The South African

The South African

by Ian B Copley

Foreward

A large highway is planned to cross the Magaliesberg at a pass known as Silkaatsnek. The planners have chosen to use not the western side of the central kopje (where a modern road and three earlier roads cross over side by side), but the eastern side, thus destroying the unspoilt part of the Nek. It is the eastern side of the Nek which carries a partially visible pre-Boer War wagon road, taking the easier, but slightly longer route towards Rustenburg. It was also here that the two 12-pounder guns of 'O' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), were placed and ultimately captured in the first battle of Silkaatsnek (11 July 1900)(1) and there is an open spring site in an intermediate position between the bushveld of the northern slopes and the grassland of the southern Magaliesberg, which was repeatedly occupied by Early Stone Age people.(2) All of this will be obliterated by the new road which will complete the destruction already caused by clay-pit mining, a century of roadworks, electricity pylons and indiscriminate bulldozing for a dam and drainage furrows.

The British attack on the Boers occupying the Nek described below took place mainly on the eastern side, whereas the Boers used both sides of the Nek in the one day siege of the kopje during the first battle of Silkaatsnek.

Introduction

In the campaign to control the Western Transvaal after the disasters of Silkaatsnek, Onderstepoort and Dwarsvlei

on 11 July 1900, Lord Roberts had come to the conclusion that remote, isolated posts (such as Rustenburg and

Oliphant's Nek), which were in constant danger of attack and capture, should be evacuated. (Eventually, the forces

withdrawn from the west would be used to garrison Commando Nek and Silkaatsnek).

For several weeks, Colonel Hore had kept a small garrison of Australians at Brakfontein, 40 miles (64 km) further west.(3) He had been maintaining communications with Mafeking and Zeerust, policing the district and helping to forward convoys to Rustenburg.(4) At the time, for the purpose of guarding a large quantity of supplies, he had some 500 men, mostly Imperial Bushmen or Rhodesians, who had with them an old 7-pounder muzzle- loading screw-gun and two Maxims of .303 and .450 calibre.

Attempts were soon being made to relieve Hore. On 1 August 1900, Roberts ordered General Carrington, who had come down from Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) to Mafeking, to march to Elands River to cover Hore's retirement through the Magaliesberg to Rustenburg. By 2 August, Carrington's force had absorbed Colonel the Earl of Errol's small force at Otto's Hoop and had reached Zeerust, 71 km out of Mafeking. He was unaware that Hore was already besieged when he set off.(5)

General De la Rey's three detachments, comprising 300 troops each (under himself and Commandants Lemmer and Steenkamp) and each equipped with a gun, a pom-pom, and a Maxim, were on their way to forestall Carrington and arrived at Elands River before him. In addition, De la Rey had forces positioned at Commando Nek and Silkaatsnek, effectively cutting off Rustenburg from Pretoria.(6)

General Ian Hamilton, who had recently returned from the Eastern Railway Line with Mahon's and Cunning- ham's brigades, was directed to march into the disturbed Rustenburg district and bring Baden-Powell's forces back to Pretoria.(7)

The Battle

On 1 August 1900, General Hamilton moved his main force out of Pretoria along the road to Rustenburg. Col

T E Hickman's Mounted Infantry (MI) went ahead as advance guard.(8) The road ran in the Moot or valley to

the south of the Magaliesberg, parallel to the cliffs 3 to 5 km distant, which rose some 300 to 400 metres above

the road. Approximately 20 km from Pretoria the road forked, the right-hand road heading directly towards the

pass of Silkaatsnek, which could be seen clearly as a U-shaped gap with a small, rocky kopje dividing the pass

into a right and left half.

The other road continued to the wooden Paul Kruger Bridge over the Crocodile River on General Hendrik Schoeman's farm, thence over Commando Nek to join the Rustenburg road from Pretoria via Wonderboom, Horns Nek or Silkaatsnek.

Brig-Gen B T Mahon's Cavalry and Mounted Infantry Brigade followed the gentler slopes on the northern side through thick bushveld, in contrast to the grasslands to the south. Boers on top of the range were able to fire in a desultory fashion at the two bodies of troops moving in a westerly direction on either side of them.(9) (Both Commando Nek and Silkaatsneka had been in the hands of the Boers following the first battle of Silkaatsnek on 11 July 1900).(10)

Hamilton's force of 7 600 men comprised the mounted forces of Brig-Gen Mahon and Col Hickman, and Brig- Gen G C Cunningham's infantry, supported by the 75th Battery Royal Field Artillery (RFA), the Elswick Battery, and two companies of Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA).(b) Cunningham's force was made up of four strong infantry battalions: 1st King's Own Scottish Borderers, 1st Border Regiment, 1st Argyll and Sutherland High- landers, 2nd Royal Berkshire Regiment, and 'S' Section, Vickers Maxims.

Hickman's MI was a rather mixed selection, including details from the 2nd Brigade MI, released prisoners, convalescents from all irregular horse units in South Africa (formed into two complete regiments under Major S B von Donop and Lt-Col A N Rockfort RA), the 3rd Queensland Imperial Bushmen, and one Vickers Maxim section (added later) - a total of 1 500 men.

Mahon's force comprised 'M' Battery Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), the Imperial Light Horse, Lumsden's Horse, a battalion of Imperial Yeomanry, 3rd Corps of Mounted Infantry, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, detachments of Queenslanders, Bushmen, and 18th Hussars - a total of 1 700 mounted men.

Communication between the two columns was not very good since there were no troops on the summit of the Magaliesberg. Thinking that Mahon might be in difficulty (he was slowed down by thick bush and sniping), Hamilton considered it necessary to break through the mountains at Silkaatsnek, the second pass suitable for wheeled traffic west of Pretoria, in order to keep in touch with his northern force. Intelligence information suggested that the pass was held by a diminished garrison of 300 to 400 Boers under Cmdt Coetzee, acting under the orders of General De la Rey, and that they had no guns in the Nek. The main body of the enemy was believed to be 1 500 strong with four guns near the Sterkstroom River, 25 miles (40 km) northwest.(11) The British main force, having travelled along the Moot, was in a position to attack the Nek during the early morning of 2 August 1900. Hamilton entrusted the attack to Cunningham's brigade. The Royal Berkshire Regiment and the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders were to attack the pass and attempt to drive its defenders onto Mahon's force. (12) However, as Hamilton believed Mahon to be in difficulty, he decided to attack at once to relieve pressure on him.

Silkaatsnek is a U-shaped gap in the Magaliesberg Range, affording easy passage to wheeled transport. At this point, the Magaliesberg rises some 1 300 ft (396 m) above the plain, whilst the ascent over the Nek is a mere 350 ft (107 metres). The Nek is divided into two halves by an elongated rocky outcrop or kopje and the old Boer War road over the Nek takes the western (left) side of the kopje. At the top of the slope, this road passes through a cutting in the Nek for 20 to 25 yards (13 metres) next to the kopje.

The kopje overlooks the pass on either side by some 75 ft (23 metres), but is itself overlooked by the shoulders of the mountains on either side, which rise another 950 ft (290 metres) steeply on the eastern side, but more gradually and step-wise to the west. The western buttress is almost completely separated from the main range by a deep gully in the northern slope.

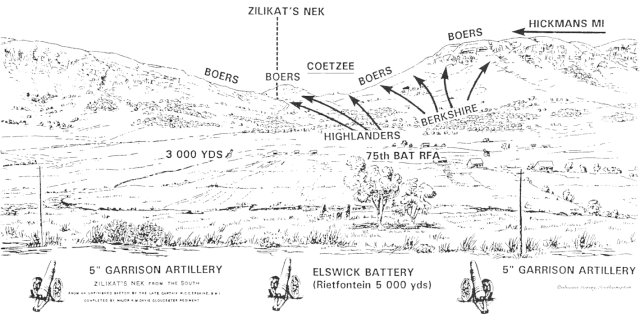

Panoramic view of Silkaatsnek from the high ground at Rietfontein Camp looking north.

Note the telegraph poles for the Pretoria-Rustenburg line next to the road.

The northern aspect of the range has a fairly constant slope produced by the tilt of quartzite rock beds. Apart from gulleys and ravines caused by the erosion of dykes and sills, an ascent can be made almost anywhere. By contrast, the southern aspect has a sheer cliff face and can be climbed only in a few places on foot, and occasionally on horseback. During the Boer War, the northern slopes and gulleys were covered in thick bush, whilst the southern side supported a more open savannah, except at the base of the cliffs and, in the case of Silkaatsnek, along the course of the stream, where the bush was much thicker, with a belt of 'mimosa trees half a mile broad.'(13)

It was this pass that Cunningham was ordered to force with his brigade and a field battery. The Berkshires were detailed for the right attack with the high eastern buttress facing them. The intervening mile or so of mimosa (acacia) trees, being leafless in winter, provided scant cover from the enemy on the heights. The Highlanders took the left side, facing the eastern part of the pass and the central kopje.

'A' and 'B' Companies of the Berkshires, commanded by Maj McCracken, were in the firing line, with 'C' and 'D' in support, and 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', and Volunteer Companies in the second line. Initially, the advance was straight up against the foot of the eastern buttress, but this position was found to be so strongly held that it became necessary to incline to the right and clear that side of the pass before entering it. The ground open to frontal attack was limited and a turning manoeuvre was difficult.

The left flank of the Highlanders was kept back at first, on account of the very exposed nature of the ground, whilst the companies on the right pushed rapidly forward under the cover of dongas and scrub to within 100 yards (91 m) of the pass (ie up the bed of the stream arising from the eastern side of the pass which supported much denser vegetation). The attack was gallantly carried out by 'A' and 'C' Companies of the Berkshires under very heavy fire.(14)

The 75th Battery RFA shelled the enemy from a position 3 000 yards (2 700 metres) to the south, half-way across the valley floor, assisted by the Elswick Battery in the centre and the 5-inch guns of the Garrison Artillery from the rear, probably from the vantage point of one of the four hills already partly fortified next to the main road at Rietfontein. (15) The gunners were firing at groups of men visible on the cliffs on both sides of the Nek. The attack was also supported by strong fire from the infantry's three machine guns directed at either side of the pass. The artillery situation was almost exactly the same as in the first battle of Silkaatsnek, except that the range and fire power was much greater than before.

The Berkshires were thus able to advance under the cover of the steepest part of the eastern buttress, while the Highlanders worked through the thick bush on the left. Good progress was made until 09.15. Hamilton, seeing that the heights had not yet been gained, kept back the remainder of Cunningham's force. By 10.30, a party of fifty of Hickman's Mounted Infantry, who had been sent to a gap 3 miles (5 km) east of the Nek, where it appeared possible to scale the cliffs and assist in the attack, reached the summit. They proceeded unopposed along the top.(16) (This unnamed gap now carries a power line). A small reconnoitring party, which had been sent up the evening before, had suffered six casualties.(17)

Half an hour later, at 11.00, the two front line companies of the Berkshires managed to climb the steep cliffs on the eastern buttress under a heavy crossfire. Sgt A Gibbs had gone to reconnoitre and was shot as he reached the top. Pte House then rushed out from cover (despite being cautioned not to do so as the enemy fire was very intense), picked up the wounded sergeant and endeavoured to bring him into shelter. In doing so, he was himself severely wounded. However, he warned his comrades not to come to his assistance, the fire being so severe.(c)

The objective referred to as a 'kopje' in the regimental records actually resembled a solitary conical hill when the eastern buttress of the Nek is viewed from below, the rest of the Magaliesberg Range being obscured. The ground rose steeply, at an angle of almost 45 degrees beneath the cliffs. The only possible route to the summit from the south side was via a narrow gully between the vertical cliffs. (To work to the left would be to expose the left flank to Boer fire from the kopje and the opposite side of the Nek). However, there was an open area between the comparative shelter of the trees and the base of the cliffs, which the front line would have had to cross, under covering fire from the supporting companies and machine guns, to gain the final access to the summit. From the foot of the gully, progress was probably made by leapfrogging cover, which would have been least effective at the point where the gully opens at the near-summit. This is almost certainly where Pte House gained his Victoria Cross (VC).

After the occupation of the eastern heights, the centre resumed its advance. In doing so, they passed the recent graves of the Lincolnshires, Scots Greys and Royal Horse Artillery on the left at the foot of the Nek.(d) Despite their strong position, the Boers under Coetzee were forced back, offering little resistance, and they were in full flight before midday.(18) The pass was rushed and occupied by the Highlanders under Captain H McDonald.(19) They captured a number of horses and wagons.

Meanwhile Mahon, delayed by bad terrain, enemy attacks, and the fact that the day's orders heliographed from Hamilton were not received until 09.15, did not reach the north side of the pass in time to intercept any of the fleeing Boers. He was still 5 miles (8 km) away at the end of the engagement.(20) Seventeen Boer prisoners were taken.(21) Casualties on their side were estimated at a dozen killed and several wounded Boers were found on neighbouring farms.(22) The Berkshires suffered by far the heaviest casualties on the British side, as their right flank had been on very high and exposed ground. One sergeant and three (should be four) privates were reported killed, and Lt-Col E Rhodes, DSO, Maj G D R Williams and three other ranks were wounded. The Highlanders had one killed and three wounded.(23) Wounds were mostly of a serious nature as the Boer prisoners owned to the fact that they had had soft-nosed bullets served out to them and had used them.(24)

Commando Nek was found to be unoccupied.(25) Hickman's force with the 1st Bn King's Own Scottish Borderers and a section of the Elswick Battery were left to garrison Commando Nek.(26) After forcing Silkaatsnek, Hamilton continued westwards and effected a junction with General Baden-Powell at Kroondaal and continued unmolested into Rustenburg on S August 1900.(27)

A Divisional Order stated that the GOC Hamilton's Force 'has expressed his approval of the manner in which today's operations have been carried out, especially noting the admirable way in which the climbing of the kopje [sic] on the right was effected'.(28)

Discussion

The occupation of Silkaatsnek by the Boers after 11 July 1900 effectively cut off routes either north or south of the

Magaliesberg to the Western Transvaal and Rustenburg. Access was therefore limited to a long detour via

Krugersdorp.

Having seen some 7 000 troops and several guns advancing towards them front and rear, it would have been most unlikely that the Boers would have made a decisive stand. It is not beyond expectation that, had Mahon's progress been more expeditious, there might have been no second battle at Silkaatsnek. As Mahon, like the rest of the army, had been under observation along the length of the Magaliesberg ridge, it is unlikely that the Boers would have stayed on the Nek whilst they were being cut off from the rear. They apparently did not anticipate the final rush by the Highlanders and consequently forfeited some horses and wagons. Had they had two guns in the Nek facing southwards (as the Lincolns had had facing northwards during the first battle of Silkaatsnek), they could have done considerable damage to the troops in the valley below before the heights were occupied.

The British seemed to have learned from their experience of the earlier battle. Although they commenced a frontal attack from the south, due recognition of the importance of the heights was taken into consideration by sending Hickman's party along the crest towards the Nek. Had the party been stronger and arrived a little sooner, the Berkshires might not have had the same difficulties in gaining the eastern buttress. (A year later, three blockhouses were constructed at this site). In view of the skirmish with Hickman's troops the evening before, it is surprising that the Boers did not anticipate his advance along the ridge. His appearance above the Nek was a decisive factor in the Boer withdrawal.

Baden-Powell's fortified camp at Rietfontein had been abandoned by Col Alexander and the HQ Company of the Scots Greys after the first battle of Silkaatsnek on 11 July 1900. As noted by Hickman on 25 July, the Boers maint- ained a laager in the area of Silkaatsnek and Commando Nek and could have occupied the British camp for the same reasons that Baden-Powell had chosen this strategic position.(29) However, it may have been more practical for the Boers, who lacked sufficient long-range artillery, to remain closer to Commando Nek. Judging by the communique from General Hamilton (R 0 Reitfontein [sic] Camp SAR 2/8/1900), he had established his headquarters there and, as activity in and communications with the Western Transvaal increased, it is believed that the camp was continuously occupied by the British from 2 August 1900.

Notes

References

Bibliography

Amery, L S (ed), The Times History of the War in South Africa, Vol IV (Lampson LOW, London, 1906).

Creswicke, L, South Africa and the Transvaal War, Vol VI (TC & EC Jack, Edinburgh, 1901).

Dunn-Pattison, R P, The History of the 91st Argyllshire Highlanders (Blackwood, London, 1910).

Goldmann, C S, With General French and the Cavalry in South Africa, (Macmillan, London, 1902).

Lee, A, History of the Tenth Foot (Gale & Polden, London, 1911).

Maurice, Sir F (ed), History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, (H M Govt, London, Hurst & Blackett, 1908).

Regimental Diary: 2 Royal Berkshire Regiment (Salisbury).

Robertson, I (ed), Cavalry Doctor, (Robertson, Constantia, 1975).

Wilson, H W, With the Flag to Pretoria, Vol III (Harmsworth, London, 1901).

Wulfsohn, L, Rustenburg at War (Wulfsohn, Rustenburg, 1992).

Acknowledgements and thanks are due to:

Audio-Visual Department, Medunsa.

Maj P J Ball, Regimental Museum, Duke of Edinburgh's Royal Regiment (Berkshire & Wiltshire) Salisbury England.

Prof C J Barnard, South African Military History Society

Miss J Beater, British War Graves Division, SA National Monuments Council.

Mrs I B Copley, South African Military History Society.

Mrs J Lochner, Dept of Neurosurgery, Medunsa.

Lt-Col A W Scott Elliot, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, Stirling Castle, Scotland.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page