had come walking along at a steady pace, if not with an extended stride, a staff in his right hand, a small sack over his shoulder and a light panga under his left shoulder. As the large long-legged ants ran over his bare feet without him taking any notice, Said, who had been talking to him in Swahili, remarked in admiration that here was still one of the old African people who just walked and walked until they reached their destination.

At this point, the writer took a long shot through Said. Did the old man remember the war? 'Which war?' he replied, 'Between the Germans and the Dutch?' This, the writer felt, was the touch of absolute authenticity - the Germans had fought against Enslin, Brits, Smuts and van Deventer (also, no doubt, Hannyngton, Sheppard and Hoskins, but they had been involved in cutting off the Germans on the eastern side of the Ulugurus - far way). How old was he at the time? 'About fifteen' was the reply. Could he show them where the war had taken place? 'Yes, but we would have to go back towards Mlali.' They offered him a lift and, as they turned the corner to arrive back at the 'place of déjà vu', Daemeon pointed to his left towards a low ridge across the flood plain and said, 'That is where it started', speaking with the imperious authority of great age.

Looking around, further details from the Sunday Times sketch fell into place. From the road, looking roughly north-west, the three-knolled hill remained a prominent and distinct feature. The road runs below this hill on the rim of a broad, flat flood plain, under cultivation now as it assuredly was 80 years ago. On its far side is a spruit and, immediately behind it, a low ridge, with a range of taller hills some distance beyond it. As one looks up towards the crest of the three-knolled hill, there are some low ridges in the middle distance and, immediately next to the road, another. To the right stands a high conical kopje - again a feature that would imprint itself on the mind.

They took Daemeon some distance further on his way. When they dropped him off, after resuming his goods, he said 'Asante, asante' ('Thank you, thank you') for the few dollars he had been given, turned and continued on his steady way to Morogoro. Another day in the tens of thousands.

The official citation of 30 December 1916, for

Bloomfield's VC, is to the point militarily, if geographically

austere:(13)

'Finding that, after being heavily attacked in an

advanced and isolated position, the enemy were working

round his flanks, Captain Bloomfield evacuated his

wounded and subsequently withdrew his command to a

new position, he himself being among the last to retire.'

'On arrival at the new position, he found that one of the wounded - No 2475 Corporal D M P Bowker - had been left behind. Owing to very heavy fire he experienced difficulties in having the wounded Corporal brought in. Rescue meant passing over some 400 yards [365 metres] of open ground, swept by heavy fire, in full view of the enemy. This task Captain Bloomfield determined to face himself, and unmindful of personal danger, he succeeded in reaching Corporal Bowker and carrying him back, subjected throughout the double journey to heavy machine gun and rifle fire.'

'This act showed the highest degree of valour and endurance.'

Inspections in loco, the writer has found in the course of legal practice, are often rewarding. Things simply do not look the way you had imagined them and so it was in this case. The lowering menace of the high three-knolled hill with its 'two Maxims' and 'four Maxims', and the 'enemy guns' behind, and the enveloping 'enemy rifles' on the right flank became apparent at once. Much of the ground that had to be twice covered along the 'line of retreat' was in full view of the enemy positions.

The 1917 Sunday Times article and the correspondence to which it led helped to fill out the rigorous official citation. It had been preceded by a letter written by the slowly convalescing Bowker to the Staff Officer for War Recruiting on 24 January 1917, presumably upon hearing of the award of the VC to Bloomfield, which had been published 26 days earlier in London.

Bloomfield was still in East Africa - 'that dreadful country' as Bowker's mother had already written to Mrs Bloomfield in gratitude for her husband having rescued her son - and a letter by Bloomfield, written on 7 June 1917 in South Africa, indicates that, immediately after the action at Mlali on 24 August, he had been sent off on a mission to Kissaki with Sgt Theron. Apart from Theron, Bloomfield had not seen his men again in the nine months intervening. After expressing his gratification at the award of the VC to Bloomfield, Bowker went on to mention, should it not be known, that there had been another hero on the day, Trooper Hurly.

When Bloomfield had initially called for two volunteers to carry the severely wounded Bowker back, Hurly had volunteered at once. After they had covered some distance, the second man, a corporal, who will simply be referred to as 'O', left, as Bowker tactfully stated, 'in search of assistance, but was unable to return.' The wounded Bowker and Hurly were then joined by Trooper Trickett and they went a little further, until they 'were suddenly fired upon and were obliged to take cover.' It was there that Bloomfield found them on his return journey. Hurly stayed with Bowker throughout 'and behaved I consider splendidly', he said. Trickett, who was much weakened by malaria and fatigue, also remained with them, despite suggestions that he should save himself. From later correspondence, it becomes clear that it was the desertion of 'O', one of the pair chosen as capable of carrying Bowker back, at a stage when the rest of the men later came by in retreat, which occasioned the need for the subsequent rescue of Bowker and the peril of Hurly and Trickett, who had been left behind.

Sketch map from the Sunday Times of 18 March 1917, describing the events at Mlali on 24 August 1916, when Major Bloomfield earned his Victoria Cross.

In reaction to the Sunday Times article of eleven days

previously, Trooper Hurly wrote to Bloomfield, who was

by then back in South Africa between campaigns, on

29 March 1917. Although Hurly clearly respected

Bloomfield and approved his award, he took exception to

the suggestion in the report that he, as well as 'O', had

abandoned Bowker. 'It is quite possible,' he wrote, 'that

the reporter made a mistake and that the error has not yet

come to your notice.' His complaint against the

inaccuracy of the report was justified and his resentment

at the injustice natural and Bloomfield's reply confirmed

that there had indeed been a mistake. Later, when

Bloomfield, in his turn, wrote to the Staff Officer for

War Recruiting on 7 June 1917 in response to a request

to comment upon Bowker's letter of 24 January, he said,

'I fully agree with Cpl Bowker that Hurley [sic] behaved

splendidly that day.' Immediately after the action,

Bloomfield had verbally reported on the conduct of various of

his men, including Hurly, to his commanding officer. He

had then been sent off on the mission to Kissaki without

them. Not long afterwards, the 2nd Mounted Brigade

was disbanded, owing to a lack of horses and men, and

Bloomfield's report to his OC seems to have died there.

Whatever its defects, the newspaper report remains the

earliest dated account, which the writer was able to find,

which referred to the action of the 42 men of the advance

formation under Bloomfield's command. The report

proceeds:

'The forces under Lieut Peters, on occupying Muller's

Sugar Factory [depicted on the sketch], found that it was

used as an ammunition store by the enemy, who, as it

was subsequently ascertained, was some 800 strong

[before the arrival of the reinforcements]. It was

anticipated that the enemy was aiming at reaching the

road to Kissaki, and it was with the intention of

frustrating this effort, that Major [as he had become]

Bloomfield was instructed to occupy the randjes lying

between the kopjes occupied by the enemy and the road.

[Although both the map and the text refer to the road to

Kissaki, the writer is convinced that this reference was

not to the main road to Kissaki, which was already

overrun, but to the road, or, as it became further on, the

path to Mgeta by which the Germans ultimately retreated

to Kissaki].'

Major W A Bloomfield, VC

(Photo: SA National Museum of Military History)

'To attain this object, it was necessary to make an easterly detour along the spruit, and across native cornfields, before crossing the road and taking up the positions on the randjes, which proved to be only some 600 and 1 000 yards (550 and 900 m) distant from the kopjes occupied by the enemy with six machine guns. After one man had been killed, five wounded, and the ammunition practically exhausted, Major Bloomfield gave orders for his men to retire, at the same time giving instructions to Cpl "O" and "a private" to take Cpl Bowker, who was wounded, along with them to a place of safety.'

[Although the transition of casualties and retreat in this account is abrupt, the action had lasted some five and a half hours, the German reinforcements were arriving and the envelopment of the small advance force, which was running out of ammunition, had begun.]

'On arriving at the tree in the native cornfields [depicted in the sketch], Major Bloomfield found that "O" and "the private" [this was the cause of Trooper Hurly's complaint] had left Bowker behind and, on asking the reason was told that on account of the hot fire of the enemy it was absolutely impossible to bring the wounded corporal with them more than a distance of about thirty yards [27 metres].'

[Bloomfield's own words in his letter of 7 June 1917 are more graphic: 'I saw the corporal whom I had sent in charge of Bowker and asked him why he had not brought the wounded man out. He replied he could not have brought him out even if he had been his own brother, the fire was too hot.'] The newspaper report continued: 'Major Bloomfield asked them to go back and fetch the wounded man, but was told a second time that such a course was impossible. Two other well-built soldiers were also asked to go and fetch Corporal Bowker, but they made the same excuse. Major Bloomfield ... thereupon set off himself alone to rescue the wounded corporal. By this time the enemy had worked round to the Uluguru Mountains [depicted in the sketch, but probably only the foothills] and not only had Major Bloomfield to run the risk of their rifle fire, but also of the six machine guns posted on the kopjes some 600 and 1 000 yards [550 and 900 metres] away from where the wounded man had been left. Bullets fell thickly all around him, but, by creeping on hands and knees where the grass was 2 ft [60 cm] high, and racing at full speed through exposed positions he managed to reach the wounded man without any mishap.'

[In his letter of 7 June 1917, Bloomfield's version of

the story was as follows: 'On returning to look for the

men under a hot rifle and maxim fire at 400 yards (365 m)

range on both my flanks, and reached (sic) a point about

300 yards (274 metres) from my former position, which

the enemy had now occupied, I saw Hurley (sic) sitting

in a slight wash out covered with grass about 30 inches

(75 cm) high and on approaching nearer saw Trickett

down the sluit. I asked "Where is Bowker?" Hurley

(sic) replied "Here, I am looking after him." Hurley (sic)

is not a strong man and could not possibly carry Bowker,

not even with Trickett's aid who was very weak from

malaria at the time.'] The newspaper report continues the

story:

'[Bloomfield] took Corporal Bowker on his back, and

sent the two other unwounded soldiers on in front [to

avoid making a big mark, according to Bloomfield's

letter]. Corporal Bowker asked Major Bloomfield not to

trouble with him but to leave him to his fate, as it was

hopeless to expect to carry him in safety through enemy

fire. Nothing daunted, however, Major Bloomfield

picked up the wounded corporal and carried him on his

back as quickly as possible when passing through exposed

situations. Where grass was present he crept on his

hands and knees, still carrying the wounded man on his

back, with enemy bullets flying all around him. On

reaching the slight rise on which several native huts are

built [depicted in the sketch], Major Bloomfield found it

necessary to rest for a short spell, [Bloomfield was a tall,

lean man of about 150 lbs (68 kg), whereas Bowker

weighed some 180 or 190 lbs (82-6 kg)] after which he

set off for the tree on the other side of the Kissaki road,

where he arrived safely with Corporal Bowker, after

carrying him through country swept by the enemy's fire

of machine guns and rifles for a distance of about 1 400

yards [1 280 metres]. [This may be an error for 400 yds

(365 m)]. Four times during this perilous journey did

Cpl Bowker ask Major Bloomfield to leave him behind

and save himself, but no heed was paid to these

entreaties.

That really ends the account of the deed for which the VC was awarded, but the perils of the day were not yet over. In his letter of 7 June, Bloomfield continued:

'On arriving at the horses and safety the enemy continued to advance and occupied a position which commanded mine. I ordered the wounded and horses to be moved about a mile further back to a spruit. The enemy still advancing crossed the spruit where I tried to make a further stand, the only ammunition which we now had was a few rounds carried by the men who had been holding the horses. I endeavoured to keep the enemy off with these few men while the wounded were being evacuated and gave orders to the other men to make a run for it on to our main body to avoid capture. By some misunderstanding Bowker was left (a second time), only Hurley [sic] being with him. I sent Hurley [sic] for a horse to get Cpl Bowker out as I was too tired to carry him myself. Hurley [sic] brought the horse under heavy fire. We were exposed to a flank fire all the time. Whilst we were getting Bowker on the horse, Hurley [sic] was wounded, leaving me with two wounded men. Sergt ('Skewie') Theron at a distance seeing my plight came to my assistance at considerable risk with a horse for the other man ... Hurley's [sic] action in the latter phases of the engagement cannot be too highly commended, he was perfectly fearless until wounded.'

Contrary to what is said in the press report, the letter

also states that, when Bloomfield set out on his return

journey to look for Bowker and the other two, he was not

alone:

'Whilst reporting on this subject, I would like to draw

attention to Sergt Theron's behaviour during this action.

When I decided to return to look for the missing men, I

asked if anybody would volunteer to return with me.

Sergt Theron did so: we started off under heavy fire. I

had proceeded about 700 yards [640 metres], Theron

following me up, the enemy here concentrated their

maxims on us. He said it is impossible to go further. I

told him to wait there and watch. I then went on alone.

It was about some 700 yards further on [these distances

could not be reconciled with the sketch map] to where I

found Bowker and the other two men. Theron it appears

followed me up at some distance behind, as I met him

about 150 yds [138 metres] back on my return journey

and gave him my rifle and helmet to carry.

'This together with his action already mentioned in the former part of this letter was worthy of notice.'

Major Bloomfield added that he had given the names

and facts in his verbal report to his OC some nine months

before. In repeating them, he said:

'I have given these sketchy details as proof that these

men went thro' a stiff and trying time and also for the

reason that it is apparent these men were not given their

due, and not even mentioned.'

Bowker survived the war. Had he not been rescued, his fate may have been a particularly unhappy one. Hurly's letter remarks that, had he abandoned Bowker as 'O' had done, the wounded man would have been left to his fate 'no one knows what'. There is also an undertone in Bloomfield's letter when he writes: 'I am convinced that had I been five minutes later in returning for the three men all would have been captured by an exasperated enemy, who were very angry to find so small a force (42 of all ranks) had held them up and destroyed a large quantity of munitions.'

The other VC of the campaign was awarded posthumously to Lt W Dartnell of the 25th Royal Fusiliers for his bravery at Maktau on 3 September 1915. In the knowledge that the askaris murdered the wounded, Dartnell had insisted on remaining behind with some severely wounded men who had been abandoned. In doing so, he had hoped to save their lives. Also wounded, he would have been carried away had he not refused. As a result, he was murdered with the others.(14) His conduct well illustrates the conspicuous bravery which earned him the Victoria Cross. In a similar manner, Bloomfield earned his VC by going back into a hotbed of fire which other brave men could not face.(15) To this should be added Uys's dedication to his book, For Valour: 'To the memory of all those South Africans who deserved the Victoria Cross for their valour, but who in most cases went unrecognised.' While the writer does not suggest that they had earned the VC, the cards that chance dealt to the unrecognised Hurly and Theron are illustrative of this.

After all these years, one looks back to the Great War with dismay and awe. The East African campaign was often a matter of spirit sustaining the body; spirit and hope that victory was within reach. Many of the troops shared Smuts' expectations of victory as they approached the Ulugurus. On 20 August 1916, four days before the action at Mlali, Bloomfield had written home: 'The enemy have lost very heavily, every time we have met he has been punished severely, their spirit is being broken badly and do not think they will fight so well again except perhaps in the neighbourhood of Morogoro where they will make their final try.' The sequel is history. However, not everyone shared Gen Smuts' sanguine expectations. His Chief of Intelligence, Col R Meinertzhagen, who liked and respected him, but disapproved of his strategy and tactics, wrote at this time:(16) 'Von Lettow is slippery and is not going to be caught by manoeuvre. He knows the country better than we do, his troops understand the last word in bush warfare and can live in the country.'

Who really won the campaign remains controversial. It is true that, by the end of the year, the Germans had been driven out of most of their colony, allowing a victory to be declared in 1916. However, von Lettow-Vorbeck's aim was not victory, but rather to draw onto himself and to hold as many Allied troops in East Africa as possible. In this he succeeded outstandingly and he remained undefeated when the Armistice was declared on the other fronts.

References

1. J A Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts in German East

Africa, 1916, p 188, quoting Smuts' despatch.

2. P von Lettow-Vorbeck, My Reminiscences of East Africa, p 149.

3. Von Lettow-Vorbeck, My Reminiscences of East Africa, p 150.

4. Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 199; War Diary of

the 2nd SA Mounted Brigade, 24 August 1916, Public Records Office,

London, W109515347; J H V Crowe, General Smuts' Campaign in East Africa, pp 197-8.

5. Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 199; War Diary of

the 2nd SA Mounted Brigade, 24 August 1916, Public Records Office, London, W1095/5347;

Crowe, General Smuts' Campaign in East Africa, pp 197-8.

6. Von Lettow-Vorbeck, My Reminiscences in East Africa, p 150.

7. War Diary of the 2nd SA Mounted Brigade, 24 August 1916, Public

Records Office, London, W109515347.

8. Von Lettow-Vorbeck, My Reminiscences in East Africa, p 151.

9. C Hordern, History of the Great War - Military Operations East

Africa, Vol 1, August 1914-September 1916, p 356.

10. Von Lettow-Vorbeck, My Reminiscences in East Africa, p 151.

11. Hordern, History of the Great War - Military Operations East Africa,

Vol 1, August 1914 - September 1916, p 356.

12. War Diary of the 2nd SA Mounted Brigade, 24-25 August 1916,

Public Records Office, London, W/09515347.

13. London Gazette, 30 December 1916.

14. Ian S Uys, For Valour: The history of Southern Africa's

Victoria Cross heroes, pp 205-8.

15. Ambrose Brown, They fought for King and Kaiser: South Africans in

German East Africa, 1916, p 273.

16. R Meinertzhagen, Army Diary, 1899-1926, p 195.

Bibliography

Collyer, J J, The South Africans with General Smuts in

German East Africa, 1916 (Government Printer, 1939).

Crowe, J H V, General Smuts' campaign in East Africa

(John Murray, London, 1918).

Hancock, W K, Smuts: Volume I:- The sanguine years

(Cambridge University Press, 1962).

Hordern, C, History of the Great War: Military

operations East Africa, Aug 1914 - Sept 1916 (H M

Stationery Office, 1941).

Von Lettow-Vorbeck, P, My reminiscences of East Africa

(Hurst & Blackett, London, 2nd edition).

The London Gazette, 30 December 1916.

Lucas, C, The Empire at War, Volume 4 (Humphrey

Milford Oxford University Press).

Meinertzhagen, R, Army Diary, 1899-1926.

Uys, I S, For Valour: The history of Southern Africa's

Victoria Cross heroes (Galvin and Sales Pty Ltd,

Cape Town, 1973).

War Diary of the Second SA Mounted Brigade (Public

Records Office, London, W/095/5347).

Letters:

Maj Bloomfield to Mrs MM Bloomfield, 20 August 1916.

Mrs BS Bowker to Mrs MM Bloomfield, 7 January 1917.

D M P Bowker to Staff Officer for War Recruiting, 24 January 1917.

E W Hurly to Maj Bloomfield, 29 March 1917.

Asst Staff Officer for War Recruiting to Maj Bloomfield, 20 April 1917.

E W Hurly to Maj Bloomfield, 23 April 1917.

Maj Bloomfield to Capt Scott A SO for War Recruiting.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page