The South African

The South African

by Mannie Centner

This is a personal account of the experiences of a member of the 1st South African Light Tank Company of the South African Tank Corps, which served in the 1st South African Division, South Africa's expeditionary force in East Africa during the Second World War, as recalled by the writer, ex-Sergeant Mannie Centner: At the time of South Africa's declaration of war against Germany in September 1939, the South African defence force did not possess any armoured vehicles or tanks. At the training camp at Sonderwater in May 1940, some of the new recruits, mostly from Cape Town, were asked to volunteer for service in 'Tanks in the North'. At the age of 32, the writer was older than most of the other volunteers, who were mostly is to 20 years old. The volunteers were immediately despatched to Voortrekkerhoogte, Pretoria. On 16 July 1940, they were sent to Durban, where they boarded a small ship and sailed for Mombasa on 24 July.

From Mombasa, they travelled via Nairobi to a place called Gil-Gil. Within a few days, twelve 'light tanks' arrived. These could be described as 'tankettes', built on tracked Bren Gun Carriers and propelled by Rolls-Royce engines. The total armament of the vehicle was a single Vickers machine gun. At the same time, twelve Ford 10-ton trucks, converted into 'portes' to transport the tanks, also arrived.

After driving the tanks up the ramps onto the portes, the light tank company headed due north, past Mount Kenya and on to Nanyuki, the last inhabited village which lay directly on the Equator. At that point, the road became rocky and rough, causing the tanks to sway on top of the trucks. They pushed on for hundreds of miles into thornbush country and, turning off to the left, arrived at their destination - an old waterhole called 'Arbo Wells'. There they stayed for some months, expecting the Italian attack at any time.

On 17 December 1940, the light tank company attacked a small Italian fort, El Wak, and scored the first Allied victory of the Second World War (after a long series of defeats at Dunkirk, Greece, Crete, etc). During the same month, the first units of the 1st South African Division arrived in East Africa.

The 'push' began in February 1941, with the Italians retreating as they were chased through Kismayu, Mogadishu, Jigjiga, Harrar and on to Addis Ababa, which the South Africans reached in April. From there, the 1st South African Division was sent to North Africa where they were to come up against the German commander, General Erwin Rommel.

Meanwhile, the light tank company remained in East Africa, pushing westwards with the assistance of the Indian Mounted Artillery - small cannons mounted on the backs of mules. They cleaned up the rest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) of most of its 250 000 Italian troops. To the best of the writer's knowledge, no mention of the light tank company was made in any newspaper, magazine or any of the numerous books on the Second World War.

After the Allied victory in East Africa and later in North Africa, some research was done at the Italian Intelligence Headquarters in Addis Ababa. There it was discovered that the Italian General Staff had considered seizing Nairobi in Kenya. Such a plan would merely have entailed driving a small force into Kenya to brush aside the few hundred men of the King's African Rifles stationed there. However, reports from Somali spies, sent across the border to northern Kenya, mentioned the presence of 'large armoured forces of British tanks stationed near Arbo Wells'. The plan to seize Nairobi was then abandoned.

A driver once brought a small lion cub, picked up in the bush, into the camp, and it became the company mascot. At first, it was very cuddly and playful, but as it grew bigger, it became quite troublesome and mischievous. By the time the 'push' began in January 1941, it had become quite a problem and a nuisance. When the company entered Addis Ababa, they had the brilliant idea of forming a small delegation and making an appointment with the Emperor ('the Lion of Juda'), HRH Haile Selassi having returned to his palace. There they made a formal presentation to him on behalf of 'the Government and the people of the Union of South Africa'. It was a great success - in one stroke they were able to get rid of the lion and improve the international relations between the two countries.

Several attempts to procure venison were unsuccessful. The only buck encountered (and shot) were two large eland, but the meat was found to be riddled with 'measles' (parasites) and the carcases were condemned and discarded. Instead of venison, they had to open more bully-beef.

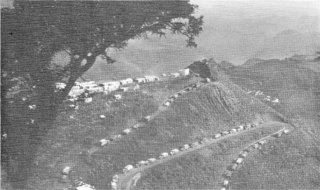

A convoy of trucks makes its way along

an Abyssinian mountain pass.

Several men in a number of tents had secretly prepared what came to be known as 'time bombs'. Earlier, a truck from Nairobi had delivered bags of small aluminium boxes, inscribed 'Merry Xmas', from Ouma Issie Smuts, the good wife of South Africa's Prime Minister Smuts. Every man was presented with a tin, which contained sweets, crystalized fruits and other treats. Someone had had an ingenious idea and a large quantity of sweets were thrown into five gallon petrol tins. Some yeast was added (by compliments of the cook), as well as any other available fruit, such as prickly pears, and the tins were then buried inside some of the tents to ferment, mature and hopefully produce a potent brew for the Christmas celebrations.

Unfortunately, instead of alcoholic refreshments, the concoction produced powerful gases, causing explosions which blew up the tins and soil all over the interior of the tents. At Christmas, the men had to be content with 'rum issue', a vile South African brandy which, if the story is to be believed, could dissolve the enamel of the army issue mugs!

Seeing himself as an instant millionaire, the writer grabbed as many notes as he could, stuffing them into a canvas bag which he had found and making a dash for his vehicle, a Ford 3-tonner. He dared not linger a minute longer as the company was on the heels of a fleeing Italian Army and looting was just 'not on'. At nightfall, they stopped for a quick snack and the writer went to the watertruck to replenish his waterbottle (the daily ration, which was to be used for drinking as well as any other purpose such as washing and shaving, was supposed to last the whole day). He then showed a few samples of the Italian banknotes to the more knowledgeable paymaster. His reaction was immediate - he said 'Sgt Centner, this stuff is completely valueless as a currency in East Africa.'

As a result, the writer removed all the bundles from his already overfull kitbag and, after retaining an example of each denomination as a souvenir, threw the lot into the nearest bush. On reaching Addis Ababa, he learned that the Italian currency was fixed at something like L400 to the pound sterling!

S/Sgt Mannie Centner in 1942.

Tired after the long drive, the writer sat in the cab of his truck. Rain was coming down in buckets - it was the rainy season in Abyssinia - when he suddenly saw a naked man, then another, streaking through the campsite. A while later, he was ordered by an officer to take three 'sick' men to the nearest field medic for immediate treatment. With a co-driver and three 'bodies' in the back, the writer made urgent enquiries from various units parked on either side of the road and eventually received directions to a tent with a Red Cross sign. A medic appeared in the flap, looked at the three bodies and exclaimed 'Some more cases of aniseed poisoning!' Those three men never rejoined the unit.

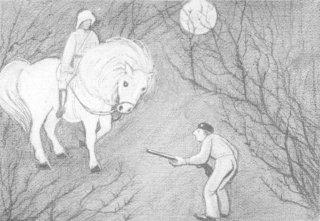

One black, hot and apparently endless night, while on guard duty and walking around the perimeter of the camp, trying to keep awake until daybreak, plodding through soft sand, careful not to stray in the wrong direction, getting lost in the bush with his rifle on his shoulder, the writer suddenly saw something very large and ghostly white approaching. With his heart in his mouth he shouted 'Who goes there?' Upon closer inspection, he realised that the apparition was a white man with a white helmet astride a beautiful white horse.

Sketch by Mannie Centner of his encounter with the

'White Ghost' of Arbo Wells, October 1942.

'This is Colonel Orde Wingate of the British Army and I want to see your commanding officer immediately' he said. 'Wait here, Sir' the writer told him and found his commanding officer, Major 'Plumber' Clark asleep in his tent. 'Oh' he said, 'He must be the chap trying to organise the Abyssinian irregulars into a regular unit to help us round up the thousands of Italian deserters in the bush - bring him in.'

It was many years later that the writer read the story of Colonel Wingate. He had previously been in Palestine, organising Arab irregulars, then he escorted Emperor Haile Selassi back to Addis Ababa. He became famous in Burma with the 'Chindits' and is remembered as 'General Lord Wingate of Burma'.

After months of chasing the Italian East African Army through central and western Abyssinia, the discipline in the 1st Light Tank Company was relaxed and almost non-existant. The daily parades at sunrise and sunset were abandoned, as was the custom of saluting all superior officers. It was impossible to keep clean in and out of the tanks and trucks, occasionally knee deep in the mud in the lake regions of Abyssinia during the rainy season. As a result, all of them, officers and men, looked filthy and resembled a bunch of disreputable hoboes.

Also in the brigade were some Gold Coast (Ghana) infantry and an Indian battery of small field guns mounted on the back of mules, the barrel carried by one mule and the two wheels slung over the back at each side of another. The battery consisted of the Indian Army's regulars, Sikhs and Ghurkas. One afternoon, the writer and his half section buddy walked across from their campsite to that of the Indian Mountain Battery. There they were confronted by a sight so amazing that it seemed to be miraculous; the Sikhs and Ghurkas were on their usual sunset parade, rows of immaculately clean soldiers, their turbans pure white, their boots and belts highly polished in a clearing in the muddy bush. In comparison to those professionals, the South Africans were mere volunteers and amateurs.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page